A more recent article on common skin conditions during pregnancy is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(2):211-218

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Common skin conditions during pregnancy generally can be separated into three categories: hormone-related, preexisting, and pregnancy-specific. Normal hormone changes during pregnancy may cause benign skin conditions including striae gravidarum (stretch marks); hyper-pigmentation (e.g., melasma); and hair, nail, and vascular changes. Preexisting skin conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, fungal infections, cutaneous tumors) may change during pregnancy. Pregnancy-specific skin conditions include pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, prurigo of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, impetigo herpetiformis, and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy are the most common of these disorders. Most skin conditions resolve postpartum and only require symptomatic treatment. However, there are specific treatments for some conditions (e.g., melasma, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy). Antepartum surveillance is recommended for patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, and pemphigoid gestationis.

There are three general categories of pregnancy-associated skin conditions: (1) benign skin conditions from normal hormonal changes, (2) preexisting skin conditions that change during pregnancy, and (3) pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Some conditions may overlap categories.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| High-potency, broad-spectrum (ultraviolet A and B) sunscreens may prevent melasma. | C | 1, 2 |

| Severe epidermal melasma may be treated postpartum with combinations of topical tretinoin (Retin-A), hydroquinone (Eldoquin Forte), and corticosteroids. | B | 9, 10 |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) effectively reduces pruritus and serum bile acid levels in patients with severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. | B | 18, 27 |

| Patients with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, impetigo herpetiformis, and pemphigoid gestationis should receive antepartum surveillance. | C | 18, 22 |

Benign Skin Changes

Skin conditions caused by normal hormonal changes during pregnancy include striae gravidarum; hyperpigmentation; and hair, nail, and vascular changes.

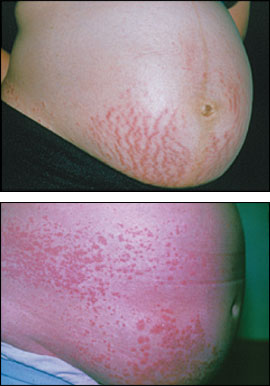

STRIAE GRAVIDARUM

Striae gravidarum (stretch marks) occur in up to 90 percent of pregnant women by the third trimester (Figure 1).1,2 Striae appear as pink-purple, atrophic lines or bands on the abdomen, buttocks, breasts, thighs, or arms. They are more common in younger women, women with larger babies, and women with higher body mass indices.3 Nonwhites and women with a history of breast or thigh striae or a family history of striae gravidarum also are at higher risk.4 The cause of striae is multifactorial and includes physical factors (e.g., actual stretching of the skin) and hormonal factors (e.g., effects of adrenocortical steroids, estrogen, and relaxin on the skin's elastic fibers).

Numerous creams, emollients, and oils (e.g., vitamin E cream, cocoa butter, aloe vera lotion, olive oil) are used to prevent striae; however, there is no evidence that these treatments are effective. Limited evidence suggests that two topical treatments may help prevent striae.5 One contains Centella asiatica extract plus alpha-tocopherol and collagen-elastin hydrolysates. The other treatment contains tocopherol, essential fatty acids, panthenol, hyaluronic acid, elastin, and menthol. However, neither of these products is widely available, and the safety of using Centella asiatica during pregnancy and the components responsible for their effectiveness are unclear.6 Further studies are needed before these treatments and commonly used creams and emollients can be recommended for widespread use.

Most striae fade to pale- or flesh-colored lines and shrink postpartum, although they usually do not disappear completely. Treatment is nonspecific, and a limited evidence base exists. Postpartum treatments include topical tretinoin (Retin-A) or oral tretinoin (Vesanoid) therapy (U.S. Food and Drug Administration pregnancy categories C and D, respectively; unknown safety in breast-feeding women) and laser treatment (585 nm, pulsed dye laser).7,8

HYPERPIGMENTATION

Nearly all women experience some degree of hyperpigmentation during pregnancy. These changes usually are more pronounced in women with a darker complexion. The areolae, axillae, and genitals are most commonly affected, although scars and nevi also may darken. The linea nigra is the line that often forms when the abdominal linea alba darkens during pregnancy.

Exposure to sunlight and other ultraviolet radiation worsens melasma; therefore, using high-potency, broad-spectrum (ultraviolet A and B) sunscreens and avoiding excessive exposure to sunlight may prevent melasma from developing or being exacerbated.1,2 Although no specific treatments are indicated during pregnancy, physicians can reassure patients that melasma resolves postpartum in most cases. However, it may not resolve fully and may recur with future pregnancies or with oral contraceptive use.1,2 Severe postpartum epidermal melasma typically is treated with combinations of topical tretinoin, hydroquinone (Eldoquin Forte), and corticosteroids.9,10

HAIR AND NAIL CHANGES

An increase or decrease in growth and production of hair is common during pregnancy.1,2,11 Many women experience some degree of hirsutism on the face, limbs, and back caused by endocrine changes during pregnancy. Hirsutism generally resolves postpartum, although cosmetic removal may be considered if the condition persists. Pregnant women also may notice mild thickening of scalp hair. This is caused by a prolonged active (anagen) phase of hair growth. Postpartum, scalp hair enters a prolonged resting (telogen) phase of hair growth, causing increased shedding (telogen effluvium), which may last for several months or more than one year after pregnancy.12 A few women with a tendency toward androgenetic alopecia may notice frontoparietal hair loss, which may not resolve after pregnancy.

