A more recent article on metabolic surgery for adult obesity is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(1):31-37

Related Close-ups: Making Lifestyle Changes After Gastric Bypass

Patient information: See related handout on weight loss surgery, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

In 2013, approximately 179,000 bariatric surgery procedures were performed in the United States, including the laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (42.1%), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (34.2%), and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (14.0%). Choice of procedure depends on the medical conditions of the patient, patient preference, and expertise of the surgeon. On average, weight loss of 60% to 70% of excess body weight is achieved in the short term, and up to 50% at 10 years. Remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus occurs in 60% to 80% of patients two years after surgery and persists in about 30% of patients 15 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Other obesity-related comorbidities are greatly reduced, and health-related quality of life improves. The Roux-en-Y procedure carries an increased risk of malabsorption sequelae, which can be minimized with nutritional supplementation and surveillance. Overall, these procedures have a mortality risk of less than 0.5%. Cohort studies show that bariatric surgery reduces all-cause mortality by 30% to 50% at seven to 15 years postsurgery compared with patients with obesity who did not have surgery. Dietary changes, such as consuming protein first at every meal, and regular physical activity are critical for patient success after bariatric surgery. The family physician is well positioned to counsel patients about bariatric surgical options, the risks and benefits of surgery, and to provide long-term support and medical management postsurgery.

Obesity is a disease that has serious physical, psychological, and economic implications for patients, and poses major challenges for the physicians caring for them.1 Approximately 35% of the U.S. adult population is obese.2 Obesity affects every organ system (Table 11,3–5 ); the related pathologic processes create a health burden for patients and an economic burden for the health care system. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening all adults for obesity. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg per m2 or higher should be offered or referred to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions.6 These interventions can result in clinically significant weight loss (5% or greater) in patients with obesity and can be initiated by the family physician.6 Surgical treatment of obesity results in greater weight loss, greater reduction in comorbidities, and prolonged survival compared with nonsurgical interventions.3,7–9 Recent emphasis has shifted from weight loss outcomes to the metabolic effects of these surgical procedures.10 Family physicians are well positioned to counsel patients about bariatric surgical options, as well as provide long-term support and medical management postsurgery.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: BARIATRIC SURGERY

Remission of diabetes mellitus occurs in 60% to 80% of patients 1 to 2 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, and remission is retained in approximately 30% of patients at 15 years.

In multiple cohort studies, bariatric surgery is associated with relative reductions in all-cause mortality of 30% to 50% after 7 to 15 years.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bariatric surgery results in greater weight loss than nonsurgical weight loss interventions. | A | 1, 3, 16, 22 |

| Bariatric surgery is highly effective in treating obesity-related comorbidities, particularly diabetes mellitus. | A | 1, 16, 18, 19, 22, 24 |

| Bariatric surgery reduces obesity-related mortality. | B | 1, 7–9, 16, 27 |

| Cardiovascular | Endocrine | Gastrointestinal | Genitourinary | Musculoskeletal | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | Hypoandrogenism | Colorectal cancer | Breast cancer | Chronic low back pain | Dementia |

| Cardiomyopathy | Hypothyroidism | Esophageal cancer | Chronic kidney disease | Immobility | Leukemia |

| Dyslipidemia | Infertility | Gallbladder cancer | Endometrial cancer | Osteoarthritis | Malignant melanoma |

| Hypertension | Metabolic syndrome | Gastroesophageal reflux | Kidney stones | ||

| Long QT syndrome | Pancreatic cancer | Hiatal hernia | Ovarian cancer | ||

| Obstructive sleep apnea | Polycystic ovary syndrome | Irritable bowel syndrome | Prostate cancer | ||

| Thromboembolism | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Liver cancer | Renal cell cancer | ||

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | Urinary incontinence | ||||

