Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(7):465-470

A more recent article on dyspareunia in women is available.

Related letter: Lidocaine Is an Option for Treating Postmenopausal Dyspareunia

Patient information: See related handout on dyspareunia, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Dyspareunia is recurrent or persistent pain with sexual activity that causes marked distress or interpersonal conflict. It affects approximately 10% to 20% of U.S. women. Dyspareunia can have a significant impact on a woman's mental and physical health, body image, relationships with partners, and efforts to conceive. The patient history should be taken in a nonjudgmental way and progress from a general medical history to a focused sexual history. An educational pelvic examination allows the patient to participate by holding a mirror while the physician explains normal and abnormal findings. This examination can increase the patient's perception of control, improve self-image, and clarify findings and how they relate to discomfort. The history and physical examination are usually sufficient to make a specific diagnosis. Common diagnoses include provoked vulvodynia, inadequate lubrication, postpartum dyspareunia, and vaginal atrophy. Vaginismus may be identified as a contributing factor. Treatment is directed at the underlying cause of dyspareunia. Depending on the diagnosis, pelvic floor physical therapy, lubricants, or surgical intervention may be included in the treatment plan.

Dyspareunia in women is defined as recurrent or persistent pain with sexual activity that causes marked distress or interpersonal conflict.1 It may be classified as entry or deep. Entry dyspareunia is pain with initial or attempted penetration of the vaginal introitus, whereas deep dyspareunia is pain that occurs with deep vaginal penetration. Dyspareunia is also classified as primary (i.e., occurring with sexual debut and thereafter) or secondary (i.e., beginning after previous sexual activity that was not painful).2 Determining whether dyspareunia is entry or deep can point to specific causes, although the primary vs. secondary classification is less likely to narrow the differential diagnosis. The prevalence of dyspareunia is approximately 10% to 20% in U.S. women, with the leading causes varying by age group.3,4

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| An educational pelvic examination can be an informational and therapeutic tool in patients with dyspareunia. | C | 6 |

| Amitriptyline and topical analgesics may be effective medical therapies for treating vulvodynia. | C | 17, 18 |

| Estrogen preparations in cream, ring, or tablet formulations more effectively relieve symptoms of vaginal atrophy compared with placebo or nonhormonal gels. | A | 27 |

Dyspareunia can have a negative impact on a woman's mental and physical health, body image, relationships with partners, and efforts to conceive. It can lead to, or be associated with, other female sexual dysfunction disorders, including decreased libido, decreased arousal, and anorgasmia. Significant risk factors and predictors for dyspareunia include younger age, education level below a college degree, urinary tract symptoms, poor to fair health, emotional problems or stress, and a decrease in household income greater than 20%.3

History

Because dyspareunia can be distressing and emotional, the physician should first establish that the patient is ready to discuss the problem in depth. The history should be obtained in a nonjudgmental way, beginning with a general medical and surgical history before progressing to a gynecologic and obstetric history, followed by a comprehensive sexual history.5

Details of the pain can help identify the cause. If the dyspareunia is classified as secondary, the physician should ask about specific events, such as psychosocial trauma or exposure to infection, that might have triggered the pain. A description of the patient's sensations during sexual activity also can help determine the underlying cause. If penetration is difficult to achieve, the cause may be vulvodynia or accompanying vaginismus. Lack of arousal may be an ongoing reaction to pain. Lack of lubrication can occur secondary to sexual arousal disorders or vaginal atrophy. If the pain is positional, pelvic structural problems, such as uterine retroversion, may be present.6 Additional historical features pointing to specific diagnoses are outlined in Table 1.

| Diagnosis | Entry or deep | Age group | Historical clues | Physical examination findings | Additional testing | Therapeutic considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vagina and supporting structures | ||||||

| Dermatologic diseases (e.g., lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, psoriasis) | Entry | All ages | Visible lesions; burning; itching; dryness | Focal mucosal abnormalities; exact appearance depends on the diagnosis | Biopsy is often helpful in making a specific diagnosis | Treatment determined by diagnosis |

| Inadequate lubrication | Both | Most common in reproductive years |

| Vaginal mucosa may be normal or dry; evidence of trauma may be visible | Follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and estrogen levels can be checked | Treat underlying medical disorders that may be contributing; sexual arousal disorders are typically referred to subspecialists |

| Perivaginal infections (e.g., urethritis, vaginitis) | Both | All ages | Dysuria or vaginal discharge | Vaginal or cervical discharge | Appropriate cultures, DNA probes, vaginal wet mount as indicated | Antibiotic or antifungal therapy should be guided by test results |