VASCULAR CHANGES

Normal changes in estrogen production during pregnancy can cause dilation, instability, proliferation, and congestion of blood vessels. Most of these vascular changes regress postpartum.1 Spider telangiectasias (spider nevi or spider angiomas) occur in about two thirds of light-complected and 10 percent of dark-complected pregnant women, primarily appearing on the face, neck, and arms. The condition is most common during the first and second trimesters.1,2,11 Palmar erythema occurs in about two thirds of light-complected and up to one third of dark-complected pregnant women. Saphenous, vulvar, or hemorrhoidal varicosities occur in about 40 percent of pregnant women.1,2,11

Vascular changes coupled with increased blood volume can cause increased “leakage,” which leads to nonpitting edema of the face, eyelids, and extremities in up to one half of pregnant women.1,11 Increased blood flow and instability of pelvic vessels may cause vaginal erythema (Chadwick's sign) and a bluish discoloration of the cervix (Goodell's sign).1 Vasomotor instability also may cause facial flushing; dermatographism; hot and cold sensations; and marble skin, a condition characterized by bluish skin discoloration from an exaggerated response to cold.2

All pregnant women experience some gingival hyperemia and edema, which may be associated with gingivitis and bleeding, especially in the third trimester.1,11 Pyogenic granulomas can appear late in the first trimester or in the second trimester as deep red or purple nodules on the gingivae or, less commonly, on other skin surfaces. Observation is appropriate in most patients because these lesions typically regress post-partum. However, prompt consultation and possible excision may be indicated if bleeding occurs.1,2,11

Preexisting Skin Conditions

Preexisting skin conditions (e.g., atopic dermatitis; psoriasis; candidal and other fungal infections; cutaneous tumors including molluscum fibrosum gravidarum and malignant melanoma) may change during pregnancy. Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis may worsen or improve during pregnancy. Atopic changes may be related to prurigo of pregnancy and usually worsen, but may improve, during pregnancy.13 Psoriasis is more likely to improve than worsen. Fungal infections generally require a longer treatment course during pregnancy.14 Soft-tissue fibromas (skin tags) can occur on the face, neck, upper chest, and beneath the breasts during late pregnancy. These fibromas generally disappear post-partum.1 The effects of pregnancy on the development and prognosis of malignant melanoma has been extensively debated15; however, a recent retrospective cohort study of pregnant women with melanoma showed no evidence that pregnancy affects survival.16

Pregnancy-Specific Dermatologic Disorders

| Condition | Rash presentation | Pregnancy risk | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy17 | Intensely pruritic urticarial plaques and papules with or without erythematous patches of papules and vesicles; rash first appears on abdomen, often along striae and occasionally involves extremities; face usually is not affected | No identified adverse effects | Oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids for pruritus; systemic corticosteroids for extreme symptoms |

| Prurigo of pregnancy1 | Erythematous papules and nodules on the extensor surfaces of the extremities | No identified adverse effects | Midpotency topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy1,18,19 | Excoriations from scratching; distribution is nonspecific | Risk of premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, intrauterine fetal demise | Oral antihistamines for mild pruritus; ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) for more severe cases |

| Pemphigoid gestationis20,21 | Pruritic papules, plaques, and vesicles evolving into generalized vesicles or bullae; initial periumbilical lesions may generalize, although the face, scalp, and mucous membranes usually are not affected | Newborns may have urticarial, vesicular, or bullous lesions; risk of premature deliveries andnewborns who are small for gestational age | Oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids for mild cases; systemic oral corticosteroids for severe cases |

| Impetigo herpetiformis22,23 | Round, arched, or polycyclic patches covered with small painful pustules in a herpetiform pattern; most commonly appears on thighs and groin, but rash may coalesce and spread to trunk and extremities; face, hands, and feet are not affected; mucous membranes may be involved | Reports of increased fetal morbidity | Systemic corticosteroids; antibiotics for secondarily infected lesions |

| Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy1 | Erythematous follicular papules and sterile pustules on the abdomen, arms, chest, and back | No identified adverse effects | Topical corticosteroids, topical benzoyl peroxide (Benzac), or ultraviolet B light therapy |

PUPPP

PUPPP (Figure 3), is the most common pregnancy-specific dermatosis, occurring in one out of 130 to 300 pregnancies.1 A PUPPP- associated rash, characterized by intense pruritus, develops in the third trimester and generally first appears on the abdomen, often along the striae.17 The disorder is more common with first pregnancies and multiple gestations, and familial occurrences have been reported.18

Despite its frequency, the etiology of PUPPP remains unclear. A relationship between the condition and the maternal immune system and fetal cells has been proposed.24 An increased incidence in women with multiple gestations suggests that skin stretching may play a role in inciting an immune-mediated reaction. Histopathologic findings are nonspecific.18

There is no specific treatment for PUPPP, and it is not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Antihistamines and topical steroids may be used to treat pruritus, and systemic corticosteroids may be used for extreme pruritus.18 The rash typically resolves one to two weeks after delivery.

