Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(12):3639-3648

Dysphagia is a problem that commonly affects patients cared for by family physicians in the office, as hospital inpatients and as nursing home residents. Familiar medical problems, including cerebrovascular accidents, gastroesophageal reflux disease and medication-related side effects, often lead to complaints of dysphagia. Stroke patients are at particular risk of aspiration because of dysphagia. Classifying dysphagia as oropharyngeal, esophageal and obstructive, or neuromuscular symptom complexes leads to a successful diagnosis in 80 to 85 percent of patients. Based on the patient history and physical examination, barium esophagram and/or gastroesophageal endoscopy can confirm the diagnosis. Special studies and consultation with subspecialists can confirm difficult diagnoses and help guide treatment strategies.

Complaints of dysphagia (difficult swallowing) are common, especially in aging persons. Approximately 7 to 10 percent of adults older than 50 years have dysphagia, although this number may be artificially low because many patients with this problem may never seek medical care.1,2 Up to 25 percent of hospitalized patients and 30 to 40 percent of patients in nursing homes experience swallowing problems.3,4

Epidemiology

Diseases of the esophagus are among the top 50 reasons that patients seek medical care and, in frequency, rank alongside problems such as pneumonia, bronchitis and otitis media.5 Conditions that cause dysphagia can produce esophageal rupture, nutritional deficits and aspiration pneumonia. Elderly patients are at the highest risk of dysphagia and its subsequent complications, especially silent aspiration.

Although the two conditions are often associated, dysphagia should be distinguished from odynophagia (painful swallowing). In addition, care should also be taken not to confuse globus with dysphagia. Globus is the constant sensation of a lump in the throat, although no organic defect or true difficulty in swallowing is apparent.

Anatomy and Physiology of Deglutition

Deglutition is the act of swallowing in which a food or liquid bolus is transported from the mouth through the pharynx and esophagus into the stomach. Normal deglutition involves a complex series of voluntary and involuntary neuromuscular contractions proceeding from the mouth to the stomach and is commonly divided into oropharyngeal and esophageal stages.

OROPHARYNGEAL STAGE

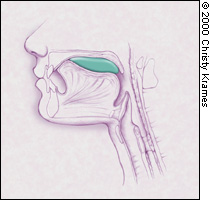

The oropharyngeal stage of deglutition begins with contractions of the tongue and striated muscles of mastication. The muscles work in a coordinated fashion to mix the food bolus with saliva and propel it from the anterior oral cavity into the oropharynyx, where the involuntary swallowing reflex is triggered6 (Figure 1a). The cerebellum controls output for the motor nuclei of cranial nerves V, VII and XII. The entire sequence lasts about one second.

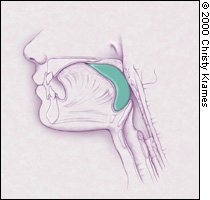

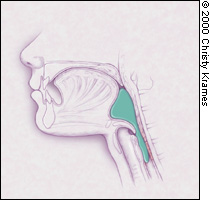

In the posterior oropharynx, a complex and precisely coordinated succession of muscular contractions and relaxations occurs. The soft palate elevates to close the nasopharynx, and the suprahyoid muscles pull the larynx up and forward6 (Figure 1b). The epiglottis moves downward to cover the airway while striated pharyngeal muscles contract to move the food bolus past the cricopharyngeus muscle (the physiologic upper esophageal sphincter and into the proximal esophagus6 (Figure 1c). This swallowing reflex lasts approximately one second and involves the motor and sensory tracts from cranial nerves IX and X.

ESOPHAGEAL STAGE

As food is propelled from the pharynx into the esophagus, involuntary contractions of the skeletal muscles of the upper esophagus force the bolus through the mid and distal esophagus. The medulla controls this involuntary swallowing reflex, although voluntary swallowing may be initiated by the cerebral cortex. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes at the initiation of the swallow, and this relaxation persists until the food bolus is propelled into the stomach. It may take eight to 20 seconds for the contractions to drive the bolus into the stomach.7

Pathophysiology

In oropharyngeal dysphagia, symptoms arise from the dysfunctional transfer of a food bolus in the pharynx past the upper esophageal sphincter into the esophagus. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is most common in elderly patients and frequently presents as part of a broader complex of signs and symptoms that lead the physician to a correct primary diagnosis. Stroke is the leading cause of oropharyngeal dysphagia.8

Esophageal dysphagia is caused by disordered peristaltic motility or conditions that obstruct the flow of a food bolus through the esophagus into the stomach. Achalasia and scleroderma are the leading motility disorders, while carcinomas, strictures and Schatzki's rings are the most common obstructive lesions.

