A more recent article on glaucoma is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(8):668-674

Author disclosure: The authors report that the development of this article was supported in part by an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Glaucoma is a set of irreversible, progressive optic neuropathies that can lead to severe visual field loss and blindness. The two most common forms of glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma and primary angle-closure glaucoma, affect more than 2 million Americans and are increasing in prevalence. Many patients with glaucoma are asymptomatic and do not know they have the disease. Risk factors for primary open-angle glaucoma include older age, black race, Hispanic origin, family history of glaucoma, and diabetes mellitus. Risk factors for primary angle-closure glaucoma include older age, Asian descent, and female sex. Advanced disease at initial presentation and treatment nonadherence put patients with glaucoma at risk of disease progression to blindness. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has concluded that the evidence is insufficient to assess the potential benefits and harms of screening for glaucoma in the primary care setting. Regular eye examinations for adults are recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, with the interval depending on patient age and risk factors. Diagnosis of glaucoma requires careful optic nerve evaluation and functional studies assessing a patient's visual field. The goal of treatment with eye drops, laser therapy, or surgery is to slow visual field loss by lowering intraocular pressure. Family physicians can contribute to lowering morbidity from glaucoma through early identification of high-risk patients and by emphasizing treatment adherence in patients with glaucoma.

Glaucoma is a group of optic neuropathies associated with characteristic structural changes at the optic nerve head that may lead to visual field loss and, ultimately, blindness. Blindness is most commonly defined as 20/200 or worse visual acuity on a Snellen eye chart or a visual field of less than 20 degrees. Legal blindness refers to the fulfillment of these criteria by the better-seeing eye. By 2020, approximately 79.6 million persons worldwide will have glaucoma and more than 11 million will be bilaterally blind from glaucoma.1 More than 2 million Americans 40 years and older have glaucoma, and studies of the U.S. population estimate that more than one-half of these cases may be undiagnosed or untreated.2,3 Among black and Hispanic persons, glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness. Glaucoma accounts for more than 25% of cases of blindness in these groups, making it a more common cause of blindness than diabetic retinopathy (accounting for 7.3% and 14.3% of cases in blacks and Hispanics, respectively) and age-related macular degeneration (accounting for 4.4% and 14.3% of cases in blacks and Hispanics, respectively). Among Hispanics, glaucoma causes blindness more often than cataracts do (28.6% vs. 14.3%).4 In 2009, Medicare beneficiaries spent $748 million on glaucoma-related visits, testing, and procedures.5 Patients with glaucoma who are not blind may have functional limitations, leading to driving cessation and decreased ability to read.6

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: GLAUCOMA

Recent meta-analyses have concluded that diabetes mellitus is associated with a greater risk of developing primary open-angle glaucoma and higher intraocular pressure.

The U.K. Glaucoma Treatment Study (a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial) recently showed longer visual field preservation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma taking latanoprost (Xalatan).

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Fundus photography or intraocular pressure measurement alone is a poor screening tool to detect patients with glaucoma. | C | 22 |

| Family history of open-angle glaucoma, older age, and black race or Hispanic origin are important risk factors for open-angle glaucoma. | C | 1, 31, 32, 36, 37, 44–48, 50, 51 |

| Early treatment of patients with glaucoma reduces the risk of visual field progression. | B | 8 |

The two most common forms of glaucoma are primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG), with the former approximately seven times more common than the latter in the United States and Europe.1 When POAG and PACG are left untreated, the typical disease course is chronic, progressive, and irreversible visual field loss, which may progress to tunnel vision and, ultimately, loss of central vision. Treatment that reduces intraocular pressure has been shown to improve outcomes in randomized clinical trials.7–10

Many patients with glaucoma remain asymptomatic, even as the disease advances, because progressive visual field loss is peripheral and typically asymmetric, which allows for compensation from the overlapping, less-affected visual field of the other eye. As a result, POAG is often found incidentally on ocular examination.

