Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(2):453-460

A more recent article on fetal growth restriction before and after birth is available.

See related patient information handout on intrauterine growth restriction, written by the authors of this article.

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a common diagnosis in obstetrics and carries an increased risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity. Identification of IUGR is crucial because proper evaluation and management can result in a favorable outcome. Certain pregnancies are at high risk for growth restriction, although a substantial percentage of cases occur in the general obstetric population. Accurate dating early in pregnancy is essential for a diagnosis of IUGR. Ultrasound biometry is the gold standard for assessment of fetal size and the amount of amniotic fluid. Growth restriction is classified as symmetric and asymmetric. A lag in fundal height of 4 cm or more suggests IUGR. Serial ultrasonograms are important for monitoring growth restriction, and management must be individualized. General management measures include treatment of maternal disease, good nutrition and institution of bed rest. Preterm delivery is indicated if the fetus shows evidence of abnormal function on biophysical profile testing. The fetus should be monitored continuously during labor to minimize fetal hypoxia.

Fetal growth is dependent on genetic, placental and maternal factors. The fetus is thought to have an inherent growth potential that, under normal circumstances, yields a healthy newborn of appropriate size. The maternal-placental-fetal units act in harmony to provide the needs of the fetus while supporting the physiologic changes of the mother. Limitation of growth potential in the fetus is analogous to failure to thrive in the infant. The causes of both can be intrinsic or environmental.

Fetal growth restriction is the second leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality, followed only by prematurity.1,2 The incidence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is estimated to be approximately 5 percent in the general obstetric population.3 However, the incidence varies depending on the population under examination (including its geographic location) and the standard growth curves used as reference.4 In assessing perinatal outcome by weight, infants who weigh less than 2,500 g (5 lb, 8 oz) at term have a perinatal mortality rate that is five to 30 times greater than that of infants whose birth weights are at the 50th percentile.5 The mortality rate is 70 to 100 times higher in infants who weigh less than 1,500 g (3 lb, 5 oz).5 Perinatal asphyxia involving multiple organ systems is one of the most significant problems in growth-restricted infants.3

Timely diagnosis and management of IUGR is one of the major achievements in contemporary obstetrics. If the growth-restricted fetus is identified and appropriate management instituted, perinatal mortality can be reduced,6,7 underscoring the need for assessment of fetal growth at each prenatal visit.

Classification and Etiology

IUGR is the pathologic counterpart of small-for-gestational-age. The latter includes fetuses that are small but have reached their appropriate growth potential. Many babies are simply genetically small and are otherwise normal.1 Some women have a tendency to have constitutionally small babies. Although both parents' genes affect childhood growth and final adult size, maternal genes mainly influence birth weight.3,4 Parity, age and socioeconomic status are intercorrelated and may also influence the pregnancy and the infant's birth weight. Table 1 summarizes clinical situations in which IUGR may occur.

| Placental insufficiency | |

| Unexplained elevated maternal alpha-fetoprotein level | |

| Idiopathic | |

| Preeclampsia | |

| Chronic maternal disease | |

| Cardiovascular disease | |

| Diabetes | |

| Hypertension | |

| Abnormal placentation | |

| Abruptio placentae | |

| Placenta previa | |

| Infarction | |

| Circumvallate placenta | |

| Placenta accretia | |

| Hemangioma | |

| Genetic disorders | |

| Family history | |

| Trisomy 13, 18 and 21 | |

| Triploidy | |

| Turner's syndrome (some cases) | |

| Malformations | |

| Immunologic | |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | |

| Infections | |

| Cytomegalovirus | |

| Rubella | |

| Herpes | |

| Toxoplasmosis | |

| Metabolic | |

| Phenylketonuria | |

| Poor maternal nutrition | |

| Substance abuse (smoking, alcohol, drugs) | |

| Multiple gestation | |

| Low socioeconomic status | |

Unfortunately, it can be concluded that a fetus is constitutionally small only after a pathologic process has been excluded, which requires examination of the newborn. Therefore, identification of a constitutionally small infant is usually made in retrospect, after the infant is born. Constitutionally small babies are well proportioned and developmentally normal. Growth-restricted babies, however, are often malnourished or dysmorphic.