| Postpartum dyspareunia | Both | Reproductive years | Postpartum; breastfeeding | Evidence of birth trauma; dry mucosa | Generally none needed | Vaginal lubricants; scar tissue massage or surgery for persistent cases |

| Vaginal atrophy | Both | Postmenopausal | Vaginal dryness, itching, or burning; dysuria may be present | Loss of vaginal rugae; mucosa is thin, pale, and inelastic | Generally none needed | Vaginal lubricants; systemic or local estrogen; ospemifene (Osphena), 60 mg daily |

| Vaginismus | Entry | More common in younger women | Inability or difficulty achieving entry into the vaginal cavity; history of trauma or abuse is possible | Involuntary contraction of pelvic floor muscles on attempted insertion of one finger | Identify any contributing factors, such as sexual abuse or pelvic floor dysfunction | Treat any underlying disorder; pelvic floor physical therapy; consider referral for cognitive behavior therapy or psychotherapy |

| Vulvodynia | Entry | All ages | Burning pain caused by slight touch | Vulva appears normal or erythematous | Superficial culture for Candida infection | Amitriptyline or lidocaine ointment; focal surgical excision of painful areas may be effective in refractory cases |

| Other pelvic structures | ||||||

| Adnexal pathology | Deep | All ages | Pain may be described as pelvic or lower abdominal | Fullness of adnexa; pain localized to adnexa | Pelvic imaging or laparoscopy | Determined by diagnosis |

| Endometriosis | Deep | Reproductive years | Chronic pain in pelvis, abdomen, or back | Examination may be unremarkable; masses or nodularity of pelvic structures may be found | Transvaginal ultrasonography | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists |

| Infections (e.g., endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease) | Deep | All ages | Fever and chills may be present; dysuria or vaginal discharge | Vaginal or cervical discharge | Appropriate cultures; DNA probes as indicated | Antibiotic therapy should be guided by test results |

| Interstitial cystitis | Commonly deep | All ages | Prominent urinary symptoms including frequency, urgency, and nocturia | Tenderness of bladder on palpation | Anesthetic bladder challenge or cystoscopy | Antispasmodics, immune modulators, tricyclic antidepressants, and benzodiazepines are most often used Bladder dilation and intravesicular instillations of various agents may be performed by subspecialists |

| Pelvic adhesions | Deep | All ages | History of pelvic surgery or pelvic infection | Relative lack of mobility of pelvic structures may be noted | Pelvic imaging may be inconclusive | Surgical lysis of adhesions may be considered |

| Retroverted uterus | Deep | All ages | May have received diagnosis previously | Noted on bimanual examination | Pelvic imaging can confirm diagnosis | Uterine suspension surgery; hysterectomy if childbearing is not a concern |

| Uterine myomas | Deep | Reproductive years | Menorrhagia often noted | Irregularly shaped or enlarged uterus | Pelvic ultrasonography | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, myomectomy, hysterectomy, or uterine artery embolization |

It is also important to establish which aspects of the patient's life have been impacted. Asking whether dyspareunia has negatively affected relationships or self-esteem can help the physician determine whether additional resources and support are needed.5 Some women benefit from support groups, individual therapy, or couples therapy.

Physical Examination

The physical examination may be deferred initially, providing the opportunity to establish rapport with the patient and allowing for a more focused examination later. An educational pelvic examination often increases the patient's perception of control, improves self-image, and clarifies normal and abnormal findings and how they relate to the discomfort. During the educational pelvic examination, the patient is offered the opportunity to participate by holding a mirror while the physician explains the findings.6,7

