Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(11):720-728

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Hoarseness is a common presentation in primary care practices. Combined with other voice-related changes, it falls under the umbrella diagnosis of dysphonia. Hoarseness has a number of causes, ranging from simple inflammatory processes to less common psychiatric disorders to more serious systemic, neurologic, or cancerous conditions. Medication-induced hoarseness is common and should be considered. The initial evaluation begins with a targeted history and physical examination, while also looking for signs of potential systemic etiologies. Treatment should begin with voice rest, especially avoidance of whispering, and conservative management directed toward a presumptive cause. For example, proton pump inhibitors are appropriate for hoarseness due to reflux, and proper vocal hygiene is recommended for vocal abuse–related indications. In the absence of a clear indication, antibiotics, oral corticosteroids, and proton pump inhibitors should not be used for the empiric treatment of hoarseness. Direct visualization of the larynx and vocal folds, commonly mislabeled as vocal cords, should be performed within three months if an etiology has not been determined or if conservative management has been ineffective. Patients who experience symptoms lasting longer than two weeks and who have risk factors for dysplasia (e.g., tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, hemoptysis) may require earlier laryngoscopic evaluation. Voice therapy is effective for improving voice quality in patients with dysphonia if conservative measures are unsuccessful, and it can also be helpful for prophylaxis in high-risk individuals (e.g., vocalists, public speakers). Surgical management is indicated for laryngeal or vocal fold dysplasia or malignancy, airway obstruction, or benign pathology resistant to conservative treatment.

Hoarseness is a common symptom in adults, with a lifetime prevalence of 30% and a point prevalence of 7% for adults 65 years and younger. Most never seek treatment, with only 6% of patients presenting to a health care professional.1 However, hoarseness still constitutes a common out-patient concern and can significantly impact patients' voice-related quality of life and limit their productivity.2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Examination of the larynx by direct or indirect laryngoscopy should be performed on patients with hoarseness lasting longer than two weeks without an apparent benign etiology. | C | 3 |

| In the absence of signs and symptoms suggestive of an underlying cause, antibiotics, oral corticosteroids, and proton pump inhibitors should not be used for the empiric treatment of laryngitis/hoarseness. | C | 3 |

| If laryngopharyngeal or gastroesophageal reflux is suspected, consider a trial of a high-dose proton pump inhibitor for three to four months. | C | 26 |

| Voice therapy is effective for improving voice quality and vocal performance in patients with nonorganic dysphonia. | A | 20 |

| Voice therapy is effective for treating benign vocal fold nodules, polyps, cysts, and granulomas. | B | 29–31 |

| Vocal hygiene education is effective for treating patients with hoarseness. | B | 29, 32 |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not perform computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a primary complaint of hoarseness before examining the larynx. | American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation |

The term hoarseness is commonly used to describe any change in voice but more specifically refers to a coarse, rough, raspy, or strangled vocal quality. It includes any change in pitch, loudness, or vocal effort that impairs vocal function. The presence of hoarseness warrants investigation to determine an underlying cause.3