Indications and Eligibility

Worldwide, more than 340,000 bariatric procedures were performed in 2011.11 According to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, about 179,000 were performed in the United States in 2013.12 Eligibility criteria were established by the 1991 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel and have changed little in the ensuing years.13 Selection and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 2.10

| Selection criteria |

| Able to adhere to postoperative care (e.g., follow-up visits and tests, medical management, use of dietary supplements) |

| BMI ≥ 40 kg per m2 without coexisting medical conditions |

| BMI ≥ 35 kg per m2 and one or more severe obesity-related comorbidities |

| BMI 30 to 34.9 kg per m2 with diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome (evidence is limited) |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Cardiopulmonary disease that would make the risk prohibitive |

| Current drug or alcohol abuse |

| Lack of comprehension of risks, benefits, expected outcomes, alternatives, and required lifestyle changes |

| Reversible endocrine or other disorders that can cause obesity |

| Uncontrolled severe psychiatric illness |

Preoperative Considerations

Evaluation of the surgical candidate is often conducted by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in nutrition, psychology or psychiatry, surgery, and medicine. Components of the preoperative evaluation are described in a 2013 clinical practice guideline from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (Table 3).10 In practice, third-party payers and surgeon preference often determine the scope of presurgical evaluation and preparation.

| Recommended measures |

| Age- and risk-appropriate cancer screening |

| Complete history and physical examination (e.g., assess comorbidities, weight loss history, commitment to postsurgical lifestyle modifications, exclusions for surgery) |

| Laboratory studies* (e.g., A1C level, complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, folic acid, iron studies, lipid profile, prothrombin time, urinalysis, vitamin B12, 25-hydroxyvitamin D), additional evaluation as indicated |

| Nutrition evaluation |

| Pregnancy counseling† |

| Psychosocial and behavioral evaluations |

| Tobacco cessation counseling for optimal wound healing |

| Additional evaluations to consider |

| Cardiopulmonary evaluation (e.g., polysomnography, electrocardiography, additional evaluation if cardiac disease or pulmonary hypertension suspected) |

| Gastrointestinal evaluation (Helicobacter pylori screening in high-prevalence areas; gallbladder evaluation, upper endoscopy if clinically indicated) |

The patient evaluation should include a complete history and physical examination with attention to obesity-related comorbidities and weight loss–attempt history; three to six months of medical weight management; psychosocial, behavioral, and nutrition evaluations; and appropriate laboratory studies. The purpose of this evaluation is to identify and optimally manage conditions that may negatively affect the perioperative period and increase morbidity. Because patients with obesity may avoid preventive medical visits, age- and risk-appropriate cancer screening should be performed at this time.10 In high-risk patients with an enlarged or fatty liver, preoperative weight loss can reduce liver volume and, therefore, may improve the technical aspects of the surgery.

Choice of Procedure

Most bariatric surgeries are performed laparoscopically; this is preferred to open procedures because of decreased mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and more rapid recovery.14 Currently, three procedures are commonly performed: laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

