A more recent article on vaginitis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(5):321-329

Patient information: See related handout on vaginitis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Vaginitis is defined as any condition with symptoms of abnormal vaginal discharge, odor, irritation, itching, or burning. The most common causes of vaginitis are bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis. Bacterial vaginosis is implicated in 40% to 50% of cases when a cause is identified, with vulvovaginal candidiasis accounting for 20% to 25% and trichomoniasis for 15% to 20% of cases. Noninfectious causes, including atrophic, irritant, allergic, and inflammatory vaginitis, are less common and account for 5% to 10% of vaginitis cases. Diagnosis is made using a combination of symptoms, physical examination findings, and office-based or laboratory testing. Bacterial vaginosis is traditionally diagnosed with Amsel criteria, although Gram stain is the diagnostic standard. Newer laboratory tests that detect Gardnerella vaginalis DNA or vaginal fluid sialidase activity have similar sensitivity and specificity to Gram stain. Bacterial vaginosis is treated with oral metronidazole, intravaginal metronidazole, or intravaginal clindamycin. The diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis is made using a combination of clinical signs and symptoms with potassium hydroxide microscopy; DNA probe testing is also available. Culture can be helpful for the diagnosis of complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis by identifying nonalbicans strains of Candida. Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis involves oral fluconazole or topical azoles, although only topical azoles are recommended during pregnancy. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends nucleic acid amplification testing for the diagnosis of trichomoniasis in symptomatic or high-risk women. Trichomoniasis is treated with oral metronidazole or tinidazole, and patients' sex partners should be treated as well. Treatment of noninfectious vaginitis should be directed at the underlying cause. Atrophic vaginitis is treated with hormonal and nonhormonal therapies. Inflammatory vaginitis may improve with topical clindamycin as well as steroid application.

Vaginitis is characterized by vaginal symptoms, including discharge, odor, itching, irritation, or burning.1 Most women have at least one episode of vaginitis during their lives,2 making it the most common gynecologic diagnosis in primary care. Studies have shown a negative effect on quality of life in women with vaginitis, with some women expressing anxiety, shame, and concerns about hygiene, particularly in those with recurrent symptoms.3–8

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC

Vaginitis

A 2013 meta-analysis showed that oral or topical antibiotic treatment of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy does not prevent preterm birth, even in women with a history of preterm labor in previous pregnancies.

Newer laboratory tests such as DNA and antigen testing for bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis, or vaginal fluid sialidase testing for bacterial vaginosis, may have similar or better sensitivity and specificity compared with traditional office-based testing. However, comparative cost-effectiveness has not been studied.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms alone cannot differentiate between the causes of vaginitis. Office-based or laboratory testing should be used with the history and physical examination findings to make the diagnosis. | C | 10–12 |

| Do not obtain culture for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis because it represents a polymicrobial infection. | C | 9 |

| Nucleic acid amplification testing is recommended for the diagnosis of trichomoniasis in symptomatic or high-risk women. | C | 9 |

| Treatment of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy improves symptoms but does not reduce the risk of preterm birth. | A | 44, 45 |

| In nonpregnant women, oral and vaginal treatment options for uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis have similar clinical cure rates. | B | 47 |

The most common causes of vaginitis are bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis. Bacterial vaginosis is the cause in 40% to 50% of cases in which a cause is identified, with vulvovaginal candidiasis accounting for 20% to 25% and trichomoniasis for 15% to 20% of cases. Noninfectious causes, including atrophic, irritant, allergic, and inflammatory vaginitis, are less common and account for 5% to 10% of vaginitis cases.9

General Diagnostic Considerations

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The history alone is unreliable for the diagnosis of different causes of vaginitis.10 Physical examination findings and office-based or laboratory test results should be used with the history to determine the diagnosis.11–13 Characteristic clinical signs and symptoms for different causes of vaginitis are listed in Table 1.10,14,15 Risk factors for vaginitis are listed in Table 2.9,14,16

| Diagnosis | Etiology | Symptoms | Signs | Other risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis | Anaerobic bacteria (Prevotella, Mobiluncus, Gardnerella vaginalis, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma) | Fishy odor; thin, homogenous discharge that may worsen after intercourse; pelvic discomfort may be present | No inflammation | Increased risk of HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes infections |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Candida albicans, can have other Candida species | White, thick, cheesy, or curdy discharge; vulvar itching or burning; no odor | Vulvar erythema and edema | — |

