A more recent article on HIV-associated complications is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(3):161-169

Patient information: See related handout on common side effects of HIV medicine, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection often develop complications related directly to the infection, as well as to treatment. Aging, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities increase the risk of developing chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. HIV-associated neurologic complications encompass a wide spectrum of pathophysiology and symptomatology. Cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions are common among persons with HIV infection. Although some specific antiretroviral medications have been linked to disease development, traditional risk factors (e.g., smoking) have major roles. Prevention and management of viral hepatitis coinfection are important to reduce morbidity and mortality, and new anti–hepatitis C agents produce high rates of sustained virologic response. Antiretroviral-associated metabolic complications include dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and loss of bone mineral density. Newer options generally pose less risk of significant systemic toxicity and are better tolerated. Family physicians who care for patients with HIV infection have a key role in identifying and managing many of these chronic complications.

Current U.S. treatment guidelines support antiretroviral therapy (ART) for all patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.1 However, most HIV-associated complications arise directly from chronic infection that results in immunologic impairment and inflammation, and indirectly through aging, ART, and lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients should be evaluated for potential interactions between antiretrovirals and concurrent medications (including over-the-counter agents). | C | 1 |

| Patients should be screened for kidney disease when HIV infection is diagnosed, then twice yearly in stable patients, and more frequently in high-risk patients. | C | 1, 15, 50 |

| Cervical cancer screening in women with HIV infection should begin within one year of the onset of sexual activity regardless of the mode of HIV transmission, but no later than 21 years of age. (See Table 4 for specific screening recommendations.) | C | 53 |

| Patients should be screened for lipid and glucose disorders when HIV infection is diagnosed, then monitored regularly. | C | 1, 15 |

| Clinicians should consider switching antiretroviral combinations to more lipid- and/or glucose-neutral regimens if specific agents are suspected of causing or worsening significant hyperlipidemia or hyperglycemia. | C | 1, 55 |

| Baseline bone mineral density should be measured in postmenopausal women, men 50 years and older, and other patients at high risk of osteoporotic fracture. | C | 58 |

This article updates a previous review 2 of key HIV- and ART-related complications; opportunistic infections and other AIDS-defining conditions are not discussed. Major neurologic, cardiopulmonary, hepatic, renal, and metabolic complications of HIV infection are emphasized because of their prevalence and contributions to morbidity and mortality.3–6 Except where noted, complications can occur at any CD4 count. Although opportunistic infections have decreased with widespread use of chemoprophylaxis and ART,7,8 clinicians should remain vigilant in patients with low CD4 counts (i.e., less than 200 cells per mm3 [0.20 × 109 per L]). Table 1 provides a list of clinical and educational resources on HIV.

| AIDSinfo | |

| 800-448-0440 | |

| https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines | |

| Johns Hopkins University Point of Care-Information Technology HIV Guide | |

| http://www.hopkinsguides.com/hopkins/ub | |

| New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute/Johns Hopkins University HIV Clinical Resource | |

| http://www.hivguidelines.org | |

| University of California, San Francisco, Clinician Consultation Center | |

| 800-933-3413 | |

| http://nccc.ucsf.edu | |

| University of California, San Francisco, HIV InSite | |

| http://www.hivinsite.org | |

| University of Liverpool HIV drug interactions website | |

| http://www.hiv-druginteractions.org/ | |

| University of Washington HIV web study website | |

| http://www.hivwebstudy.org | |

Neurologic Complications

| Complication | Notes |

|---|---|

| Neurologic* | |

| Myelopathy (i.e., vacuolar myelopathy) | Common cause of spinal cord dysfunction, especially in advanced HIV infection; symptoms include gait difficulty, increased lower extremity tone, progressive lower extremity weakness/sensory impairment, and sphincter/erectile dysfunction |

| Myopathy (i.e., HIV-associated polymyositis) | Similar presentation as autoimmune polymyositis: gradual, progressive, symmetric proximal weakness |

| Other peripheral sensory neuropathies | Examples include inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, and progressive polyradiculopathy; often associated with opportunistic pathogens (e.g., cytomegalovirus) in advanced HIV infection |

| Primary headache disorders | Common in persons with HIV infection (6% to 61%)10–13; etiology often mixed/unclear |

