Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(11):2433-2444

A more recent article on urinary incontinence in women is available.

See related patient information handouts on urinary incontinence and pelvic muscle exercises, written by the authors of this article.

Because the prevalence of urinary incontinence increases with age, a working knowledge of the diagnosis and treatment of the various types of urinary incontinence is fundamental to the care of women. As the population of the United States ages, primary care physicians can expect to see an increasing number of patients with urinary incontinence. By obtaining a careful medical history and performing a comprehensive physical examination, the primary care physician can initiate successful treatment for the majority of patients without the need for invasive testing. This article offers a comprehensive approach to the evaluation and management of urinary incontinence in women.

Urinary incontinence is an underdiagnosed and underreported condition with major economic and psychosocial effects on society. The direct cost of treating urinary incontinence in men and women of all ages was estimated at $26.3 billion in 1995.1

The reported incidence of urinary incontinence varies considerably depending on the age of the study population, the study methods and the definition of the problem. A questionnaire study2 that included women between the ages of 20 to 80 years, reported an overall prevalence for urinary incontinence of 53.2 percent. Even in younger women (between 20 to 49 years of age), the prevalence was 47 percent. In another study3 involving 2,763 postmenopausal women (mean age: 67 years), 56 percent reported urinary incontinence at least weekly.

Despite the high prevalence of urinary incontinence, fewer than one half of community-dwelling persons with urinary incontinence consult physicians about the problem.4 This article describes a comprehensive approach to the evaluation and management of urinary incontinence in women.

Types of Urinary Incontinence

The key to accurate diagnosis of urinary incontinence is consideration of all possible causes during the initial assessment. Most cases of urinary incontinence fall under one of the following six major subtypes: stress incontinence, overactive bladder, mixed incontinence, overflow incontinence, lack of continuity or deformity, or functional incontinence.

STRESS INCONTINENCE

Stress incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine during an increase of intra-abdominal pressure produced from activities such as coughing, laughing or exercising. The underlying abnormality is typically urethral hypermobility caused by a failure of the normal anatomic supports of the urethrovesical junction (or bladder neck). Normally, increased intra-abdominal pressure is transmitted evenly across the bladder body and neck, but when poor anatomic support allows the bladder neck to be displaced outside the abdominal cavity during such activities as coughing or laughing, a disproportionate rise in bladder pressure over urethral pressure results in urine loss. Loss of bladder neck support is often attributed to nerve, muscle and connective tissue injury occurring during vaginal delivery5; however, vaginal childbirth is certainly not the only contributing factor.

The lack of normal intrinsic pressure within the urethra—known as intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency—is another factor leading to stress incontinence. Advanced age, inadequate estrogen levels, previous vaginal surgery and certain neurologic lesions are associated with poor urethral sphincter function. The diagnosis is made by a combination of assessing the severity of leakage and conducting specialized tests such as urodynamics and cystourethroscopy.

OVERACTIVE BLADDER

Involuntary loss of urine preceded by a strong urge to void, whether or not the bladder is full, is a symptom of the condition commonly referred to as “urge incontinence.” To expand the number and types of patients eligible for clinical trials, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) adopted the term “overactive bladder” to describe a clinical syndrome that includes not only urge incontinence, but urgency, frequency, dysuria and nocturia as well. Other commonly used terms such as detrusor instability and detrusor hyperreflexia refer to involuntary detrusor contractions observed during urodynamic studies.

In this article, the term overactive bladder will be used in place of the terms urge incontinence, detrusor instability or detrusor hyperreflexia. Some cases of overactive bladder can be attributed to specific conditions, such as acute or chronic urinary tract infection, bladder cancer and bladder stones, but most cases result from an idiopathic inability to suppress detrusor contractions. While simple or complex urodynamic studies may be performed to make the definitive diagnosis of detrusor instability or detrusor hyperreflexia, most patients may be treated without undergoing invasive testing.

MIXED INCONTINENCE

Women with genuine stress incontinence and overactive bladder are said to have mixed incontinence. For these patients, it is helpful to identify the most bothersome symptom and treat accordingly.