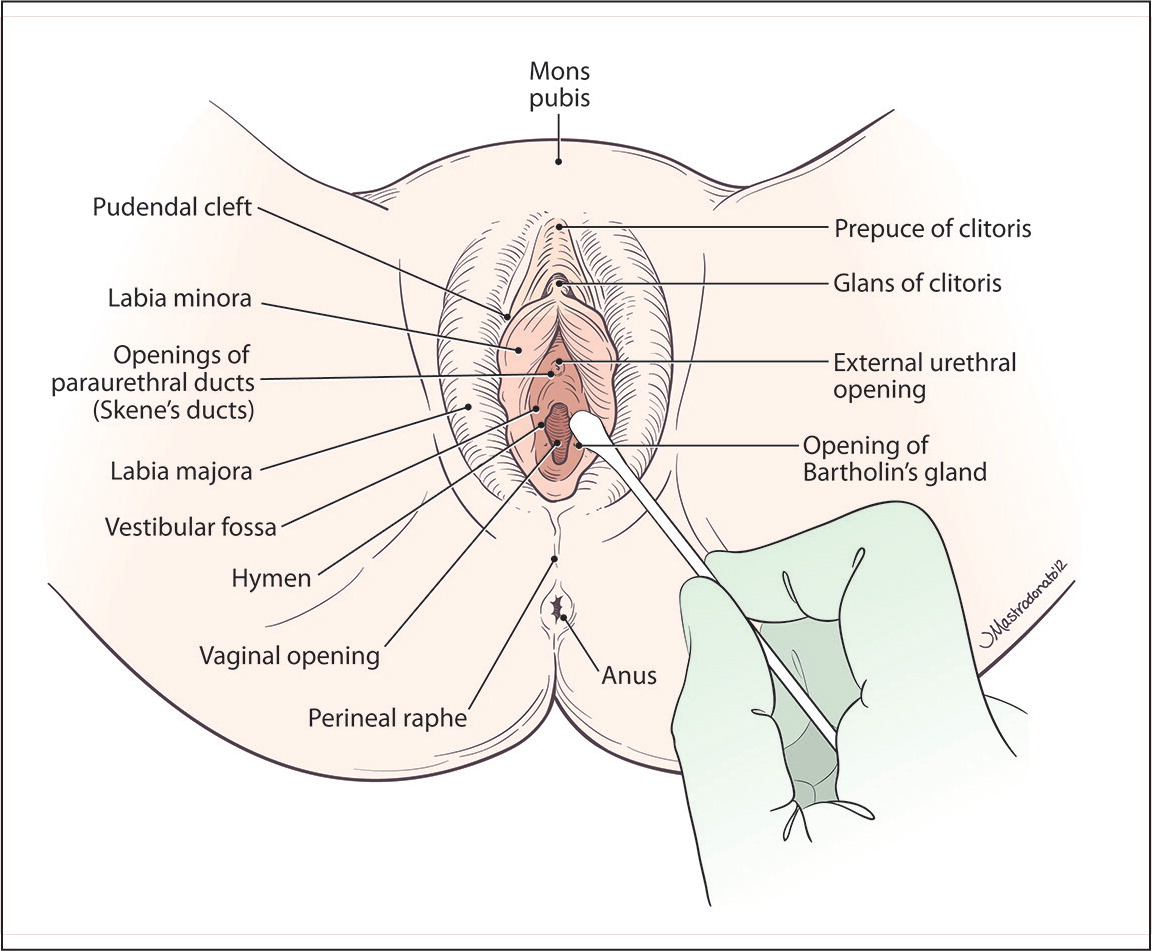

Physical examination should include visual inspection of the external and internal structures. The mucosal surfaces should be inspected for areas of erythema or discoloration, which may indicate infection or dermatologic disease, such as lichen sclerosus or lichen planus. Abrasions or other trauma indicates inadequate lubrication or forceful entry. For women who describe localized pain, a cotton swab should be used to precisely identify the source of the pain (Figure 1). Overall dryness of the vaginal mucosa suggests atrophy or chronic vaginal dryness, and abnormal discharge may suggest infection.

