Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(8):2453-2462

Swallowing disorders are common, especially in the elderly, and may cause dehydration, weight loss, aspiration pneumonia and airway obstruction. These disorders may affect the oral preparatory, oral propulsive, pharyngeal and/or esophageal phases of swallowing. Impaired swallowing, or dysphagia, may occur because of a wide variety of structural or functional conditions, including stroke, cancer, neurologic disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease. A thorough history and a careful physical examination are important in the diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders. The physical examination should include the neck, mouth, oropharynx and larynx, and a neurologic examination should also be performed. Supplemental studies are usually required. A videofluorographic swallowing study is particularly useful for identifying the pathophysiology of a swallowing disorder and for empirically testing therapeutic and compensatory techniques. Manometry and endoscopy may also be necessary. Disorders of oral and pharyngeal swallowing are usually amenable to rehabilitative measures, which may include dietary modification and training in specific swallowing techniques. Surgery is rarely indicated. In patients with severe disorders, it may be necessary to bypass the oral cavity and pharynx entirely and provide enteral or parenteral nutrition

Impaired swallowing, or dysphagia, can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Swallowing disorders are especially common in the elderly. The consequences of dysphagia include dehydration, starvation, aspiration pneumonia and airway obstruction.1,2 Dysphagia may result from or complicate disorders such as stroke, Parkinson's disease and cancer. Indeed, aspiration pneumonia is a common cause of death in hospitalized patients. This article reviews the basic concepts of normal and abnormal swallowing, methods of evaluating dysphagia, and treatment strategies, with emphasis on disorders of oral and pharyngeal swallowing.

Physiology

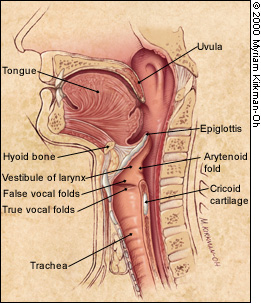

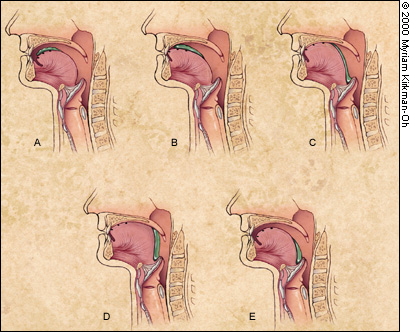

The oral preparatory phase refers to the processing of the bolus to render it “swallowable,” and the oral propulsive phase refers to the propelling of food from the oral cavity into the oropharynx4,5 (Figure 2). With single swallows of liquid, the pharyngeal phase follows immediately. For swallows of solid foods, there may be a delay of five or 10 seconds while the bolus accumulates in the oropharynx.4

Whatever the food consistency, the pharyngeal phase involves a rapid sequence of overlapping events. The soft palate elevates. The hyoid bone and larynx move upward and forward. The vocal folds move to the midline, and the epiglottis folds backward to protect the airway. The tongue pushes backward and downward into the pharynx to propel the bolus down. It is assisted by the pharyngeal walls, which move inward with a progressive wave of contraction from top to bottom. The upper esophageal sphincter relaxes during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing and is pulled open by the forward movement of the hyoid bone and larynx.3 This sphincter closes after passage of the food, and the pharyngeal structures then return to reference position (Figure 3).

In the esophageal phase, the bolus is moved downward by a peristaltic wave. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and allows propulsion of the bolus into the stomach. Unlike the upper esophageal sphincter, the lower sphincter is not pulled open by extrinsic musculature. Rather, it closes after the bolus enters the stomach, thereby preventing gastroesophageal reflux.

Disorders of Swallowing

Disorders of swallowing may be categorized according to the swallowing phase that is affected. Impairments of the oral and pharyngeal phases are sometimes termed “transfer” dysphagias.

ORAL PHASES

Disorders affecting the oral preparatory and oral propulsive phases usually result from impaired control of the tongue,7 although dental problems may also be involved. When eating solid food, patients may have difficulty chewing and initiating swallows. When drinking a liquid, patients may find it difficult to contain the liquid in the oral cavity before they swallow. As a result, liquid spills prematurely into the unprepared pharynx, and this often results in aspiration.