Definition of IUGR

The most widely used definition of IUGR is a fetus whose estimated weight is below the 10th percentile for its gestational age and whose abdominal circumference is below the 2.5th percentile. At term, the cutoff birth weight for IUGR is 2,500 g (5 lb, 8 oz). Growth percentiles for fetal weight versus gestational age are shown in Figure 1. Approximately 70 percent of fetuses with a birth weight below the 10th percentile for gestational age are constitutionally small8; in the remaining 30 percent, the cause of IUGR is pathologic.

Importance of Accurate Dating

Accurate dating in early pregnancy is essential for making the diagnosis of IUGR. The usual qualifier for reliable dating and establishment of an accurate gestational age is a certain date for the last menstrual period in a woman with regular cycles or assessment of gestational age by an ultrasound examination performed no later than the 20th gestational week, when the margin of error is seven to 10 days. Early ultrasound examination, ideally at eight to 13 weeks of gestation, is more accurate for estimating gestational age than ultrasound assessment later in pregnancy. Although ultrasound assessment is used later in pregnancy to estimate fetal weight, ultrasound dating is only accurate to about three weeks when it is performed at term. An error that is commonly made is to change a patient's due date on the basis of a third-trimester ultrasonogram. Doing so can result in failure to recognize IUGR.

Symmetric and Asymmetric IUGR

IUGR is usually classified as symmetric and asymmetric. Symmetric growth restriction implies a fetus whose entire body is proportionally small. Asymmetric growth restriction implies a fetus who is undernourished and is directing most of its energy to maintaining growth of vital organs, such as the brain and heart, at the expense of the liver, muscle and fat. This type of growth restriction is usually the result of placental insufficiency.

A fetus with asymmetric IUGR has a normal head dimension but a small abdominal circumference (due to decreased liver size), scrawny limbs (because of decreased muscle mass) and thinned skin (because of decreased fat). If the insult causing asymmetric growth restriction is sustained long enough or is severe enough, the fetus may lose the ability to compensate and will become symmetrically growth-restricted. Arrested head growth is of great concern to the developmental potential of the fetus.1

Diagnosis

A 22-year-old woman (gravida 1) presents to the physician who has been providing her prenatal care. Her past medical history was not significant. At the 32-week visit, her blood pressure was 140/95 mm Hg and she had gained 2.25 kg (5 lb) since her last visit. Urine dipstick testing showed 2+ protein. Fundal height was 28 cm, unchanged from the measurement obtained at the 30-week visit. The physician suspects growth restriction secondary to the onset of preeclampsia. An ultrasound examination shows a normal biparietal diameter and head circumference, although the abdominal circumference is 24.5 cm, which is at the 2.5th percentile. Estimated fetal weight is 1,465 g (3 lb, 4 oz), which places the infant in the 3rd percentile. The amniotic fluid index is 6.0 cm (less than the 2.5th percentile), confirming the diagnosis of IUGR.

The size of the uterus should be assessed at each prenatal visit. Techniques such as serial measurements of the uterine fundus are helpful in documenting continued growth if the measurements are performed by the same person. A tape measure should be used to measure the distance from the top of the pubic symphysis to the dome of the uterine fundus. This measurement, in centimeters, is normally within three weeks of the gestational age between 20 and 38 weeks of gestation. A fundal height that lags by more than 3 cm or is increasing in disparity with the gestational age may signal IUGR. A lag of 4 cm or more certainly suggests growth restriction.1 In addition, IUGR should be suspected if the maternal weight is inadequate or is decreasing.

