Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(12):2247-2253

Histoplasmosis is an endemic infection in most of the United States and can be found worldwide. The spectrum of this illness ranges from asymptomatic infection to severe disseminated disease. Life-threatening illness is usually associated with an immunocompromised state; however, 20 percent of severe illnesses result from a heavy inoculum in healthy persons. Culture remains the gold standard for diagnosis but requires a lengthy incubation period. Fungal staining produces quicker results than culture but is less sensitive. Testing for antigen and antibodies is rapid and sensitive when used for particular disease presentations. An advantage of antigen detection is its usefulness in monitoring disease therapy. Antifungal therapy is indicated in chronic or disseminated disease and severe, acute infection. Amphotericin B is the agent of choice in severe cases; however, patients must be monitored for nephrotoxicity and hypokalemia. Itraconazole is effective in moderate disease and is well tolerated, even with long-term use. Hepatotoxicity, the most severe adverse effect of itraconazole, is uncommon and usually transient.

Histoplasmosis is an endemic infection in most of the United States. Disseminated disease is rare but can be fatal if untreated. This article presents the manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of histoplasmosis, beginning with the case of an immunocompetent child who developed disseminated disease.

Illustrative Case

A six-year-old boy was referred to a pediatric infectious disease clinic after a three-week history of fever, mild nonproductive cough, pallor, and fatigue. His oral temperature was 40.6°C (105.1°F), and he had occasional rigors, emesis, and night sweats.

Outpatient work-up revealed interstitial pneumonitis on chest radiograph; pancytopenia (platelet count, 72,000 per mm3 [72 × 109 per L]; hemoglobin, 8.9 g per dL [89 g per L]); and mildly abnormal results on liver function tests. Blood cultures, febrile agglutinins, and an infectious mononucleosis screen were all negative. Despite the use of antibiotics, the patient's disease progressed, leading to his referral to the infectious disease clinic and admittance to the children's hospital for further evaluation.

The patient's previous medical history was unremarkable. He lived on a farm in Kentucky with his parents and two siblings, and there was no known history of ill contacts, nearby construction, contact with birds or bats, recent travel, ingestion, tick bite, or other exposures. His family history was non-contributory.

At presentation he was found to be well developed and well nourished but very pale, and he appeared ill. He was tachycardic and tachypneic, with an axillary temperature of 39.1°C (102.4°F). His abdomen was severely distended, with liver and spleen palpable to just above the pelvic brim. Laboratory findings revealed worsening pancytopenia and liver function. A chest radiograph showed diffuse, fine, nodular interstitial prominence and superior mediastinal widening.

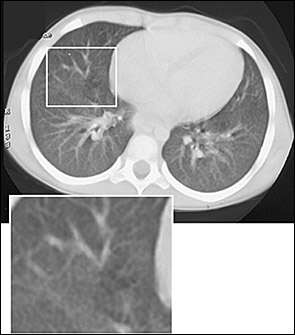

On admission, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed diffuse miliary pulmonary infiltrates without mediastinal mass or lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Bone marrow examination showed no evidence of malignancy. Empiric therapy for tuberculosis and histoplasmosis was initiated. Fungal elements consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum were later identified on bone marrow slides, and bone marrow cultures eventually revealed moderate growth of H. capsulatum. Urine antigen and serologic assays for histoplasmosis were positive. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative.

The antitubercular drug regimen was discontinued, and oral itraconazole was added to the amphotericin therapy. After showing marked improvement, the boy was discharged from the hospital on day 9. Amphotericin therapy was continued for a total of 16 days and itraconazole for six months. The patient also received six weeks of potassium supplementation for amphotericin-related hypokalemia. Within three months of discharge he was asymptomatic, with a normal physical examination. At six months, his urine antigen level was still elevated but significantly decreased. Antigen levels are usually monitored until results are negative but, because this patient was doing well enough after three months of itraconazole therapy, he was released to the care of a pediatrician. Further questioning revealed that the patient had been exposed to debris removed from the ventilation system when the heater was started for the winter. The heating ducts may have held fungal spores propagated by bats living in a chimney.