PHARYNGEAL PHASE

With dysfunction of the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, food transport to the esophagus may be impaired. As a result, food is retained in the pharynx after a swallow.

In normal persons, small amounts of food are commonly retained in the valleculae or pyri-form sinus after swallowing.5 With obstruction of the pharynx by a stricture, web or tumor, weakness or incoordination of the pharyngeal muscles, or poor opening of the upper esophageal spincter,8 patients may retain excessive amounts of food in the pharynx and experience overflow aspiration after swallowing.7 If pharyngeal clearance is severely impaired, patients may be unable to ingest sufficient amounts of food and drink to sustain life.

A pharyngeal diverticulum may also impair pharyngeal emptying by diverting the bolus from its normal course. In addition, weakness of the soft palate and pharynx may lead to the nasal regurgitation of food.

ESOPHAGEAL PHASE

Impaired esophageal function can result in the retention of food and liquid in the esophagus after swallowing.9 This retention may result from mechanical obstruction, a motility disorder or impaired opening of the lower esophageal sphincter.

The body of the esophagus may be obstructed by a web, stricture or tumor. Esophageal propulsive forces may be reduced because of weakness or incoordination of esophageal musculature. Overactivity of the esophageal musculature may result in esophageal spasm, which also reduces the effectiveness of esophageal food transport.

Although not a swallowing disorder per se, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a closely related problem.9 Patients with GERD are at risk for reflux esophagitis. They are also at risk for peptic strictures, which may obstruct the esophagus and result in dysphagia.

ASPIRATION

Aspiration is the passage of food or liquid through the vocal folds.7 Persons who aspirate are at increased risk for the occurrence of serious respiratory sequelae, including airway obstruction and aspiration pneumonia.10–13 Aspiration is often caused by impaired laryngeal closure, but it may also occur because of the overflow of food or liquids retained in the pharynx.

The effects of aspiration are highly variable.11,12 Normal persons routinely aspirate microscopic amounts of food and liquid. Gross aspiration is abnormal and may lead to respiratory complications. However, some persons tolerate aspiration better than others. Several factors influence the effects of aspiration:

Quantity. Aspirating larger quantities is riskier.

Depth. Aspirating material into the distal airways is more dangerous than aspirating material into the trachea.

Physical properties of the aspirate. Solid food may cause fatal airway obstruction. Acidic material is dangerous because the lungs are highly sensitive to the caustic effects of acid. Aspirating refluxed acidic stomach contents may cause serious damage to the pulmonary parenchyma. Aspirating material laden with infectious organisms or even normal mouth flora can cause bacterial pneumonitis.

Pulmonary clearance mechanisms. These mechanisms include ciliary action and coughing. Aspiration normally provokes a strong reflex cough. If sensation is impaired, “silent aspiration” (without cough or throat clearing) may occur.14 Silent aspiration is likely to cause respiratory sequelae, as is aspiration in persons with an ineffective cough or impaired level of consciousness.

Evaluation

HISTORY

The first objective in evaluating dysphagia is to recognize the problem, because some patients are not consciously aware of their difficulty with swallowing (e.g., those with silent aspiration). The second objective is to identify the anatomic region involved: Is the problem oral, pharyngeal or esophageal?

The third objective is to acquire clues to the etiology of the condition. This includes information about the onset, duration and severity of the swallowing problem, the presence of regurgitation, the perceived level of obstruction and the presence of pain or hoarseness. A knowledge of the presence of other disorders, such as dental problems, cervical spondylosis or a history of wheezing, may also be helpful in determining the cause of dysphagia.