| Trichomoniasis | Trichomonas vaginalis | Green or yellow, frothy discharge; foul odor; vaginal pain or soreness | Inflammation; strawberry cervix | Increased risk of HIV infection Increased risk of preterm labor Should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections |

| Atrophic vaginitis | Estrogen deficiency | Thin, clear discharge; vaginal dryness; dyspareunia; itching | Inflammation; thin, friable vaginal mucosa | — |

| Irritant/allergic vaginitis | Contact irritation or allergic reaction | Burning, soreness | Vulvar erythema | — |

| Inflammatory vaginitis | Possibly autoimmune | Purulent vaginal discharge, burning, dyspareunia | Vaginal atrophy and inflammation | Associated with low estrogen levels |

| Type of vaginitis | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis | Low socioeconomic status, vaginal douching, smoking, new or multiple sex partners, unprotected intercourse, women who have sex with women |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | Recent antibiotic use, pregnancy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, AIDS, corticosteroid use, other immunosuppression |

| Trichomoniasis | Low socioeconomic status, multiple sex partners, other sexually transmitted infections, unprotected intercourse, drug use, smoking |

| Atrophic or inflammatory vaginitis | Menopause, lactation, oophorectomy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunologic disorders, premature ovarian failure, endocrine disorders, antiestrogen medications |

| Irritant vaginitis | Soaps, tampons, contraceptive devices such as condoms or diaphragms, sex toys, pessaries, topical products, douching, fastidious cleansing, medications, clothing |

| Allergic vaginitis | Sperm, douching, latex condoms or diaphragms, tampons, topical products, medications, clothing, atopic history |

Signs and symptoms that increase the likelihood of vulvovaginal candidiasis vs. bacterial vaginosis are a cheesy, curdy, or flocculent discharge; itching; vulvar or vaginal inflammation or redness; and lack of odor.10 A fishy odor makes candidiasis less likely.10 Normal physiologic vaginal discharge is clear to white, not malodorous, not accompanied by discomfort or pruritus, and the quantity varies during a woman's menstrual cycle.

OFFICE AND LABORATORY TESTING

Office-based tests include microscopy, measurement of vaginal pH, and whiff test. A speculum is not required for collecting vaginal fluid samples for these tests.17 Several studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between samples from patient self-collected swabs and those collected by clinicians for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis, with sensitivities of 70% to 100% and specificities of 97% to 100%.18–22 It is reasonable to conclude that samples for office-based microscopy and laboratory testing for other causes of vaginitis can be collected by patients as well. Patients should be instructed to insert the swab at least one inch into the vagina.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

