Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(3):179-185

Patient information: See related handout on pelvic organ prolapse, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Pelvic organ prolapse is the descent of one or more of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, the uterus (cervix), or the apex of the vagina (vaginal vault or cuff scar after hysterectomy). Prevalence increases with age. The cause of prolapse is multifactorial but is primarily associated with pregnancy and vaginal delivery, which lead to direct pelvic floor muscle and connective tissue injury. Hysterectomy, pelvic surgery, and conditions associated with sustained episodes of increased intra-abdominal pressure, including obesity, chronic cough, constipation, and repeated heavy lifting, also contribute to prolapse. Most patients with pelvic organ prolapse are asymptomatic. Symptoms become more bothersome as the bulge protrudes past the vaginal opening. Initial evaluation includes a history and systematic pelvic examination including assessment for urinary incontinence, bladder outlet obstruction, and fecal incontinence. Treatment options include observation, vaginal pessaries, and surgery. Most women can be successfully fit with a vaginal pessary. Available surgical options are reconstructive pelvic surgery with or without mesh augmentation and obliterative surgery.

Pelvic organ prolapse is defined by herniation of the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, uterus, or vaginal apex into the vagina; descent may occur in one or more structures.1 Prolapse of pelvic structures can cause a sensation of pelvic pressure or bulging through the vaginal opening and may be associated with urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, fecal incontinence, incomplete defecation, and sexual dysfunction.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Women with pelvic organ prolapse should be evaluated for other pelvic floor disorders such as stress urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and fecal incontinence. | C | 19 |

| Women should be asked about symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse because they otherwise may not volunteer this information. | C | 23 |

| Most women should be offered a pessary as first-line treatment for pelvic organ prolapse. | C | 27 |

| Sexual function should be assessed before surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse. | C | 21, 22 |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not exclude pessaries as a treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse. | American Urogynecologic Society |

Epidemiology

Although pelvic organ prolapse can affect women of all ages, it more commonly occurs in older women. The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse increases with age until a peak of 5% in 60- to 69-year-old women.2 Some degree of prolapse is present in 41% to 50% of women on physical examination,3 but only 3% of patients report symptoms.2 Limited data suggest that prolapse progresses until menopause, with low rates of progression and regression thereafter.2,4,5 The number of women who have pelvic organ prolapse is expected to increase by 46%, to 4.9 million, by 2050.6

