This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(12):1815-1824

A more recent article on the differential diagnosis of the swollen red eyelid is available.

Patient information: See related handout on herpes zoster ophthalmicus.

Author disclosure: Dr. Papier is chief scientific officer for Logical Images, Inc.

The differential diagnosis of eyelid erythema and edema is broad, ranging from benign, self-limiting dermatoses to malignant tumors and vision-threatening infections. A definitive diagnosis usually can be made on physical examination of the eyelid and a careful evaluation of symptoms and exposures. The finding of a swollen red eyelid often signals cellulitis. Orbital cellulitis is a severe infection presenting with proptosis and ophthalmoplegia; it requires hospitalization and intravenous antibiotics to prevent vision loss. Less serious conditions, such as contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and blepharitis, are more common causes of eyelid erythema and edema. These less serious conditions can often be managed with topical corticosteroids and proper eyelid hygiene. They are differentiated on the basis of such clinical clues as time course, presence or absence of irritative symptoms, scaling, and other skin findings. Discrete lid lesions are also important diagnostic indicators. The finding of vesicles, erosions, or crusting may signal a herpes infection. Benign, self-limited eyelid nodules such as hordeola and chalazia often respond to warm compresses, whereas malignancies require surgical excision.

Patients with eyelid erythema and edema often present first to the family physician. Cellulitis may be suspected in patients with a red, swollen eyelid, although dermatitis is a more common cause. The differential diagnosis of eyelid edema is extensive, but knowledge of the key features of several potential causes can assist physicians in diagnosing this condition (Table 1). Particular attention must be paid to visual clues, exposures, and other historical factors in the work-up of patients with eyelid edema (Figure 11,2 ).

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Allergic contact dermatitis of the eyelids should be treated with low-dose topical steroids for five to 10 days. | C | 1 |

| Eyelid atopic dermatitis should be treated with oral antihistamines; moisturizers; and low-dose, short-term topical corticosteroids. Only low-dose topical corticosteroids should be used on the eyelids to avoid skin atrophy. | C | 1, 31 |

| First-line treatment of blepharitis consists of eyelid hygiene and systemic tetracyclines in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. | B | 35 |

| Mild preseptal cellulitis in older children and adults often can be treated on an outpatient basis with broad-spectrum oral antibiotics and close follow-up. Treatment of orbital cellulitis requires ophthalmology consultation, hospital observation, and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. | C | 38, 39, 41 |

| Treatment of ocular rosacea includes oral tetracyclines and topical metronidazole (Metrogel) or azelaic acid gel (Finacea). | B | 45–47 |

| Condition | Signs and symptoms | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions typically presenting bilaterally | |||

| Angioedema |

|

| |

| Atopic dermatitis |

|

| |

| Blepharitis |

|

| |

| Contact dermatitis |

|

| |

| Rosacea |

|

| |

| Systemic processes |

|

| |

| Conditions typically presenting unilaterally | |||

| Cellulitis* |

|

| |

| Herpes simplex |

|

| |

| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus |

|

| |

| Tumors |

|

| |

Contact Dermatitis

Contact dermatitis is the most common cause of cutaneous eyelid inflammation.3–6 Eyelid skin is especially vulnerable to irritants and allergens because of its thinness and frequent exposure to chemicals via direct application or contamination from fingers and hands.3,7 As one of the most sensitive areas, eyelid skin may be the initial or only presenting area with signs of contact dermatitis, while other areas of the body remain unaffected by the same exposure.7

Contact dermatitis can be classified as allergic or irritant. The presenting features of these types often are not readily distinguishable, but patients with irritant contact dermatitis often present with greater burning and stinging compared with the characteristic pruritus of allergic contact dermatitis.1,7,8

ETIOLOGY

Contact dermatitis of the eyelid is mediated by a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in allergic contact dermatitis and by direct toxic effect in irritant contact dermatitis.1 It is more often caused by a product applied to the hair, nails, or face than by products applied directly to the eyelids.7 Table 2 lists common exposures that can cause contact dermatitis.8–23

DIAGNOSIS

A careful history of exposure to agents known to cause eyelid contact dermatitis should be elicited. The patient should be asked about his or her occupation, hobbies, and cosmetic use (including non-eye cosmetics, new products, and refills of a previously used product, because changes in cosmetic formulations are common).7 Patients with irritant contact dermatitis may have pruritus, burning, or stinging of the eyelids and periorbital area, with or without involvement of the face and hands.1 Examination may reveal a combination of erythema, edema, and vesiculation in patients with acute dermatitis, or scaling and desquamation if inflammation has been present for weeks2 (Figure 2). If the causative agent is not apparent after taking the history and performing the physical examination, referral to an allergist or dermatologist for patch testing may uncover an occult allergen.