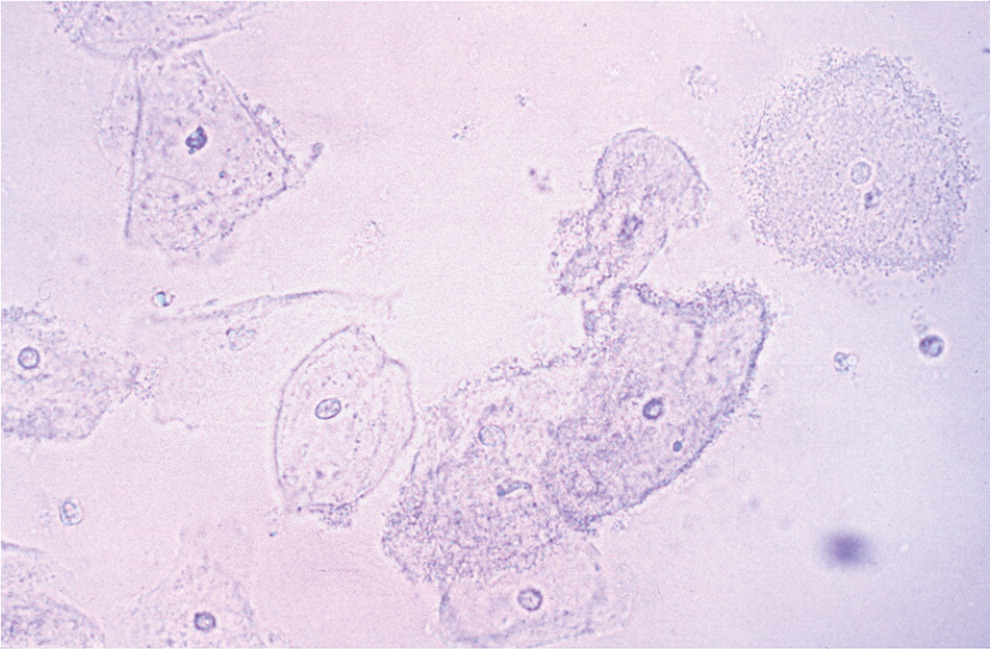

Although Gram stain is considered the diagnostic standard, bacterial vaginosis is traditionally diagnosed using the Amsel criteria (Table 3).14,23 Criteria include thin, homogenous discharge; a positive whiff test; the presence of clue cells on microscopy (Figure 114); and a vaginal pH greater than 4.5. Three out of four criteria are required to make the diagnosis, with sensitivity ranging from 70% to 97% and specificity from 90% to 94%, compared with Gram stain.24,25 Newer methods of laboratory testing with DNA probe for Gardnerella vaginalis or detection of vaginal fluid sialidase activity have sensitivities of 92% to 100% and specificities of 92% to 98% compared with Gram stain.26–28

Vaginal culture and Papanicolaou (Pap) testing are not useful for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis because it is a polymicrobial infection.9 Group B streptococcus may be found on culture and has been associated with vaginitis symptoms, although there is no expert consensus on treatment in nonpregnant women.29

Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is common. Women should be advised to return for treatment if symptoms recur. Routine testing in asymptomatic women and retesting (test of cure) are not recommended because these bacteria can be part of normal flora.

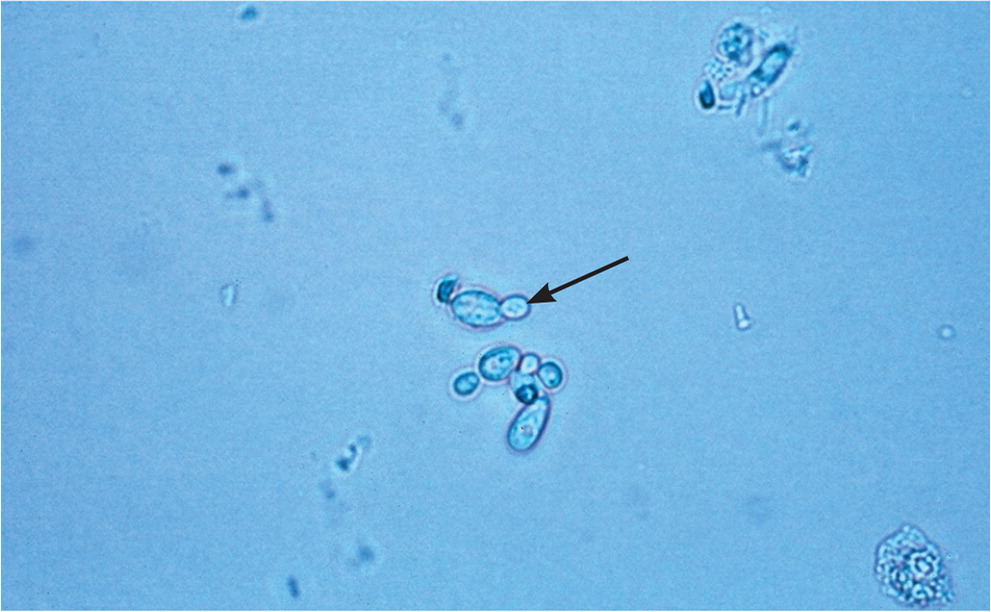

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Vulvovaginal candidiasis can be diagnosed by visualization of yeast hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation (Figure 214) in a woman with typical symptoms. It can also be diagnosed using antigen or DNA probe testing, with sensitivities of 77% to 97% and specificities of 77% to 99%, compared with culture as the diagnostic standard.30–32 Women with vulvovaginal candidiasis have a normal acidic vaginal pH.

Complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis is defined as recurrent (four or more episodes in one year) or severe infections, or infections that occur in a patient who is immunocompromised, such as someone with AIDS or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Culture is particularly important for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis, because patients are more likely to have an infection with nonalbicans strains of Candida, which may require different treatment (Table 4).9,16 Candidal species and anaerobes can be normal flora in asymptomatic women, so retesting (test of cure) is not recommended in the absence of symptoms.

| Initial regimens | Alternative regimens | Pregnancy | Recurrence | Treatment of sex partners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial vaginosis | ||||

| Metronidazole (Flagyl), 500 mg orally twice daily for seven days* or Metronidazole 0.75% gel (Metrogel), one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally daily for five days or Clindamycin 2% cream, one full applicator (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for seven days† | Tinidazole (Tindamax), 2 g orally once daily for two days or Tinidazole, 1 g orally once daily for five days or Clindamycin, 300 mg orally twice daily for seven days or Clindamycin (Cleocin Ovules), 100 mg intra-vaginally at bedtime for three days | Metronidazole, 500 mg orally twice daily for seven days | First recurrence:

| Routine treatment of sex partners is not recommended |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | ||||

| Topical azole therapy‡ (Table 5) or Fluconazole (Diflucan), 150 mg orally, single dose | — | Topical azole therapy applied intravaginally for seven days | To achieve mycologic cure§:

| Routine treatment of sex partners is not recommended unless the partner is symptomatic |

| Trichomoniasis | ||||

| Metronidazole, 2 g orally, single or divided dose on the same day or Tinidazole, 2 g orally, single dose | Metronidazole, 500 mg orally twice daily for seven days | Metronidazole, 2 g orally, single dose in any stage of pregnancy | Differentiate persistent or recurrent infection from reinfection‖ If metronidazole, 2-g single dose fails:

If metronidazole, 500 mg twice daily for seven days fails:

If above regimens fail:

| Concurrent treatment of sex partners is recommended Advise refraining from intercourse until partners are treated and symptom-free |

TRICHOMONIASIS

Trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted infection that should be considered in women at risk who present with vaginitis symptoms (Table 29,14,16). It can be diagnosed when motile, flagellated protozoa are observed on saline microscopy (Figure 314). However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends nucleic acid amplification testing for the diagnosis of trichomoniasis in symptomatic or high-risk women. These tests have a higher sensitivity than saline microscopy (95% to 100% vs. 51% to 65%9) and can be performed on endocervical, vaginal, or urine specimens, or on liquid-based Pap test samples. Vaginal culture also has a high sensitivity for identifying Trichomonas, but it has largely been replaced by nucleic acid amplification testing because of the longer time (up to one week) needed for results.9

Because trichomoniasis is sexually transmitted and has a high rate of recurrence, the CDC recommends testing for reinfection three months after treatment.9

NEWER LABORATORY TESTS

Some data show that newer laboratory tests such as DNA and antigen testing for bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis, or vaginal fluid sialidase testing for bacterial vaginosis, may have similar or better sensitivity and specificity compared with office-based testing.33 However, more comparisons with diagnostic standard testing (i.e., Gram stain for bacterial vaginosis and culture for vulvovaginal candidiasis) are needed. The costs of these tests range from approximately $17 for vaginal fluid sialidase testing to $27 to $49 for DNA testing, compared with $5 to $10 for office-based microscopy. No studies were found on the cost-effectiveness of these newer tests compared with office-based testing.

PAPANICOLAOU TESTS

When clue cells or hyphae are present on a Pap test, treatment depends on symptoms. Both can be normal findings in asymptomatic women.9 Also, physicians should treat trichomoniasis when found on a Pap test, but a normal result does not rule out infection.34 When seeking a diagnosis for vaginal symptoms at the same time as performing a Pap test, physicians can order testing on the liquid-based Pap fluid. These tests have similar sensitivity and specificity to vaginal samples.