Increased surveillance should be undertaken in patients who previously had an infant with growth restriction. A history of a previous small-for-gestational-age infant has been reported to be among the most predictive factors for subsequent IUGR. These women have up to a two- to fourfold increased risk of another similarly affected fetus.9,10

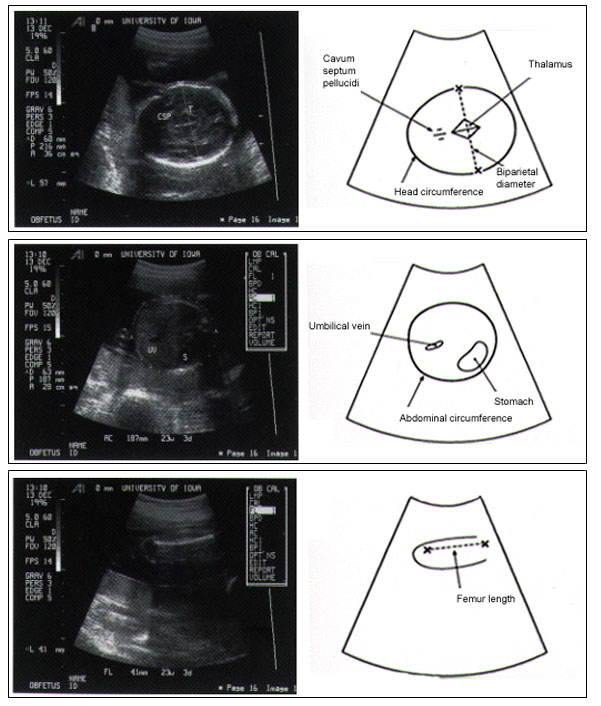

Ultrasound Biometry

Ultrasound biometry of the fetus is now the gold standard for assessing fetal growth (Figure 2). The measurements most commonly used are the biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference and femur length. Percentiles have been established for each of these parameters, and fetal weight can be calculated. The most sensitive indicator of symmetric and asymmetric IUGR is the abdominal circumference, which has a sensitivity of over 95 percent if the measurement is below the 2.5th percentile.11,12 Accurate dating of the pregnancy is essential in the use of any parameter. In the absence of reliable dating, serial scans at two-or three-week intervals must be performed to identify IUGR. It should always be remembered that each parameter measured has an error potential of about one week up to 20 gestational weeks, about two weeks from 20 to 36 weeks of gestation, and about three weeks thereafter.

Also useful is the ratio of the head circumference to the abdominal circumference (HC/AC). Between 20 and 36 weeks of gestation, the HC/AC ratio normally drops almost linearly from 1.2 to 1.0. The ratio is normal in the fetus with symmetric growth restriction and elevated in the infant with asymmetric growth restriction.

Another important use of ultrasound is estimating the amount of amniotic fluid. A decreased volume of amniotic fluid is closely associated with IUGR. Significant morbidity has been found to exist in pregnancies with an amniotic fluid index value of less than 5 cm.13 The amniotic fluid index is obtained by summing the largest cord-free vertical pocket in each of the four quadrants of an equally divided uterus. Percentiles for the amniotic fluid index at each gestational age are shown in Figure 3.14 The combination of oligohydramnios and IUGR portends a less favorable outcome, and early delivery should be considered.15,16 Generally, if the pregnancy is at 36 weeks or more, the high risk of intrauterine loss may mandate delivery.

Management

A patient presents with mild preeclampsia, and her infant demonstrates asymmetric growth restriction. A nonstress test is performed, which reveals normal reactivity. The physician tells the patient to begin bed rest. A 24-hour urine sample for protein demonstrates a level of 0.45 g (slightly elevated). Platelet count and liver function tests reveal normal values. Antenatal steroids are prescribed to promote fetal lung maturity. Daily blood pressure measurements, fetal movement profiles and biweekly nonstress tests remain normal for the next two weeks. At 34 weeks of pregnancy, the patient develops signs and symptoms of severe preeclampsia, and the decision is made to induce labor. The patient delivers a male infant weighing 1,680 g (3 lb, 11 oz), who does well in the intermediate care nursery.

