Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(10):711-716

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Uveitis, or inflammation of the uveal tract (i.e., iris, ciliary body, and choroid), results from a heterogeneous collection of disorders of varying etiologies and pathogenic mechanisms. Uveitis is caused by a systemic disease in 30% to 45% of patients. Primary care physicians may be asked to evaluate patients with uveitis when an underlying systemic diagnosis is suspected but not apparent from eye examination or history. If the history, physical examination, and basic laboratory studies do not suggest an underlying cause, serologic tests for syphilis and chest radiography for sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are recommended. Typing for human leukocyte antigen-B27 is appropriate for patients with recurrent anterior uveitis. Because the prevalence of many rheumatologic and infectious diseases is low among persons with uveitis, Lyme serology, antinuclear antibody tests, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme tests, serum lysozyme tests, and tuberculin skin tests can result in false-positive results and are not routinely recommended. Drug-induced uveitis is rare and can occur from days to months after the time of initial exposure. Primary ocular lymphoma should be considered in persons older than 50 years with persistent intermediate or posterior uveitis that does not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy.

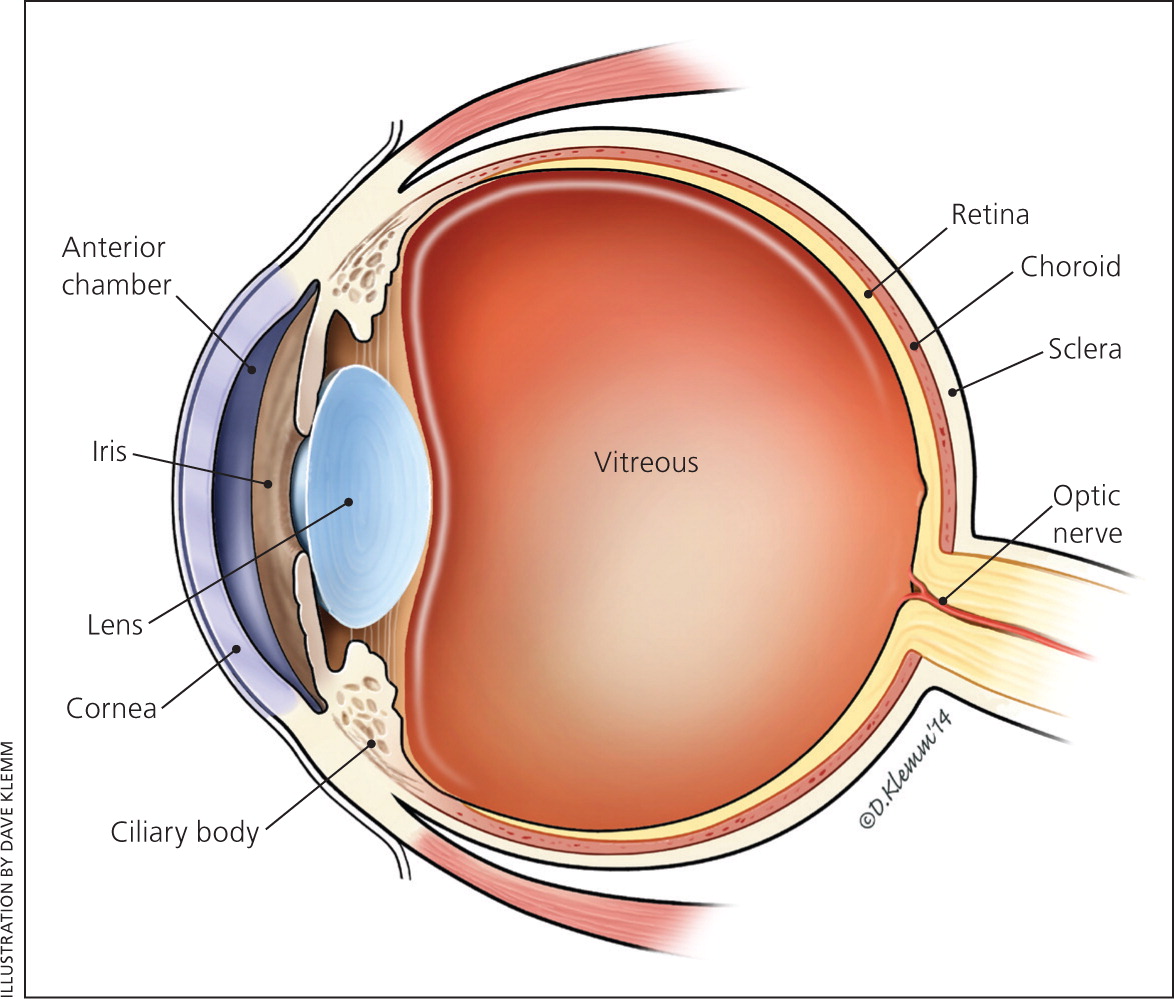

Uveitis, or inflammation of the uveal tract (i.e., iris, ciliary body, and choroid; Figure 1) is caused by a heterogeneous collection of disorders. The clinical diagnosis is often based on spillover inflammation (i.e., cells and protein flare) observed with a slit lamp in the aqueous or vitreous humors. Uveitis is classified according to the predominant site of inflammation: anterior (anterior chamber), intermediate (vitreous), or posterior (retina or choroid).1 Generalized intraocular inflammation is described as panuveitis, whereas inflammation centered in the optic nerve head with secondary peripapillary involvement is classified under posterior uveitis as neuroretinitis.1 When spillover inflammation from primary disease of the cornea or sclera occurs, the terms keratouveitis and sclerouveitis, respectively, are applicable. Classifying uveitis according to the predominant site of inflammation can help narrow the differential diagnosis.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| If the history, physical examination, and basic laboratory tests do not uncover a cause for uveitis, serologic tests for syphilis and chest radiography for sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are recommended. | C | 11, 12, 15 |

| Adults who have a single episode of mild anterior uveitis that responds to treatment and who have no systemic signs or symptoms do not need further laboratory studies. | C | 11, 13 |

| Routine radiography and serologic studies are not indicated for all patients with uveitis. | C | 13–15 |

| Drug-induced uveitis should be considered in patients with unexplained uveitis beginning days to months after starting a new medication. | C | 17–19 |

