A more recent article on acute stroke diagnosis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(8):528-536

Patient information: See related handout on stroke, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Stroke can be categorized as ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, or subarachnoid hemorrhage. Awakening with or experiencing the abrupt onset of focal neurologic deficits is the hallmark of the diagnosis of ischemic stroke. The most common presenting symptoms of ischemic stroke are speech disturbance and weakness on one-half of the body. The most common conditions that can mimic a stroke are seizure, conversion disorder, migraine headache, and hypoglycemia. Taking a patient history and performing diagnostic studies will usually exclude stroke mimics. Neuroimaging is required to differentiate ischemic stroke from intracerebral hemorrhage, as well as to diagnose entities other than stroke. The choice of neuroimaging depends on availability of the method, the patient's eligibility for thrombolysis, and presence of contraindications. Subarachnoid hemorrhage presents most commonly with sudden onset of a severe headache, and noncontrast head computed tomography is the imaging test of choice. Cerebrospinal fluid inspection for bilirubin is recommended if subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected in a patient with a normal computed tomography result. Public education about common presenting stroke symptoms may improve patient knowledge and clinical outcomes.

The symptoms of acute stroke can be misleading and misinterpreted by clinicians and patients. Family physicians are on the front line to recognize and manage acute cerebrovascular diseases. Rapid, accurate examination of persons with stroke symptoms can reduce disability and help prevent recurrences.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| All patients with stroke symptoms should undergo urgent neuroimaging with CT or MRI. | C | 9, 37 |

| Patients presenting with acute vestibular syndrome or suspected posterior infarction should undergo acute diffusion-weighted MRI. A negative MRI result should be followed by repeat MRI in three to seven days or bedside oculomotor testing to exclude a false-negative result. | C | 18, 37 |

| Lumbar puncture should be performed in persons with suspected subarachnoid hemorrhage and a normal noncontrast head CT result. | C | 22, 23 |

| Patients and family members should be educated about stroke symptoms and the need for urgent evaluation. | C | 9 |

Classifying Stroke

Stroke can be classified by pathologic process and vascular distribution affected. Defining the overall pathologic process is critical for decisions on thrombolysis, antithrombotic therapy, and prognosis. Hemorrhagic stroke has a higher mortality rate than ischemic stroke.1 In the United States, 87% of all strokes are ischemic secondary to large-artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolism, small-vessel occlusion, or other and undetermined causes.1,2 The remaining 13% of strokes are hemorrhagic in intracerebral or subarachnoid locations.1

Risk Factors

Although there are many risk factors for stroke, such as age, family history, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and sleep apnea, the major modifiable risk factors include hypertension, atrial fibrillation, smoking, symptomatic carotid artery disease, and sickle cell disease.1 Physical inactivity; regular consumption of sweetened beverages; and low daily consumption of fish, fruits, or vegetables are also associated with an increased risk of stroke.1 In women, current use of oral contraceptives, migraine with aura, the immediate postpartum period, and preeclampsia confer small absolute increases in risk of stroke.1

Clinical Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

In a community-based study, primary care physicians practicing in an emergency setting had a 92% sensitivity for diagnosing stroke and transient ischemic attack based on history and examination.3 The overall reliability of a clinician's diagnosis of stroke is moderate to good, with lower reliability in less experienced or less confident examiners.4 The most common historical feature of an ischemic stroke is awakening with or acute onset of symptoms, whereas the most common physical findings are unilateral weakness and speech disturbance.5 The most common and reliable symptoms and signs of ischemic stroke are listed in Table 1.4–7 The most common symptoms and signs of posterior circulation stroke are listed in Table 2.8

Figure 1 provides an algorithm for stroke diagnosis. A critical piece of information is the time of onset. This value does not assist in diagnosing stroke, but it determines whether a patient meets the 3- or 4.5-hour eligibility windows for thrombolysis among persons with a diagnosis of ischemic stroke.9

| Symptom or sign | Prevalence (%)5 | Agreement between examiners (kappa)4 |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Acute onset | 96 | Good (0.63)4 |