History

Patients who have dysphagia may present with a variety of complaints, but they usually report coughing or choking, or the abnormal sensation of food sticking in the back of the throat or upper chest when they are trying to swallow. A carefully conducted patient history will enable the physician to identify 80 to 85 percent of the causes of dysphagia. Specific questions about the onset, duration and severity of the dysphagia, and a variety of associated symptoms (Table 2)9 may help narrow the differential diagnoses to a specific diagnosis or to an anatomic or pathophysiologic-related diagnosis.

| Condition | Diagnoses to consider | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive dysphagia | Neuromuscular dysphagia | ||

| Sudden dysphagia | Obstructive dysphagia, esophagitis | ||

| Difficulty initiating swallow | Oropharyngeal dysphagia | ||

| Food “sticks” after swallow | Esophageal dysphagia | ||

| Cough | |||

| Early in swallow | Neuromuscular dysphagia | ||

| Late in swallow | Obstructive dysphagia | ||

| Weight loss | |||

| In the elderly | Carcinoma | ||

| With regurgitation | Achalasia | ||

| Progressive symptoms | |||

| Heartburn | Peptic stricture, scleroderma | ||

| Intermittent symptoms | Rings and webs, diffuse esophageal spasm, nutcracker esophagus | ||

| Pain with dysphagia | Esophagitis | ||

| Postradiation | |||

| Infectious: herpes simplex virus, monilia | |||

| Pill-induced | |||

| Pain made worse by: | |||

| Solid food only | Obstructive dysphagia | ||

| Solids and liquids | Neuromuscular dysphagias | ||

| Regurgitation of old food | Zenker's diverticulum | ||

| Weakness and dysphagia | Cerebrovascular accidents, muscular dystrophies, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis | ||

| Halitosis | Zenker's diverticulum | ||

| Dysphagia relieved with repeated swallows | Achalasia | ||

| Dysphagia made worse with cold foods | Neuromuscular motility disorders | ||

A patient's general health information should be reviewed, including long-term illnesses, current prescription medications, and alcohol and tobacco use. While the literature does not describe dysphagia caused by non-prescription drugs, it is always reasonable to inquire about this. Commonly prescribed medications can cause dysphagia in either the oropharyngeal or esophageal stages of swallowing (Table 3).10,11 Antibiotics (doxycycline [Vibramycin], tetracycline, clindamycin [Cleocin], trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [Bactrim, Septra]) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the most common causes of direct mucosal injury to the esophagus, while potassium chloride tablets can cause the most severe injury. Anticholinergics, alpha adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and many short- and long-acting antihistamines can cause xerostomia.

| Medications that can cause direct esophageal mucosal injury10 |

| Antibiotics |

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin) |

| Tetracycline |

| Clindamycin (Cleocin) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Alendronate (Fosamax) |

| Zidovudine (Retrovir) |

| Ascorbic acid |

| Potassium chloride tablets (Slow-K)* |

| Theophylline |

| Quinidine gluconate |

| Ferrous sulfate |

| Medications, hormones and foods associated with reduced lower esophageal sphincter tone and reflux11 |

| Butylscopolamine |

| Theophylline |

| Nitrates |

| Calcium antagonists |

| Alcohol, fat, chocolate |

| Medications associated with xerostomia11 |

| Anticholinergics: atropine, scopolamine (Transderm Scop) |

| Alpha adrenergic blockers |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers |

| Antiarrhythmics |

| Disopyramide (Norpace) |

| Mexiletine (Mexitil) |

| Ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) |

| Antihistamines |

| Diuretics |

| Opiates |

| Antipsychotics |

OROPHARYNGEAL LOCALIZATION

Patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia present with difficulty in initiating swallowing and may also have associated coughing, choking or nasal regurgitation. The patient's speech quality may have a nasal tone. These dysphagias are most often associated with stroke, Parkinson's disease or other long-term neuromuscular disorders. Local structural lesions are less common.

ESOPHAGEAL LOCALIZATION

Patients with esophageal dysphagia present with the sensation of food sticking in their throat or chest. The patient's description of the perceived location of the obstruction often does not correlate well with actual pathology, especially if the perceived location is in the cervical area. Motility disorders and mechanical obstructions are common. Several medications have been associated with direct esophageal mucosal injury while others can decrease lower esophageal sphincter pressures and cause reflux (Table 3).10,11

NEUROMUSCULAR MOTILITY DISORDERS

Patients with neuromuscular dysphagia experience gradually progressive difficulty in swallowing solid food and liquids. Cold foods often aggravate the problem. Patients may succeed in passing the food bolus by repeated swallowing, by performing the Valsalva maneuver or by making a positional change. They are more likely to experience pain when swallowing than patients with simple obstruction. Achalasia, scleroderma and diffuse esophageal spasm are the most common causes of neuromuscular motility disorders.