| Primary ocular lymphoma should be considered in patients older than 50 years with persistent unexplained intermediate or posterior uveitis that is unresponsive to anti-inflammatory therapy. | C | 20 |

Most forms of uveitis not caused by accidental or surgical trauma are manifestations of infectious or immune-mediated disease. Approximately 30% to 45% of patients with uveitis have a causally associated systemic disease.2,3 Topical and systemic medications can cause secondary uveitis. This review provides a framework for primary care physicians who are asked to examine patients with uveitis when an underlying systemic diagnosis is suspected after ophthalmologic evaluation.

Epidemiology

The annual incidence of uveitis in North America ranges from 17 to 52 per 100,000 persons, and the prevalence ranges from 58 to 115 per 100,000 persons.4–7 Up to 35% of patients with uveitis have severe visual impairment, and roughly 10% are legally blind.8 Uveitis can occur at any age, but the peak incidence is between 20 and 59 years of age. Systemic diseases most often associated with uveitis in North America are the seronegative spondyloarthropathies, sarcoidosis, syphilis, rheumatoid arthritis, and reactive arthritis.4–7

Table 1 lists the main systemic disorders associated with uveitis, typical clinical findings, and suggested diagnostic studies.9,10 Anatomic classification of inflammation is helpful in reducing diagnostic possibilities, but the guidance it provides is limited. Disorders like the seronegative spondyloarthropathies and juvenile idiopathic uveitis usually involve the anterior segment of the eye, but other conditions like Behçet syndrome, syphilis, and sarcoidosis can affect any location.

| Disorder | Site of predominant inflammation | Percentage of patients with uveitis | Systemic findings | Diagnostic studies | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankylosing spondylitis | Anterior | 40 | Sacroiliitis | Radiology studies | Traditional HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathy |

| Behçet syndrome | Any location | 60 to 80 | Oral and genital ulcers, erythema nodosum, arthritis, epididymitis, gastrointestinal ulcers | Positive pathergy test, HLA-B51 | Rapid onset of ocular symptoms can mimic endogenous infection |

| Bloodborne infection | Any location | Unknown | Varies with clinical context; persons with indwelling venous catheters and intravenous drug users at high risk | Blood culture | May have no systemic symptoms by the time eye symptoms develop |

| Cat-scratch disease (bartonellosis) | Neuroretinitis | Unknown | Influenza-like illness, regional lymphadenopathy | Serologic studies for Bartonella henselae | History of cat exposure |

| Drug-related uveitis | Any location | Rare | Can be associated with inflammation of conjunctiva and sclera | Withdrawal of medication; re-challenge if causation is equivocal and risk/benefit is acceptable | Most definite associations based on challenge/re-challenge test |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Usually anterior | Unknown | Sinusitis, pulmonary lesions, glomerulonephritis | c-ANCA serology | Inflammation is usually spillover from scleritis or peripheral keratitis |