| Subjective arm weakness* | 63 | Moderate (0.59)4 |

| Subjective leg weakness* | 54 | Moderate (0.59)4 |

| Self-reported speech disturbance | 53 | Good (0.64)4 |

| Subjective facial weakness | 23 | — |

| Arm paresthesia† | 20 | Good (0.62)4 |

| Leg paresthesia† | 17 | Good (0.62)4 |

| Headache | 14 | Good (0.65)4 |

| Nonorthostatic dizziness | 13 | — |

| Signs | ||

| Arm paresis | 69 | Moderate to excellent (0.42 to 1.00)4,6 |

| Leg paresis | 61 | Fair to excellent (0.40 to 0.84)4,6 |

| Dysphasia or dysarthria | 57 | Moderate to excellent (0.54 to 0.84)4,6 |

| Fair to excellent (0.29 to 1.00)4,6 | ||

| Hemiparetic/ataxic gait | 53 | Excellent (0.91)6 |

| Facial paresis | 45 | Poor to excellent (0.13 to 1.00)4,6 |

| Eye movement abnormality | 27 | Fair to excellent (0.33 to 1.00)6 |

| Visual field defect | 24 | Poor to excellent (0.16 to 0.81)4,6 |

| Symptom or sign | Prevalence (%)8 |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Dizziness | 47 |

| Unilateral limb weakness | 41 |

| Dysarthria | 31 |

| Headache | 28 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 27 |

| Signs | |

| Unilateral limb weakness | 38 |

| Gait ataxia | 31 |

| Unilateral limb ataxia | 30 |

| Dysarthria | 28 |

| Nystagmus | 24 |

Physicians managing acute stroke should become familiar with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). The NIHSS is a 15-item scale that can be performed in about five minutes. Although it can help distinguish stroke from stroke mimics,10 its chief use is to reliably evaluate stroke severity to determine whether tissue plasminogen activator administration is appropriate. It is also used to predict prognosis. Reliable use of the NIHSS requires training,11 which can produce excellent inter-rater reliability of scoring across physicians and nurses.12 Free online training is available from the National Stroke Association at http://www.stroke.org/site/PageServer?pagename=nihss.13

Studies of missed stroke diagnosis have found weakness and fatigue, altered mental status, syncope, altered gait and dizziness, and hypertensive urgency to be the most common presenting symptoms in patients admitted for a diagnosis other than stroke who were later confirmed to have had a stroke.14,15 However, such nonspecific symptoms are not usual presentations of stroke. The history and physical examination for common stroke symptoms should uncover the diagnosis of stroke even in uncommon presentations.

Posterior circulation strokes may be challenging to diagnose. One potential area of confusion is when patients present with dizziness, which is a common concern in general but an uncommon presentation for stroke. In a population-based study of adults older than 44 years presenting to the emergency department or directly admitted to the hospital with a principal concern of dizziness, only 0.7% of patients with isolated dizziness symptoms had an ultimate diagnosis of stroke or transient ischemic attack, although their stroke was missed by the initial examiner 44% of the time.16

However, in patients presenting with acute vestibular syndrome17 defined by one hour or more of acute, persistent, continuous vertigo or dizziness with spontaneous or gaze-evoked nystagmus, plus nausea or vomiting, head motion intolerance, and new gait unsteadiness, one-fourth or more have a posterior circulation stroke.18,19 As many as two-thirds of patients with acute vestibular syndrome caused by stroke have no obvious neurologic findings.19 A battery of three bedside tests of eye movement is more sensitive than early magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for diagnosing posterior stroke in this setting and is highly specific.18,20 Table 3 describes the conduct and operating characteristics of each test and the battery.18–20 A video demonstrating these tests is available at http://content.lib.utah.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/ehsl-dent/id/6/rec/5.

| Bedside diagnostic predictor | Test description | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | LR+(95% CI) | LR−(95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal result on horizontal head impulse test | Turn the patient's head laterally 10 to 20 degrees while observing his or her eyes. A normal result is for the eyes to stay fixed on a target. An abnormal result is for the eyes to rapidly move back to the target once head movement stops. The test also may be performed by turning the patient's head back to center from 10 to 20 degrees off-center.20 | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.91) | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 18.39 (6.08 to 55.64) | 0.16 (0.11 to 0.23) |

