A more recent article on evaluation and management of dizziness is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(3):154-162

Related letter: Cerebrovascular Disease as a Cause of Dizziness

Patient information: See related handout on dizziness, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Dizziness is a common yet imprecise symptom. It was traditionally divided into four categories based on the patient's history: vertigo, presyncope, disequilibrium, and light-headedness. However, the distinction between these symptoms is of limited clinical usefulness. Patients have difficulty describing the quality of their symptoms but can more consistently identify the timing and triggers. Episodic vertigo triggered by head motion may be due to benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Vertigo with unilateral hearing loss suggests Meniere disease. Episodic vertigo not associated with any trigger may be a symptom of vestibular neuritis. Evaluation focuses on determining whether the etiology is peripheral or central. Peripheral etiologies are usually benign. Central etiologies often require urgent treatment. The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help distinguish peripheral from central etiologies. The physical examination includes orthostatic blood pressure measurement, a full cardiac and neurologic examination, assessment for nystagmus, and the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Laboratory testing and imaging are not required and are usually not helpful. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo can be treated with a canalith repositioning procedure (e.g., Epley maneuver). Treatment of Meniere disease includes salt restriction and diuretics. Symptoms of vestibular neuritis are relieved with vestibular suppressant medications and vestibular rehabilitation.

Dizziness is a common yet imprecise symptom often encountered by family physicians. Primary care physicians see at least one-half of the patients who present with dizziness.1 The differential diagnosis is broad, with each of the common etiologies accounting for no more than 10% of cases2 (Table 11,3 ). Because the symptoms are vague, physicians must distinguish benign from serious causes that require urgent evaluation and treatment.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: EVALUATION OF DIZZINESS

TiTrATE is a novel diagnostic approach to determine the probable etiology of dizziness or vertigo. It uses the Timing of the symptom, the Triggers that provoke the symptom, And a Targeted Examination. The patient's response determines the classification of dizziness as episodic triggered, spontaneous episodic, or continuous vestibular.

In a study of older patients in a primary care setting, medications were implicated in 23% of cases of dizziness.

The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help differentiate a peripheral cause of vestibular neuritis from a central cause.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Vertigo associated with unilateral hearing loss should raise suspicion for Meniere disease. | C | 41 |

| The physical examination in patients with dizziness should include orthostatic blood pressure measurement, nystagmus assessment, and the Dix-Hallpike maneuver for triggered vertigo. | C | 16 |

| The HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help differentiate a peripheral cause of vestibular neuritis from a central cause. | C | 20 |

| Laboratory testing and imaging are not recommended when no neurologic abnormality is found on examination. | C | 1 |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is treated with a canalith repositioning procedure (e.g., Epley maneuver). | A | 30 |

| Vestibular neuritis symptoms may be relieved with medication and vestibular rehabilitation. | C | 20 |

| Meniere disease may improve with a low-salt diet and diuretic use. | B | 41 |

| Cause (most to least frequent) | Clinical description |

|---|---|

| Peripheral causes | |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | Transient triggered episodes of vertigo caused by dislodged canaliths in the semicircular canals |

| Vestibular neuritis | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo caused by inflammation of the vestibular nerve or labyrinthine organs, usually from a viral infection |

| Meniere disease | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo associated with unilateral hearing loss caused by excess endolymphatic fluid pressure in the inner ear |

| Otosclerosis | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo caused by abnormal bone growth in the middle ear and associated with conductive hearing loss |

| Central causes | |

| Vestibular migraine | Spontaneous episodes of vertigo associated with migraine headaches |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Continuous spontaneous episodes of vertigo caused by arterial occlusion or insufficiency, especially affecting the vertebrobasilar system |

| Cerebellopontine angle and posterior fossa meningiomas | Continuous spontaneous episodes of dizziness caused by vestibular schwannoma (i.e., acoustic neuroma), infratentorial ependymoma, brainstem glioma, medulloblastoma, or neurofibromatosis |

| Other causes | |

| Psychiatric | Initially episodic, then often continuous episodes of dizziness without another cause and associated with psychiatric condition (e.g., anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder) |

| Medication induced | Continuous episodes of dizziness without another cause and associated with a possible medication adverse effect |

| Cardiovascular/metabolic | Acute episodic symptoms that are not associated with any triggers |

| Orthostatic | Acute episodic symptoms associated with a change in position from supine or sitting to standing |