OTHER CAUSES OF VAGINITIS

There is no cause of vaginitis identified in up to 30% of women. These women may have a range of conditions, including irritant or allergic vaginitis, atrophic vaginitis, or physiologic discharge.35 Inflammatory vaginitis is an uncommon condition characterized by purulent discharge, burning, and dyspareunia, and should be considered in patients with these symptoms if no infectious cause is found. Inflammatory vaginitis is associated with low estrogen levels, such as in menopausal or perimenopausal women.36

Treatment

First-line and alternative treatment regimens for vaginitis are presented in Table 4 with suggestions for recurrent infection, treatment during pregnancy, and treatment of sex partners.9,16 Additional considerations for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis are discussed.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

Treatment of bacterial vaginosis is recommended for resolving symptoms, as well as reducing the risk of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Trichomonas vaginalis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and herpes simplex virus type 2 infections.37 Shifts in vaginal flora have been associated with increased risk of these infections, leading researchers to conclude that treatment of bacterial vaginosis may decrease susceptibility to these infections.38,39

First-line therapy includes seven-day courses of oral metronidazole (Flagyl), intravaginal metronidazole (Metrogel), or intravaginal clindamycin.9 No significant difference in effectiveness has been demonstrated among these regimens.40 Patient preference should be considered when choosing an agent. Physicians should explain potential adverse effects with each regimen, including a possible disulfiram-like reaction with alcohol consumption or gastrointestinal symptoms in persons taking oral metronidazole, or possible weakening of latex condoms with the use of topical therapies containing oil-based preparations.9

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved a single-dose oral therapy for bacterial vaginosis, secnidazole (Solosec), which will be available in 2018.41 A randomized controlled trial demonstrated similar effectiveness and outcomes compared with metronidazole for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis.42 The dosing involves one-time oral administration of a 2-g packet of granules mixed into applesauce, yogurt, or pudding. A primary adverse effect of this regimen is vulvovaginal candidiasis. Data are insufficient on the safety of secnidazole use in pregnancy, and use is not recommended with breastfeeding.43

Bacterial Vaginosis in Pregnancy. In the past, treatment for bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy was recommended to prevent preterm births. Further review of the evidence has demonstrated that antibiotic treatment does not prevent preterm birth for women with symptomatic or asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis.44,45 Although a previous meta-analysis demonstrated a possible reduction in preterm labor with treatment of bacterial vaginosis, particularly in early pregnancy (before 20 weeks' gestation),46 a more recent meta-analysis of 21 studies found that antibiotic treatment—regardless of route of administration (oral or topical), the timing in pregnancy, or history of preterm labor in previous pregnancies—does not prevent preterm birth for women with symptomatic or asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis.45 Two studies cited in this meta-analysis that included the presence of abnormal vaginal flora as well as bacterial vaginosis showed a possible reduction in preterm labor before 37 weeks' gestation with treatment; therefore, further investigation may provide more information about the role of abnormal bacterial flora and its treatment in pregnancy.45 Regardless, treatment of bacterial vaginosis is generally recommended for symptomatic relief, and adverse effects of metronidazole in pregnancy have not been demonstrated.45

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

Treatment of candidal infection is aimed at reducing symptoms. There are several topical azole preparations and regimens available, as well as oral fluconazole (Diflucan) in a single 150-mg dose. All topical treatments listed in Table 5,9,16 as well as oral fluconazole, are recommended by the CDC as first-line therapy for vulvovaginal candidiasis.9 The choice of treatment should be made in conjunction with patient preference and previous experience with these agents. In nonpregnant patients, there is no definitive advantage of one treatment over another in terms of clinical or mycologic cure, with all treatment options having about an 80% cure rate.47,48 Limited data demonstrate that patients may prefer oral regimens.49–51

| Over-the-counter intravaginal agents |

| Clotrimazole 1% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for seven to 14 days |

| Clotrimazole 2% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for three days |

| Miconazole 2% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for seven days |

| Miconazole 4% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for three days |

| Miconazole 100-mg vaginal suppository, one suppository daily for seven days |

| Miconazole 200-mg vaginal suppository, one suppository daily for three days |

| Miconazole 1,200-mg vaginal suppository, one suppository for one day |

| Tioconazole 6.5% ointment, 5 g intravaginally in a single application |

| Prescription intravaginal agents |

| Butoconazole 2% cream (Gynazole-1, single-dose bioadhesive product), 5 g intravaginally in a single application |

| Terconazole 0.4% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for seven days |

| Terconazole 0.8% cream, 5 g intravaginally daily for three days |

| Terconazole 80-mg vaginal suppository, one suppository daily for three days |

There are several considerations when choosing between topical and oral treatment.52,53 Topical preparations may provide more immediate relief because of the soothing nature of topical treatment or, conversely, may cause local hypersensitivity reactions resulting in itching or burning. Oral fluconazole offers the advantage of one-dose convenience without messy creams or suppositories. Oral medications may cause systemic adverse effects, particularly gastrointestinal effects and toxicity in addition to potential medication interactions. An additional factor to consider is that topical azole creams and suppositories may be oil-based and can weaken latex condoms.9