TREATMENT

Treatment of contact dermatitis involves avoidance of the offending agent.1,7 The patient should receive a list of common allergens or irritants and be instructed to carefully read all product labels. Acute allergic contact dermatitis of the eyelids can be treated with low-dose topical steroids twice daily for five to 10 days.1 Long-term use of these medications on the eyelid can cause skin atrophy and glaucoma24 or cataracts25; therefore, it is important to use the lowest potency preparation for the shortest period of time necessary to clear the eruption. Although delayed-type reactions of allergic contact dermatitis do not involve histamine release from mast cells, oral antihistamines may provide symptomatic relief as a result of their antipruritic and soporific effects.26

Patients with irritant contact dermatitis may find it useful to apply a cool compress followed by an emollient.1 The use of topical steroids for irritant contact dermatitis was found to be ineffective in at least one study.27 However, in practice, steroids are often used because it can be difficult to differentiate between irritant and allergic contact dermatitis.

Atopic Dermatitis

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of atopic dermatitis is thought to involve a combination of complex genetic, environmental, and immunologic interactions. There is often a strong familial pattern of inheritance. Altered T-cell function is present in the form of heightened T-helper 2 subtype activity. Inciting or exacerbating factors include aeroallergens, chemicals, foods, and emotional stress. Skin barrier function is also decreased in patients with atopic dermatitis, making them more sensitive to such allergens and irritants.28

DIAGNOSIS

Patients with atopic dermatitis involving the eyelid may present with pruritus, edema, erythema, lichenification, fissures, or fine scaling.1 Typically, edema and erythema of the eyelid are less prominent in atopic dermatitis than in contact dermatitis, and lichenification and fine scaling predominate (Figure 3). In some cases, however, the lesions may be difficult to distinguish from contact dermatitis.29 In these cases, the diagnosis may be made by the recognition of other features consistent with atopic dermatitis, such as a flexural distribution in older children and adults and a family history of asthma, rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis.30

Atopic dermatitis may become complicated by infection or contact dermatitis, making the diagnosis more difficult. These complications should be suspected in patients who develop new or acute inflammation of the eyelid in the setting of well-controlled atopic dermatitis.1

TREATMENT

Treatment involves oral antihistamines; moisturizers; and low-dose, short-term topical corticosteroids.1,31 The topical immunomodulators tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) may be used in refractory cases. These agents are safe for use on the eyelids and face,32,33 but they should be reserved as second-line therapies because of their association with several types of cancer in animal studies and human case reports.34

Blepharitis

Blepharitis is a common chronic inflammatory condition of the eyelid margins. It may be classified according to anatomic location: anterior blepharitis affects the base of the eyelashes, whereas posterior blepharitis involves the meibomian gland orifices. Blepharitis is often associated with other disorders such as rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca.35

ETIOLOGY

The exact etiology of blepharitis is unknown. Anterior blepharitis is often attributed to staphylococcal infection or seborrhea, whereas posterior blepharitis generally results from meibomian gland dysfunction.35

DIAGNOSIS

Patients with blepharitis will have erythematous and mildly edematous eyelid margins. Soft, oily, yellow scaling or, rarely, brittle scaling around the lashes distinguishes blepharitis from other causes of eyelid inflammation. Patients may have itching, irritation, and burning.2,36 Culture of the eyelid margins may be indicated for patients with recurrent anterior blepharitis and for those unresponsive to therapy. Biopsy to rule out carcinoma may be needed in particularly recalcitrant cases.35

TREATMENT

Eyelid hygiene is the mainstay of treatment. Warm compresses are recommended, followed by gentle massage to express meibomian secretions. Eyelid scrubbing with dilute baby shampoo or eyelid cleanser may provide further relief. For patients with staphylococcal blepharitis, a topical antibiotic applied at bedtime for a week or more may speed resolution. Oral tetracyclines may be prescribed for patients with meibomian gland dysfunction.35 Short courses of low-dose topical corticosteroids may also be trialed.35 Because blepharitis may lead to such sequelae as madarosis (i.e., loss of eyelashes), trichiasis (i.e., misdirected eyelashes), and corneal scarring, patients with refractory cases should be referred to an ophthalmologist.35

Preseptal and Orbital Cellulitis

Preseptal and orbital cellulitis are infections of the eyelid or orbital tissue that present with eyelid erythema and edema. Although these conditions are less common causes of eyelid edema than contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis, immediate recognition and treatment are critical to prevent vision loss and other serious complications, such as meningitis and cavernous sinus thrombosis.