Swallowing disorders may present with a number of signs and symptoms (Table 1). Some of these presentations can be quite subtle.

| Oral or pharyngeal dysphagia |

| Coughing or choking with swallowing |

| Difficulty initiating swallowing |

| Food sticking in the throat |

| Drooling |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| Change in dietary habits |

| Recurrent pneumonia |

| Change in voice or speech |

| Nasal regurgitation |

| Esophageal dysphagia |

| Sensation of food sticking in the chest |

| Oral or pharyngeal regurgitation |

| Food sticking in the throat |

| Drooling |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| Change in dietary habits |

| Recurrent pneumonia |

Oral or pharyngeal dysphagia may be caused by a wide variety of conditions (Table 2).15 Because their effects are quite similar, these conditions usually cannot be differentiated by analysis of the history, although other clues may be helpful. For example, concomitant complaints of limb weakness suggest the presence of neurologic or connective tissue disease.

| Neurologic disorders and stroke |

| Cerebral infarction |

| Brain-stem infarction |

| Intracranial hemorrhage |

| Parkinson's disease |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Poliomyelitis |

| Myasthenia gravis |

| Dementias |

| Structural lesions |

| Thyromegaly |

| Cervical hyperostosis |

| Congenital web |

| Zenker's diverticulum |

| Ingestion of caustic material |

| Neoplasm |

| Psychiatric disorder |

| Psychogenic dysphagia |

| Connective tissue diseases |

| Polymyositis |

| Muscular dystrophy |

| Iatrogenic causes |

| Surgical resection |

| Radiation fibrosis |

| Medications |

Radiologic and laboratory studies are usually necessary to diagnose oral or pharyngeal dysphagia. The history is often more useful in identifying esophageal dysphagia. For example, the complaint of food sticking or stopping in the chest is highly suggestive of an esophageal disorder. If esophageal dysphagia is suspected, the cause can often be determined based on the history and confirmed with appropriate diagnostic studies (Figure 4).15

The history should also be directed at eliciting symptoms related to GERD, including heartburn, belching and sour regurgitation. The patient's current medications should be reviewed because some drugs, especially psychotropic medications, can exacerbate dysphagia (Table 3).

| Oropharyngeal function | |

| Sedation, pharyngeal weakness, dystonia | |

| Benzodiazepines | |

| Neuroleptics | |

| Anticonvulsants* | |

| Myopathy | |

| Corticosteroids | |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | |

| Xerostomia | |

| Anticholinergics | |

| Antihypertensives* | |

| Antihistamines* | |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Narcotics | |

| Anticonvulsants* | |

| Antiparkinsonian agents* | |

| Antineoplastics* | |

| Antidepressants* | |

| Anxiolytics* | |

| Muscle relaxants* | |

| Diuretics | |

| Inflammation/swelling | |

| Antibiotics* | |

| Esophageal function | |

| Inflammation (resulting from irritation by pill) | |

| Tetracycline | |

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin) | |

| Iron preparations | |

| Quinidine | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Potassium | |

| Impaired motility or exacerbated gastroesophageal reflux | |

| Anticholinergics | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Theophylline | |

| Esophagitis (related to immunosuppression) | |

| Corticosteroids | |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

During the physical examination, it is important to look for evidence of neurologic, respiratory and connective tissue disorders that may affect swallowing. To this end, an examination of oral-motor and laryngeal mechanisms is critical.

The anterior neck is inspected and palpated for masses. Dysphonia (abnormal voice) and dysarthria (abnormal speech articulation) are signs of motor dysfunction of the structures involved in oral and pharyngeal swallowing. The thyroid cartilage is gently mobilized by manual distraction to either side. Laryngeal elevation is evaluated by placing two fingers on the larynx and assessing movement during a volitional swallow.

The oral cavity and pharynx are inspected for mucosal integrity, masses and dentition. The soft palate is examined for position and symmetry during phonation and at rest.

The gag reflex is elicited by stroking the pharyngeal mucosa with a cotton-tipped applicator or tongue depressor. A gag reflex can be elicited in most normal persons. However, absence of a gag reflex does not necessarily indicate that a patient is unable to swallow safely. Indeed, many persons with an absent gag reflex have normal swallowing, and some patients with dysphagia have a normal gag reflex. The pulling of the palate to one side during gag reflex testing indicates weakness of the muscles of the contralateral palate and suggests the presence of unilateral brain-stem (bulbar) pathology.