| Immunocompromised state or disorder | Any location | Varies based on underlying disorder | Varies based on type of opportunistic infection | Studies to assess degree of immune dysfunction; studies to identify opportunistic organism | — |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Anterior | 15 to 55 | Diarrhea, oral ulcer, arthritis | Endoscopy | — |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Anterior | < 50 | Pauciarticular arthritis, fever | 93% are ANA positive | 5:1 girl-to-boy ratio; ocular inflammation with minimal or no symptoms |

| Lyme disease | Any location | Unknown | Erythema chronicum migrans, arthritis, other organ involvement possible | ELISA IgM and IgG, followed by Western blot test | Tick exposure history, seasonal variation |

| Multiple sclerosis | Intermediate | 30 | Multifocal disease of white matter of brain; chronic remitting and relapsing course | MRI, CSF examination | — |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Anterior | 7 | Psoriatic skin lesions, arthritis | — | — |

| Reactive arthritis | Anterior | 7 | Sacroiliitis, keratoderma blennorrhagicum, oral-genital ulcers | — | — |

| Relapsing polychondritis | Anterior | Unknown | Inflammation of cartilaginous tissues | — | Often associated with scleritis, spillover inflammation |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Usually anterior, spillover from scleritis or peripheral keratitis | < 5 | Usually signs of extra-articular disease | Rheumatoid factor | Often associated with scleritis or peripheral keratitis |

| Sarcoidosis | Any location | Unknown | Varies depending on organ system involved | Chest radiography or CT; serum ACE level | Conjunctival biopsy variable yield but low risk |

| Syphilis | Any location | < 5 | Varies depending on stage and immune status | Syphilis serology; CSF-VDRL test | Nontreponemal and treponemal serologic tests are needed |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Any location | < 1 | Skin lesions, renal disease, multiple organ involvement possible | ANA or anti-dsDNA antibodies | — |

| Toxocariasis | Posterior | Unknown | Isolated eye problem not associated with visceral larvae stage of infection | ELISA titer > 1:8; peripheral eosinophilia occasionally noted | Unilateral; usually occurs before 14 years of age; ova and parasite examination has no value |

| Tuberculosis | Any location | < 1 | Varies depending on immune status | PPD skin test; interferon gamma release assay; chest radiography | Consider if patients traveled where disease is endemic |

| Tubular interstitial nephritis | Anterior | Unknown | Fever, arthralgias, rash, nephritis | Urinalysis, renal function studies | Ocular symptoms can precede renal disease |

| Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome | Posterior | 100 | Vitiligo, poliosis, alopecia, meningismus, tinnitus | Lumbar puncture for pleocytosis | Probable autoimmune disease; incidence varies worldwide |

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of uveitis are nonspecific, consisting of various combinations of blurred or reduced vision, visual floaters, eye discomfort or pain, and intolerance to light. Secondary headache or brow ache is common. Occasionally, a patient has no symptoms to report, which is more common in children. The onset of uveitis can be sudden or insidious. The clinical distinction between acute and chronic uveitis has been arbitrarily set at three months. Recurrent uveitis is defined as repeat episodes occurring after three months of disease inactivity without treatment.1