PRURIGO OF PREGNANCY

The cause of this condition is unclear, and there are no recognized adverse effects for the mother or fetus. An association with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy or a history of atopy has been suggested.18 Mid-potency topical steroids and oral antihistamines may provide symptomatic relief.

INTRAHEPATIC CHOLESTASIS OF PREGNANCY

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy historically has been referred to as pruritus gravidarum because its classic presentation is severe pruritus in the third trimester. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy occurs in one out of 146 to 1,293 pregnancies in the United States.1

Diagnosis is based on clinical history and presentation: pruritus with or without jaundice, no primary skin lesions, and laboratory markers of cholestasis. The condition usually resolves postpartum.1,18,19 Laboratory markers include elevated serum bile acid levels (4.08 mcg per mL [10 μmol per L] or more) and alkaline phosphatase levels with or without elevated bilirubin levels.25 However, alkaline phosphatase levels normally are elevated in pregnant women, limiting the usefulness of this test.19 Aspartate and alanine transaminase levels and other liver function tests may be mildly abnormal. Cholestasis and jaundice in patients with severe or prolonged intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy may cause vitamin K deficiency and coagulopathy.18

The etiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy remains controversial. A family history of the condition is common, and there is an association with the presence of human leukocyte antigen-A31 (HLA-A31) and HLA-B8.1,18 The condition tends to recur in subsequent pregnancies.1 Patients may have a family history of cholelithiasis and a higher risk of gallstones.25,26 The condition is associated with a higher risk of premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine demise. A prospective cohort study demonstrated a correlation between bile acid levels and fetal complications, with a statistically significant increase in adverse fetal outcomes reported in patients with bile acid levels of 16.34 mcg per mL (40 μmol per L) or more.25

Patients with mild pruritus may be treated with oral antihistamines. Patients with more severe cases require ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol [Actigall]) to relieve pruritus and improve cholestasis while reducing adverse fetal outcomes.18,27 Current evidence does not support treatment with S-adenosylmethionine, anion exchange resins (e.g., cholestyramine [Questran]), or corticosteroids.18,28 Patients should receive increased antenatal surveillance at the time of diagnosis, and some authorities recommend delivery by 38 weeks' gestation. The impact of early delivery on perinatal complications is not completely clear.29

PEMPHIGOID GESTATIONIS

Pemphigoid gestationis (Figure 5), sometimes referred to as herpes gestationis, is an autoimmune skin disorder that occurs in one out of 50,000 mid- to late-term pregnancies.20 Pemphigoid gestationis has been linked to the presence of HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4 and is rarely associated with molar pregnancies and choriocarcinoma.18,21 Patients with a history of the condition have an increased risk of other autoimmune diseases (e.g., Graves' disease).30

The disease may take a variable course, although it generally improves in late pregnancy, with exacerbations in the immediate postpartum period. Flare-ups have been associated with oral contraceptive use and are common during subsequent pregnancies.18 Immunodiagnostic studies reveal characteristic deposits of complement 3 along the dermoepidermal junction.30 Fetal risk has not been substantiated, although immunoglobulin G autoantibodies cross the placenta, and 5 to 10 percent of newborns have urticarial, vesicular, or bullous lesions.30 Mild placental failure has been associated with premature deliveries and newborns who are small for gestational age. Therefore, antenatal surveillance should be considered.22 Patients with mild pemphigoid gestationis may respond to oral antihistamines and systemic topical corticosteroids, whereas patients with more severe symptoms may need oral corticosteroids.

IMPETIGO HERPETIFORMIS

Systemic signs and symptoms of impetigo herpetiformis include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, chills, and lymphadenopathy. Pruritus generally is absent. Medical complications (e.g., secondary infection, septicemia, hyperparathyroidism with hypocalcemia, hypoalbuminemia) may occur.1

Treatment of impetigo herpetiformis includes systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics to treat secondarily infected lesions. Prednisone, 15 to 30 mg to as high as 50 to 60 mg per day followed by a slow taper, may be necessary.1,22,23 The disease typically resolves after delivery, although it may recur during subsequent pregnancies. The extent of fetal risk is somewhat controversial; however, increased fetal morbidity has been reported, suggesting the need for increased antenatal surveillance.22

PRURITIC FOLLICULITIS OF PREGNANCY

Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy occurs in the second and third trimesters and presents as erythematous follicular papules and sterile pustules. Contrary to its name, pruritus is not a major feature. Spontaneous resolution occurs after delivery. This condition likely is underreported because it often is misdiagnosed as bacterial folliculitis.18

The etiology of pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy is uncertain, and there are no reports of adverse fetal outcomes clearly related to the condition. Treatments include topical corticosteroids, topical benzoyl peroxide (Benzac), and ultraviolet B light therapy.1