OVERFLOW INCONTINENCE

Overflow incontinence is urine loss associated with overdistension of the bladder. Patients can present with frequent or constant dribbling, overactive bladder or stress incontinence. Overdistension is typically caused by an underactive bladder (detrusor) muscle and/or outlet obstruction. The detrusor muscle may be underactive secondary to drug therapy (especially with psychotropic medications) or conditions such as diabetic neuropathy, low spinal cord injury, radical pelvic surgery and multiple sclerosis. Outlet obstruction in women is almost always a result of urethral occlusion from pelvic organ prolapse or previous anti-incontinence surgery.

LACK OF CONTINUITY OR DEFORMITY

The most common cause of incontinence in this category is a fistula. In developed countries, vesicovaginal or ureterovaginal fistulas typically arise as complications of hysterectomy or other pelvic surgery.6 Patients with other abnormalities such as ectopic ureters and diverticulae can also present with incontinence.

FUNCTIONAL INCONTINENCE

Women with urinary incontinence caused by chronic impairment of physical or cognitive function, or both, are said to have functional incontinence. These patients have overactive bladder relative to the ability or speed with which they can get to the toilet. Because many functionally impaired persons can also have other types of urinary incontinence that may respond to specific treatments, pure functional incontinence should be a diagnosis of exclusion.

History and Physical Examination

A preliminary diagnosis of urinary incontinence can be made on the basis of a history, physical examination and a few simple office and laboratory tests. Initial therapy may be based on these findings. If complex conditions are present or if initial treatments are unsuccessful, definitive specialized studies are required. Because urinary incontinence is a common condition, patients being examined for another problem may mention episodes of urinary incontinence. For instance, patients presenting with cold symptoms may remark that every time they cough, they “leak” urine. Rather than attempt a complete evaluation for urinary incontinence during that visit, the physician can ask a few simple screening questions.

Table 1 lists a few key questions that can provide information on the severity of urinary incontinence and help distinguish the major subtypes. If the patient answers affirmatively to these screening questions, a 24-hour “bladder diary” can be given to the patient to complete (Figure 1). The diary entries can then be reviewed at a subsequent office visit. An algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence is provided in Figure 2.

| Do you leak urine when you cough, laugh, lift something or sneeze? How often?* |

| Do you ever leak urine when you have a strong urge on the way to the bathroom? How often?† |

| How frequently do you empty your bladder during the day?† |

| How many times do you get up to urinate after going to sleep? Is it the urge to urinate that wakes you?† |

| Do you ever leak urine during sex?† |

| Do you wear pads that protect you from leaking urine? How often do you have to change them?‡ |

| Do you ever find urine on your pads or clothes and were unaware of when the leakage occurred?‡ |

| Does it hurt when you urinate?§ |

| Do you ever feel that you are unable to completely empty your bladder?§ |

HISTORY

The medical history should also identify such contributing factors as diabetes, stroke, lumbar disc disease, chronic lung disease, fecal impaction and cognitive impairment. The obstetric and gynecologic history should include gravity; parity; the number of vaginal, instrument-assisted and cesarean deliveries; the time interval between deliveries; previous hysterectomy and/or vaginal or bladder surgery; pelvic radiotherapy; trauma; and estrogen status.

Because fecal impaction has been linked to urinary incontinence,7 a history that includes frequency of bowel movements, length of time to evacuate and whether the patient must splint her vagina or perineum during defecation should be obtained. Patients should also be questioned about fecal incontinence. Patients are even more reluctant to discuss fecal incontinence than urinary incontinence; thus, direct questioning is essential. Further discussion of the evaluation and management of fecal incontinence is beyond the scope of this article.