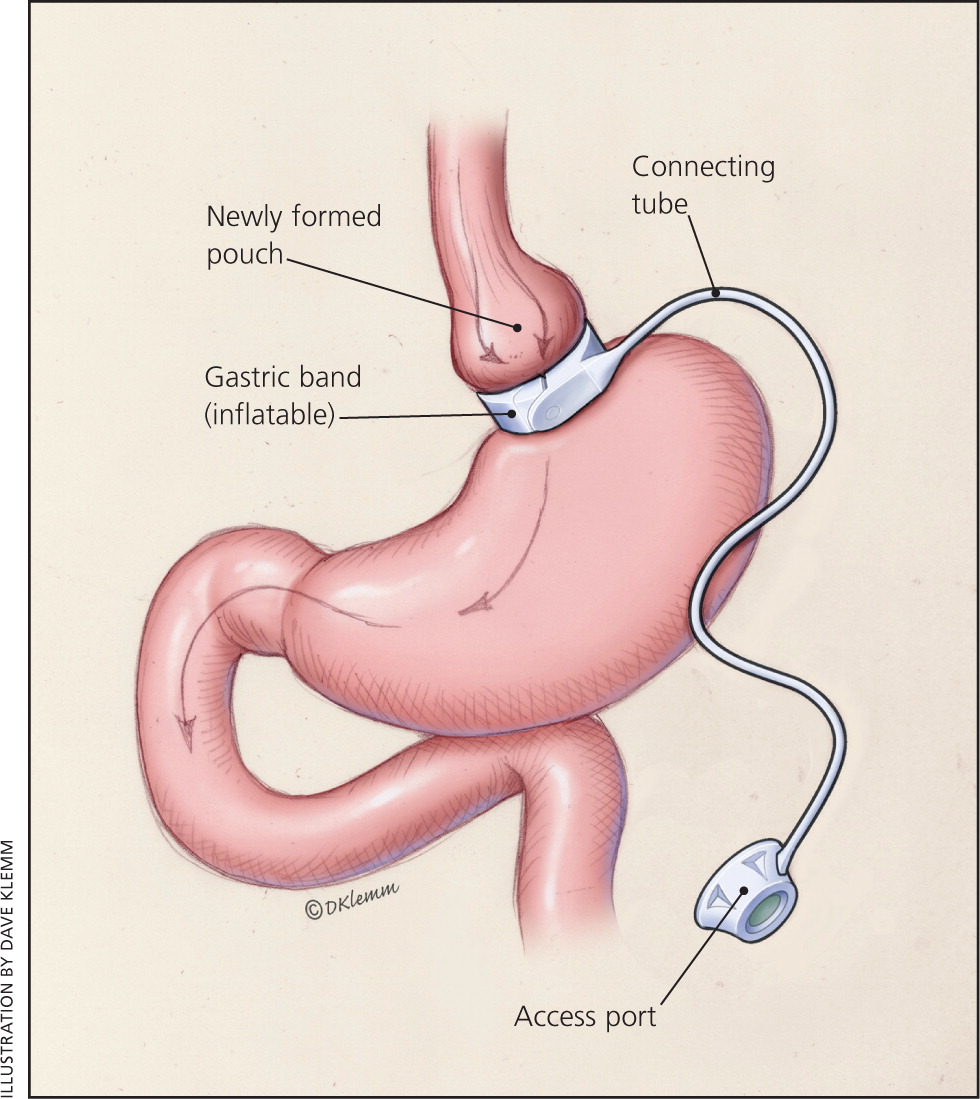

LAPAROSCOPIC ADJUSTABLE GASTRIC BANDING

In laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, a hollow, flexible silicone band is placed around the upper stomach, which causes a restrictive effect, reduces stomach capacity, and produces rapid feelings of satiety. The band is tightened by injecting saline into it through a subcutaneous port, which is located just inferior to the sternum or lateral to the umbilicus (Figure 115 ). Because of a higher complication rate and less weight loss compared with the other two most common procedures, the demand for gastric banding is decreasing in the United States.16