Dizziness was traditionally classified into four categories based on the patient's description: (1) vertigo, (2) presyncope, (3) disequilibrium, and (4) light-headedness.4 However, current approaches do not include presyncope and do not use the vague term light-headedness.5 Patients often have difficulty describing their symptoms and may give conflicting accounts at different times.3 Symptom quality does not reliably predict the cause of dizziness.6 Physicians are cautioned against overreliance on a descriptive approach to guide the diagnostic evaluation.7 Alternatively, attention to the timing and triggers of dizziness is preferred over the symptom type because patients more consistently report this information.3,7

General Approach

Questions regarding the timing (onset, duration, and evolution of dizziness) and triggers (actions, movements, or situations) that provoke dizziness can categorize the dizziness as more likely to be peripheral or central in etiology. Findings from the physical examination can help confirm a probable diagnosis. A diagnostic algorithm can help determine whether the etiology is peripheral or central (Figure 1).

TITRATE THE EVALUATION

TiTrATE is a novel diagnostic approach to determining the probable etiology of dizziness or vertigo.2 The approach uses the Timing of the symptom, the Triggers that provoke the symptom, And a Targeted Examination. The responses place the dizziness into one of three clinical scenarios: episodic triggered, spontaneous episodic, or continuous vestibular.

With episodic triggered symptoms, patients have brief episodes of intermittent dizziness lasting seconds to hours. Common triggers are head motion on change of body position (e.g., rolling over in bed). Episodic triggered symptoms are consistent with a diagnosis of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

With spontaneous episodic symptoms (no trigger), patients have episodes of dizziness lasting seconds to days. Because these episodes have no trigger, the patient's history establishes the diagnosis. Common diagnostic considerations for spontaneous episodic symptoms include Meniere disease, vestibular migraine, and psychiatric diagnoses such as anxiety disorders. Symptoms associated with lying down are more likely vestibular.

With continuous vestibular symptoms, patients have persistent dizziness lasting days to weeks. The symptoms may be due to traumatic or toxic exposure. Classic vestibular symptoms include continuous dizziness or vertigo associated with nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, gait instability, and head-motion intolerance. In the absence of trauma or exposures, these findings are most consistent with vestibular neuritis or central etiologies. However, central causes can also occur with patterns triggered by movement.

HISTORY: TIMING, TRIGGERS, AND MEDICATIONS

Patients who describe a sensation of self-motion when they are not moving or a sensation of distorted self-motion during normal head movement may have vertigo.5 Vertigo is the result of asymmetry within the vestibular system or a disorder of the peripheral labyrinth or its central connections.8,9 The distinction between vertigo and dizziness is of limited clinical usefulness.2

If vertigo is described, physicians should ask about hearing loss, which could suggest Meniere disease.10 Diagnostic criteria for Meniere disease include episodic vertigo (at least two episodes lasting at least 20 minutes) associated with documented low- to medium-frequency sensorineural hearing loss by audiometric testing in the affected ear and tinnitus or aural fullness in the affected ear.10 The auditory symptoms are initially unilateral.

Physicians should determine whether the vertigo is triggered by a specific position or change in position. BPPV is triggered with sudden changes in position, such as a quick turn of the head on awakening or tipping the head back in the shower. Dizziness from orthostatic hypotension occurs with movement to the upright position. Clinicians may erroneously assume that dizziness that worsens with movement is associated with a benign condition in patients with persistent dizziness.11 However, exacerbation of symptoms with movement is common to most causes of persistent dizziness and does not aid in determining whether the etiology is peripheral vs. central (benign vs. dangerous).7

Medications were implicated in 23% of cases of dizziness in older adults in a primary care setting12 (Table 21,13,14 ). The use of five or more medications is associated with an increased risk of dizziness.15 Older patients are particularly susceptible to medication adverse effects because of age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes.13

| Medication | Causal mechanism |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Findings from the physical examination—including a cardiac and neurologic assessment, with attention to the head, eye, ear, nose, and throat examination—are usually normal in patients presenting with dizziness.