Terminology

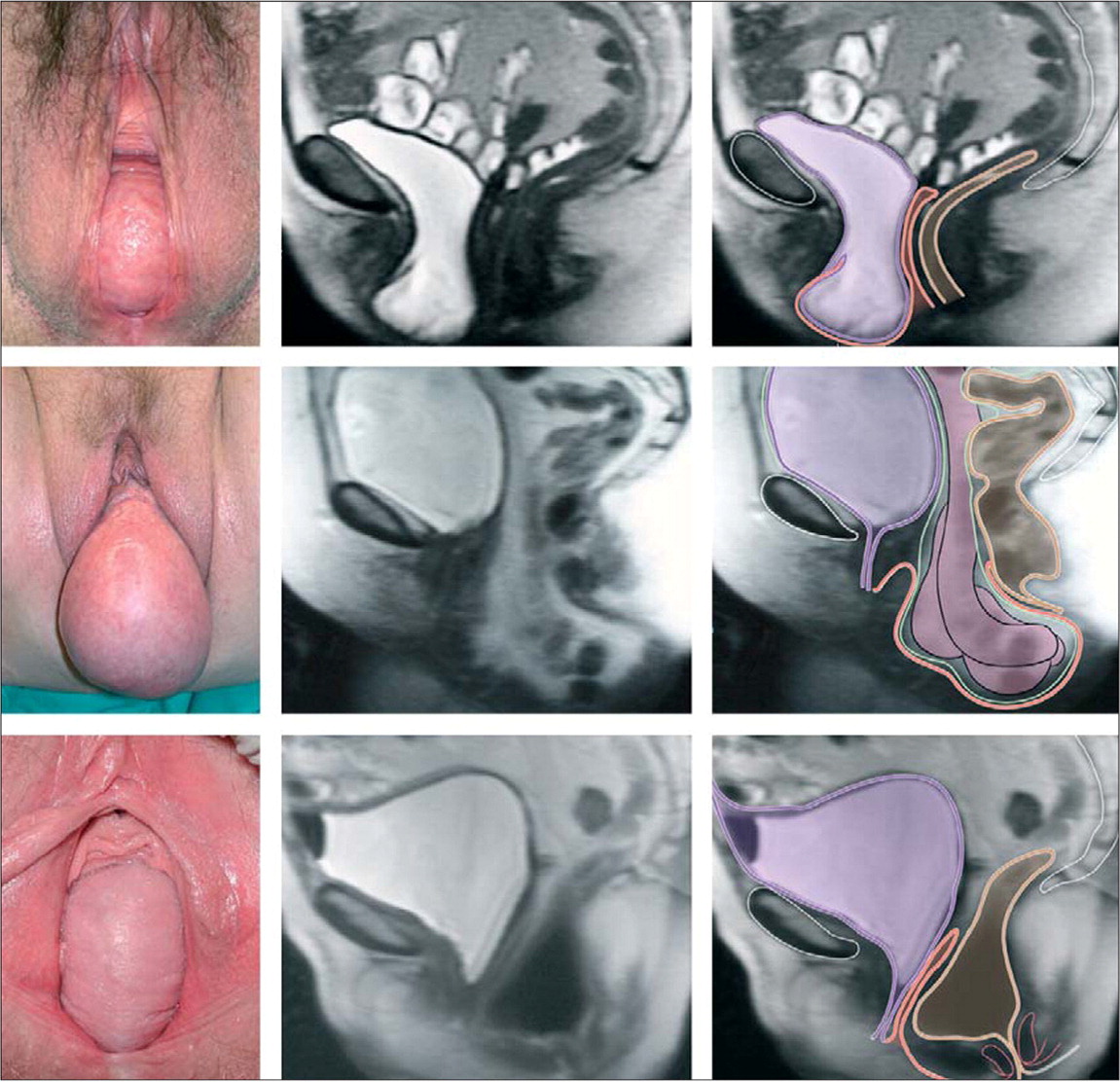

Current recommendations characterize the site of prolapse as the anterior vaginal wall, posterior vaginal wall, and vaginal apex (apical prolapse). Apical prolapse is sometimes referred to as uterine or cervical prolapse when these structures are present; after total hysterectomy, prolapse of the vaginal cuff is referred to as vaginal vault prolapse1 (Figure 17 ). Anterior prolapse is two and three times more common than posterior and apical prolapse, respectively.

Etiology

The cause of pelvic organ prolapse is multifactorial, but pregnancy is the most commonly associated risk factor. Normal pelvic support is primarily provided by the levator ani muscles and the connective tissue attachments of the vagina to the sidewalls and pelvis. With normal pelvic support, the vagina lies horizontally atop the levator ani muscles. When damaged, the levator ani muscles become more vertical in orientation and the vaginal opening widens, shifting support to the connective tissue attachments. Biomechanical modeling has demonstrated that during the second stage of labor, levator ani muscles are stretched more than 200% beyond the threshold for stretch injuries.8

A magnetic resonance imaging study of parous women revealed that those with prolapse within 1 cm of the hymen are 7.3 times more likely to have levator ani injuries than women without prolapse.9 Prospective ultrasound studies of initially nulliparous women revealed that the prevalence of levator ani injuries is 21% to 36% after vaginal delivery,10,11 and that these injuries correlate with prolapse symptoms.11 Of note, 17% of nulliparous women with prolapse have levator ani injuries visible on magnetic resonance imaging.9 Additional risk factors for prolapse are listed in Table 1.12–16

| Category | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity or race | Hispanic, white13,14 |

| General | Advancing age, parity, elevated body mass index, connective tissue disorders (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)15 |

| Genetics | Family history of prolapse15 |

| Increased intra-abdominal pressure | Chronic cough, constipation, repeated heavy lifting15 |

| Obstetric | Operative vaginal delivery,16 vaginal delivery15 |

| Previous surgery | Hysterectomy/previous prolapse surgery15 |

Clinical Presentation

HISTORY

Most patients with pelvic organ prolapse are asymptomatic. Seeing or feeling a bulge that protrudes to or past the vaginal opening is the most specific symptom.17 During a well-woman visit, questions such as “Do you see or feel a bulge in your vagina?” can provide screening for pelvic organ prolapse.3

Pelvic organ prolapse is dynamic, and symptoms and examination findings may vary day to day, or within a day depending on the level of activity and the fullness of the bladder and rectum. Standing, lifting, coughing, and physical exertion, although not causal factors, may increase bulging and discomfort. Patients with complete uterine prolapse (i.e., procidentia) may have vaginal discharge related to chafing or epithelial erosion.