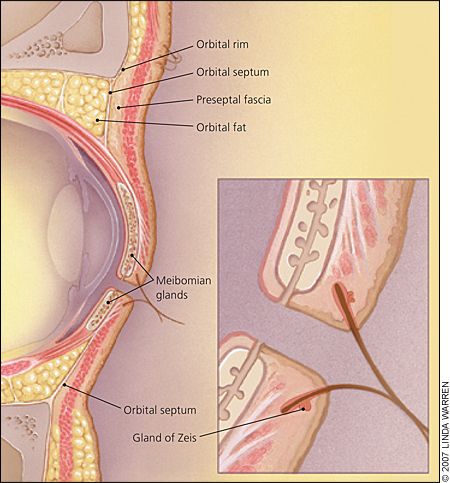

An understanding of the anatomy of the eyelid is important in distinguishing preseptal from orbital cellulitis. The orbital septum is a sheet of connective tissue that extends from the orbital bones to the margins of the upper and lower eyelids37; it acts as a barrier to infection deep in the orbital structures38 (Figure 4). Infection of the tissues superficial to the orbital septum is called preseptal cellulitis, whereas infection deep in the orbital septum is termed orbital cellulitis.38 Distinguishing between the conditions is important in determining appropriate treatment. Both preseptal and orbital cellulitis are more common in children than adults.39

ETIOLOGY

Preseptal cellulitis is caused by contiguous spread from upper respiratory tract infection, local skin trauma, abscess, insect bite, or impetigo.25 Sinusitis is implicated in 60 to 80 percent of cases of orbital cellulitis.26 Surgery, trauma, or complication from preseptal cellulitis or dacryocystitis can also cause orbital cellulitis.26 The pathogens responsible for most cases of preseptal and orbital cellulitis include Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus species, and Streptococcus species.39 Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates have increasingly been found in patients with preseptal and orbital cellulitis.40

DIAGNOSIS

Preseptal and orbital cellulitis must be differentiated from other diseases that may present similarly, including trauma, malignancy, contact dermatitis, and allergic reactions.39 A history of sinusitis, fever, malaise, local trauma, impetigo, or surgery may help differentiate cellulitis from other processes.39

Physical examination is key to differentiating between preseptal and orbital cellulitis. Although both conditions may present with eyelid edema and erythema, orbital cellulites (Figure 5) presents with additional signs and symptoms, including proptosis, decreased visual acuity, pain with eye movement, limitation of extraocular movements, and afferent papillary defect (i.e., an interference with the input of light to the pupillomotor system resulting in a symmetrical decrease in contraction of both pupils to light given to the damaged eye, compared with light given to the less damaged or normal eye).38,39

In patients with suspected orbital cellulitis, contrast computed tomography (CT) should be ordered to evaluate the extent of the infection and to look for periosteal abscess. Other tests include a white blood cell count, conjunctival cultures, and blood cultures.38

TREATMENT

Mild preseptal cellulitis in older children and adults can often be treated on an out-patient basis with broad-spectrum oral antibiotics (e.g., dicloxacillin (Dynapen), amoxicillin/clavulanate [Augmentin]) and close follow-up.38,39,41 Preseptal cellulitis in children younger than four years may warrant hospitalization and the use of intravenous antibiotics.38 If orbital cellulitis is suspected after examination or CT imaging, referral to an ophthalmologist or otolaryngologist is necessary.38 All patients with orbital cellulitis require hospital observation and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (e.g., ampicillin/sulbactam [Unasyn], second- or third-generation cephalosporins).38,39,41 With the increasing prevalence of community-acquired MRSA, alternative empiric therapeutic regimens may be necessary. Such therapies include clindamycin (Cleocin), trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra), doxycycline (Vibramycin), and minocycline (Minocin). Patients with community-acquired MRSA orbital cellulitis may require intravenous therapy with vancomycin (Vanocin, intravenous formulation no longer available in the United States), linezolid (Zyvox), or daptomycin (Cubicin).42

Other Potential Causes

ANGIOEDEMA

Angioedema refers to deep dermal swelling mediated by a type I allergic reaction, which is triggered by shellfish, medications, or other allergens. This condition may present with swollen eyelids similar to cellulitis; however, it most often occurs bilaterally and concurrently with swelling of other distensible regions of the body, particularly other facial structures and the extremities. Cellulitis tends to be associated with a more violaceous skin color and increased pain.36 Angioedema is often self-limited, but upper airway involvement warrants emergency medical attention.