Laryngeal Anatomy and Function

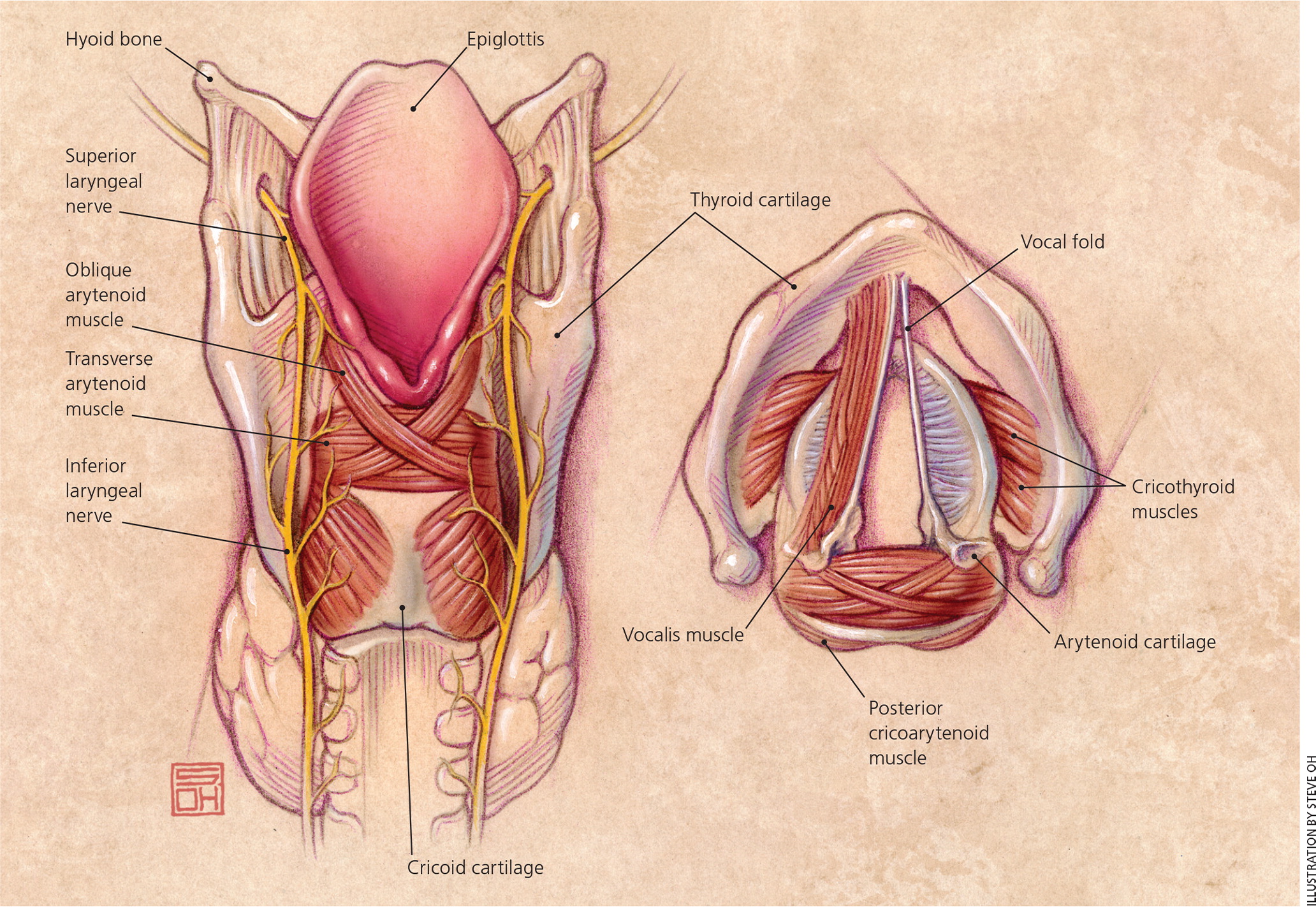

The larynx functions in vocalization, deglutition, and respiration. It consists of an inner, mucosal-lined soft tissue framework protected by cartilaginous and bony structures (Figure 1).4 Extending from tongue base to trachea, it can be divided into three sections: supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic. The supraglottis, protected by the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage, ranges from the tongue base to just above the true vocal folds (commonly mislabeled as vocal cords), and contains the epiglottis, false vocal folds, and arytenoids. The glottis, protected by the thyroid cartilage, extends inferiorly 1 cm below the true vocal folds. The subglottis extends from the inferior glottis to just below the cricoid cartilage.

The larynx contains extrinsic and intrinsic muscles innervated by two nerves branching from the vagus on each side: the superior laryngeal nerve and the recurrent (or inferior) laryngeal nerve. The internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve enters the supraglottis between the hyoid and thyroid cartilage, and the external branch enters the glottis laterally through the cricothyroid membrane. The recurrent laryngeal nerves ascend lateral to the trachea after recurring upward around the aortic arch on the left and the subclavian artery on the right to ultimately enter the glottis through the cricothyroid membrane. The extrinsic muscles elevate and lower the position of the larynx in the neck. The intrinsic muscles produce fine movements of the vocal folds for phonation, and except for the cricothyroid muscles, are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerves.

The larynx produces sounds by forcing air through partially closed vocal folds to create vibrations of the folds. The intrinsic muscles control the tension of the vocal folds to create a wide range of sound waves, and the positioning of other speech organs such as the lips, tongue, and soft palate modifies these waves to increase the range of sounds.