A complete list of all prescription and non-prescription drugs that the patient is taking should be obtained. Table 2 lists drugs that significantly affect continence. When appropriate, discontinuation of these medications or substitution of appropriate alternative medications will often cure or significantly improve urinary incontinence.

| Drug | Side effect |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants, antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics | Sedation, retention (overflow) |

| Diuretics | Frequency, urgency (OAB) |

| Caffeine | Frequency, urgency (OAB) |

| Anticholinergics | Retention (overflow) |

| Alcohol | Sedation, frequency (OAB) |

| Narcotics | Retention, constipation, sedation (OAB and overflow) |

| Alpha-adrenergic blockers | Decreased urethral tone (stress incontinence) |

| Alpha-adrenergic agonists | Increased urethral tone, retention (overflow) |

| Beta-adrenergic agonists | Inhibited detrusor function, retention (overflow) |

| Calcium channel blockers | Retention (overflow) |

| ACE inhibitors | Cough (stress incontinence) |

BLADDER DIARY

The 24-hour bladder diary can provide an accurate record of urinary output, average voided volume, frequency of voiding, and frequency and nature of incontinent episodes, as well as type and volume of fluid intake. Patients are asked to catch and measure their urine output in a measuring cup during any “normal” 24-hour period they choose. Occasionally, disorders such as diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus or excessive caffeine intake, can be discovered through the bladder diary entries.

The diary enables the physician to make helpful suggestions regarding the type and amount of fluid intake. For example, many women with lower urinary tract dysfunction believe they should drink eight to 10 large glasses of water per day, thus maintaining an almost constantly full bladder. Such patients will often benefit from being given “permission” by their physician to just drink when they are thirsty. Patients with significant nocturia may benefit from decreasing fluid intake after their evening meal.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Immediately before the physical examination, the patient should void as normally and completely as possible. The voided volume should be recorded. A post-void residual volume can then be determined within 10 minutes by catheterization or ultrasound examination. Post-void residual volumes consistently measuring more than 100 mL are considered abnormal. The advantage of using a catheter to determine the post-void residual volume is that a reliably clean urine sample can be sent for culture and urinalysis.

While the need to determine post-void residual volume in a primary care practice is somewhat controversial, doing so allows screening for overflow incontinence, as well as for conditions such as chronic urinary tract infections, hematuria, diabetes, kidney disease and metabolic abnormalities.

The abdominal examination should rule out diastasis recti, masses, ascites and organomegaly, which can influence intra-abdominal pressure and urinary tract function. Pulmonary and cardiovascular assessment may be indicated to assess control of cough or the need for medications such as diuretics.

The lumbosacral nerve roots should be assessed by checking deep tendon reflexes, lower extremity strength, sharp/dull sensation and the bulbocavernosus and clitoral sacral reflexes (Figure 3). Abnormal findings such as deep tendon hyperreflexia or absence of the bulbocavernosus reflex should alert the physician to possible underlying neurologic lesions contributing to urinary incontinence.

The pelvic examination should include an evaluation for inflammation, infection and atrophy. Such conditions can increase afferent sensation and thereby cause urinary urgency, frequency, dysuria and overactive bladder. Because the urethra and trigone are estrogen-dependent tissues, estrogen deficiency can contribute to urinary incontinence and urinary dysfunction.8 The most common signs of inadequate estrogen levels are thinning and paleness of the vaginal epithelium, loss of rugae, disappearance of the labia minora and presence of a urethral caruncle.

A urethral diverticula is usually identified as a distal bulge under the urethra. Gentle massage of the area will frequently produce a purulent discharge from the urethral meatus.

Stress incontinence may be objectively demonstrated before initiating treatment. Testing for stress incontinence is performed by asking the patient to cough vigorously while the examiner watches for leakage of urine. Women who demonstrate urine leakage in the supine position with the bladder relatively empty (i.e., soon after determining post-void residual volume) are at increased risk of having a severe form of stress incontinence known as intrinsic sphincter deficiency,9 possibly making treatment by conservative measures difficult.

While performing the bimanual examination, levator ani muscle function can be evaluated by asking the patient to tighten her “vaginal muscles” and hold the contraction as long as possible. It is normal for a woman to be able to hold such a contraction for five to 10 seconds. Very weak or absent voluntary levator ani muscle contractions are an indication that biofeedback training sessions with a pelvic floor physical therapist may be necessary. The bimanual examination should also include a rectal examination to check anal sphincter tone and, for fecal impaction, the presence of occult blood or rectal lesions.

Finally, vaginal discharge can mimic urinary incontinence, especially in obese patients. In differentiating between vaginal discharge versus urinary incontinence, a phenazopyridine (Pyridium) test may be performed. A single oral dose of phenazopyridine will turn a patient's urine bright orange. She can then be asked to wear a pad and perform provocative maneuvers that would normally result in “urine loss.” True urine loss will stain the pad orange, while a vaginal discharge should not.