Although the prevalence of glaucoma increases with age, most patients with undetected glaucoma are younger than 60 years, which represents an opportunity to diagnose the disease earlier.3 This article reviews the pathophysiology of and risk factors for glaucoma, and emphasizes the role of family physicians in the care of affected patients.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

OPEN-ANGLE GLAUCOMA

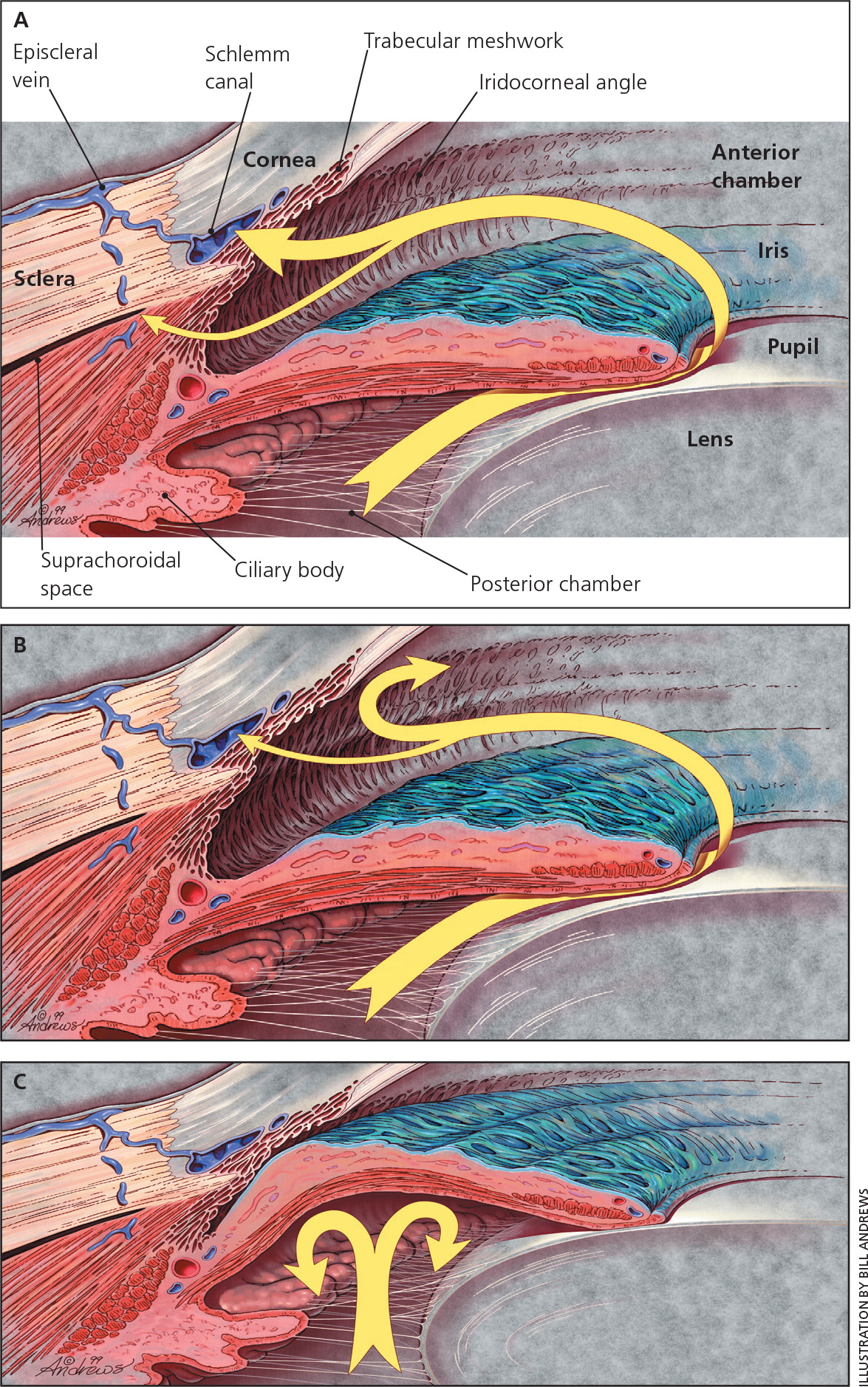

The angle of the eye is the junction between the iris and cornea, where the trabecular meshwork drains aqueous humor from the anterior chamber of the eye (Figure 1).11 In POAG, the angle remains open as the trabecular meshwork is unblocked by iris tissue. Intraocular pressure is transmitted to the axons of retinal ganglion cells at the optic nerve as mechanical stress, leading to cell death.12 However, about 50% of patients with glaucoma have intraocular pressure within the so-called “normal” range of 10 to 21 mm Hg at diagnosis.8 Only after 30% of retinal ganglion cells have been lost are visual field defects present on perimetric testing.13,14

ANGLE-CLOSURE GLAUCOMA

In PACG, the peripheral iris obstructs normal aqueous outflow (Figure 1).11 This can lead to increased intraocular pressure and optic nerve damage. Eyes that are at risk of PACG tend to be shorter with a shallower anterior chamber.15 Patients with PACG may experience acute or subacute events that occur after a sudden rise in intraocular pressure or from chronic PACG that is insidious in onset and largely asymptomatic.

In the rare event of acute angle closure, patients experience sudden and possibly painful loss of vision due to acutely elevated intraocular pressure.16 Symptoms include unilateral (rarely bilateral) blurred vision and halos or rainbows around lights as a result of corneal edema. These patients often have pronounced pain around the eye, as well as nausea and vomiting, and their condition may be misdiagnosed as a migraine.17,18 Examination findings during an acute episode of angle closure include a mid-dilated pupil, conjunctival injection, and a cloudy cornea; these are not typically present in a migraine. Patients with subacute angle closure may have milder or intermittent symptoms that may resolve upon entrance into a well-lit room or with sleep, both of which induce pupillary miosis.16 Identification of patients who are at risk of acute angle closure requires examination of the angle of the eye by an ophthalmologist.

As with POAG, most patients who have PACG were previously diagnosed with a chronic disease, are asymptomatic, and are unaware of any visual field loss. In addition to the therapies available for POAG, laser peripheral iridotomy or cataract extraction may be offered to patients with PACG to lower their risk of acute angle closure.

