Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(7):845-852

Editorial: “Promoting Oral Health: The Family Physician's Role,” p. 814.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Older persons are at risk of chronic diseases of the mouth, including dental infections (e.g., caries, periodontitis), tooth loss, benign mucosal lesions, and oral cancer. Other common oral conditions in this population are xerostomia (dry mouth) and oral candidiasis, which may lead to acute pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush), erythematous lesions (denture stomatitis), or angular cheilitis. Xerostomia caused by underlying disease or medication use may be treated with over-the-counter saliva substitutes. Primary care physicians can help older patients maintain good oral health by assessing risk, recognizing normal versus abnormal changes of aging, performing a focused oral examination, and referring patients to a dentist, if needed. Patients with chronic, disabling medical conditions (e.g., arthritis, neurologic impairment) may benefit from oral health aids, such as electric toothbrushes, manual toothbrushes with wide-handle grips, and floss-holding devices.

It is estimated that 71 million Americans, approximately 20 percent of the population, will be 65 years or older by 2030.1 An increasing number of older persons have some or all of their teeth intact because of improvements in oral health care, such as community water fluoridation, advanced dental technology, and better oral hygiene.1 However, this population is at risk of chronic diseases of the mouth, including dental infections (e.g., caries, periodontitis), tooth loss, benign mucosal lesions, and oral cancer. Table 1 summarizes common oral conditions in older patients.1–20 Increasing evidence has linked oral health and general health, suggesting a relationship between periodontal disease and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, pneumonia, rheumatologic diseases, and wound healing.8,21–24

| Clinical recommendations | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Fluoride gels, rinses, and varnishes may prevent or reduce root caries. | C | 7 |

| Patients with xerostomia should be encouraged to drink water, avoid alcohol and foods and drinks that contain sugar, and use over-the-counter saliva substitutes as needed. | C | 19 |

| Topical antifungal therapies are effective for treating denture stomatitis and angular cheilitis caused by candidiasis. | A | 17 |

| Condition | Clinical presentation | Treatment | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental caries1–6 | Coronal (above the gum) or root: painful brownish discoloration with cavitation | Root caries may be treated with fluoride gels, varnishes, or toothpaste; effective for some shallow caries | Infection can be reduced with good oral hygiene and professional dental care; patients should avoid sugary foods and drinks; see Table 2 for risk factors | |

| Gingivitis7 | Red, swollen, bleeding gums | Good oral hygiene, including brushing and flossing daily | — | |

| Periodontitis6,8–12 | Gingivitis, gingiva recession, loose or shifting teeth | Good oral hygiene, including brushing and flossing daily; dental scaling performed by a dental health professional; adjunct antibiotic therapy | Associated with cardiovascular disease, worsening diabetes, and aspiration pneumonia | |

| Xerostomia7,13 | Swollen, dry, red tongue; burning sensation; difficulty with speech and swallowing; change in taste | Saliva substitutes; sugar-free gum or pilocarpine (Salagen) and cevimeline (Evoxac) drops may stimulate saliva production | See Table 3 for risk factors | |

| Candidiasis14–17 | Acute pseudomembranous (thrush): adherent white plaques that can be wiped off Erythematous (denturestomatitis): red macular lesions, often with a burning sensation Angular cheilitis: erythematous, scaling fissures at the corners of the mouth | Topical antifungals (e.g., nystatin oral suspension or troche [Mycostatin; brand no longer available in the United States]; clotrimazole troche [Mycelex]) Or Systemic antifungals (e.g., fluconazole[Diflucan]; ketoconazole [Nizoral; brand no longer available in the United States]; itraconazole [Sporanox]) | Diagnosis can be confirmed with oral exfoliative cytology (stained with periodic acid-Schiff or potassium hydroxide), biopsy, or culture | |

| Denture stomatitis18,19 | Varying erythema, occasionally accompanied by petechial hemorrhage; localized to the denture-bearing areas of the removable maxillary prosthesis; usually asymptomatic | Removal of dentures at night; topical antifungals (see Candidiasis) placed inside the denture-fitting surface | Dentures should be removed and cleaned at least once daily | |

| Oral cancer20 | Nonhealing ulcer or mass | Refer for biopsy, staging, surgery, and other treatment | — | |

Poor oral health is often associated with lower economic status; lack of dental insurance; being homebound or institutionalized; and the presence of physical disabilities that limit good oral hygiene, such as arthritis and neurologic impairment.25 Because older patients are more likely to visit a physician than a dentist, primary care physicians have an opportunity to improve oral health in this population by assessing oral health risk, identifying and treating common oral conditions, and referring patients to a dentist, if needed.