The patient should also be observed during the act of swallowing. At a minimum, the patient should be watched while he or she drinks a few ounces of tap water. In normal persons, swallowing is initiated promptly, and no significant amount of material is retained after a swallow. Drooling, delayed swallow initiation, coughing, throat clearing or a change in voice quality may indicate a problem. After the swallow, the patient should be observed for a minute or more to see if there is a delayed cough response.

One study showed that a water swallow test in patients who had a stroke identified 80 percent of those subsequently found to be aspirating based on radiographic studies.16 Family physicians can use the water swallow test to identify patients who need to be referred for further evaluation.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

The videofluorographic swallowing study (VFSS)* is the gold standard for evaluating the mechanism of swallowing.17,18 For this study, the patient is seated comfortably and given foods mixed with barium to make them radiopaque. The patient eats and drinks these foods while radiographic images are observed on a video monitor and recorded on videotape. Ideally, the VFSS is performed jointly by a physician (typically a radiologist or physiatrist) and a speech-language pathologist. *— The videofluorographic swallowing study is similar to the modified barium swallow, except that the protocol for the modified barium swallow specifies quite small bolus volumes and does not include drinking from a cup. In practice, the terms “videofluorographic swallowing study” and “modified barium swallow” are often used interchangeably.

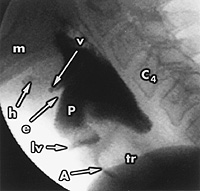

The VFSS demonstrates anatomic structures, the motions of these structures and the passage of the barium-food bolus through the oral cavity, pharynx and esophagus (Figure 5). If aspiration occurs or food is retained after swallowing, the next step is to evaluate the quantity of retained food, the mechanism of retention or aspiration, and the patient's response (e.g., coughing, choking or discomfort).

By testing various foods, it is possible to determine the effects of food consistency on swallowing. For example, some, but not all, patients with poor bolus control experience less aspiration with thick liquids (e.g., apricot nectar or tomato juice) than with thin liquids (e.g., water or apple juice). Patients with poor pharyngeal contraction usually have more pharyngeal retention with thickened liquids and chewed solid foods than with thin liquids. The results of the VFSS make it possible to design an individualized diet. This diet would include foods that could be eaten and swallowed safely by a particular patient.1,19

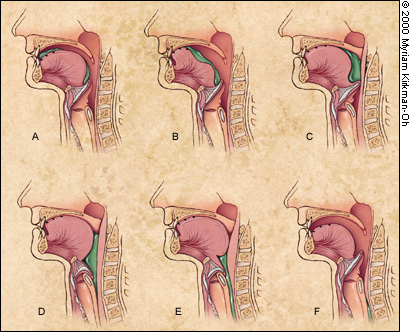

With the VFSS, it is also possible to test the effectiveness of compensatory maneuvers designed to improve pharyngeal clearance or reduce aspiration. For example, tucking the chin (neck flexion) or holding the breath before swallowing may reduce aspiration. Turning the head toward the weak side may improve pharyngeal clearance by deflecting the bolus to the strong side in a patient with unilateral pharyngeal weakness.20,21

Other maneuvers have been developed to improve opening of the upper esophageal sphincter, increasing pharyngeal clearance and minimizing aspiration. These techniques include altering the position of the head, neck and body relative to gravity, modifying the method of feeding or teaching the patient to voluntarily contract particular muscles during the act of swallowing. The effectiveness of these maneuvers may be tested during fluoroscopy.1,19–21

ADDITIONAL DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Esophagoscopy can be used to rule out neoplasia in patients who complain of thoracic dysphagia or odynophagia (pain on swallowing).9 Esophageal manometry and pH probe studies may be appropriate when a motility disorder or GERD is suspected, but they are rarely the first lines of investigation. Electromyography is indicated in patients with motor unit disorders, such as polymyositis, myasthenia gravis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.22

In the fiberoptic endoscopic examination of swallowing (FEES), a transnasal laryngoscope is used to assess pharyngeal swallowing.23 Because pharyngeal contraction obstructs the lumen, the FEES does not show the motion of essential foodway structures or the food bolus during the swallow. However, it can identify aspiration and pharyngeal retention after the swallow. A FEES may be helpful when a VFSS is not feasible.