Epidemiology

H. capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus found in the temperate zones of the world; it is highly endemic in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys of the United States.1 An estimated 40 million people in the United States have been infected with H. capsulatum, with 500,000 new cases occurring each year.2 The mycelial form of H. capsulatum is found in the soil, especially in areas contaminated with bird or bat droppings, which provide added nutrients for growth. Infections in endemic areas are typically caused by wind-borne spores emanating from point sources such as bird roosts, old houses or barns, or activities involving disruption of the soil such as farming and excavation.3 H. capsulatum infection is not transmissible through person-to-person contact.

Pathogenesis

When spores produced by the mycelial form of H. capsulatum become airborne, they are inhaled and deposited in alveoli. At normal body temperature (37°C [98.6°F]), the spores germinate into the yeast form of this dimorphic fungus and are ingested by pulmonary macrophages. The yeasts become parasitic, multiply within these cells,3 and travel to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, where they gain access to the blood circulation that disseminates them to various organs. Macrophages throughout the reticuloendothelial system ingest and sequester the organism.1

About 10 to 14 days after exposure, cellular immunity develops, and macrophages become fungicidal and clear an immunocompetent host of infection.4 Necrosis develops at the sites of infection in the lungs, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow, leading to caseation, fibrous encapsulation, calcium deposition and, within a few years of the primary infection, calcified granulomas.1,4 Any defects in cellular immunity result in a progressive disseminated form of infection that can be lethal.1

Clinical Presentation

ASYMPTOMATIC PRIMARY INFECTION

The majority of people with normal immunity who develop histoplasmosis manifest an asymptomatic or clinically insignificant infection (Table 1).4,5 The most common abnormality on chest radiograph is a solitary pulmonary nodule. Cavitation is rare, but adenopathy (particularly hilar and mediastinal) is seen frequently.1

| Asymptomatic primary infection | |

| Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis | |

| Sequelae: mediastinal granuloma, pericarditis, rheumatologic syndromes | |

| Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis | |

| Disseminated histoplasmosis | |

| Other: mediastinal fibrosis, central nervous system histoplasmosis, broncholithiasis | |

ACUTE PULMONARY HISTOPLASMOSIS

Symptomatic illness is primarily caused by an intense exposure (e.g., cleaning an attic or a chicken coop), and the severity of disease is related to the number of spores inhaled.1 Cellular immunity attained through previous exposure decreases the incidence and severity of symptomatic infections. Therefore, infants and children are affected more frequently than adults.1

Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis manifests as a diverse clinical spectrum ranging from a brief period of malaise to a severe, protracted illness (Table 1).4,5 Common symptoms include fever, headache, nonproductive cough, chills, pleuritic chest pain, weight loss, malaise, myalgias, and sweats. With a larger inoculum, patients may exhibit dyspnea with hypoxia. The physical examination is frequently unremarkable; however, hepatosplenomegaly, adenopathy, erythema nodosum, and erythema multiforme can be encountered.1,6

Acute pulmonary infections are not typically associated with abnormalities on chest radiography. Single or multiple patches of airspace disease (particularly in the lower lung zones) are the most frequent abnormal findings.1 Hilar and mediastinal adenopathy is sometimes present, and more severe infections frequently show small diffuse pulmonary nodules.1

Mediastinal granuloma, pericarditis, and rheumatologic syndromes (i.e., arthritis) are possible sequelae following acute infections of pulmonary histoplasmosis (Table 1).4,5 Actively inflamed mediastinal lymph nodes cause chest pain, cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea because of airway or vascular compression, and the clinical course is extremely variable.4,5 Pericarditis is caused by an immune reaction to histoplasma infection in mediastinal lymph nodes.4,5 Patients present with chest pain and fever weeks to months after the pulmonary infection.4 Despite the risk of hemo-dynamic compromise, long-term outcome is excellent.4,5 Arthritis may occur as an inflammatory reaction to the primary infection, and distribution is often symmetric and polyarticular.4,5 Symptoms usually resolve spontaneously or following treatment with anti-inflammatory agents. Radiographs are normal.4