The management of IUGR must be individualized for each patient. In addition to managing any maternal illness, a detailed sonogram should be performed to search for fetal anomalies, and karyotyping should be considered to rule out aneuploidy.16 Symmetric restriction may be due to a fetal chromosomal disorder or infection. This possibility should be discussed with the patient, who may decide to undergo a diagnostic procedure such as amniocentesis. It should be remembered, however, that many infants with evidence of growth restriction are constitutionally small. Serial ultrasound examinations are important to determine the severity and progression of IUGR.

A controversy involves the timing of delivery to prevent intrauterine demise because of chronic oxygen deprivation. Preterm delivery is indicated if the growth-restricted fetus demonstrates abnormal fetal function tests, and it is often advisable in the absence of demonstrable fetal growth. The risks of prematurity must be weighed against the complications unique to IUGR.4

General management measures include treatment of maternal disease, cessation of substance abuse, good nutrition and institution of bed rest. Although not of proven benefit, bed rest may maximize uterine blood flow. In any case, antenatal testing should be instituted. Options include the nonstress test, the biophysical profile and an oxytocin (Pitocin) challenge test. The biophysical profile involves assessment of fetal well-being with a combination of the nonstress test and four ultrasonographic parameters (amniotic fluid volume, respiratory movements, body movements and muscle tone). The use of Doppler flow velocimetry, usually of the umbilical artery, identifies the growth-restricted fetus at greatest risk for neonatal morbidity and mortality. In controlled trials, Doppler analysis has been associated with improved outcome,1 although it is considered experimental by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Each of these tests has a relatively high false-positive rate (i.e., 50 percent) in the low-risk patient.17

Given the high false-positive rate of non-stress tests, the significance of a nonreactive nonstress test should be further evaluated before any management decision is made. A nonreassuring nonstress test followed by assessment of the biophysical profile has been shown to lead to lower rates of intervention when compared with the oxytocin contraction test, with no impact on perinatal outcome.18

Combination testing is thought to more accurately predict the status of the fetus.17 For this reason, close antenatal surveillance is encouraged, with a well-timed delivery. A proposed management approach for IUGR is shown in Figure 4. This approach is based on outstanding advances in neonatal care and improved outcome for the low-birth-weight infant.

Labor and Delivery

Because of the increased risk of intrapartum asphyxia, the fetus should be monitored carefully and continuously during labor.19,20 Delivery should be in a hospital capable of dealing with the various neonatal morbidities associated with growth restriction, including asphyxia, meconium aspiration, sepsis, hypoglycemia and malformations. Preterm induction of labor is often required. Amnioinfusion may be of benefit in the presence of a nonreassuring fetal response during labor and a low amniotic fluid index or oligohydramnios. In the face of deteriorating fetal status, a cesarean section should be performed.

In subsequent pregnancies, the use of low-dose aspirin may be of benefit in reducing the incidence of IUGR in selected high-risk women. While the results of a recent meta-analysis showed that early aspirin treatment reduced the risk of IUGR, routine use of aspirin in pregnancy is not advocated.21

Outcome

Most infants who had growth restriction in utero have normal rates of growth in infancy and childhood, although studies have demonstrated that at least one third of them never achieve normal height.22 Many of these infants also are born prematurely, with its similar, albeit independent, morbidities. The lower the birth weight and the earlier the gestational age, the less the child's chance of catching up. Neurologic development is also related to the degree of growth restriction and prematurity.23 Decreased intrauterine growth may possibly have a negative effect on brain growth and mental developmental potential.24 At baseline, children with a history of IUGR have been found to demonstrate attention and performance deficits.25 Minimizing hypoxic episodes during labor and delivery, as well as optimizing neonatal care for these infants, will likely produce the healthiest outcome.