| Direction-changing nystagmus | Nystagmus in the setting of acute vertiginous syndrome is normally unidirectional, with the fast beat of nystagmus away from the affected side and a slow return toward the affected side. Nystagmus is enhanced when the eye moves toward the side of the fast beat and decreases or disappears when the eye moves toward the side of slow beat. With central lesions, the fast beat of nystagmus may change directions toward the direction the eyes are moving, hence the term “direction-changing nystagmus.”20 | 0.38 (0.32 to 0.44) | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 4.51 (2.18 to 9.34) | 0.68 (0.60 to 0.76) |

| Skew deviation | Normally during the cover-uncover test there is no eye movement. Upward or downward movement on the cover-uncover test (refixation) indicates skew deviation and is associated with a central lesion.20 | 0.30 (0.22 to 0.39) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00) | 19.66 (2.76 to 140.15) | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.80) |

| HINTS positive | HINTS positive is a normal head impulse test result, direction-changing nystagmus, refixation on cover test (skew deviation), or any combination of these findings.18 | 96.8 (92.4 to 99.0) | 98.5 (92.8 to 99.9) | 63.9 (9.13 to 446.85) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.09) |

Reliably distinguishing between hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke can be done only through neuroimaging. Patients with hemorrhagic stroke are more likely to have headache, vomiting, diastolic blood pressure greater than 110 mm Hg, meningismus, or coma, but none of these findings alone or in combination is reliable enough to ascertain a diagnosis.21

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) presents differently from intracerebral hemorrhage or ischemic stroke. About 80% of patients with aneurysmal SAH report a sudden onset of what they describe as the worst headache of their life.22 A previous sentinel headache two to eight weeks before aneurysmal rupture is a critical historical finding present in up to 40% of patients with SAH.22 Findings accompanying the headache can include vomiting, photophobia, seizures, meningismus, focal neurologic signs, and decreased level of consciousness.22,23 Funduscopy should be performed because intraocular hemorrhages are present in one in seven patients with aneurysmal SAH.24 Because the bleeding occurs outside the brain, persons with SAH may not have focal neurologic signs.

STROKE MIMICS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Clinicians should consider a broad differential diagnosis when evaluating suspected stroke (Table 47,9,10,16,19,25–34 ). Seizure, conversion or somatoform disorder, migraine headache, and hypoglycemia are the most common stroke mimics.10,25–30 Checklists to ascertain eligibility for intravenous thrombolysis explicitly include detection of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and recent seizures.

| Condition | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

The rates of misdiagnosis of stroke in studies of consecutive patients not treated with thrombolysis vary from 25% to 31%.10,25,35 Of patients receiving thrombolysis, 1.4% to 16.7% are found to have a stroke mimic.26–31 Factors associated with greater risk of a stroke mimic are younger age, lower baseline NIHSS scores, history of cognitive impairment, and nonneurologic abnormal physical findings.10,26–31 Patients with a stroke mimic are more likely to present with global aphasia without hemiparesis than patients demonstrated to have a stroke.26,31

Diagnostic Tests and Imaging

Table 5 lists initial diagnostic studies recommended by current guidelines for patients with suspected stroke.9 The purpose of these studies is to uncover stroke mimics, diagnose critical comorbidities such as myocardial ischemia, and detect contraindications to thrombolytic therapy. No combination of stroke biomarkers has been shown to give additional diagnostic certainty over that of clinical history and examination alone.36

| All patients |

| Noncontrast brain CT or brain MRI |

| Blood glucose |

| Oxygen saturation |

| Serum electrolytes/renal function tests* |

| Complete blood count, including platelet count* |

| Markers of cardiac ischemia* |

| Prothrombin time/INR* |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time* |

| ECG* |

| Selected patients |

| TT and/or ECT if it is suspected the patient is taking direct thrombin inhibitors or direct factor Xa inhibitors |

| Hepatic function tests |

| Toxicology screen |

| Blood alcohol level |

| Pregnancy test |

| Arterial blood gas tests (if hypoxemia suspected) |

| Chest radiography (if lung disease suspected) |

| Lumbar puncture (if subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected and CT scan is negative for blood) |

