Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(9):1776-1783

Patient information: See related handout on nasopharyngeal cancer, written by the author of this article.

Because of a documented increased incidence, nasopharyngeal cancer should be considered when signs or symptoms of ear, nose and throat disease are present in patients from southern China (in particular, Hong Kong and the province of Guangdong) or Southeast Asia. Environmental factors, the Epstein-Barr virus and genetic factors have been associated with the development of nasopharyngeal cancer. Patients with this malignancy most often present with a cervical mass from metastatic spread to a lymph node. Other possible presentations include ipsilateral serous otitis, hearing loss, nasal obstruction, frank epistaxis, purulent or bloody rhinorrhea, and facial neuropathy or facial nerve palsies. Radiotherapy is often curative. The addition of chemotherapy has produced high response rates in local and regionally advanced disease.

Although nasopharyngeal cancer is rare in the general U.S. population, it is significantly more likely to occur in refugees from Southeast Asia who have come to the United States in the past 25 years. Once diagnosed, the malignancy has great potential for cure. This article provides a brief overview of nasopharyngeal cancer, with emphasis on its occurrence in patients from Southeast Asia.

Illustrative Case

A 47-year-old Hmong man presented to his family physician with bloody rhinorrhea, epistaxis, right-sided hearing loss and headache of two weeks' duration. (The Hmong, also known as the Miao or Meo, are mountain-dwelling peoples of China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand.) The patient's medical history was remarkable for colon cancer at 36 years of age, which evidently responded to Hmong therapies (nonsurgical). There was no family history of cancer. The patient had never smoked; he used alcohol rarely and did not use illicit drugs. The patient's family had fled from Laos to the United States in the mid-1970s.

The review of systems was remarkable only for fatigue in the previous few weeks. The physical examination revealed right middle ear effusion, right hemifacial and periauricular hyperesthesia, and a trace of mucoid, bloody discharge in the nares. Neither cervical nor clavicular adenopathy was present.

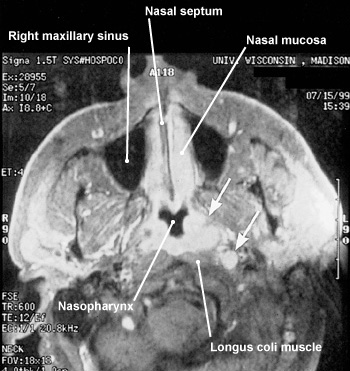

Subsequent endoscopic biopsy of the right nasopharynx demonstrated mixed keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a right nasopharyngeal mass with erosion into the sphenoid sinus.

Nasopharyngeal cancer was diagnosed and determined to be stage III (T3 N0: tumor invasion into the bony structures and/or paranasal sinuses; no regional lymph node metastasis). The patient underwent concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy; he experienced postirradiation headache and facial neuropathy. One year later, follow-up MRI studies showed nearly complete tumor regression.

Epidemiology

Nasopharyngeal cancer accounts for fewer than 1 percent of malignancies in North America, western Europe and Japan, with incidence rates of one to one and one-half cases per 100,000 population per year.1 This malignancy has an intermediate incidence of five to nine cases per 100,000 population per year in inhabitants of northern China, the Mediterranean basin (southern Italy, Greece and Turkey), North Africa and Southeast Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore), and in persons of southern Chinese heritage who were born in the West (Australia, Hawaii and California). Among the Inuit in Alaska and Greenland, the incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer is increased to 15 to 20 cases per 100,000 population per year.1,2

In southern China, particularly Hong Kong and Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton, and the capital of the province of Guangdong), nasopharyngeal cancer has a much higher incidence, with documented rates of 10 to 150 cases per 100,000 population per year (Table 1).1,2 Indeed, this malignancy is often referred to as “Cantonese cancer” or ”Kwangtung tumor.”1 (Kwangtung is the old name for Guangdong, the province in which Guangzhou is located.)

| Geographic area | Average number (range) of cases per 100,000 population per year | Average percentage of total cases per year |

|---|---|---|

| Southern China (particularly Hong Kong and Guangzhou [formerly Canton])* | 80 (10 to 150) | 61 |

| Alaska and Greenland | 18 (15 to 20) | 13 |

| Northern China | 7 (5 to 9) | 5 |

| Mediterranean basin (southern Italy, Greece and Turkey) | 7 (5 to 9) | 5 |

| North Africa | 7 (5 to 9) | 5 |

| Southeast Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore) | 7 (5 to 9) | 5 |

| North America, western Europe and Japan | 1 (1 to 1.5) | 1 |

Etiology and Pathogenesis

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

The consumption of salted fish and other salt-preserved foods, including eggs, leafy vegetables and roots, in early childhood has been documented as a substantial risk factor for the development of nasopharyngeal cancer in Malaysian Chinese.3 Similarly, salted-fish consumption in early childhood has been correlated with an unusually high incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer in the boat communities of Hong Kong's harbors.1 N-nitro-sodimethylamine in salted fish, perhaps in combination with vitamin deficiency, has been considered a likely carcinogen.1,3

EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS

Epstein-Barr virus, a herpesvirus, is the causative agent in acute infectious mononucleosis and is also associated with Hodgkin's disease, Burkitt's lymphoma, lymphoproliferative disease in the post-transplant setting, and T-cell lymphoma.1,2 Epstein-Barr virus initiates an early active (or lytic) infection; the virus then persists in a latent state until it is reactivated under certain conditions of immunosuppression or illness.