CHRONIC PULMONARY HISTOPLASMOSIS

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis (Table 1)4,5 is associated with preexisting abnormal lung architecture, especially emphysema,1,3,6,7 and occurs most commonly in white, middle-aged men.3 Symptoms (malaise, productive cough, fever, and night sweats) are similar to those of tuberculosis but are usually less severe. The progressive disease process that ends in necrosis and loss of lung tissue results from a hyperimmune reaction to fungal antigens rather than from the infection itself.1,4

DISSEMINATED HISTOPLASMOSIS

Disseminated histoplasmosis is a rare disease that occurs primarily in immunocompromised persons, especially in patients with HIV infection and a CD4 lymphocyte count that is below 150 to 200 per mm3 (150 to 200 × 106 per L).7 Patients with lymphoreticular neoplasms and patients who are receiving corticosteroids, cytotoxic therapy, and immunosuppressive agents are also predisposed to disseminated histoplasmosis.1,3,7,8 About 20 percent of cases of this disorder occur in otherwise healthy persons who have received a heavy inoculum.9 The risk of disseminated disease increases with age.1,3,4

The spectrum of illness in disseminated disease ranges from a chronic, intermittent course in immunocompetent persons to an acute and rapidly fatal infection that usually occurs in infants and severely immunosuppressed persons.3,4 Fever is the most common symptom; however, headache, anorexia, weight loss, and malaise are frequent complaints. Cough is present in less than one half of cases, and gastrointestinal problems are rare.3,4 Physical examination may reveal hepatosplenomegaly and lymph-adenopathy or, less frequently, mucocutaneous lesions such as oropharyngeal ulceration.4,7

Laboratory evaluation frequently reveals pancytopenia caused by bone marrow involvement and abnormal results on hepatic function tests, indicating that the disease has spread to the liver.1,3,4 Chest radiographs may be normal but usually display small, diffuse, nodular opacities.1,3,4 Diffuse, interstitial infiltrates are common; however, diffuse airspace disease and adenopathy are rare.1

OTHER PRESENTATIONS

DIAGNOSIS

Histoplasmosis can be diagnosed by culture, fungal stains, serologic tests for antibodies, and antigen detection (Table 2).4 Skin testing is rarely useful as a diagnostic measure because of high background positivity in endemic areas and false-negative results associated with chronic pulmonary and disseminated disease.4,7

| Sensitivity (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Disseminated histoplasmosis | Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis | Self-limited manifestations* | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Antigen | 92 | 21 | 39 | Rapid | |

| Sensitive in disseminated disease Useful in monitoring therapy | Poor sensitivity in chronic and self-limited disease | ||||

| Culture | 85 | 85 | 15 | Gold standard | 2- to 4-week incubation |

| Definitive diagnosis | Low sensitivity in self-limited disease | ||||

| Fungal stain | 43 | 17 | 9 | Rapid | Low sensitivity |

| Identification errors | |||||

| Serology | 71 | 100 | 98 | Rapid | |

| Sensitive in chronic and self-limited disease | False-negative and false-positive responses | ||||

Fungal staining of tissue and blood is rapid but has a significantly lower sensitivity than culture or antigen detection.4,10 Bone marrow produces the highest yield, staining positive in as many as 75 percent of cases of disseminated disease.4,10 Differentiating H. capsulatum from Candida glabrata and Pneumocystis carinii can be difficult.4,10

Serologic tests that detect antibodies to H. capsulatum are rapid and relatively sensitive but have some limitations. False-negative results can occur in immunocompromised patients and during the six-week postexposure period while antibodies are still developing.4,11,12 False-positive results may be associated with cross-reactivity with other fungi, especially blastomyces and aspergillus.4,10 Because antibody titers remain elevated for up to five years after treatment, differentiating active from inactive infections and evaluating for relapse can be problematic.4,10,12