| Electroencephalogram (if seizures are suspected) |

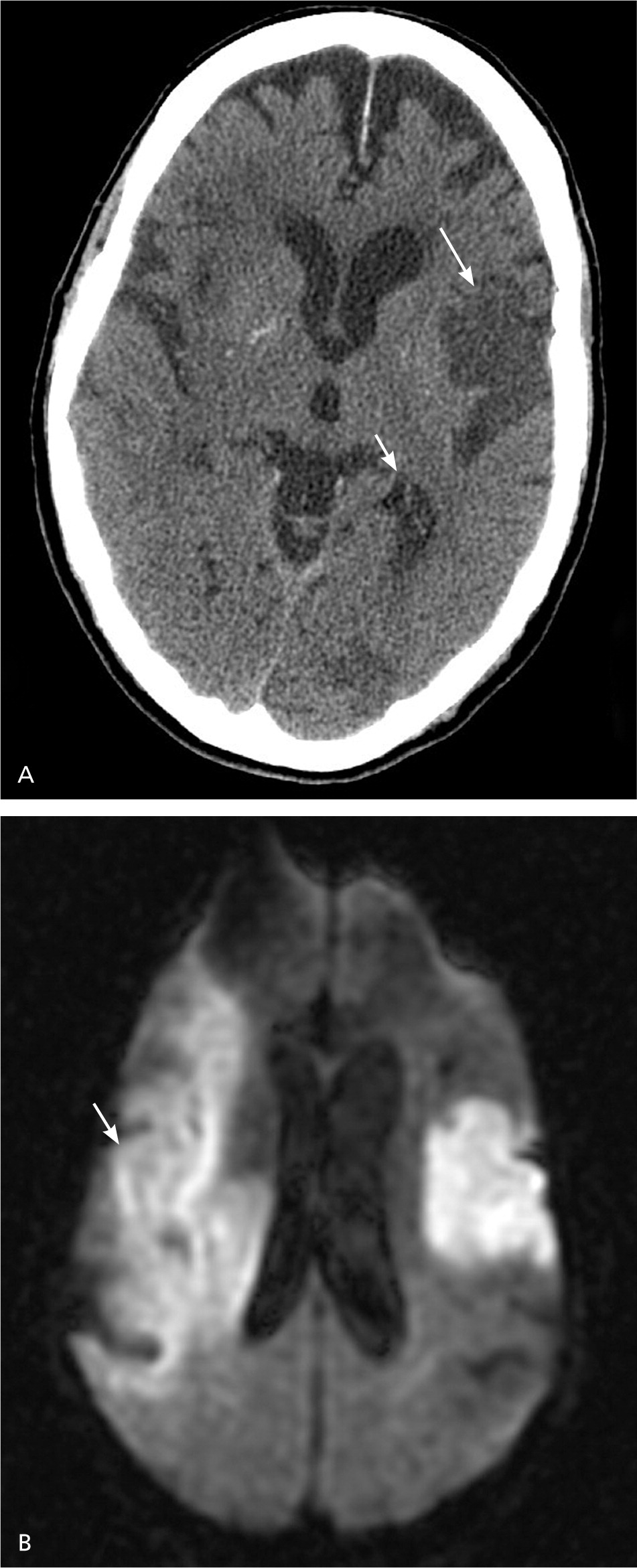

All patients with stroke symptoms should undergo urgent neuroimaging with noncontrast computed tomography (CT) or MRI.9,37 The primary purpose of neuroimaging in a patient with suspected ischemic stroke is to rule out the presence of nonischemic central nervous system lesions and to distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Figures 2 and 3 show examples of intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhages on non-contrast CT.7 Noncontrast CT is considered sufficiently sensitive for detecting mass lesions, such as a brain mass or abscess, as well as for detecting acute hemorrhage. However, less than two-thirds of strokes are detected by noncontrast CT at three hours postinfarction.38 Noncontrast CT has even lower sensitivity for small or posterior fossa strokes.9

Multimodal MRI sequences, particularly diffusion-weighted images, have better resolution than noncontrast CT, and therefore have a greater sensitivity for detecting acute ischemic stroke.37,38 MRI sequences (particularly gradient recalled echo and diffusion-weighted sequences) are as sensitive as noncontrast CT for detecting intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke.9,37,38 Figure 4 shows the head noncontrast CT and diffusion-weighted MRI of a patient with a previous stroke and a new acute stroke.