| Space-occupying CNS lesions and CNS-targeting infections | Differential diagnosis guided by CD4 count and may include primary CNS lymphoma, syphilis, and opportunistic infections (e.g., Toxoplasma, Cryptococcus, cytomegalovirus, JC polyomavirus) |

| Cardiovascular and pulmonary† | |

| Cardiomyopathy, endocarditis, myocarditis, and pericarditis | Relatively rare; may be associated with opportunistic pathogens in advanced HIV infection |

| HIV-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension | Rare (0.5% incidence), although rates have not decreased with widespread use of ART 14; exact etiology and relationship between prognosis and ART are uncertain |

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | Rates have dramatically decreased; occurs primarily in persons with CD4 counts ≤ 200 cells per mm3 (0.20 × 109 per L) who are unaware of HIV status or not in care |

| Tuberculosis | ART greatly reduces risk; all patients with HIV infection should be screened at time of HIV diagnosis, then annually if at risk15 |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatic‡ | |

| AIDS cholangiopathy, infiltrative hepatobiliary and pancreatic infections | Often caused by opportunistic pathogens; should be managed promptly when identified (some conditions can be fatal if untreated) |

| Infectious colitis, esophagitis, and gastroenteritis | More common in patients with significant immunosuppression; infectious agents cause variably located lesions throughout gastrointestinal tract; if stool studies are nondiagnostic, endoscopy with biopsy and directed histopathology can help identify causative agents16 |

| Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency | Leads to fat malabsorption and bowel movement changes, bloating, and weight loss |

| Renal | |

| Acute kidney injury | Most commonly attributed to prerenal conditions and acute tubular necrosis; may also be due to HIV-related medications (Table 3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | Risk factors include hepatitis C virus coinfection, high HIV viral load, low CD4 count, and traditional risk factors (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension); HIV-associated nephropathy typically presents as significant proteinuria and rapid decline in kidney function (blood pressure often normal); biopsy required for definitive diagnosis |

| Metabolic and endocrine§ | |

| Disorders of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and gonadal axes | Can be due to central or peripheral etiology (including opportunistic infections); HIV infection can directly lead to adrenal insufficiency |

| Dermatologic | |

| Alopecia | May be due to chronic HIV infection, immune or endocrine dysregulation, local or systemic infections, medications, or nutritional deficiencies |

| Infectious dermatoses | May be bacterial, fungal, or viral (e.g., Kaposi sarcoma associated with human herpes virus 8) |

| Noninfectious dermatoses | Examples include atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, eosinophilic folliculitis, prurigo nodularis (especially in patients with hepatitis C virus coinfection), psoriasis (severe skin disease can occur in patients with low CD4 counts), and xerosis |

| Hematologic | |

| Anemia | Usually multifactorial; exclude opportunistic processes in patients with advanced HIV infection |

| HIV-associated thrombocytopenia | May present at any time, although risk increases with progressive immunosuppression |

| Malignancy | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is most common |

| Musculoskeletal and rheumatologic | |

| Myalgias/myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and asymptomatic creatine kinase elevation | May be due to HIV itself as well as some antiretrovirals (Table 3) |

| Osteonecrosis (i.e., avascular necrosis) | More common with chronic HIV infection or advanced disease |

| Various arthropathies | Multiple conditions have been described, including HIV-associated arthritis, gout, Reiter syndrome, and septic arthritis |