MECHANICAL OBSTRUCTION

Obstructive pathology is typically associated with dysphagia of solid food but not liquids. Patients may be able to force food through the esophagus by performing a Valsalva maneuver, or they may regurgitate undigested food. Close questioning of the patient may reveal a change in diet to one of predominantly soft foods. Rapidly progressive dysphagia of a few months' duration suggests esophageal carcinoma. Weight loss is more predictive of a mechanical obstructive lesion.12 Peptic stricture, carcinoma and Schatzki's ring are the predominant obstructive lesions.

Physical Examination

A general physical examination and focused organ- or symptom-specific examinations based on the patient's history often identify the etiology of dysphagia.

Neurologic evaluation should include assessments of the patient's mental status, motor and sensory functioning, deep tendon reflexes and cranial nerves, and a cerebellar examination. Patients with impaired cognitive functioning and those who are under sedation should be carefully assessed, because these neurologic states can interfere with swallowing. Motor and sensory examinations may reveal a new stroke or identify a long-term illness. Special attention should be focused on the cranial nerves that are associated with swallowing, particularly the motor components of cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X and XII, and sensory fibers from cranial nerves V, VII, IX and X. A decreased gag reflex is associated with an increased risk of aspiration.13 A “wet voice” may suggest long-term laryngeal aspiration, while a weak, breathy voice may indicate vocal cord pathology.

Adequate saliva production results in a pink, well-hydrated oral cavity. Certain medications induce xerostoma preventing adequate mixing and propulsion of the food bolus into the posterior oropharynx (Table 3).10,11 A tongue blade and handheld mirror allow indirect inspection of the soft palate and vocal cord mobility. Physicians who are skilled in nasopharyngoscopy can directly view the vocal cords and hypopharynx. Bimanual palpation of the floor of the mouth, tongue and lips with a gloved hand detects masses and abnormal motor function. Examination of the teeth can reveal signs of inflammation or other structural disorders.

Observing the patient swallowing a variety of liquids and solids can be helpful. The patient should demonstrate enough neuromuscular control to chew food, mix it into a bolus with saliva and propel it to the posterior pharynx without choking or coughing. Elevation of the larynx during the swallowing reflex protects the airway and opens the upper esophageal sphincter. Normal laryngeal ascent can be palpated by placing the index finger above the patient's thyroid cartilage when the patient swallows. The cartilage should move cephalad against the physician's finger.

Thyroid masses and lymphadenopathy that cause obstructive dysphagia can be palpated on examination of the neck. A widened anteroposterior chest diameter and distant breath sounds are signs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which could be caused by long-term aspiration. The patient's abdomen should be examined for masses and organomegaly. The presence of occult blood in the stool may be a sign of neoplasms or esophagitis.

Laboratory Evaluation

Initial laboratory evaluations should be limited to specific studies based on the differential diagnosis generated after the completion of a history and physical examination. A complete blood count screens for infectious or inflammatory conditions. Thyroid function studies may detect hypo- or hyperthyroid-associated causes of dysphagia (e.g., Grave's disease or thyroid carcinoma). Other studies should be based on specific clinical conditions.

Special Studies

Although a patient history and physical examination identify the etiology of dysphagia in most patients, further testing may be indicated to confirm the diagnosis or to establish the patient's risk of aspiration (Figure 314 and Table 4). Subspecialists in radiology or gastroenterology will most often conduct these tests. Some centers have multidisciplinary dysphagia teams available to offer comprehensive diagnostic evaluations and therapeutic interventions.

| Barium swallow studies |

| Suspected obstructive lesion (e.g., Schatzki's ring, tumor) |

| Suspected esophageal motility disorder |

| Double-contrast upper gastrointestinal evaluation |

| Suspected esophageal mucosal injury |

| Evaluation of oropharyngeal anatomy and function (fluoroscopy) |

| Suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| Gastroesophageal endoscopy |

| Suspected acute obstructive lesion (impacted food bolus) |

| Evaluation of the esophageal mucosa |

| Confirmation of a positive barium study with biopsies or cytology |

| Manometry |

| Abnormality not identified on barium study or by endoscopy |

| pH monitoring |

| Suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| Videoradiography |

| Suspected risk of aspiration |

NASOPHARYNGOSCOPY

Nasopharyngoscopy is particularly useful in evaluating patients with oropharyngeal dysphagias. This procedure quickly identifies structural masses and lesions, and assesses laryngeal sensitivity to contact. Overuse of topical anesthetics can anesthetize the pharynx and confuse the interpretation. Under direct observation from the level of the soft palate, the physician assesses oral containment of a colored fluid bolus in the mouth and observes pooling of fluids around the vallecula or clearing of the fluid from the oropharynx into the esophagus. Patients who show aspiration without cough are at high risk of pulmonary complications.