EXTERNAL HORDEOLUM, INTERNAL HORDEOLUM, AND CHALAZION

A chalazion is a sterile nodular lipogranulomatous inflammation of a meibomian gland. It is painless and nonerythematous.2 First-line treatment in all of these conditions includes warm compresses to encourage localization and spontaneous drainage. Topical antibiotics may be applied to hordeola to limit the spread of infection. Recalcitrant lesions may require ophthalmology referral for incision and drainage.43

ROSACEA

Rosacea is a chronic skin condition most commonly affecting adults in their fourth and fifth decades of life. It usually presents with flushing, erythema, and telangiectasias of the face. Some patients develop papules and pustules of the nose, cheek, forehead, and chin. Although eyelid involvement usually accompanies general cutaneous disease manifestations that affect the entire face, the ocular signs of rosacea may develop first.31 Eyelid involvement can manifest as acneiform eruptions of the lids, periorbital edema and erythema, telangiectasia of the lid margins, and variably thickened and irregular eyelids.1,43,44 Treatment consists of eyelid hygiene, systemic tetracyclines,45 topical metronidazole (Metrogel),46 or 15% azelaic acid gel (Finacea).47 However, azelaic acid gel is more irritating than metronidazole, and patients should be cautioned to avoid getting the gel in their eyes.48 Patients with severe rosacea may develop corneal neovascularization and scarring; these patients should be referred to an ophthalmologist.35

HERPES SIMPLEX AND HERPES ZOSTER OPHTHALMICUS

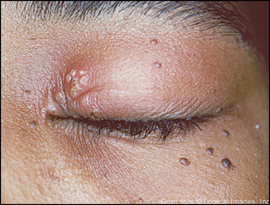

Herpes simplex with eyelid involvement is uncommon and presents with unilateral crops of small vesicles with swelling and erythema. In some cases, the vesicles can be very subtle or have previously ruptured to form erosions, complicating the diagnosis (Figure 6). The vesicles typically scab and heal without scarring.2,28

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a common condition that presents in a unilateral V1 nerve distribution. It is a painful maculopapular rash, with vesicles, crusting, ulceration, erythema, and edema. This condition occurs most often in older adults. Patients generally have headache, fever, and malaise.2 Treatment with systemic antiviral agents is indicated, and referral to an ophthalmologist should be made to evaluate for sequelae such as corneal disease and iritis.49

MALIGNANT TUMORS

Basal cell carcinoma accounts for about 90 percent of all malignant eyelid tumors, whereas squamous cell carcinoma comprises 5 percent.50 Both types of tumors are seen predominantly in older, light-skinned persons with a history of chronic sun exposure, and lesions are found most often on the lower eyelid and medial canthus.50 Clinical presentation often varies, but a common finding is that of a nodule with associated telangiectasias that may ulcerate. The treatment of choice for both types of tumor is Mohs micrographic surgery.51

Sebaceous carcinoma accounts for approximately 1 to 5 percent of malignant eyelid tumors.50 Discrete sebaceous carcinomas are painless, nontender nodules that arise in meibomian or Zeis glands or in sebaceous glands of the caruncle. They may mimic chronic chalazia. These tumors are found most often on the upper eyelid and caruncle,50 and they are more aggressive than basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma. These tumors are treated with wide excision.

SYSTEMIC DISORDERS

Systemic disorders such as myxedema, renal disease, congestive heart failure, and superior vena cava syndrome may manifest with periorbital edema. Generalized or regional edema as well as other signs and symptoms consistent with each respective disease should also be apparent. A periocular “heliotrope rash” may be the initial presenting sign of dermatomyositis, an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy.52,53 Other systemic disorders associated with discrete eyelid eruptions include amyloidosis,54 discoid lupus erythematosus,55 Sjögren's syndrome,56 and Wegener's granulomatosis.57