HIV-ASSOCIATED NEUROCOGNITIVE DISORDER

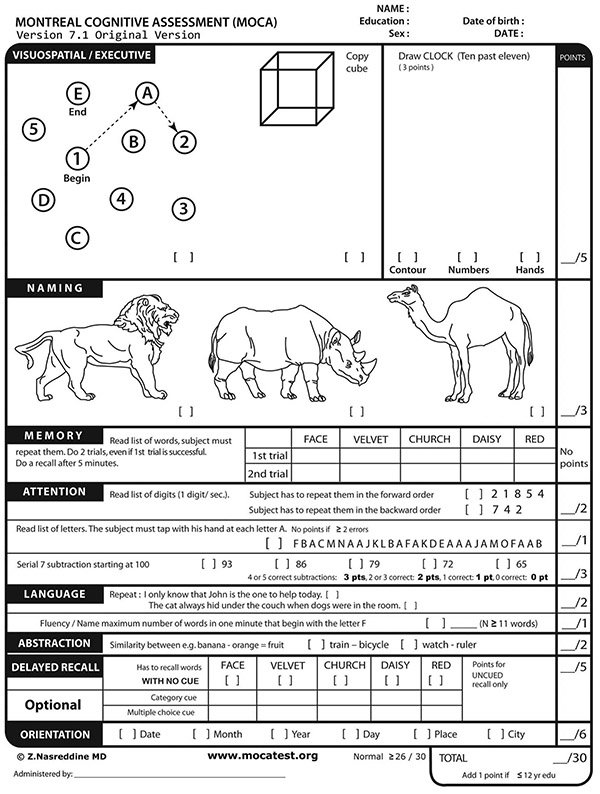

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder represents a wide spectrum of symptoms and may lead to poor ART adherence and decreased quality of life and/or functioning. The most severe form, HIV-associated dementia, generally occurs at low CD4 counts. Changes occur across three subcortical domains: cognitive (manifesting as memory, concentration, comprehension, or executive planning deficits); behavioral/affective (leading to apathy, depression, or agitation); and motor (gait unsteadiness, decreased coordination, tremor). Although routine screening is not recommended in asymptomatic patients, various tools can be used for initial assessment of those with deficits. No single tool has been proven superior, especially among patients with mild impairment. However, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment is a readily available instrument that can be useful as a first step18 (eFigure A).

Diagnosis remains challenging, and other disorders such as central nervous system infections/tumors, systemic causes, psychiatric conditions, and substance use should be excluded. Formal neuropsychologic testing may help in certain situations, such as when targeted cognitive rehabilitation is needed or when differentiating between HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder and psychiatric conditions. ART is the mainstay of treatment for these disorders.19

HIV-ASSOCIATED NEUROPATHY

Distal sensory polyneuropathy is the most common HIV-associated neuropathy and can be caused by HIV itself, as well as older antiretroviral medications20,21 (Table 31,22–26 ). Diagnosis is primarily clinical: signs and symptoms include reduced ankle reflexes and lower-extremity sensation (particularly to vibration and pinprick), numbness, paresthesia, and pain. Nerve conduction studies, electromyography, and skin/nerve biopsies are typically unnecessary but may help confirm the diagnosis and assess its severity. Management includes removing neurotoxins (e.g., didanosine, an older ART agent) and initiating symptom-directed measures; anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and topical analgesics have varying degrees of success.27–30 Factors that may complicate distal sensory neuropathy or treatment response (e.g., diabetes mellitus, alcohol use) should be addressed, and HIV virologic control is recommended to prevent progression.

| Complication/toxicity | Associated medication/notes |

|---|---|

| Integrase strand transfer inhibitors | |

| Asymptomatic elevations in creatine kinase levels, overt myopathy (rare) | Raltegravir22 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction | Class-wide potential; may be accompanied by elevated liver transaminase levels |

| Insomnia | Class-wide potential |

| Major drug interactions | Use caution with some over-the-counter antacids and other polyvalent cation–containing products; limit metformin to 1,000 mg per day in patients receiving dolutegravir |

| NNRTI–associated complications | |

| Hepatotoxicity | Nevirapine should not be initiated in women with CD4 counts > 250 cells per mm3 (0.25 × 109 per L) or in men with CD4 counts > 400 cells per mm3 (0.40 × 109 per L) |

| Hypersensitivity reaction | Class-wide potential |

| Impaired concentration, insomnia, vivid dreams, mood changes, dizziness | Efavirenz, rilpivirine |

| Major drug interactions | Coadministration of efavirenz with most statins typically results in decreased statin concentrations; use caution with concurrent use of some NNRTIs and certain anticonvulsants, antifungals, antimycobacterials, anxiolytics, dexamethasone, some hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral agents, methadone, and St. John's wort; rilpivirine interacts with histamine H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors |

| Metabolic changes | Efavirenz linked to dyslipidemia and BMD loss |

| Nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor–associated complications | |

| Acute kidney injury | Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (rare Fanconi syndrome) |