Oral Health Assessment

An abbreviated history checklist that patients may fill out in the physician's office or at home can help physicians assess oral health risk. There are also screening tools that can be administered by non-dental professionals in a residential care facility. Figure 1 is a simple, valid, and reliable dental screening tool.26 The only materials needed to perform the assessment are a penlight, gloves, and a tongue blade. Eight oral health categories are marked as healthy, changed, or unhealthy to help determine the next steps in the patient's care.

Smiles for Life: A National Oral Health Curriculum for Family Medicine is an educational resource developed by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Group on Oral Health.27 The Web site (http://www.smilesforlife2.org) includes free pocket cards and personal digital assistant downloads.

Age-Related Oral Changes

With aging, the appearance and structure of teeth tend to change.28 Yellowing (Figure 2) or darkening of the teeth is caused by changes in the thickness and composition of the underlying dentin and its covering, the enamel. Abrasion and attrition also contribute to changes in tooth appearance.29 The number of blood vessels entering a tooth and the enamel decrease with age, leading to reduced sensitivity.30 With less sensitivity to environmental stimuli, the response to caries (decay) or trauma may decrease. The cementum (i.e., the substance covering the root surface) gradually thickens, with the total width almost tripling between 10 and 75 years of age. Because the cementum is highly organic, it is less resistant to environmental agents, such as sugar, acids from soft drinks, and tobacco, which has a drying effect.

Age-related changes in the oral mucosa and dietary or hormonal deficiencies lead to diminished keratinization, dryness, and thinning of the epithelial structures. Additionally, the width and fiber content of the periodontal ligament, which is a part of the attachment apparatus of the periodontium, decreases with aging. Gingival recession is another common condition in older persons, but is not considered a normal age-dependent oral change. Gingival recession exposes the cementum, possibly leading to root caries.31

Dental Caries

Dental caries can occur at any age. However, because of gingival recession and periodontitis, older persons are at higher risk of developing root caries (Figure 3). The incidence of root caries in patients older than 60 years is twice that of 30-year-olds7; 64 percent of persons older than 80 years have root caries, and up to 96 percent have coronal caries (above the gum).32 Risk factors (Table 213) for coronal and root caries lead to increased exposure to cariogenic bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacillus, and Actinomyces.7

| Decreased salivary flow rate |

| History of caries |

| Institutionalization |

| Lack of routine dental care |

| Low socioeconomic status |

| Nonfluoridated community water supply |

| Poor oral hygiene |

Periodontal Disease

GINGIVITIS

Plaque is a biofilm composed of gram-negative bacteria and endotoxins that develops on teeth at the gingival margins, leading to gingival inflammation (gingivitis). Gingivitis (Figure 4) is characterized by erythematous and edematous gingival tissue, which often bleeds easily with instrument probing and gentle brushing. Other causes of gingivitis include trauma and tobacco use. Although gingivitis is more common in older persons, age alone is not a risk factor for gingivitis or periodontitis.7 Gingivitis can be reversed with good oral hygiene.

PERIODONTITIS

Periodontitis (Figure 5) occurs when gingival inflammation causes the periodontal ligament to detach from the cementum and tooth structure, leading to increased gingival pocket depth, loosening of the tooth, and, ultimately, tooth loss.33 Many older persons are prone to periodontal detachment and tooth loss because of poor oral hygiene and gingival recession.34 Periodontitis has been associated with cardiovascular disease, worsening diabetes control, poor wound healing, and aspiration pneumonia, particularly in institutionalized patients.4,8,21–23,35

Treatment of periodontal disease includes daily brushing and flossing and professional dental care, ranging from plaque removal to surgical debridement of infected periodontium. Oral antibiotics, such as doxycycline (Periostat), have been used as adjuncts to scaling and root planing in older patients who are institutionalized.9 Along with regular dental cleanings, these interventions can reduce the need for surgical debridement and tooth removal.9–11,33

Xerostomia

Xerostomia, the subjective sensation of dry mouth caused by decreased saliva production, affects 29 to 57 percent of older persons.13,36 Saliva lubricates the oral cavity, prevents decay by promoting remineralization of teeth, and protects against fungal and bacterial infections.34 In addition to dry mouth, clinical manifestations of xerostomia include a burning sensation, changes in taste, and difficulty with swallowing and speech.13 Although salivary flow does not decrease with age alone, certain medications and illnesses increase the risk of xerostomia in older persons Table 3.13,37

| Head or neck radiation | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | |

| Medication use | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | |

| Alpha and beta blockers | |

| Analgesics | |

| Anticholinergics | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Antihistamines | |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Anxiolytics | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Diuretics | |

| Muscle relaxants | |

| Sedatives | |

| Salivary gland aplasia | |

| Sjögren syndrome | |

| Smoking | |

If a patient is taking a medication known to decrease salivary flow, the medication should be changed or eliminated, if possible. Patients should be encouraged to drink water, avoid alcohol, and decrease their intake of food and drinks that may promote xerostomia or caries (e.g., those that are caffeinated or contain sugar).38 Any chewing gum or candy used to induce salivation should be sugarless. Over-the-counter salivary substitutes may offer temporary relief.7,38 Medications, such as pilocarpine (Salagen) and cevimeline (Evoxac), may be beneficial, particularly in patients with Sjögren syndrome.13 Small studies have shown that acupuncture and electric toothbrushes increase salivary flow.13,25,38,39