Blood pressure should be measured while the patient is standing and in the supine position.16 Orthostatic hypotension is present when the systolic blood pressure decreases 20 mm Hg, the diastolic blood pressure decreases 10 mm Hg, or the pulse increases 30 beats per minute after going from supine to standing for one minute.17 A full neurologic examination should be performed in patients with orthostatic dizziness but no hypotension or BPPV.

The patient's gait should be observed and a Romberg test performed. Patients with an unsteady gait should be assessed for peripheral neuropathy.18 A positive Romberg test suggests an abnormality with proprioception receptors or their pathway.

The use of the HINTS (head-impulse, nystagmus, test of skew) examination can help distinguish a possible stroke (central cause) from acute vestibular syndrome (peripheral cause).19 A video demonstrating this examination is available at http://www.kaltura.com/index.php/extwidget/preview/partner_id/797802/uiconf_id/27472092/entry_id/0_b9t6s0wh/embed/auto.

Head-Impulse. While the patient is sitting, the head is thrust 10 degrees to the right and then to the left while the patient's eyes remain fixed on the examiner's nose. If a saccade (rapid movement of both eyes) occurs, the etiology is likely peripheral.20 No eye movement strongly suggests a central etiology.19

Nystagmus. The patient should follow the examiner's finger as it moves slowly left to right. Spontaneous unidirectional horizontal nystagmus that worsens when gazing in the direction of the nystagmus suggests a peripheral cause (vestibular neuritis).7 Spontaneous nystagmus that is dominantly vertical or torsional, or that changes direction with the gaze (gaze-evoked bidirectional) suggests a central etiology. Central pathology nystagmus changes direction less than half the time6 and can be suppressed with fixation.21 A video-oculography device is available to quantitatively measure eye movement.22 Frenzel goggles used to detect involuntary eye movements have been helpful with nystagmus assessment.23

Test of Skew. Test of skew is assessed by asking the patient to look straight ahead, then cover and uncover each eye. Vertical deviation of the covered eye after uncovering is an abnormal result. Although this is a less sensitive test for central pathology, an abnormal result is fairly specific for brainstem involvement.