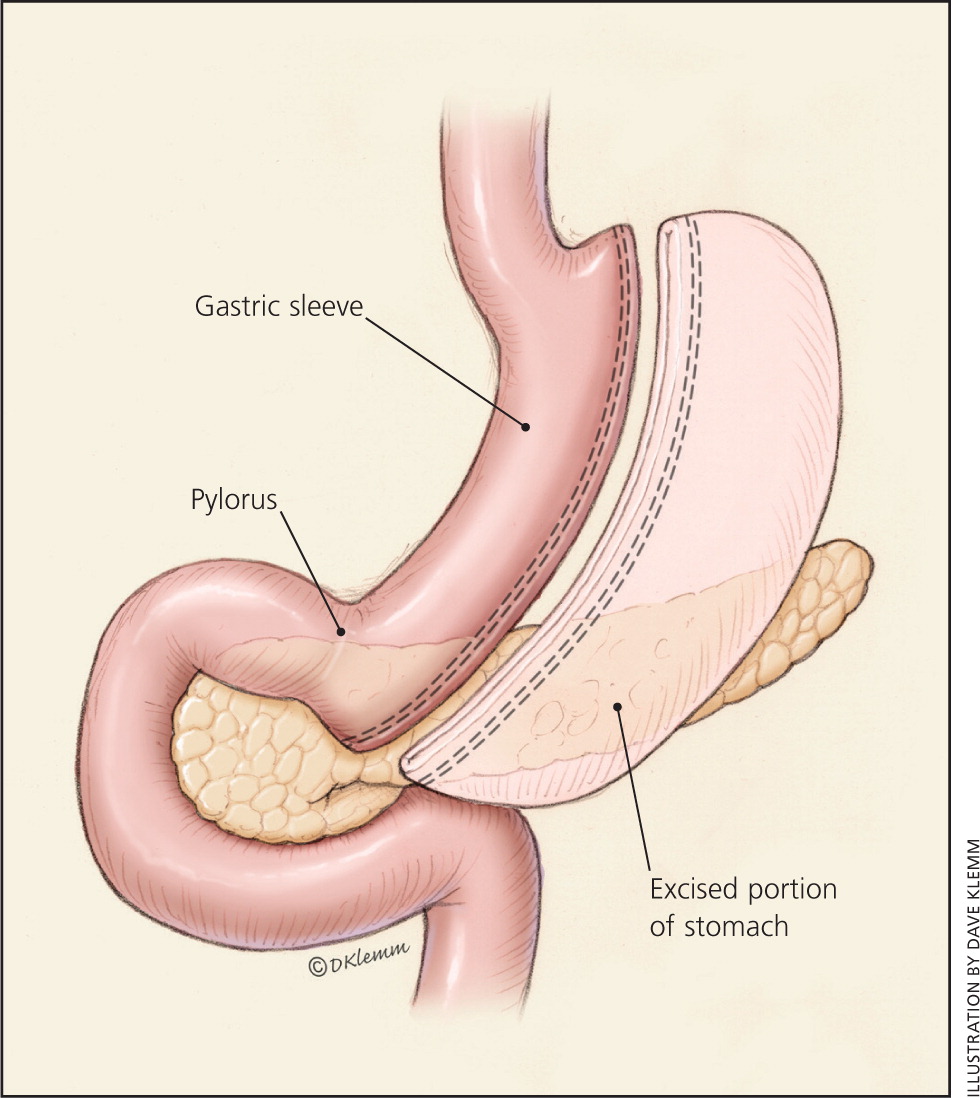

LAPAROSCOPIC SLEEVE GASTRECTOMY

The laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy resects most of the body and all of the fundus of the stomach, creating a long, narrow, tubular stomach (Figure 215 ). This procedure was first used as an initial step before a malabsorptive procedure in very high-risk patients, but is now used as a primary stand-alone procedure and is increasing in popularity.17

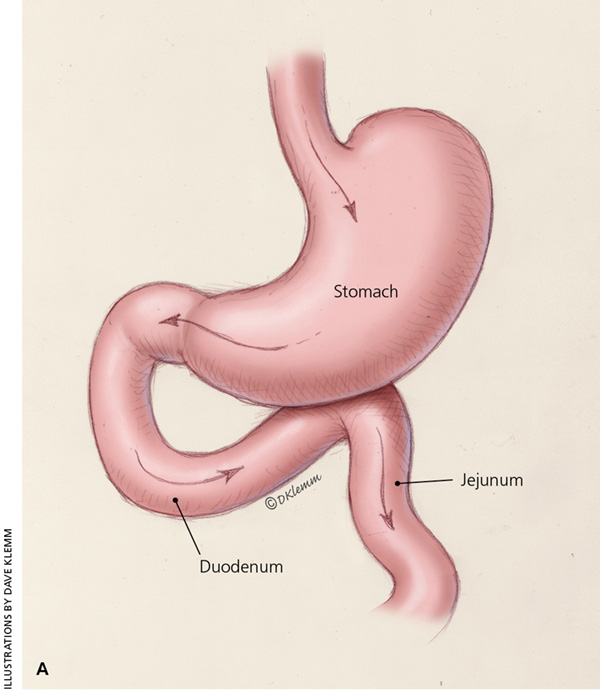

ROUX-EN-Y GASTRIC BYPASS

In Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, a small gastric pouch is formed by dividing the upper stomach and joining it with the resected end of the jejunum, so that food bypasses the stomach and upper small bowel, thereby restricting the size of the stomach and causing some malabsorption (Figure 315 ). Roux-en-Y gastric bypass may be a better choice in patients who are more obese and in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus.18,19

The choice of procedure depends on patient preference, the expertise of the surgeon and surgical center, and risk stratification.10

In 2013, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was reported to be the most common procedure (42.1%), followed by Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (34.2%) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (14.0%). Six percent of surgeries were for revision of a previous procedure.12

Pathophysiology

These surgical procedures were previously conceptualized as restrictive (create a much smaller stomach), malabsorptive (bypass normal anatomy), or a combination. Research now indicates that the mechanisms of action include multiple physiologic variables that affect endocrine and neuronal signaling.20 Improvements in blood glucose levels, dyslipidemia, and other obesity-related comorbidities occur earlier than can be fully explained by the actual weight loss.