BARIUM STUDIES

A barium study (esophagram) is often the first step in evaluating patients with dysphagia, especially if an obstructive lesion is suspected. It identifies intrinsic and extrinsic structural lesions but lacks precision in identifying the nature of obstructive lesions. A barium study assesses motility better than endoscopy and is relatively inexpensive with few complications; however, it can be difficult to perform in sick or uncooperative patients.

Double-contrast studies provide better visualization of esophageal mucosa. Barium marshmallows or pills localize obstructive lesions in the mouth or esophagus. Fluoroscopy can identify abnormalities in the mouth and oropharynx and, if observed closely, can provide some detail about function, detecting reflux and abnormal peristalsis.

ENDOSCOPY

Gastroesophageal endoscopy provides the best assessment of the esophageal mucosa.15 Masses or other lesions identified by barium studies should initiate esophagogastroscopy with biopsy and cytology. In patients with acute onset of dysphagia while eating, gastroesophageal endoscopy can directly remove an impacted food bolus and dilate strictures. Endoscopy has the added benefit of detecting infection and erosions, and providing biopsy capability. While endoscopy does not assess motor function or subtle strictures as well as barium studies15 (its sensitivity for detecting Schatzki's rings is only 58 percent, compared with 95 percent for barium study), a consensus panel making final diagnoses in patients with dysphagia found that for all dysphagia diagnoses, gastroesophageal endoscopy is more sensitive (92 percent versus 54 percent) and more specific (100 percent versus 91 percent) than double-contrast upper gastrointestinal radiography.16 One author suggests that the higher cost of gastroesophageal endoscopy may be offset by lower subsequent medical costs because of its improved accuracy in diagnosing dysphagia.17

VIDEORADIOGRAPHIC STUDIES

Patients at risk for silent aspiration (e.g., stroke, neurologic impairment) may benefit from videoradiographic studies that are performed by a team composed of a radiologist, an otolaryngologist and a speech pathologist with expertise in swallowing disorders.17 This evaluation uses quantifiable measures of swallows of a variety of bolus consistencies to help objectively identify the presence, nature and severity of oropharyngeal swallowing problems and to assess treatment options. Compared with upper gastrointestinal radiography, videoradiographic studies are better in identifying patients with mild strictures and extrinsic compressions (e.g., tumors or osteoarthritic spurs of the vertebrae).12 These studies are more expensive because of the special expertise, equipment and facilities required.

MANOMETRY

Manometry assesses motor function of the esophagus and is indicated if no abnormality is identified by barium study or gastroesophageal endoscopy.18 A catheter with multiple electronic pressure probes is passed into the stomach, measuring esophageal contractions and defining upper and lower esophageal responses to swallowing. Manometry detects definitive abnormalities in only 25 percent of patients with nonobstructive lesions. Its use in disorders of the oropharyngeal upper esophageal sphincter is not particularly effective, because patients do not tolerate the procedure well.

PH MONITORING

Despite several drawbacks, esophageal pH monitoring remains the gold standard for diagnosing patients with suspected reflux disease.19 A nasogastric probe is inserted into the patient's esophagus and records pH levels. These levels are compared with the patient's record of symptoms over a 24-hour period to determine if acid reflux contributes to the symptoms. Combined recordings of esophageal pH levels and intraluminal esophageal pressure may aid in diagnosing patients with reflux-induced esophageal spasm.

OTHER IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Plain radiographic films of the chest or neck offer limited information unless structural abnormalities are noted. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans provide excellent definition of structural abnormalities, particularly when used to evaluate patients with suspected central nervous system causes of dysphagia. Ultrasonography of the pharynx and tongue offers no benefit compared with videofluorography, but ultrasonography may aid in the evaluation of submucosal and extramural lesions of the esophagus. Radionuclide studies may be used to evaluate transit function through the esophagus.

Final Comment

Family physicians can reduce the symptoms and risks of complications by early and aggressive evaluation and management of stroke patients. Physicians should recommend that all patients, especially the elderly, take their medications with a full glass of water while in an upright position well before bedtime. Patient referral is warranted when the cause of dysphagia is unclear, when there is evidence of aspiration or if further diagnostic or therapeutic expertise is necessary.