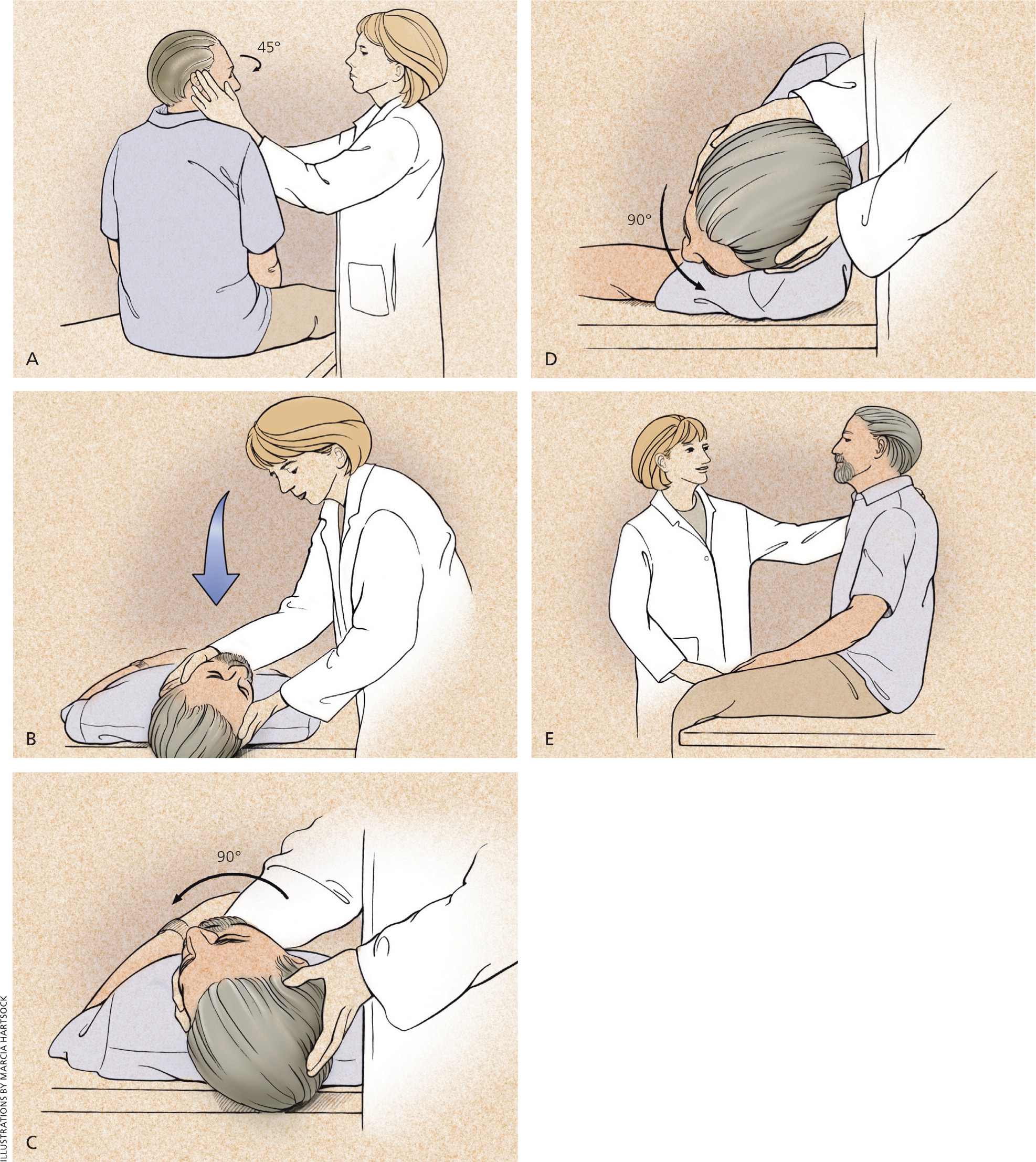

BPPV is diagnosed with the Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Figure 2).24 Transient upbeat-torsional nystagmus during the maneuver is diagnostic of BPPV if the timing and trigger are consistent with BPPV. Nystagmus may not develop immediately, and a sense of vertigo may occur and last for one minute. A negative result does not rule out BPPV if the timing and triggers are consistent with BPPV.25 Nystagmus with the maneuver may be due to a central etiology, especially if the timing and trigger are not consistent with BPPV.

LABORATORY TESTING AND IMAGING

Most patients presenting with dizziness do not require laboratory testing. Patients with chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension) may require blood glucose and electrolyte measurements. Patients with symptoms suggestive of cardiac disease should undergo electrocardiography, Holter monitoring, and possibly carotid Doppler testing. However, in a summary analysis of multiple studies that included 4,538 patients, only 26 (0.6%) had a laboratory result that explained their dizziness.16

Routine imaging is not indicated.1 However, any abnormal neurologic finding, including asymmetric or unilateral hearing loss, requires computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate for cerebrovascular disease. Hearing loss with vertigo and normal neuroimaging suggests Meniere disease.