MRI has better resolution than noncontrast CT, but noncontrast CT is faster, more available, less expensive, and can be performed in persons with implanted devices (e.g., pacemakers) and in persons with claustrophobia. If a patient is within the time window of intravenous thrombolytic therapy, guidelines recommend that noncontrast CT or MRI be performed to exclude intracerebral hemorrhage and evaluate for ischemic changes.9 In patients younger than 55 years presenting with stroke-like symptoms, MRI yields a lower rate of misdiagnosis than noncontrast CT because of a lower prevalence of vascular risk factors and a higher prevalence of central nervous system stroke mimics in this age group.39,40 Patients presenting with acute vestibular syndrome or suspected posterior infarction should undergo acute diffusion-weighted MRI.37 Because MRI may miss up to 15% of posterior strokes in the first 48 hours,18 a negative MRI result should be followed by a repeat MRI in three to seven days or bedside oculomotor testing to exclude a false-negative result.

Although acute neuroimaging is essential, it may be possible to efficiently obtain imaging of the carotid arteries to detect carotid stenosis, such as when MRI of the brain is combined with magnetic resonance angiography of the neck. Current guidelines do not address acute imaging of cervical vessels, but it is recommended as part of the subsequent evaluation of patients with confirmed stroke or transient ischemic attack,9 which is beyond the scope of this article. Acute intracranial vascular imaging is recommended if intravascular therapy is being considered, as long as it does not delay intravenous thrombolysis.9

Unlike ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage, diagnosing SAH requires a different diagnostic approach. The frequency of misdiagnosis of SAH is about 12%.22 Noncontrast CT is the imaging test of choice for persons with suspected SAH.22 Noncontrast CT has a sensitivity of nearly 100% for detecting subarachnoid blood in the first 72 hours.22 The sensitivity of noncontrast CT to detect subarachnoid blood declines over time, whereas MRI remains highly sensitive to intracranial blood for up to 30 days, making it the preferred test for delayed presentations.22,23

Persons with suspected SAH and a normal noncontrast CT result should undergo a lumbar puncture to detect bilirubin, a breakdown product of red blood cells in the cerebrospinal fluid.23 Because red blood cell breakdown can take up to 12 hours, the lumbar puncture should be delayed until 12 hours after the initial onset of symptoms to accurately distinguish SAH from a traumatic tap.23,41 The yellow color caused by bilirubin, which is called xanthochromia, can be detected by visual inspection or spectrophotometry.23,41 Spectrophotometry is more sensitive than visual inspection, but is not widely available.23,41 Bilirubin can be detected up to two weeks after the initial onset of symptoms. If SAH is detected, persons should immediately undergo CT, MRI, or catheter angiography to look for an aneurysm.

Training Patients to Recognize Stroke Symptoms

Patients and family members should be educated about stroke symptoms and the need for urgent evaluation.9 Consistent data show considerable room for improvement in stroke knowledge in the general population.42 However, there are limited data to support the effectiveness of public media campaigns to improve stroke knowledge and to link improved knowledge of stroke symptoms to behavior or clinical outcomes.43,44 A recent study showed that knowledge of two warning signs of stroke was associated with activation of emergency medical services, which suggests a goal for public education campaigns.45 The American Stroke Association is promoting the F.A.S.T. (face drooping, arm weakness, speech difficulty, time to call 9–1–1) campaign to improve patient knowledge about stroke and to expedite activation of 9–1–1 services.46

Data Sources: A PubMed search using a filter for diagnostic studies detailed in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Beynon R, Leeflang MM, McDonald S, et al. Search strategies to identify diagnostic accuracy studies in Medline and Embase. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):MR000022) was performed using the MeSH stroke terms stroke; stroke, lacunar; infarction, posterior cerebral artery; brain stem infarctions; infarction, middle cerebral artery; infarction, anterior cerebral artery; anterior spinal artery stroke crossed with sensitivity and specificity#[MESH] OR diagnos* OR predict* OR accura* with limits of human, English, adult and publication date after June 1, 2008 (the end date of the literature search for the previous AFP article on this topic). Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement “Diagnosis and Initial Treatment of Ischemic Stroke” guideline, 10th ed., and article bibliographies. Search dates: July 10, 2014, and February 13, 2015.

note: This review updates a previous article on this topic by the authors.7

The authors thank Dr. James Smirniotopoulos for assistance with MedPix, and Mrs. Robin Yew for editorial assistance.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

Dr. Cheng received funding from Cooperative Agreement Award U54 NS08164 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.