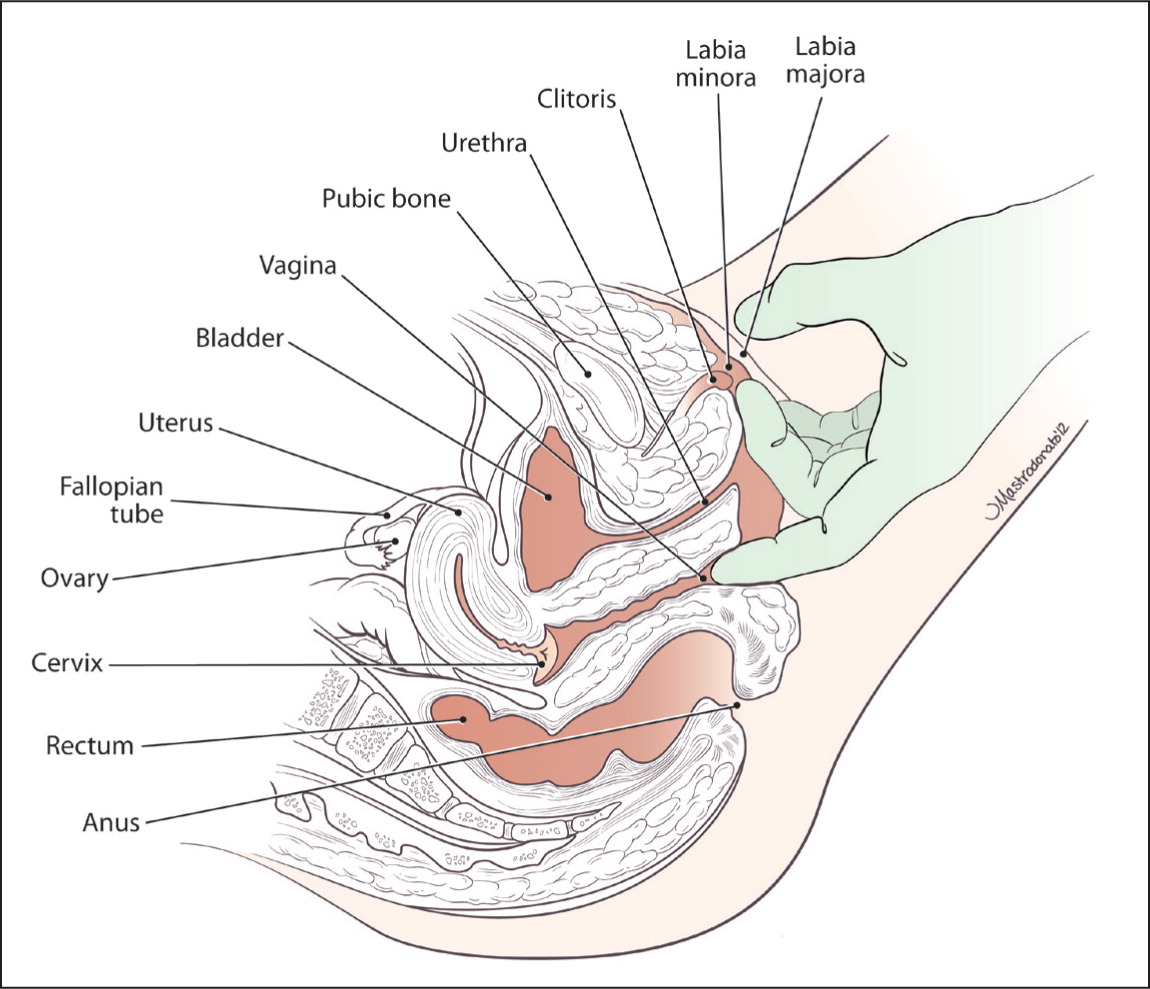

Internal examination should be performed with a single finger to maximize the patient's comfort. Muscular tightness, tenderness, or difficulty with voluntary contracting and relaxing suggests pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.8 The physician should palpate the urethra, bladder, and cervix for causes of dyspareunia associated with these organs, such as endometriosis, which may also cause rectovaginal nodularity. After the single-finger examination, a gentle bimanual examination can be used to evaluate pelvic and adnexal structures, if it is not too uncomfortable for the patient6 (Figure 2). Next, a small speculum may be used for visualization of internal structures. Testing for sexually transmitted infections is indicated if the patient has had unprotected intercourse or if discharge or other suggestive physical findings are present.

Differential Diagnosis

Although the differential diagnosis of dyspareunia is large, several features of the history and physical examination can help narrow the possibilities (e.g., type of pain, patient age). For example, vulvodynia is typically most painful with entry dyspareunia, and vaginal atrophy typically occurs in postmenopausal women. Pain that can be localized to the vagina and supporting structures may indicate vulvodynia or vaginitis. Pain that localizes to the bladder, ovaries, or colon points to pathology within those structures. Several of the most common causes of dyspareunia are described here; Table 1 provides a more comprehensive list of diagnostic possibilities.

VAGINISMUS

Vaginismus is involuntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles that inhibits entry into the vagina. The relative roles of pain, muscular dysfunction, and psychological factors in vaginismus are controversial. Whether vaginismus is a primary cause of dyspareunia or develops in response to another physical or psychosexual condition, there is significant clinical overlap between vaginismus and dyspareunia.8 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., (DSM-5) now addresses dyspareunia and vaginismus as one entity, characterized by pain, anxiety, problems with penetration, or a combination of these, rather than as separate conditions. In addition, DSM-5 amends its earlier criteria by stating that difficulties must be present for at least six months.9 Therapy typically focuses on treating underlying causes of pain in combination with pelvic floor physical therapy. Cognitive behavior therapy or psychotherapy may be included in the treatment regimen.10 OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections are a promising new therapy for vaginismus, but are not within the purview of the primary care physician.11