Candidiasis

Although it is estimated that Candida species are present in the normal oral flora of healthy adults,40 certain conditions increase the risk of overgrowth in older persons. These conditions include the pathogenicity of individual Candida strains; local factors (e.g., xerostomia, denture irritation, tobacco use, steroid inhaler use); and systemic factors (e.g., immunodeficiencies, systemic corticosteroid use, antibiotic use, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, endocrine disorders, malabsorption, malnutrition).15,41–43

CLINICAL PATTERNS

The clinical pattern of oral candidiasis varies; therefore, it may be difficult to recognize. The presentation ranges from no symptoms to a prominent burning sensation or an unpleasant salty or bitter taste. The most readily recognized clinical pattern, acute pseudomembranous candidiasis (thrush), is characterized by adherent, curd-like plaques that can be removed by wiping firmly with a tongue blade or gauze (Figure 6). In patients who wear dentures, oral candidiasis may also lead to an erythematous lesion called denture stomatitis (Figure 7). Angular cheilitis (Figure 8) is a manifestation of Candida albicans or Staphylococcus aureus infection. The condition is characterized by erythematous, scaling fissures at the corners of the mouth, is often associated with intraoral candidal infection, and typically occurs in patients with accentuated skinfolds and salivary pooling in the corners of the mouth.15

DIAGNOSIS

A presumptive candidiasis diagnosis usually can be made based on the patient's history, clinical presentation, and response to anti-fungal treatment. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a cytology smear of the lesion stained with periodic-acid Schiff or a wet mount stained with 20 percent potassium hydroxide, biopsy, or culture.

TREATMENT

Oral candidiasis may be treated with topical or systemic antifungal therapy. Topical agents that are generally effective for treating uncomplicated infections include nystatin oral suspension or troche (Mycostatin, brand no longer available in the United States) or clotrimazole troche (Mycelex).14 Topical nystatin/triamcinolone ointment or cream (Mytrex, brand no longer available in the United States) is usually effective for treating angular cheilitis.15,17 In patients with denture stomatitis, a topical antifungal should be applied to the mucosa and denture base.17 If the dentures are ill fitting, a dentist may need to reline or surgically remove the excess tissue before constructing new dentures. Patients should be advised to remove and clean dentures every night at bedtime by brushing or soaking them in sodium hypochlorite solution (6 percent bleach diluted by mixing 10 parts water to one part bleach).18,19

Systemic agents, such as fluconazole (Diflucan), ketoconazole (Nizoral; brand no longer available in the United States), and itraconazole (Sporanox), are appropriate for treating infections that are resistant to topical therapy. Systemic agents are first-line therapies for patients who are unable to tolerate topical therapy, for those at high risk of systemic infection, and for those receiving chemotherapy for cancer treatment.44,45

Oral Cancer

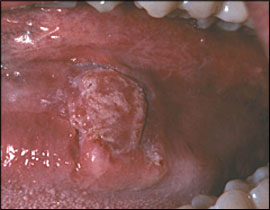

Tobacco and alcohol use are thought to be responsible for up to 75 percent of oral cancers.46 Precancerous lesions and early oral cancer can be subtle and asymptomatic. Most oral and oropharyngeal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas that arise from the lining of the oral mucosa. Oral cancer most commonly occurs, in order of frequency, on the lateral borders of the tongue, on the lips, and on the floor of the mouth (Figure 9). Fifteen percent of patients with oral cancer will be diagnosed with another cancer in a nearby area, such as the larynx, esophagus, or lungs.46 A lesion may begin as a white- or red-colored patch, progress to ulceration, and eventually become an endophytic or exophytic mass. Patients with any white or red lesion that persists for longer than two weeks should be referred to a sub-specialist for evaluation. Treatment is guided by clinical staging.20

Oral Health Aids

Good manual dexterity and a person's motivation are directly related to effective plaque removal. Diminished cognition, decreased visual acuity, or loss of strength or function in the hands may significantly alter a person's ability to maintain good oral hygiene. Specialized oral health aids, such as electric toothbrushes, manual toothbrushes with wide-handle grips, and floss-holding devices, may be necessary to remove plaque in patients with chronic disabling conditions, such as arthritis or neurologic impairment.