| Bone marrow suppression | Zidovudine |

| Cardiotoxicity | Association with abacavir is controversial; findings have been inconsistent23 |

| Hepatitis flare-up | Emtricitabine, lamivudine, and tenofovir are also active against HBV; monitor for hepatitis flare-up in patients with HBV coinfection if any of these agents are discontinued |

| Lactic acidosis, mitochondrial toxicity | Class-wide potential, especially with older agents (i.e., didanosine, stavudine, zidovudine); mitochondrial toxicity manifests in various ways, including sensory neuropathy and toxic myopathy |

| Metabolic complications | Body morphology changes, BMD loss, insulin resistance (especially with older agents); serum lipid changes may occur with or without concurrent body morphology changes |

| Nail discoloration | Emtricitabine, zidovudine |

| Pancreatitis | Didanosine, stavudine |

| Steatosis | Didanosine, stavudine, zidovudine |

| PI–associated complications | |

| Gastrointestinal adverse effects | Class-wide potential; typically manifests as gastric discomfort and bloating, loose stools, and nausea |

| Hepatotoxicity | Class-wide potential |

| Hyperbilirubinemia, cholelithiasis, nephrolithiasis | Atazanavir; nephrolithiasis also linked to indinavir, which is no longer commonly used |

| Hyperuricemia | Possible association with some boosted PIs24–26 |

| Metabolic changes | Boosted PIs have been linked to BMD loss, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance |

| Major drug interactions | Most PIs increase statin concentrations, increasing the risk of statin toxicity; use caution with concurrent use of PIs and some antiarrhythmics (including amiodarone), anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antifungals, antimycobacterials, antiplatelet agents, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, calcium channel blockers, hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral agents, methadone, most corticosteroids, phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, and St. John's wort; atazanavir interacts with H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors |

| Complications associated with other medications | |

| Bone marrow suppression | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (commonly used anti-Pneumocystis agent) |

| Interstitial nephritis | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| Pancreatitis | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

Vascular and Pulmonary Complications

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK

Studies show higher rates of myocardial infarction and atherosclerosis in persons with HIV infection,31 as well as higher than average rates of risk factors such as smoking and hypertension.32 Increased cardiovascular risk persists even with current HIV treatments, although in some cohorts the gap in the risk of myocardial infarction between persons with HIV infection and uninfected individuals has been closing.33 Observational studies have shown an association between myocardial infarction and a lower nadir CD4 count, suggesting that earlier ART may decrease subsequent cardiovascular risk.34 HIV treatment guidelines suggest caution or avoidance of abacavir and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) in persons with increased cardiac risk.1,23,35 Current recommendations for risk assessment and treatment of dyslipidemia in persons with HIV infection are based on 2013 guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association.36 Traditional risk factors should be identified and modified when possible.37

VASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

Several mechanisms increase the risk of cerebrovascular disease among older patients with HIV infection: direct HIV neurotoxicity, infections causing cerebral infarction, coagulopathies, and chronic inflammation leading to vasculopathies and thromboembolism. Persons with HIV infection have higher than average rates of traditional cerebrovascular risk factors such as smoking and injection drug use, coronary/carotid artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease.38 Additionally, HIV may exacerbate the negative effects of these risks. Persons with HIV infection have strokes at younger ages, and lower CD4 counts and higher viral load may increase this risk.39–41 ART-mediated metabolic changes may indirectly influence risk, although no specific medication has been consistently implicated in the development of cerebrovascular disease.

PULMONARY DISORDERS

Noninfectious pulmonary diseases, primarily chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and pulmonary arterial hypertension, cause morbidity and mortality in persons with HIV infection.42 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer are more common in this population than in the general population, largely because of the higher prevalence of non–HIV-specific risk factors, such as smoking.43,44 Smoking cessation is the most important intervention to reduce chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk in persons with HIV infection.45 Although opportunistic lung infections have declined significantly, bacterial pneumonia remains prevalent (eFigure B). Vaccination against pneumococcal disease and influenza can prevent complications of these infections.15

Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Complications

GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT DISORDERS

Gastrointestinal opportunistic infections have decreased with improved HIV treatment. For some patients, noninfectious processes such as aphthous ulcers, idiopathic HIV enteropathy, and malignancy should be considered. Additionally, many patients with HIV infection take medications that interact with commonly used antiretrovirals (e.g., over-the-counter antacids, proton pump inhibitors, histamine H2 receptor antagonists), and careful medication review is necessary.1 Sexually transmitted infections should be considered in patients with anorectal symptoms and a history of receptive anal intercourse. Human papillomavirus infection is associated with anal cancer.