Elevated body mass index is a risk factor for pelvic organ prolapse. In one study, women who were obese were more likely to have progression of prolapse by 1 cm or more in one year (odds ratio = 2.9).5 Weight loss does not reverse herniation.18 Prolapse often coexists with other pelvic floor disorders. Of those with prolapse, 40% have stress urinary incontinence, 37% have overactive bladder, and 50% have fecal incontinence. Patients who report experiencing any of these disorders should be evaluated for the others as well.19

Bladder outlet obstruction may occur because of urethral kinking or pressure on the urethra. Prolapse symptoms may not correlate with the location or severity of the prolapsed compartment.20 Patients with posterior vaginal prolapse sometimes use manual pressure on the perineum or posterior vagina (called splinting) to help complete evacuation of stool. Pelvic organ prolapse may negatively affect sexual activity, body image, and quality of life.21,22 Physicians must ask specific questions about pelvic floor disorders because patients often do not volunteer this information out of feelings of embarrassment and shame.23

EXAMINATION

When prolapse is suspected, a pelvic examination is required to fully characterize the location and extent of prolapse. First, the vaginal opening and perineal body are observed while the patient performs a Valsalva maneuver. A speculum is then inserted to visualize the vaginal apex (cervix or vaginal cuff), and vaginal length noted. The Valsalva maneuver is again performed and the speculum is slowly removed to observe apical descent. Next, the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are examined while the opposite wall is retracted using a one-blade speculum (e.g., Sims speculum). Measurements may be taken, and, using the pelvic organ prolapse quantification staging system or the Baden-Walker grading system (Table 224 ), the extent of the prolapse classified. Finally, assessment for infection, hematuria, and incomplete bladder emptying is necessary. A urine dipstick analysis and postvoid residual volume test, using either a voided specimen with bladder scanner or in-and-out catheter insertion, are appropriate for this purpose.

| Baden-Walker system | Pelvic organ prolapse quantification system | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Description | Stage | Description |

| 0 | Normal position for each respective site, no prolapse | 0 | No prolapse |

| 1 | Descent halfway to the hymen | I | Greater than 1 cm above the hymen |

| 2 | Descent to the hymen | II | 1 cm or less proximal or distal to the plane of the hymen |

| 3 | Descent halfway past the hymen | III | Greater than 1 cm below the plane of the hymen, but protruding no farther than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length |

| 4 | Maximal possible descent for each site | IV | Eversion of the lower genital tract is complete |

A rectal examination should be performed to assess sphincter tone. If no bulge is noted, or if the observed bulge does not correlate with the patient's symptoms, the patient should also be examined in the standing, straining position.

Further Evaluation

The need for additional evaluation depends on patient symptoms, stage of prolapse, and the proposed treatment plan. Up to one-half of women who undergo prolapse surgery may experience de novo stress urinary incontinence caused by urethral unkinking.25 Complex urodynamic testing performed while reducing the prolapse with swabs or a speculum may help predict which women will benefit from a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure.26 In cases of recurrent or unusual prolapse (e.g., large perineal bulge), defecation proctography or dynamic pelvic magnetic resonance imaging may be useful.

Treatment

Women with pelvic organ prolapse may elect for observation, pelvic floor muscle training, pessary use, or surgery. The primary goal of any treatment is to improve symptoms and, for conservative management, to minimize prolapse progression. The choice of treatment is driven by patient preferences; however, patients with symptomatic prolapse should be made aware that pessary use is a viable nonsurgical option.27

OBSERVATION

Most cases of pelvic organ prolapse do not require treatment; however, women with prolapse beyond the vaginal opening typically desire some intervention. Contraindications to expectant management are: (1) hydroureteronephrosis resulting from ureteral kinking with descent of the bladder, (2) recurrent urinary tract infections or ureteral reflux due to bladder outlet obstruction, and (3) severe vaginal or cervical erosions and infections. Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation and avoidance of heavy lifting and constipation may reduce symptoms.

PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLE TRAINING

Pelvic floor muscle training exercises (Kegel), the systematic contraction of the levator ani muscles, may improve pelvic function. Pelvic floor muscle training has been shown to improve symptoms associated with stress, urge, and mixed urinary incontinence 28 and may result in a small improvement in symptoms in women with mild prolapse. However, it does not reverse or treat pelvic organ prolapse.29 Good results are generally achieved with 45 to 60 exercises per day, divided into two to three sets.

PESSARIES

Pessaries are devices that are placed in the vagina to restore normal pelvic anatomy and decrease prolapse symptoms (Figure 2). They are primarily made from medical-grade silicone. Two-thirds of patients with pelvic organ prolapse initially choose management with a pessary,30 and up to 77% will continue pessary use after one year.31 Pessaries are an option for all stages of prolapse, and they may prevent progression of prolapse and avert or delay the need for surgery.32 Additionally, continence pessaries have a knob to coapt the urethra for treatment of stress incontinence.

Use of a pessary may be limited in patients with dementia or pelvic pain. Women with decreased dexterity may require office management of pessaries. These devices should not be placed in patients who are unlikely to adhere to instructions for care or follow-up because serious complications such as erosion into the bladder or rectum can result from pessary neglect.