In addition to decreased caloric intake, multiple mechanisms contribute to the dramatic improvement of type 2 diabetes after procedures that alter gastrointestinal anatomy. Levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY, which are secreted by intestinal L cells, increase after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy procedures. Glucagon-like peptide-1 enhances insulin secretion, whereas peptide YY increases satiety and delays gastric emptying through receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Ghrelin, secreted primarily by the gastric fundus and proximal small intestine, acts via the hypothalamus to stimulate appetite and suppress energy expenditure and fat catabolism. Procedures that bypass the gastric fundus seem to reduce the secretion of ghrelin and reduce appetite. Neurotransmitters and hormones of the gut, brain, central and peripheral nervous systems, and adipocytes interact in a complex neuroendocrine system to regulate energy homeostasis.20

Postoperative Management

The bariatric surgeon generally provides early postoperative management, including surveillance for complications. The progression of diet from clear liquids to regular food over the first four weeks is facilitated by consultation with a dietician.10

After bariatric surgery, patients are encouraged to eat and journal three structured meals and one or two high-protein snacks per day. Each meal should begin with protein to ensure adequate intake of 80 to 90 g per day to minimize the loss of lean body mass. Food intolerances are patient specific, but very dry foods, bread, and fibrous vegetables are often problematic. Patients should be advised to eat slowly and chew thoroughly. Fluids should be avoided for 15 to 30 minutes before, during, and after meals because ingested food will pass easily through the pouch opening if it is mixed with fluid, and sensation of fullness will not be achieved. Carbonated beverages should be avoided because of the added gas. Cold intolerance, hair loss, and fatigue are common but tend to diminish rapidly as weight loss stabilizes.

All patients who have had weight loss surgery should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and smoking because they increase the risk of anastomotic ulcerations. Women should avoid becoming pregnant for 12 to 18 months after surgery. This period of rapid weight loss may increase the risk of nutritional deficiencies and small-for-gestational-age status in infants (Table 4).10 Continued lifestyle modification is necessary, including regular physical activity and individualized behavioral interventions to address food impulse control. Ongoing participation in postsurgical support groups is highly recommended.

| Adjust postoperative medications, as needed |

| Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Avoid pregnancy for 12 to 18 months |

| Bone density measurement with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry at 2 years |

| Laboratory studies (e.g., complete blood count, complete metabolic profile, folic acid, iron studies, intact parathyroid hormone level, lipid profile, vitamin B12, 24-hour urinary calcium excretion, 25-hydroxyvitamin D) |

| Monitor adherence to dietary, behavioral, and physical activity recommendations |

Quarterly assessment of nutritional status and supplementation needs, food intolerances, and procedure-related symptoms should occur for the first year after bariatric surgery. A variety of micronutrient deficiencies have been identified after malabsorption procedures and even after some restrictive procedures because of decreased capacity for food intake. Vitamin supplementation will likely be required throughout the patient's lifetime, and annual metabolic and nutritional monitoring is recommended (Table 5).10

| Supplement | Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium citrate | 1,200 to 1,500 mg per day | 1,200 to 1,500 mg per day | 1,500 to 2,000 mg per day | Split doses; monitor for osteoporosis |

| Elemental iron | 45 to 60 mg per day, including multivitamin | 45 to 60 mg per day, including multivitamin | 45 to 60 mg per day, including multivitamin | Take iron and calcium supplements at least 2 hours apart |

| Multivitamin with minerals (including iron, folic acid, copper, and thiamine) | 1 per day | 2 per day | 2 per day | Liquid or chewable for 3 to 6 months |

| Vitamin B12 | 1,000 mcg per day | 1,000 mcg per day | 1,000 mcg per day | Sublingual, subcutaneous intramuscular, or oral, if adequately absorbed |

| Vitamin D3 | At least 3,000 IU per day | At least 3,000 IU per day | At least 3,000 IU per day | Titrate to 25-hydroxyvitamin D level greater than 30 ng per mL (75 nmol per L) |