Peripheral Etiologies

Peripheral causes of dizziness arise from abnormalities in the peripheral vestibular system, which is comprised of the semicircular canals, the saccule, the utricle, and the vestibular nerve. Common peripheral causes of dizziness/vertigo include BPPV, vestibular neuritis (i.e., vestibular neuronitis), and Meniere disease.26

BENIGN PAROXYSMAL POSITIONAL VERTIGO

BPPV occurs when loose otoconia, known as canaliths, become dislodged and enter the semicircular canals, usually the posterior canal.27 BPPV can occur at any age, but is most common between 50 and 70 years.28 No obvious cause is found in 50% to 70% of older patients, but head trauma is a possibility in younger persons.29

Treatment of BPPV consists of a canalith repositioning procedure such as the Epley maneuver, which repositions the canalith from the semicircular canal into the vestibule30 (Figure 324 ). The success rate is approximately 70% on the first attempt, and nearly 100% on successive maneuvers.29 Home treatment with Brandt-Daroff exercises (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=voZXtTUdQ00) can also be successful. If there is no improvement with repeated repositioning maneuvers, or if atypical or ongoing nystagmus with nausea is present, another cause should be considered.27

VESTIBULAR NEURITIS

Vestibular neuritis, the second most common cause of vertigo, is thought to be of viral origin. It most commonly affects persons 30 to 50 years of age. Men and women are affected equally.

Vestibular neuritis is diagnosed on the basis of the clinical history and physical examination.32 It can cause severe rotatory vertigo with nausea and apparent movement of objects in the visual field (oscillopsia), horizontally rotating spontaneous nystagmus to the nonaffected side, or an abnormal gait with a tendency to fall to the affected side. Hearing is not impaired in this condition. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is not useful because patients with vestibular neuritis do not have episodic positionally triggered symptoms.

As vestibular compensation occurs, the patient's vertigo resolves slowly over a few days.33 In 50% of patients, the underlying nerve damage may take two months to resolve.34 However, a sensation of disequilibrium may persist for months because of unilateral impairment of vestibular function. Vertigo may recur, indicating interference with compensation. If the attacks do not become successively shorter, another diagnosis should be considered.

Vestibular neuritis is treated with medications and vestibular rehabilitation20 (Table 320,24 ). Antiemetics and antinausea medications should be used for no more than three days because of their effects in blocking central compensation. Vertigo and associated nausea or vomiting can be treated with a combination of antihistamine, antiemetic, or benzodiazepine. Although systemic corticosteroids have been recommended as a treatment for vestibular neuritis, there is insufficient evidence for their routine use.36 Antiviral medications are ineffective.37

| Medication | Dosage | Adverse effects | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiemetics | |||

| Metoclopramide (Reglan) | 5 to 10 mg orally every 6 hours, or 5 to 10 mg slowly IV every 6 hours | Akathesia, atrioventricular block, bradycardia, bronchospasm, dizziness, drowsiness, dystonic reaction, gynecomastia, nausea, tardive dyskinesia | Tablets: $2 ($25) |

| Prochlorperazine | 5 to 10 mg orally or IM every 6 to 8 hours | Agitation, dizziness, drowsiness, dystonic reaction, extrapyramidal symptoms, photosensitivity, tardive dyskinesia | Tablets: $2 |

| Antihistamines | |||

| Dimenhydrinate | 50 mg orally every 6 hours | Anorexia, blurred vision, dizziness, drowsiness, nausea | $3 |

| Meclizine (Antivert) | 12.5 to 50 mg orally every 4 to 8 hours | Blurred vision, drowsiness, fatigue, headache, vomiting | $1 to $4 ($8 to $47) |

| Promethazine | 25 mg every 6 hours orally, IM, or rectally every 4 to 12 hours | Agitation, bradycardia, confusion, constipation, drowsiness, dizziness, dystonia, extrapyramidal symptoms, gynecomastia, photosensitivity, urinary retention | Tablets: $2 Suppository: $3 |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Diazepam (Valium) | 2 to 10 mg orally or IV every 4 to 8 hours | Amnesia, drowsiness, slurred speech, vertigo | Tablets: $1 ($30 to $168) |

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | 1 to 2 mg orally every 4 hours | Amnesia, dizziness, drowsiness, slurred speech, vertigo | $1 ($320 to $500) |

MENIERE DISEASE

Meniere disease causes vertigo and unilateral hearing loss. Although it can develop at any age, it is more common between 20 and 60 years.38 The vertigo associated with Meniere disease is often severe enough to necessitate bed rest and can cause nausea, vomiting, and loss of balance. Other symptoms include sudden slips or falls, and headache with hearing loss worsened during an attack.39

The underlying pathology is excess endolymphatic fluid pressure leading to inner ear dysfunction; however, the exact cause is unknown.40 Patients manifest a unidirectional, horizontal-torsional nystagmus during vertigo episodes.