Treatment

After obtaining a complete history and performing a physical examination, it is appropriate to initiate treatment without referral for specialized testing in most cases. This section will address treatment of the two most common types of urinary incontinence: stress incontinence and overactive bladder. Treatment of overflow incontinence and functional incontinence should be directed at the underlying condition producing these conditions. Treatment of women with urinary incontinence secondary to a urinary or gynecologic deformity or lack of continuity usually involves surgery by a urogynecologist or a urologist.

STRESS INCONTINENCE

Rehabilitation of the pelvic floor muscles is the common goal of treatments through the use of pelvic muscle exercises (also known as Kegel's exercises), weighted vaginal cones and pelvic floor electrical stimulation. These treatments are believed to increase the resting tension, contractile force and recruitment speed of the voluntary sphincter component of the pelvic diaphragm. Up to 38 percent of motivated patients who follow the exercise regimen (provided as a patient education handout) for at least three months will experience a cure of pure stress incontinence.10 Careful supervision produces a dramatic difference in the degree of success that can be achieved.11

Pelvic floor electrical stimulation with a vaginal or anal probe produces a contraction of the levator ani muscle. Many third-party payers refuse to pay for this procedure despite results of a placebo-controlled, randomized study13 indicating cure or improvement in 48 percent of treated patients, compared with 13 percent of control subjects.

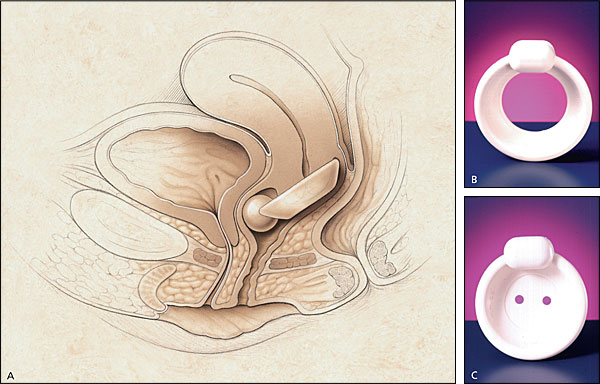

Occlusive devices, such as pessaries, can mimic the effects of a retropubic urethropexy (Figure 5). A properly fitted pessary prevents urine loss during vigorous coughing in the standing position with a full bladder. The patient should be able to comfortably insert and remove the pessary, and it should not cause voiding dysfunction. Other types of occlusive devices include urethral plugging or stenting. Thus far, no urethral plug or stent has become widely accepted by women, and many of these devices have been removed from the market because of the lack of acceptance.

Medications such as estrogens and alpha-adrenergic drugs may also be effective in treating women with stress incontinence (Table 3). The presence of estrogen receptors in high concentrations throughout the lower urinary tract14 makes it possible to treat women with stress incontinence by localized estrogen replacement therapy (ERT). ERT causes engorgement of the periurethral blood supply and subsequent thickening of the urethral mucosa.15 Localized ERT can be given in the form of estrogen cream or an estradiol-impregnated vaginal ring (Estring).

| Drug | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Stress incontinence | |

| Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) | 15 to 30 mg, three times daily |

| Vaginal estrogen ring (Estring) | Insert into vagina every three months. |

| Vaginal estrogen cream | 0.5 to 1 g, apply in vagina every night. |

| Overactive bladder | |

| Oxybutynin ER (Ditropan XL) | 5 to 15 mg, every morning |

| Generic oxybutynin | 2.5 to 10 mg, two to four times daily |

| Tolterodine (Detrol) | 1 to 2 mg, two times daily |

| Imipramine (Tofranil) | 10 to 75 mg, every night |

| Dicyclomine (Bentyl) | 10 to 20 mg, four times daily |

| Hyoscyamine (Cystospaz) | 0.375 mg, two times daily |

Alpha-adrenergic drugs such as pseudoephedrine are believed to improve the symptoms of stress incontinence by increasing resting urethral tone. These drugs cause subjective improvement in 20 to 60 percent of patients.16