Antigen detection is a rapid means of diagnosis in patients with disseminated disease. Sensitivity is greater with urine (92 percent) than other fluids; however, optimal diagnostic yield is the result of testing both urine and serum.4 Cross-reactivity is rare in this case, compared with serologic assays. Because antigen levels decrease with effective treatment and increase with relapse, this method is a useful tool in monitoring therapy.10–13

TREATMENT

Treatment of histoplasmosis depends on the severity of the clinical syndrome. Mild cases may require only symptomatic measures, but antifungal therapy is indicated in all cases of chronic or disseminated disease and in severe or prolonged acute pulmonary infection4 (Table 3).5 Treatment should be continued until all clinical findings have resolved and H. capsulatum antigen levels have returned to normal.4,5 In patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), lifelong suppressive therapy is required to prevent relapse.4–7,9,14 In immunocompetent patients with acute pulmonary disease and respiratory compromise, corticosteroids may be helpful as adjunctive therapy.5

| Type of histoplasmosis | Treatment of severe manifestations | Treatment of moderate or mild manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Acute pulmonary | Amphotericin B (Fungizone IV), 0.7 mg per kg per day* with corticosteroids† (prednisone [Deltasone], 60 mg daily for 2 weeks), then itraconazole (Sporanox), 200 mg once or twice daily* for 12 weeks | Symptoms less than four weeks: none |

| Symptoms more than four weeks: itraconazole, 200 mg once or twice daily for six to 12 weeks | ||

| Chronic pulmonary | Amphotericin B,‡ then itraconazole for 12 to 24 months | Itraconazole for 12 to 24 months |

| Disseminated (in patients without AIDS) | Amphotericin B, 0.7 to 1.0 mg per kg per day,‡ then itraconazole for six to 18 months§ | Itraconazole for six to 18 months |

| Disseminated (in patients with AIDS) | Induction: amphotericin B,‡ then itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily, to complete a 12-week course | Induction: itraconazole, 200 mg three times daily for three days, then twice daily to complete a 12-week course |

| Maintenance: itraconazole for life | ||

| Maintenance: itraconazole for life | ||

| Granulomatous mediastinitis | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole for six to 12 months; also consider corticosteroids and/or surgical resection∥ | Itraconazole for six to 12 months |

| Pericarditis | Corticosteroids¶ and/or pericardial drainage | NSAIDs for two to 12 weeks |

| Rheumatologic | NSAIDs for two to 12 weeks | NSAIDs for two to 12 weeks |

Amphotericin B (Fungizone IV) is considered the treatment of choice in severe or disseminated disease.4–7,9,14–18 A decrease in fever occurs within a week of treatment in the majority of patients.4 Treatment can usually be changed to itraconazole (Sporanox) within three to 14 days, which is desirable because amphotericin is associated with toxicity and requires intravenous administration.4 Nephrotoxicity, the most serious adverse effect, is manifested by azotemia or hypokalemia requiring potassium supplementation.15 Normocytic anemia can also occur but, like azotemia, usually resolves after discontinuation of the medication.15

Itraconazole is an effective treatment in mild or moderate cases of disseminated histoplasmosis, as well as in acute and chronic pulmonary disease.4,7,16 Although itraconazole is not as rapid-acting as amphotericin, it has the advantage of being well tolerated even in long-term use.4,15 Most side effects, including headache, dizziness, and gastrointestinal symptoms, are transient.15 Biliary excretion eliminates the need for adjusting dosages in patients with renal disease.15

Abnormal results on liver function tests are possible, but levels typically return to normal on completion of therapy. The risk of hepatitis is rare.15 Careful monitoring and assessment of the risks and benefits are recommended to prevent unnecessary discontinuation of this drug.

Fluconazole (Diflucan) is less effective than amphotericin B or itraconazole in the treatment of histoplasmosis7,17,19,20 and is associated with more relapses.17,20 Unlike itraconazole, fluconazole enters the cerebrospinal fluid.5 Therefore, fluconazole therapy is reserved for use in patients with mild to moderate disease who cannot take itraconazole17 and patients with meningitis.5,15