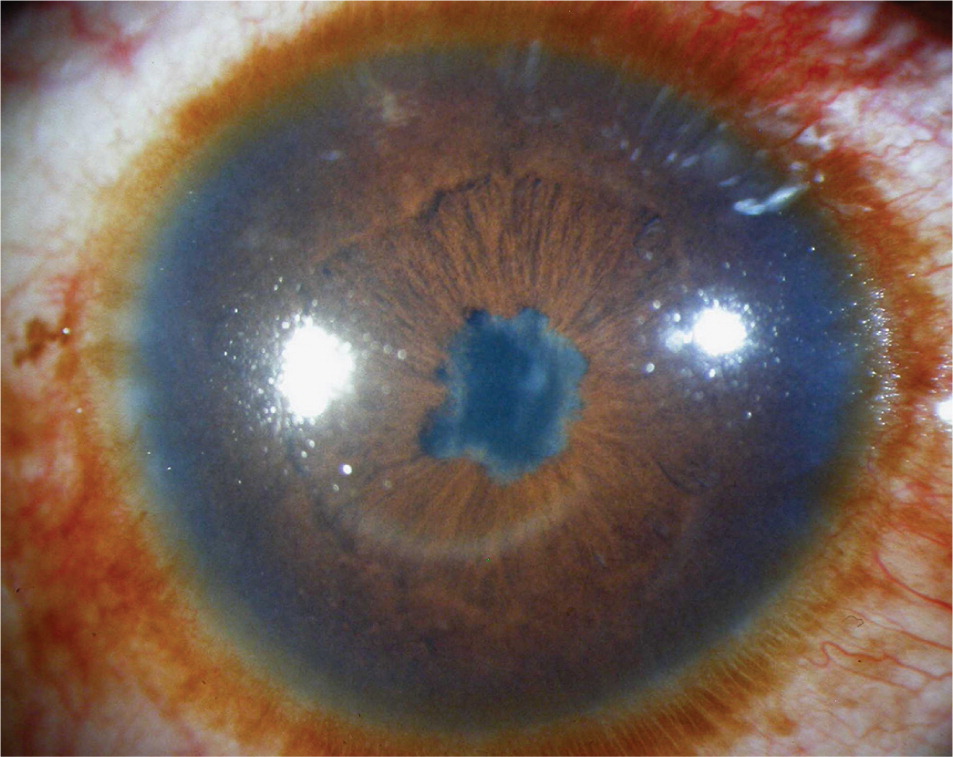

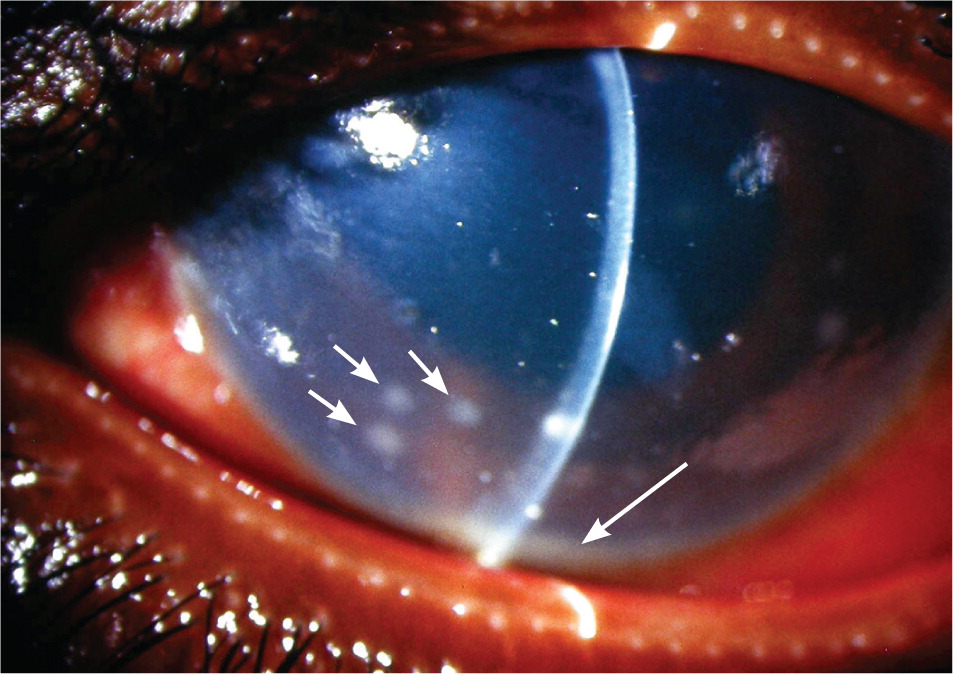

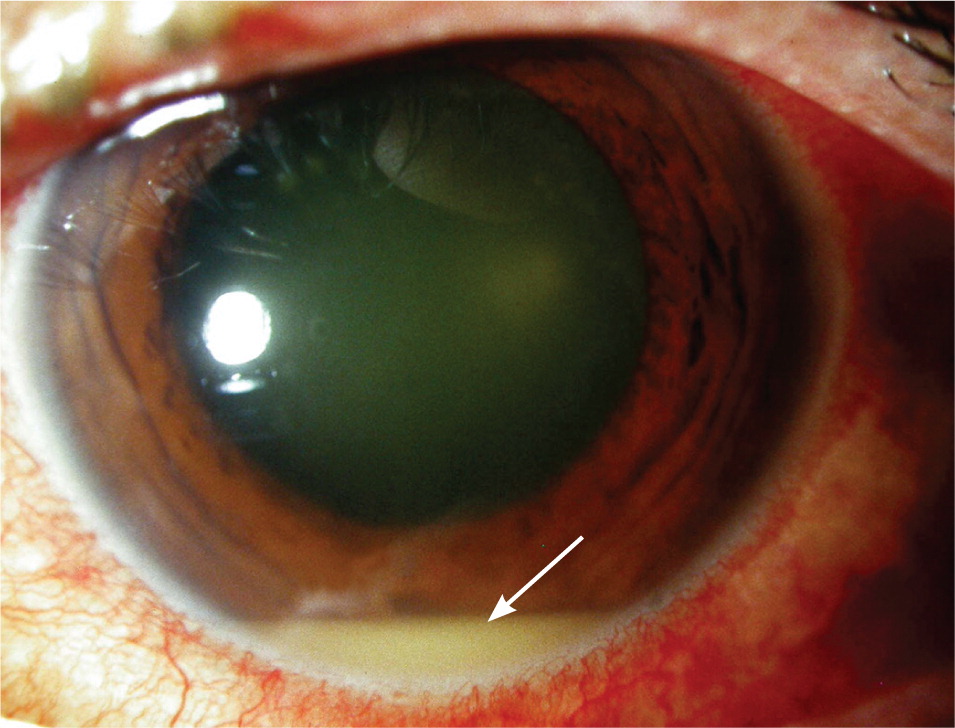

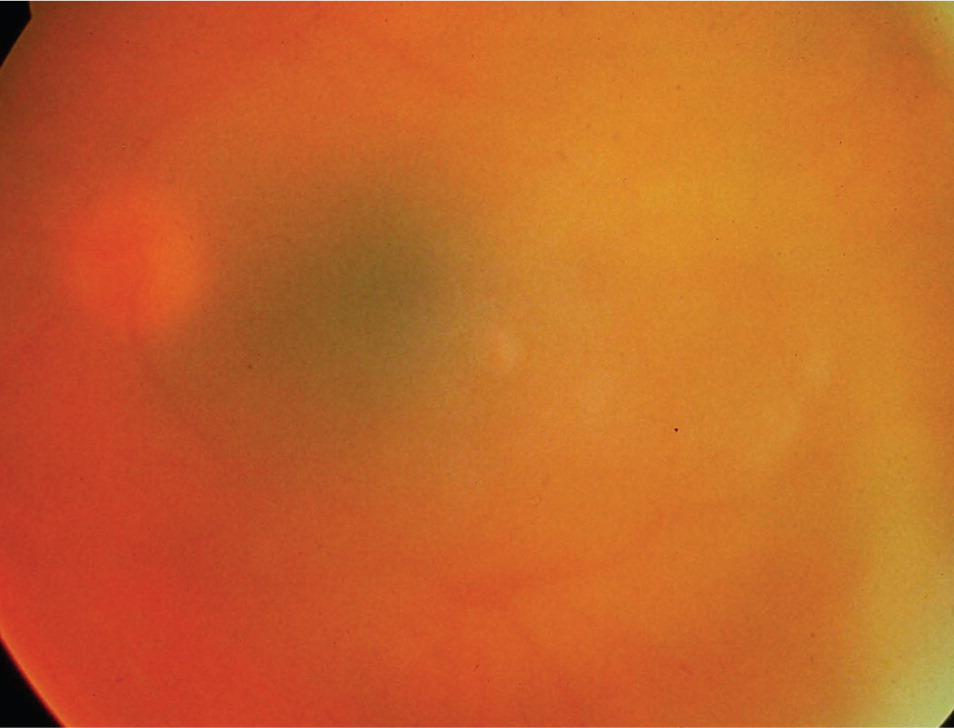

Most eyes with anterior uveitis display conjunctival injection, often associated with a blush of limbal vessels. The iris may be difficult to visualize clearly because of corneal edema or cells and protein suspended in the aqueous. Pupils may react poorly to light if the iris has become adherent to the anterior lens capsule (Figure 2). Occasionally, large clumps of inflammatory cells can be seen on the back surface of the cornea (Figure 3). When inflammation is severe, white blood cells settle in the anterior chamber forming a white interface with the overlying aqueous, a condition referred to as hypopyon (Figure 4). Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and anterior uveitis tend to have deceptively quiet eyes despite considerable inflammation internally. Intermediate and posterior uveitis can present with little or no evidence of inflammation on the surface of the eye. The accumulation of inflammatory cells and protein flare in the vitreous prevents clear inspection of the retina, as if the view is obscured by fog (Figure 5). Although inflammatory cells suspended in the aqueous or vitreous humors are the diagnostic hallmark of uveitis, they require brightly focused illumination and slit lamp magnification for visualization.