Surgery to correct genuine stress incontinence is a viable option for most patients. Retropubic urethropexies (i.e., Burch laparoscopic and Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz [MMK] procedures) and suburethral slings have long-term success rates consistently reported in the 80 to 96 percent range and are clearly superior to other procedures.17

A new minimally invasive suburethral sling (“tension-free vaginal tape”) has been shown to cause less postoperative morbidity than traditional surgeries while achieving long-term (five-year) cure rates greater than 86 percent.18 The sling is placed during surgery under local anesthesia on an outpatient basis. While the tension-free vaginal tape sling is a nonabsorbable polypropylene mesh, and concern may exist regarding erosion and/or infection of this material; to date, no such cases have been reported.

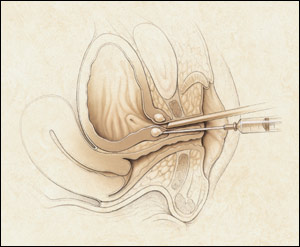

Another minimally invasive procedure for the treatment of stress incontinence is periurethral injection (Figure 6). This procedure involves injection of material at the bladder neck just under the urothelium and is performed in an office setting under local anesthesia. Currently, two devices, both injectable debulking agents, have been labeled by the FDA for the treatment of stress incontinence by periurethral injection: glutaraldehyde cross-linked bovine collagen (Contigen Bard Collagen Implant, C.R. Bard, Inc., Covington, Ga.), and carbon-coated beads (Durasphere, Advanced Uroscience, Inc., St. Paul, Minn.). Both of these devices typically require multiple treatment sessions to achieve cure.

OVERACTIVE BLADDER

Behavioral therapy, in the form of bladder retraining and biofeedback, seeks to reestablish cortical control of the bladder by having the patient ignore urgency and void only in response to cortical signals during waking hours. In one controlled trial,19 75 percent of patients using the technique reported at least a 50 percent decrease in the number of incontinent episodes; 20 percent reported complete dryness. Specific instructions on this type of therapy may be found in the resources listed in the patient education handout.

Because of their large therapeutic index, pharmacologic agents may be given empirically to women with symptoms of overactive bladder. Two new medications, tolterodine (Detrol) and extended-release oxybutynin chloride (Ditropan XL), have largely replaced generic oxybutynin as a first-line treatment option for overactive bladder because of favorable side effect profiles. Table 3 lists the most common medications used to treat women with overactive bladder. It is important for patients to understand that there may be a “trial and error” process involved in finding an effective drug and dosage.

As with stress incontinence, ERT is also an effective treatment for women with overactive bladder. Even in patients taking systemic estrogen, localized ERT (i.e., estradiol-impregnated vaginal ring) may increase inadequate estrogen levels and decrease the symptoms associated with overactive bladder.

Likewise, pelvic floor electrical stimulation is also effective in treating women with overactive bladder. Results of one prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial20 revealed that pelvic floor electrical stimulation resulted in a 50 percent cure rate of detrusor instability. This procedure is widely used in Europe, but acceptance has been slower in the United States.

Neuromodulation of the sacral nerve roots through electrodes implanted in the sacral foramina (Interstim, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, Minn.) is a promising new surgical treatment that has been found to be effective in the treatment of urge incontinence, urgency/frequency syndrome, urinary retention and even pelvic pain.21,22 Patients first undergo implantation of a temporary test stimulator. If a significant reduction in symptoms occurs, the permanent device is implanted one week later. Given the cost and invasive nature of this modality, it should be reserved for patients who do not respond to more conservative options.

The FDA has recently approved extracorporeal magnetic innervation (NeoControl Pelvic Floor Therapy System, Neotonus Inc., Marietta, Ga.), a noninvasive procedure for the treatment of incontinence caused by pelvic floor weakness. The patient sits fully clothed in a pulsating magnetic chair that stimulates the pelvic floor. A typical treatment session lasts approximately 20 minutes and includes high- and low-frequency stimulation. Preliminary results from one uncontrolled trial23 suggest that extracorporeal magnetic innervation may have a place in the treatment of women with both stress and urge incontinence.