First-line treatment of Meniere disease involves lifestyle changes, including limiting dietary salt intake to less than 2,000 mg per day, reducing caffeine intake, and limiting alcohol to one drink per day. Daily thiazide diuretic therapy can be added if vertigo is not controlled with lifestyle changes.41

Vestibular suppressant medications may be used for acute attacks.20 Prochlorperazine, promethazine, and diazepam (Valium) have been effective. Surgery is an option for patients with refractory symptoms.41 Vestibular exercises may be helpful for patients with unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction.44 Vestibular rehabilitation may be needed for persistent tinnitus or hearing loss.

Central Etiologies

The vestibular nuclei, cerebellum, brainstem, spinal cord, and vestibular cortex make up the central vestibular system. Central abnormalities cause approximately 25% of dizziness experienced by patients.45 Common central etiologies include vestibular migraine and vertebrobasilar ischemia. Patients with central pathology may present with disequilibrium and ataxia rather than true vertigo. However, vertigo can be a presenting symptom of an impending cerebrovascular event.46,47

Potentially deadly central causes of acute vestibular syndrome may mimic a more benign peripheral disorder, and a stroke may present with no focal neurologic signs. Computed tomography does not have adequate sensitivity to distinguish stroke from benign causes of acute vestibular syndrome. The HINTS examination is highly sensitive and specific in identifying stroke in patients with acute vestibular syndrome, and it is superior to diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in ruling out stroke.6

VESTIBULAR MIGRAINE

Episodic vertigo in a patient with a history of migraine headaches suggests vestibular migraine.48 Vestibular migraine is one of the most common causes of episodic vertigo among children.49 Among adults, it is three times more common among women and more often occurs between 20 and 50 years of age.50 A family history of vestibular migraine is a risk factor.

The diagnostic criteria for vestibular migraine include at least five episodes of vestibular symptoms of moderate or severe intensity lasting five minutes to 72 hours; current or previous history of migraine headache; one or more migraine features, and at least 50% with vestibular symptoms; and no other cause of vestibular symptoms.51

Initial management focuses on identifying and avoiding migraine triggers. Stress relief is recommended, and adequate sleep and exercise are encouraged. Vestibular suppressant medications are helpful.20 Because of a lack of well-designed randomized clinical trials, prevention recommendations are based on expert opinion.52 Preventive medications include anticonvulsants, beta adrenergic blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, butterbur extract, and magnesium. The goal is a 50% reduction in attacks.20 It is not clear whether migraine abortive therapy is effective in treating vertigo.20

VERTEBROBASILAR ISCHEMIA

The blood supply to the brainstem, cerebellum, and inner ear is derived from the vertebrobasilar system. Any major branch occlusion can cause vertigo. Diagnosis usually relies on a history of brainstem symptoms, such as diplopia, dysarthria, weakness, or clumsiness of the limbs. Vertigo is the initial symptom in 48% of patients, although fewer than one-half will have an associated neurologic finding.53 Treatment includes antiplatelet therapy and reduction of risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. Warfarin (Coumadin) has been used in cases of significant vertebral or basilar artery stenosis.54

Data Sources: A PubMed and Ovid search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key words dizziness, vertigo, disequilibrium, and presyncope. Additional search terms included Meniere disease, Epley maneuver, and vestibular neuritis. The Cochrane Library and Essential Evidence Plus were searched using the key words vertigo and dizziness. Last search date: October 2015.