Effectiveness

Summarizing and quantifying the comparative outcomes of bariatric surgery have been challenging because of the evolution of surgical procedures, the availability of laparoscopic vs. open techniques, categorization of short- vs. long-term sequelae, and the difference in presurgical risk among patients.3,16,21–23 The National Institutes of Health–initiated Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Consortium is conducting prospective, multicenter, cohort studies using standardized techniques to assess the safety and clinical response of bariatric surgery.22

In general, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass seems to lead to the greatest weight loss during the first two postsurgical years, followed by laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. It is unclear if there is a significant long-term difference in weight loss between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (Table 67–10,16,18,19,21–27 ). Increasing evidence that laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding results in more long-term complications, more reoperations, and less weight loss has made this procedure less common.28 Dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and perception of quality of life improved after weight loss surgery.3,21

| Outcome | Overall | Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median excess body weight lost (%)* | ||||

| 1 to 2 years | 60 to 70 | 29 to 56 | 33 to 85 | 48 to 85 |

| 3 to 6 years | 50 to 60 | 39 to 72 | 46 to 66 | 53 to 77 |

| 7 to 10 years | 50 | 14 to 60 | — | 25 to 68 |

| Remission of diabetes mellitus (%) | ||||

| < 1 year | 80 | 27 to 29 | 56 to 68 | 56 to 84 |

| 1 to 3 years | 72 | 28 | 80 | 46 to 81 |

| 15 years | 30 | — | — | — |

| Mortality (%) | ||||

| ≤ 30 days | 0.08 | 0.02 to 0.07 | 0.296 | 0.20 to 0.50 |

| > 30 days | 0.31 | 0.21 to 0.50 | 0.11 to 0.34 | 0.14 to 0.21 |

| 7 to 15 years | 30% to 50% lower than those not having surgery | |||

Remission of type 2 diabetes occurs in 60% to 80% of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients at one to two years postsurgery.18,23-25 Recent longer-term studies indicate that this remission is retained in approximately 40% of patients at 10 years and 30% at 15 years.9,19 Several recent reviews support bariatric surgery for the treatment of diabetes in patients with a BMI less than 35 kg per m2.26

The Swedish Obese Subjects prospective cohort study found that surgery was associated with a 29% lower mortality risk from any cause after 16 years.8 In a retrospective cohort study of almost 8,000 patients undergoing bariatric surgery, mortality from disease, including cardiovascular disease and cancer, decreased by 40% compared with the control group.7 In a more recent retrospective cohort study of 2,500 surgical patients and 7,462 matched controls receiving care in the Veterans Administration system, the surgical patients had a significant reduction in 10-year all-cause mortality.27

Weight regain is a concern in a subset of patients following weight loss surgery; the etiology appears to be multifactorial. A systematic review from 2013 identified nutritional indiscretion, mental health issues, endocrine and metabolic alterations, physical inactivity, and anatomic surgical failure as principal causes.29 Endoscopic or surgical revision is an option in some patients who experience weight regain. Further study is necessary to determine predictors of suboptimal weight loss and weight regain, as well as the effectiveness of treatment with surgical revision or other modalities.28–30

Cost

It is estimated that obesity accounts for 16.5% of all medical spending, an estimated $168 billion per year direct cost to the health care system.31 Whether bariatric surgery procedures are ultimately cost-effective or cost saving requires additional long-term study. Measures of improved health and well-being, with direct costs of bariatric surgery and subsequent health care costs, must be compared with those for patients with obesity who do not have surgery to allow for better informed decisions in the future.31–33

Data Sources: The following resources were reviewed: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. References from key articles were also searched. In addition, an OVID Medline search was performed using the keywords obesity, bariatric weight loss, surgery, and diabetes. Search dates: October 2014 and February 2015.

note: This review updates a previous article on this topic by Schroeder, Garrison, and Johnson.15