The link between nasopharyngeal cancer and Epstein-Barr virus was first observed in 1966, when the sera of patients with the malignancy were found to manifest precipitating antibodies against cells infected with the virus.7 Subsequent studies have described elevated levels of IgG and IgA antibodies directed against particular components of Epstein-Barr virus in patients with nasopharyngeal cancer.1,2

GENETIC SUSCEPTIBILITY

Genetic susceptibility has also been proposed as a risk factor for the development of nasopharyngeal cancer. Haplotypes that have been associated with the malignancy include certain human leukocyte antigens (HLA), including HLA-A2, HLA-B46 and HLA-B58.8

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A thorough history and a complete physical examination are essential in patients with ear, nose and throat complaints, especially patients from populations with an increased incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer.

Most often, patients with nasopharyngeal cancer present with a cervical mass from metastatic spread to a lymph node. Another common presenting sign is unilateral serous otitis as a result of eustachian tube occlusion by the primary tumor.2 In some instances, digital examination in patients who have received a general anesthetic may localize a nodular lesion in the region of the eustachian tube orifice. Such tumors are often difficult to discern, however, as they can be small.

The presentation may also include nasal obstruction, frank epistaxis or purulent, bloody rhinorrhea, hearing loss (which may be temporarily relieved with autoinsufflation), tinnitus or headache. Patients with nasopharyngeal cancer may report facial hyperesthesia, paresthesia or dysesthesia, sometimes in the distribution of the second and third divisions of the trigeminal nerve. Cranial nerve infiltration with resultant palsy may also be present.2,9

The differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal cancer includes other nasopharyngeal or sinusal masses (e.g., lymphoma, including Hodgkin's disease and lethal midline reticulosis), Wegener's granulomatosis and mucocele.

ENDOSCOPY

Further definition of the lesion or direct visualization of a nonpalpable but suspected lesion is possible with indirect nasopharyngoscopy or fiberoptic flexible or rigid endoscopy. Moreover, endoscopy allows a biopsy to be performed.9 Endoscopy is felt to be essential to the work-up for nasopharyngeal cancer.

LABORATORY STUDIES

Although serologic testing for Epstein-Barr virus is not a diagnostic tool for nasopharyngeal cancer, it may be beneficial in some patients. Fine-needle aspiration and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to identify Epstein-Barr virus genomes may be useful in patients who have cervical adenopathy but no discernible primary lesion.10–12

Tumor Assessment and Staging

TUMOR IMAGING

TUMOR EXTENSION

Structures adjacent to the nasopharynx, such as nerves and vessels, facilitate the infiltration of nasopharyngeal cancer through foramina and fissures, from extracranial to intracranial spaces. Another mechanism of disease extension is direct invasion into the bone.1,9 Consequently, recognition of advanced disease is based on the degree of derangement of nasopharyngeal anatomy by the tumor mass, as well as the extent of tumor infiltration into surrounding tissue (Table 2).15

STAGING

The American Joint Committee on Cancer and the International Union Against Cancer have developed staging systems for primary lesions based on the region of the nasopharynx that is involved.1,9,19 One investigator20 developed another system for staging cervical metastases; this system has been adopted primarily in Hong Kong.

Treatment

Nasopharyngeal cancer has traditionally been treated with full-course radiotherapy. After appropriate radiotherapy, only about 10 to 20 percent of patient deaths are caused by local treatment failure.1 Treatment results are more favorable in early stage disease.

Recent studies have demonstrated that concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy are effective in the treatment of local and regionally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer.14,16 In one study21 of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for patients with early stage (stage I and stage II) nasopharyngeal cancer, consistently high survival rates were documented. In this study, patients with stage I disease were treated with radiotherapy alone while patients with stage II disease received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Three-year disease-free survival rates were 91.7 percent for those with stage I disease and 96.9 percent for those with stage II disease.

Late-stage nasopharyngeal cancer (stage III and stage IV) demonstrated a three-year overall survival rate of 93 percent in another study22 of concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In this study, all patients received concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Final Comments

Since the mid-1970s, hundreds of thousands of refugees from Southeast Asia have been granted admittance to the United States as a direct result of their alliance with this country during the Vietnam War. These refugees constitute numerous groups, including, but not limited to, Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians, as well as a host of ethnic subgroups such as the Hmong.

Subsequent studies undertaken in the United States have developed data on the incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer in persons of Chinese origin and persons of Southeast Asian (non-Chinese) heritage.25–27 These data seem to correlate with results from previous studies. However, specific Southeast Asian ethnic subgroups (the Hmong, Karen and Akha, to name only three) are not well defined in the studies.

One possible explanation for this lack of data is that many Southeast Asian ethnic groups are reluctant to seek Western health care. Obviously, diseases are not reportable if patients do not volunteer complaints or do not allow themselves to be identified as ill. For the Hmong in particular, gruesome myths of torture and cannibalism at the hands of “American” physicians perpetuate a mentality of mistrust founded on misinformation and suspicion.

In addition, cancer registries and surveillance systems to date have been unable to further stratify “Asian/Pacific Islander” adequately. This could result in underreporting and, thus, underrepresentation of Southeast Asian ethnic subgroups that may be vulnerable to nasopharyngeal cancer.

Although many Southeast Asian ethnic groups claim genetic distinction from the Chinese and consequently may have less genetic susceptibility to nasopharyngeal cancer, the distinct possibility remains that environmental and virologic exposure among these ethnic groups mirror those of their southern Chinese neighbors. The relative proximity of Southeast Asia to southern China may have afforded similar exposures. Commercial and cultural interchanges (including intermarriage) within this shared geography may have resulted in exposure to similar insults (carcinogens and viruses).

It is important for family physicians to be aware of the possibility of nasopharyngeal cancer in Asians of Chinese heritage. Furthermore, although many Southeast Asian ethnic groups claim no genetic commonality with the Chinese, it is advisable to consider these groups to be at risk of nasopharyngeal cancer.