VULVODYNIA

Vulvodynia is defined by the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease as vulvar discomfort, most often described as burning pain, occurring in the absence of relevant visible findings or a specific, clinically identifiable, neurologic disorder.12 Vulvodynia is classified as provoked, unprovoked, or mixed. In unprovoked vulvodynia, the pain is more or less continuous. In provoked vulvodynia, the pain is triggered by touch, as with tampon insertion or intercourse. Vulvodynia can also be categorized as generalized or localized, depending on the distribution of the pain.12 There is an association between vulvodynia and psychiatric disorders. Women with depression or anxiety are at increased risk of vulvodynia, and women with vulvodynia are at increased risk of depression and anxiety.13

Physical examination reveals a normal or erythematous vulva. In provoked vulvodynia, light touch with a moist cotton swab reveals areas of intense pain, often highly localized. These areas are commonly on the posterior portion of the vestibule. Testing, such as cultures or biopsies, should focus on ruling out other potential causes of vulvar pain, such as infections or dermatologic conditions (e.g., lichen planus, psoriasis).14 A multidisciplinary team approach is needed to treat vulvodynia, and combining multiple therapies is often required.15 A variety of therapies have been used, most without solid supporting evidence.16 Amitriptyline and lidocaine ointment have been evaluated in small trials.17,18 Patients with provoked vulvodynia that is unresponsive to conservative management may be offered surgical excision of painful areas, which is effective up to 80% of the time.19

INADEQUATE LUBRICATION

Inadequate lubrication of the vagina leads to friction and microtrauma of vulvar and vaginal epithelium. It may be caused by a sexual arousal disorder or chronic vaginal dryness.10

Female sexual arousal disorder is defined as the inability to attain or maintain an adequate lubrication-swelling response from sexual excitement.1 This may be multifactorial, but important historical clues include satisfaction with current sexual relationships, negative body image, fear of pain during sex, history of sexual trauma or abuse, and restrictive personal beliefs about sexuality. Sexual arousal disorder often requires treatment by a physician with experience treating female sexual dysfunction.10

Chronic vaginal dryness may suggest an underlying medical disorder with a hormonal (e.g., hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction, premature ovarian failure, menopause), vascular (e.g., peripheral atherosclerosis, anemia), neurologic (e.g., diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury or surgery), or iatrogenic (e.g., hormonal contraceptive use, chemotherapy, radiation) cause.10 Treatment of underlying disorders and vaginal lubricants are the mainstays of therapy.20

POSTPARTUM DYSPAREUNIA

Postpartum dyspareunia is a common and under-reported disorder. After first vaginal deliveries, 41% and 22% of women at three and six months, respectively, experience dyspareunia.21 Perineal stretching, lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, and episiotomy can result in sclerotic healing and resultant entry or deep dyspareunia. The postpartum period, especially in breastfeeding women, is marked by a decrease in circulating estrogen, which can lead to vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. The psychosexual issues of the postpartum period can lead to decreased arousal and lubrication, further contributing to dyspareunia.22 Lubricants are the typical first-line treatment. Treatment of dyspareunia specifically associated with perineal trauma during childbirth is lacking robust evidence. Women who have persistent postpartum dyspareunia associated with identifiable perineal defects or scarring may benefit from revision perineoplasty, although this is usually reserved for significant anatomic distortions.23

VAGINAL ATROPHY

Dyspareunia is a common presenting symptom in women with vaginal atrophy.24,25 Vaginal atrophy affects approximately 50% of postmenopausal women because of decreasing levels of estrogen.24 It is important to inquire about vaginal symptoms in postmenopaual women. Fewer than one-half of women with vaginal atrophy have discussed it with their physician because of embarrassment, belief that nothing can be done, or that such symptoms are expected with advancing age.26 In early vaginal atrophy, the physical examination may be unremarkable. Later, the vaginal mucosa becomes thinner, paler, drier, and less elastic. Vaginal rugae are lost, the mucosa may appear irritated and friable, and the vagina shortens and narrows. Lubricants can help treat vaginal atrophy, but the most effective treatment is estrogen replacement. A 2006 Cochrane review of 19 trials involving more than 4,000 women found that estrogen preparations—cream, ring, or tablet—were associated with a statistically significant reduction in symptoms of vaginal atrophy compared with placebo or nonhormonal gels.27 In 2013, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved ospemifene (Osphena), a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator that increases vaginal epithelial cells and decreases vaginal pH, for the treatment of postmenopausal dyspareunia.28

Data Sources: A PubMed search was conducted using the key term dyspareunia combined in separate searches with the terms diagnosis, management, and treatment. Clinical reviews, randomized controlled trials, and meta-analyses were included. Also searched were the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the National Guideline Clearinghouse database, and Essential Evidence Plus. Relevant publications from the reference sections of cited articles were also reviewed. Search dates: January 9 to June 26, 2013, and June 16, 2014.

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army Medical Corps, or the U.S. Army at large.