Pessary Selection. Pessaries may be supportive or space occupying. The ring pessary, a supportive device, is the most commonly used pessary in the United States, followed by the space-occupying Gellhorn and donut pessaries (Figure 312 ). More advanced prolapse often requires space-occupying devices.33 However, the PESSRI trial, the only randomized controlled trial comparing pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse, reported no difference in patient symptoms between the ring and Gellhorn pessaries.34 Support pessaries can be inserted and removed by the patient, may allow for sexual intercourse, and are associated with less vaginal discharge and irritation compared with space-occupying pessaries.35

Pessary Fitting. More than 85% of patients who choose treatment with a pessary are successfully fit with one.36 Short vaginal length, wide vaginal opening (greater than four fingerbreadths), and history of hysterectomy are risk factors for fitting failure.33 Fitting is performed through trial and error. Most physicians initially try a ring pessary (Table 312 ). A ring pessary is folded in half for insertion and should fit between the pubic symphysis and posterior vaginal fornix. The pessary should remain more than one fingerbreadth above the introitus when the patient bears down. The patient should walk, sit, and void with the pessary in place to assess comfort and retention. Once the appropriate fit is obtained, instructions on insertion and nightly removal and cleaning should be provided to the patient. Less frequent removal at weekly, biweekly, or monthly intervals is also acceptable.

Follow-up. Patients should return one to two weeks after their pessary fitting to assess satisfaction with the device and symptom improvement. Thereafter, women who perform self-care may return annually for examination. Other women should generally return every three months for pessary removal, cleaning, and examination.

The most common complications of pessary use are vaginal discharge, irritation, ulceration, bleeding, pain, and odor. Bacterial vaginosis occurs in up to 30% of patients who have a pessary and is more common with less frequent pessary removal.37 Vaginal ulceration and bleeding occur more commonly in postmenopausal women and with less frequent pessary removal; vaginal estrogen therapy is commonly prescribed for treatment and prevention of vaginal ulceration and irritation. A recent randomized controlled trial of hydroxyquinoline-based gel (Trimosan gel) for prevention of bacterial vaginosis found that a higher proportion of women using hormone therapy had vaginal sores.37 Additionally, a retrospective cohort study found that vaginal estrogen therapy was not protective against vaginal ulcerations or bleeding.38 Women with vaginal bleeding and an intact uterus and no obvious ulceration require further evaluation for endometrial pathology.

REFERRAL

Primary care physicians should feel comfortable with screening for prolapse, performing a basic evaluation, and, depending on training, pessary management. Women who require more advanced evaluation and treatment should be referred to a gynecologic subspecialist with board certification in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery.

SURGERY

Obliterative and reconstructive surgeries for pelvic organ prolapse are available and may include hysterectomy or uterine conservation (hysteropexy). The decision for surgery must include a discussion of a patient's goals and expectations based on cultural views such as body image and desire for future sexual function, including vaginal intercourse.21,22 Vaginal obliteration (colpocleisis) has the highest cure rate and lowest morbidity of any surgical intervention and is an excellent option for women who do not desire any future vaginal intercourse. For women who prefer to maintain coital function, reconstructive surgery should be performed and the vaginal apex can be suspended using the woman's own tissues and sutures (native tissue repair), or mesh can be placed abdominally, to suspend the top of the vagina to the sacrum (sacrocolpopexy), or transvaginally (transvaginal mesh).

| Trial | Pessary type |

|---|---|

| 1 | Ring with support |

| Ring with support and knob, if urinary incontinence is present | |

| 2 | Gellhorn |

| 3 | Donut |

| 4 | Combination of pessaries: ring plus Gellhorn, ring plus donut, or two donuts; use ring with support and knob, if urinary incontinence is present |

| 5 | Cube or Inflatoball |

Transvaginal mesh prolapse repairs have been intensely scrutinized. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an advisory recommending that physicians discuss potential complications of vaginal mesh for prolapse with patients.39 It is important to note that synthetic mesh for suburethral slings and sacrocolpopexy is not included in the advisory. The American Urogynecologic Society and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a joint statement in 2011 in which they agreed that use of transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse should be reserved for complex patients, such as those with advanced or recurrent prolapse or medical conditions that make more invasive and lengthier open or endoscopic procedures too risky.40 The Pelvic Floor Disorders Registry (https://www.augs.org/clinical-practice/pfd-research-registry/), created by the American Urogynecologic Society for the purpose of surveillance of transvaginal mesh implants, also collects validated objective outcome measures and electronic patient-reported outcomes.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Kuncharapu, et al.12

Data Sources: We searched PubMed and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews using the following keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, prolapse, pessary, cystocele, rectocele, and vaginal vault prolapse. The search included review articles and was limited to English language studies. Search dates: March 8, 2016, and April 6, 2016.