Treatment Principles

The goals of dysphagia therapy are to reduce aspiration, improve the ability to eat and swallow, and optimize nutritional status. Principal treatments for selected disorders that affect swallowing are listed in Table 4.

| Disorders | Treatments |

|---|---|

| Stroke, multiple sclerosis | Dietary modification, compensatory maneuvers, swallow therapy |

| Wallenberg's syndrome (lateral medullary infarction) | Turning head toward side of infarction, dietary modification, swallow therapy |

| Peptic stricture of the esophagus, achalasia of the lower esophageal sphincter | Dilatation |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | Dietary modification, no eating at bedtime, remaining upright after eating, pharmacologic therapy, smoking cessation |

| Diffuse esophageal spasm | Pharmacologic therapy |

| Parkinson's disease, polymyositis, myasthenia gravis | Pharmacologic therapy for the underlying disease (dietary modification, compensatory maneuvers and swallow therapy only if necessary) |

| Esophageal cancer | Esophagectomy |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Dietary modification, compensatory maneuvers, counseling and advance directives |

When possible, treatment is directed at the underlying disorder, such as Parkinson's disease or polymyositis. However, many of the disorders that cause dysphagia, such as stroke or progressive bulbar palsy, are not amenable to pharmacologic therapy. In these situations, therapy is individualized based on the functional and structural abnormalities and the initial responses to treatment trials observed at the patient's bedside or during a VFSS.

A basic principle of rehabilitation is that the best therapy for any impaired activity is the activity itself. For instance, walking is generally the best exercise to improve ambulation skills. Similarly, swallowing is generally the best therapy for swallowing disorders. Thus, the pretreatment evaluation is directed at identifying circumstances for safe and effective swallowing in the individual patient.

DIETARY MODIFICATION

Dietary modification is a common treatment approach. As mentioned previously, patients vary in their ability to swallow thin and thick liquids.24 A patient can usually receive adequate oral hydration with thin or thick liquids. Rarely, a patient may be limited to foods with a pudding consistency if thin and thick liquids are freely aspirated.

Most patients with significant dysphagia are unable to eat meats or similarly tough foods safely. Hence, they require a mechanical soft diet. A pureed diet is recommended for patients who exhibit difficulties with the oral preparatory phase of swallowing, who “pocket” food in the buccal recesses (between the teeth and cheek) or who have significant pharyngeal retention of chewed solid foods.

SWALLOW THERAPY

Swallow therapy, another common form of rehabilitation, can be divided into three types: compensatory techniques (i.e., postural maneuvers), indirect therapy (exercises to strengthen swallowing muscles) and direct therapy (exercises to perform while swallowing). Maintaining oral feeding often requires compensatory techniques to reduce aspiration or improve pharyngeal clearance.1,19

OTHER TREATMENTS

Surgery is rarely indicated in patients with oral or pharyngeal dysphagia, but it can be effective in selected patients. The most common surgical procedure for dysphagia is cricopharyngeal myotomy. In this procedure, the cricopharyngeus muscle is disrupted to reduce resistance of the pharyngeal outflow tract.8 This procedure is occasionally coupled with suspension of the thyroid cartilage, which is performed to improve laryngeal elevation. The specific indications and contraindications for these procedures remain unclear.

Enteral feeding is not always required in patients who aspirate. With a modified diet and use of compensatory maneuvers, most patients with minimal aspiration can learn to take sufficient food and drink by mouth to meet nutritional requirements. Patients with impaired level of consciousness, massive aspiration, silent aspiration, esophageal obstruction or recurrent respiratory infections often require enteral feeding.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy is commonly used for long-term enteral nutrition. However, this approach is itself associated with increased risks of gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration pneumonia.25 Parenteral feeding is expensive, but it may be medically appropriate in patients who develop aspiration pneumonia on tube feedings.