Certain medications that may cause pupillary dilation (e.g., antihistamines, asthma medications, tricyclic antidepressants, adrenergics, anticholinergics) can increase the chance that an at-risk patient will have an episode of acute angle closure.19 Sulfa derivatives and cholinergics may also lead to acute angle closure in at-risk persons.19 However, most patients with glaucoma in the United States have POAG, which is not significantly affected by occasional use of such medications.

Screening

Measurement of intraocular pressure alone is a poor method of detecting glaucoma. One-half of patients with POAG have an intraocular pressure within the normal range, and most patients with elevated pressure (22 mm Hg or greater) do not develop glaucoma.7,8,20 Further, intraocular pressure measurements vary diurnally.21 Screening that uses intraocular pressure or fundus photography alone has a sensitivity of less than 50% and specificity near 90%; accuracy varies by patient age, race, and family history of glaucoma.22 Newer methods that measure the thickness of the nerve fibers that comprise the optic nerve offer similarly poor sensitivity.23 Screening with visual field testing alone increases specificity and sensitivity, but requires special equipment typically not available in a primary care physician's office.24 Accurate diagnosis of glaucoma requires examination beyond what is routinely performed in the primary care setting, such as measurement of intraocular pressure, stereoscopic optic nerve examination, and formal visual field testing. Examinations are repeated over time to assess the optic nerve head for neuroretinal tissue loss and to screen for the development of visual field scotomas. Ophthalmoscopy by family physicians has been shown to have inadequate sensitivity or specificity in diabetic retinopathy.25,26 The same is likely true for optic nerve head examination, where accurate description of the optic nerve head requires stereopsis (i.e., binocularity), which cannot be obtained with a direct ophthalmoscope.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening for POAG in the primary care setting, citing insufficient evidence to assess the benefits or harms of screening. The American Academy of Family Physicians agrees with this position (https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/glaucoma.html). Specifically, there have been no randomized controlled trials comparing screened with unscreened populations.27 In the American Academy of Ophthalmology guideline, regular eye examinations are recommended for patients older than 40 years by an eye professional. The guideline further recommends that persons who have risk factors associated with glaucoma consider more frequent or earlier examinations, at the discretion of their optometrist or ophthalmologist.28 Screening low- or average-risk persons is not considered useful, according to expert consensus.29