HEPATIC DISORDERS

Liver disease is an increasing cause of morbidity and mortality among persons with HIV infection.3,46,47 Clinicians should be familiar with signs of viral hepatitis and alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. HIV can directly infect hepatic cells and cause chronic liver inflammation, as well as accelerate viral hepatitis progression. Direct-acting antivirals for treatment of hepatitis C virus have rates of more than 90% sustained virologic response in patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus.48 All coinfected patients should be evaluated and strongly considered for treatment, and clinicians should be aware of drug-drug interactions between medications for HIV and hepatitis C.

For patients who cannot receive hepatitis C treatment, ART should be initiated early and/or maintained to suppress HIV viremia and slow the development or progression of fibrosis. Patients should be screened and treated for alcohol use, obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes because these conditions can affect the liver. There are no approved pharmacologic interventions specifically for HIV-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; management primarily involves lifestyle and risk factor modification.49 At-risk patients should be offered hepatitis A and B vaccination.15

ART-ASSOCIATED COMPLICATIONS

Nausea, dyspepsia, and diarrhea are common adverse effects of ART, especially protease inhibitors. If poor tolerability results in decreased treatment adherence, alternate antiretrovirals may need to be considered. ART can affect the hepatobiliary system through several mechanisms: direct drug toxicity and/or drug metabolism, hypersensitivity reactions, mitochondrial toxicity, and immune reconstitution-mediated inflammation.46 Although transaminase elevation is a common complication of ART, recently approved agents generally have safer hepatic profiles.1 Nevertheless, many chronically infected patients were exposed to older agents, causing liver injury. Patients with HIV and hepatitis B virus coinfection should be monitored closely for hepatitis flare-ups when discontinuing nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors that are also active against hepatitis B virus.

Genitourinary Complications

RENAL DISEASE

Decreased renal function and proteinuria are associated with increased mortality in persons with HIV infection. Black race, older age, CD4 count less than 200 cells per mm3, HIV viremia, hepatitis C virus coinfection, and injection drug use are associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease.50 Early identification informs appropriate ART selection and dosing, as well as the need for further evaluation. Multiple consensus guidelines recommend that all patients be screened for renal disease at the time of HIV diagnosis, followed by twice-yearly monitoring in stable patients and more frequent monitoring in high-risk patients.1,15,50 HIV-associated nephropathy predominantly affects black patients and is more common with advanced immunosuppression. An angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor blocker is indicated in patients with clinically significant albuminuria or confirmed or suspected HIV-associated nephropathy; ART is also recommended for all patients with this condition.

ART-ASSOCIATED COMPLICATIONS

More than any other commonly used antiretroviral, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is associated with proximal tubule dysfunction, proteinuria, and decreased renal function. Clinicians should avoid starting TDF in patients with a glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2, and discontinue it if the glomerular filtration rate decreases more than 25% and to less than 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 (particularly if there is evidence of proximal tubule dysfunction [e.g., hypophosphatemia] or worsening proteinuria).50 Tenofovir alafenamide is a TDF prodrug that is associated with less nephrotoxicity and is approved for use in coformulation with other antiretrovirals for eligible patients. Clinicians should be aware that some medications (cobicistat, dolutegravir, and trimethoprim) may affect creatinine secretion and elevate serum creatinine levels without affecting actual renal function.