Diagnostic Approach

There is no universally accepted approach to the evaluation of uveitis.3,11,12 If the history, physical examination, and basic laboratory tests do not suggest a specific diagnosis, serologic studies for syphilis and chest radiography for sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are recommended2,3,11 (Table 19,10 ). Basic laboratory studies include complete blood count with differential, basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. However, adults who have a single episode of mild anterior uveitis that resolves with a short course of topical corticosteroids, and who have no other suggestive clinical history, usually do not require laboratory studies.13 Typing for human leukocyte antigen-B27 is appropriate for patients with recurrent anterior uveitis, and can be positive in the absence of signs or symptoms of spondylitis. Routine radiology and serologic studies are not indicated for all patients.13–15 Given the relatively low prevalence of many systemic diseases among persons with uveitis, the positive predictive values for Lyme serology, antinuclear antibody, serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, serum lysozyme, and tuberculin skin tests are generally too low to order these studies routinely.14–16

DRUG-INDUCED UVEITIS

Drug-induced uveitis is rare. Symptoms, which overlap those in other forms of uveitis, usually begin days to months after exposure.17–19 Although some drugs can cause concurrent inflammation of the conjunctiva or sclera, drug-induced uveitis essentially mimics infectious and immune-mediated uveitis. For reasons not understood, use of systemic medications can result in unilateral eye involvement. Establishing causal associations can be difficult, and has historically depended on such maneuvers as drug withdrawal and re-challenge.17 Table 2 lists drugs and vaccines that have been associated with uveitis.17–19

| Medication | Site of intraocular inflammation | Risk of uveitis | Onset after exposure | Evidence of association | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-VEGF, intravitreal | Intermediate in treated eye | 1% to 5% of treated eyes | Unknown | Definite | |

| Bisphosphonates | Anterior | < 1% | Days to months | Definite | |

| Brimonidine, topical | Anterior, treated eye | Rare | 11 to 15 months | Definite | |

| Cidofovir (Vistide), intravenous | Anterior | 17% to 89% | Days to weeks | Definite | |

| Cidofovir, intravitreal | Anterior | 26% to 52% | Days to weeks | Definite | |

| Metipranolol (Optipranolol), topical | Anterior, treated eye | Rare | Unknown | Definite | |

| Moxifloxacin (Avelox), oral | Anterior | Rare | 1 to 20 days | Probable | |

| Prostaglandin analogues, topical | Anterior, cystic macular edema, treated eye | 0.9% to 4.9% | Weeks to months | Definite | |

| Rifabutin (Mycobutin) | Any location | 14% to 64% | 2 weeks to 7 months | Definite | |

| Sulfonamides | Anterior | Rare | Days to weeks | Definite | |

| Vaccines | |||||

| Bacille Calmette-Guérin (tuberculosis) | Any location | Rare | Weeks | Definite | |

| Hepatitis B | Any location | Rare | Days | Probable | |

| Influenza | Any location | Rare | Weeks | Probable | |

| Measles, mumps, rubella | Any location | Rare | Weeks | Probable | |

| Varicella | Anterior, posterior | Rare | Unknown | Possible | |

MASQUERADE SYNDROMES AND DIAGNOSTIC CAVEATS

Neoplastic cells may simulate intraocular inflammation. Primary ocular lymphoma should be considered in persons older than 50 years with persistent intermediate or posterior uveitis that does not respond to anti-inflammatory therapy.20

Although intermediate and posterior uveitis caused by bloodborne infection usually occur in the context of severe illness, patients can present with endogenous endophthalmitis and not appear acutely ill. Smoldering intraocular infections can develop secondary to transient septicemia from a fungus or low-virulence bacterium after removal of a chronic indwelling venous catheter or after recreational intravenous drug use. Visual symptoms usually develop days or weeks later when persons are afebrile and may otherwise feel well. Another clinical setting in which persons may not feel seriously ill involves Klebsiella pneumoniae infection; many of these patients also have diabetes mellitus.21 Specific serotypes of Klebsiella have a predilection to seed the eye, even when primary sites of infection appear under control. Delays in diagnosis have resulted in devastating visual outcomes, including loss of an eye.22

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the terms anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, choroiditis, retinochoroiditis, chorioretinitis, and neuroretinitis. Major textbooks of ophthalmology, infectious disease, and rheumatology were reviewed for relevant source material. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology's Basic and Clinical Sciences Course books were also searched. Search dates: June and July 2013; September 2013; and July 2014.