Risk Factors for Glaucoma

Primary care physicians can identify patients with risk factors for glaucoma and refer these patients to an ophthalmologist for examination. Screening of high-risk groups increases the positive predictive value of screening tests and was shown to be cost-effective (specifically in black patients and persons with a family history of glaucoma).30 However, clinical trials assessing the outcomes of screening in high-risk groups are still needed. The USPSTF does not currently recommend screening asymptomatic adults for glaucoma.27 Known risk factors for glaucoma are listed in Table 131–43 and reviewed below.

| Risk factors* | RR, OR, or prevalence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of glaucoma31,32 | OR = 3.7 to 16.6 (siblings) | |||

| OR = 1.1 to 2.2 (child or parent) | ||||

| Age33,34 | OR = 1.6 to 2.2 per decade | |||

| Race and ethnicity35–40 | RR = 3.7 to 4.3 (blacks and POAG) | |||

| RR = 2.8 (Chinese ethnicity and PACG) | ||||

| OR = 3.6 (Chinese ethnicity and PACG) | ||||

| Prevalence by race and ethnicity (POAG)35–38 | ||||

| 40 to 49 years | Older than 80 years | Total | ||

| Blacks | 1.3% to 1.4% | 11.3% to 23.2% | 5.0% to 6.8% | |

| Hispanics | 0.5% to 1.3% | 12.6% to 21.8% | 2.0% to 4.7% | |

| Whites | 0.2% to 0.5% | 1.9% to 11.4% | 1.4% to 3.4% | |

| Diabetes mellitus41,42 | RR = 1.4 to 1.5 | |||

| Female sex39,40,43 | OR = 1.4 to 1.7 (for patients with PACG) | |||

| RR = 2.4 (for patients with PACG) | ||||

FAMILY HISTORY

Family history of glaucoma in a first-degree relative is associated with a significantly increased risk of glaucoma.31 For example, having a sibling with glaucoma has an odds ratio of 3.7 for POAG.32 However, specific genetic mutations associated with glaucoma account for less than 5% of all cases of POAG.44

ETHNIC ORIGIN

Blacks and Hispanics have an increased prevalence of POAG, more severe glaucoma on presentation, and a higher risk of blindness. PACG is proportionately more prevalent in persons with Inuit, Chinese, Asian Indian, or Southeast Asian background.1,35–37,45 The prevalence and risk of blindness from glaucoma are higher in developing countries.1,46

AGE

The prevalence of glaucoma increases sharply with age. The rate of glaucoma among blacks and Hispanics 40 to 49 years of age is approximately 1% in each population. In black and Hispanic persons older than 80 years, the prevalence of glaucoma ranges from 11.3% to 23.2% and 12.6% to 21.8%, respectively.35–38 In whites older than 75 years, the prevalence of POAG is 9%.47

OTHER RISK FACTORS

Population studies have reported conflicting results regarding the association between diabetes mellitus and glaucoma.48,49 However, recent meta-analyses have concluded that diabetes is associated with a greater risk of developing POAG (pooled relative risk = 1.40 to 1.48) and higher intraocular pressure.41,42