GENITAL TRACT COMPLICATIONS

Prompt diagnosis of sexually transmitted infection is essential, and management in patients with HIV infection is typically similar to that in uninfected persons. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2015 guidelines on sexually transmitted infections provide information specific to patients with HIV infection.51 Persons with HIV infection have elevated rates of human papillomavirus infection, which increases the risk of anogenital tract dysplasia.52 Cervical cancer screening guidelines for women with HIV infection differ from those for average-risk women (Table 4).53 Screening should begin within one year of sexual activity onset, but no later than 21 years of age, and should continue through a woman's lifetime. Papanicolaou testing should be performed annually until three normal results have been obtained, then the interval can be extended to every three years. Women older than 30 years with negative results on human papillomavirus cotesting can be rescreened in three years.

| Age (years) | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| 21 to 29 | Pap testing should be performed at initial HIV diagnosis. If the results are normal, the next Pap test should be performed in 12 months. (Some experts recommend retesting six months after the baseline test.) If the results of three consecutive Pap tests are normal, follow-up Pap testing should be performed every three years. Cotesting (Pap and HPV tests) is not recommended. |

| 30 and older | Pap testing should be performed at initial HIV diagnosis, then every 12 months. (Some experts recommend retesting six months after the baseline test.) If the results of three consecutive Pap tests are normal, follow-up Pap testing should be performed every three years. If co-testing (Pap and HPV tests) is available, it can be done at the time of HIV diagnosis or at 30 years of age. Women with negative co-test results can undergo follow-up screening in three years. |

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has not addressed anal cancer screening, but the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends screening certain high-risk groups, including men who have sex with men, women with a history of receptive anal intercourse or abnormal cervical cytology, and all persons with HIV infection and genital warts.15 Human papillomavirus vaccination is recommended for appropriate age groups.53

Metabolic and Endocrine Complications

DYSLIPIDEMIA AND INSULIN RESISTANCE

Metabolic dysregulation resulting in lactic acidosis and lipodystrophy occurs less often with newer antiretrovirals. However, many currently used agents, HIV infection itself, and patient factors (including aging) are associated with dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Antiretrovirals with adverse effects on lipid levels include abacavir, efavirenz, boosted protease inhibitors, and elvitegravir/cobicistat.1 Patients should be screened for lipid and glucose disorders when HIV infection is diagnosed and routinely thereafter; some experts also recommend retesting after starting or modifying ART.15

Management of insulin resistance and diabetes in persons with HIV infection does not differ significantly from that in uninfected patients, and treatment should follow American Diabetes Association guidelines.54 Decisions about statin use should be made using standard risk calculators similar to those used for uninfected patients. However, caution should be used when prescribing statins with protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors because of the potential for serious drug interactions. Clinicians should consider switching ART combinations to more lipid- and/or glucose-neutral regimens if specific antiretroviral agents are suspected of causing or worsening significant hyperlipidemia or hyperglycemia.55

BONE METABOLISM

Studies show an increased risk of reduced bone mineral density and 10% to 50% increased fracture risk among persons with HIV infection.56,57 Several HIV-related and non–HIV-related factors (e.g., low weight, chronic inflammation, coinfections, nadir CD4 count, smoking, alcohol use, menopause) may have a role in bone metabolism. Additionally, ART initiation is associated with a 2% to 6% reduction in bone mineral density over the first two years of therapy.58 Almost all antiretrovirals have been implicated in bone changes—particularly TDF, efavirenz, and boosted protease inhibitors—and the largest decrease in bone mineral density occurs in the first six to 12 months of use. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may attenuate bone loss at ART initiation, although evidence from clinical trials is lacking.59

Experts suggest measuring bone mineral density in postmenopausal women, men 50 years and older, and others at high risk of osteoporotic fracture.58 For patients with osteopenia or osteoporosis, clinicians may consider switching to more bone-friendly regimens in addition to optimizing non–HIV-specific risk factors and initiating bisphosphonates as indicated. Osteomalacia and vitamin D deficiency, which occur in up to 80% of persons with HIV infection,60 should be identified and addressed before initiating bisphosphonates.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Chu and Selwyn,2 and by Reust.61

Data Sources: We performed bibliographic searches of select HIV and ART-related guidelines and expert panel/consensus practice recommendations to identify additional primary literature sources. We also searched the Cochrane database, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, Essential Evidence Plus, the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute/Johns Hopkins University HIV Clinical Resource guidelines, and UpToDate. PubMed was searched using the key terms HIV neurologic complications, HIV cardiovascular complications, HIV pulmonary complications, HIV gastrointestinal complications, HIV hepatic complications, HIV renal complications, and HIV metabolic complications. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Original research studies cited by key review articles identified through these searches were also reviewed. Search dates: January 2016 through May 2016.