Topical antifungals are available over the counter, and many patients self-diagnose and treat presumed vulvovaginal candidiasis with these products. However, studies have shown that, regardless of whether they have a history of vulvovaginal candidiasis, women are not able to accurately self-diagnose the condition, often using these products for causes of vaginitis other than candidal infections.54

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in Pregnancy. Vulvovaginal candidiasis is common during pregnancy. The CDC recommends that only topical azole therapies, applied for seven days, be used in pregnant women with vulvovaginal candidiasis.9 Although more data are needed, oral therapy may be associated with increased risk of miscarriage or fetal malformations, particularly at high doses.55,56

Complicated Vulvovaginal Candidiasis. Patients with complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis require more aggressive therapy. To guide treatment, it is helpful to consider whether a patient has recurrent infections and whether the etiology may be a nonalbicans species of Candida.

For patients with severe vulvovaginal candidiasis, a second dose of fluconazole given three days after the first dose has been shown to achieve significant improvement in short-term symptoms as well as prevent recurrence at 35 days. A second dose did not have significant effects for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis.57

For recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis caused by Candida albicans, initial intensive therapy with fluconazole for seven to 14 days (i.e., fluconazole, 150 mg, every three days for three doses) followed by weekly treatment with 150-mg fluconazole for six months has been shown to achieve symptomatic relief at one year for most patients.58

If severe or recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis does not respond to initial treatment, culture may guide therapy when nonalbicans species are identified. Infections with nonalbicans species are less responsive to fluconazole. Topical imidazoles (i.e., econazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, and ketoconazole) are more effective in eradication.59 In a small study, topical terconazole was also shown to relieve symptoms and achieve mycologic cure for about 50% of patients.60 For patients with nonalbicans infections who do not respond to these treatments, a regimen of 600-mg vaginal boric acid capsules daily for 14 days has been shown to be effective.61

Other nonpharmacologic regimens have been proposed for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. A meta-analysis did not demonstrate clear evidence for probiotics in the treatment of candidal vaginitis; however, more studies are needed because of small study size and varied probiotic regimens.62

TRICHOMONIASIS

Treatment of trichomoniasis can decrease symptoms and reduce transmission to partners. In addition, in persons with HIV infection, treatment of trichomoniasis may also decrease HIV transmission rates to partners.63

Although first-line therapy for trichomoniasis in pregnant and nonpregnant women is a single 2-g dose of metronidazole, patients with HIV infection treated with a seven-day course of metronidazole had lower rates of infection at test of cure and lower rates of reinfection at three months.9,64 Tinidazole (Tindamax) in a single 2-g dose is also a first-line treatment for trichomoniasis; however, it is more expensive. Metronidazole-resistant trichomoniasis, which would require tinidazole, is rare.65

Trichomoniasis in Pregnancy. Trichomoniasis has been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth.66 Symptomatic pregnant women, regardless of pregnancy stage, should be tested and considered for treatment.

Noninfectious Vaginitis

Treatment of noninfectious vaginitis should be directed at the underlying cause. Atrophic vaginitis is treated with hormonal and nonhormonal therapies. Among hormonal therapies, low-dose vaginal estrogen preparations are available in creams, tablets, and rings. Systemic estrogen therapies are also available for patients with vasomotor symptoms.67 First-line nonhormonal treatment recommendations include vaginal lubricants and moisturizers; continued sexual activity should be encouraged.68

More research is needed to better characterize the cause and treatment of inflammatory vaginitis. Some studies have demonstrated improvement in symptoms with application of topical clindamycin or steroids; however, the ideal duration of treatment and superiority of one agent over the other have not been established.35,36

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Hainer and Gibson,14 Owen and Clenney,69 and Egan and Lipsky.70

Data Sources: We searched PubMed, the Cochrane database, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse for vaginitis topics, and retrieved relevant references from review articles and clinical guidelines. Search terms included vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, Candida, and Trichomonas. We also included the literature review from Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: October 2016 and April 2017.