Recent studies have shown that nocturnal hypotension or dips in nocturnal blood pressure are associated with progression of visual field deficits in patients with glaucoma. However, the clinical implications are uncertain.50–52 Additional risk factors for glaucoma may be discovered during a detailed eye examination, including elevated intraocular pressure, thin central corneal thickness, and refractive error (myopia is risk factor for POAG, and hyperopia is a risk factor for PACG).53

Treatment

A previous review in American Family Physician provides a listing of the eye drops most commonly used to treat glaucoma and their typical dosing.11 As with management of systemic hypertension, control of intraocular pressure in glaucoma may require multiple drugs of different classes. Common adverse effects of topical agents used in glaucoma are listed in Table 2. Use of glaucoma medications delays visual field loss by lowering intraocular pressure and reduces the absolute risk of progression by 17% in patients with early glaucoma.8 The U.K. Glaucoma Treatment Study, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, published results in 2015 showing longer visual field preservation in patients with POAG taking latanoprost (Xalatan).54

| Medication class | Mechanism of action | Drug names | Dosing interval | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-adrenergic agonists | Decreases aqueous humor production | Apraclonidine (Iopidine), brimonidine (Alphagan) | Two to three times daily | Ocular allergy, somnolence, bitter taste, dry mouth, systemic hypotension, irregular heart rate |

| Beta blockers | Decreases aqueous humor production | Betaxolol (Betoptic), carteolol, levobunolol (Betagan), metipranolol (Optipranolol), timolol (Timoptic) |

|

|

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors | Decreases aqueous humor production | Brinzolamide (Azopt), dorzolamide (Trusopt) | Two times daily | Ocular irritation, sour taste |

| Cholinergics | Increases outflow through trabecular meshwork | Pilocarpine | Three to four times daily | Blurred vision, poor night vision, eye pain, headache |

| Prostaglandin analogues* | Increases outflow through uveoscleral pathway | Bimatoprost (Lumigan), latanoprost (Xalatan), tafluprost (Zioptan), travoprost (Travatan), unoprostone (Rescula) | One time daily, typically at bedtime | Lengthening of eyelashes, change in iris color or periocular skin hyperpigmentation, hyperemia, intraocular inflammation, and keratitis |

Surgery may be indicated in patients who continue to show progressive visual field loss on maximal medical therapy, are intolerant of glaucoma medications, or are poorly adherent to treatment plans. Glaucoma surgeries are outpatient procedures. Many can be performed safely with only topical or local anesthetic, although retrobulbar injection of anesthetic and general anesthesia also may be used. In PACG, laser iridotomy is often performed at initial diagnosis to reduce the risk of acute angle closure. Laser trabeculoplasty for POAG (or less commonly, PACG) is performed in a clinical setting and increases outflow through conventional aqueous outflow mechanisms. Laser treatment is similarly effective as topical medication and may be a good option for patients with poor medication adherence.55 The most common forms of incisional glaucoma surgery (trabeculectomy and tube shunt devices) are performed in an operating room and bypass the normal outflow of aqueous humor via the trabecular meshwork, instead shunting aqueous humor to the subconjunctival space. Patients who are being treated for glaucoma or have had glaucoma surgery should see their ophthalmologist as directed.

Prognosis

Even among patients who receive treatment, nearly one in seven persons with glaucoma will be blind in one eye within two decades.56,57 In one study, one out of six patients was bilaterally blind at the most recent ophthalmology visit.58 Important risk factors for disease progression and blindness include advanced disease at initial presentation and nonadherence with treatment and clinic visits.57,59,60 The mainstay of treatment for glaucoma is the use of topical eye drops. Therefore, primary care physicians should ask patients about use of eye drops and remind them at health maintenance visits to apply the drops as prescribed.

Data Sources: PubMed and Google Scholar searches were completed using the key terms glaucoma, screening, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, the Cochrane database, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: November 2014 and April 2015.