Causes of Hoarseness

Dysphonia (i.e., voice impairment) can result from any pathology affecting these complex mechanisms of vocalization, but hoarseness primarily results from vocal fold changes. Causes of hoarseness can be grouped into four categories: irritant/inflammatory, neoplastic, neuromuscular/psychiatric, and associated systemic disease. Common and important causes are listed in Table 1.4

| Inflammatory or irritant |

| Allergies and irritants (alcohol, tobacco) |

| Direct trauma (intubation) |

| Environmental irritants |

| Infections (upper respiratory infection, fungal laryngitis) |

| Laryngopharyngeal or gastroesophageal reflux |

| Medications |

| Vocal abuse |

| Neoplasia or physical lesions |

| Benign vocal fold lesions |

| Dysplasia |

| Laryngeal papillomatosis |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Neuromuscular and psychiatric |

| Age-related vocal atrophy |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Muscle tension dysphonia |

| Myasthenia gravis |

| Nerve injury (vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve) |

| Parkinson disease |

| Psychogenic (including conversion aphonia) |

| Spasmodic dysphonia (laryngeal dystonia) |

| Stroke |

| Associated systemic diseases |

| Acromegaly |

| Amyloidosis |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Inflammatory arthritis |

| Lupus |

| Sarcoidosis |

INFLAMMATORY AND IRRITANT CAUSES

The most common cause of hoarseness in adults is laryngitis, which is classified as acute or chronic. Acute laryngitis is a common, self-limited condition lasting less than three to four weeks. Common causes include acute vocal strain or upper respiratory infection. Short-term vocal abuse (e.g., singing, screaming) or protracted coughing can cause microtrauma and focal vocal fold edema. Hoarseness is often part of a constellation of upper respiratory symptoms caused by viruses and less commonly by bacterial or fungal sources.5 Allergic rhinitis is another common cause of acute laryngitis.

Chronic laryngitis is diagnosed when symptoms persist for more than three to four weeks. Long-term inhalation of irritants (usually through smoking), reflux, chronic vocal strain, and postnasal drip are common causes. Irritation of vocal fold mucosa by reflux can be caused by laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Medications are another common cause of chronic laryngitis,6–9 particularly those classes listed in Table 2.3

| Medication | Mechanism of impact on voice |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Cough |

| Antihistamines, diuretics, anticholinergics | Drying effect on mucosa |

| Antipsychotics, including atypical antipsychotics | Laryngeal dystonia |

| Bisphosphonates | Chemical laryngitis |

| Danazol, testosterone | Sex hormone production/utilization alteration |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | Dose-dependent mucosal irritation, candidal or fungal laryngitis |

| Warfarin (Coumadin), thrombolytics, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors | Vocal fold hematoma |

NEOPLASIA AND PHYSICAL LESIONS

Vocal fold lesions may be benign or malignant. More common benign lesions include Reinke edema (also known as polypoid chorditis), cysts, pseudocysts, polyps, and nodules (also known as midfold masses).10 Some benign lesions have a higher prevalence based on factors such as age and sex (Table 3).10–13

| Lesion type | Laryngoscopic findings | Common characteristics and associations | Etiologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral midfold masses (includes nodules) | Subepithelial fibrous thickening at vocal fold midpoint | Female, 18 to 39 years of age | Vocal abuse |

| Contact lesion (ulceration or granuloma) | Mucosal irregularity over vocal process of arytenoid cartilage | Male, unilateral or bilateral | Direct trauma (intubation), inhaled corticosteroid use, LPR, vocal abuse |

| Cyst | Encapsulated subepithelial mass | Unilateral | Vocal abuse |

| Hemorrhage | Subepithelial extravasated blood | Unilateral | Vocal abuse, direct trauma, anticoagulant use |

| Leukoplakia | White-appearing epithelia of vocal fold | Male, older age (60 years and older) | Benign leukoplakia, carcinoma, dysplasia |

| Polyp | Well-defined sessile or pedunculated midpoint mass | Male, unilateral | Allergy, tobacco and other irritants, vocal abuse |

| Pseudocyst | Translucent lesion on vibratory margin | Female, 18 to 39 years of age, unilateral | Vocal abuse, vocal fold paresis |

| Reactive lesion | Focal mucosal thickening in vocal fold midpoint | Unilateral, contralateral lesion | Trauma by contralateral vocal fold lesion |

| Reinke edema (polypoid chorditis) | Proliferation of superficial mucosa over entire length of one or both vocal folds | Female, middle-aged (40 to 59 years) or older age (60 years and older), bilateral more common | GERD, LPR, tobacco and other irritants, vocal abuse |

| Sulcus | Focal epithelial invagination | Male, bilateral | Congenital |

| Unilateral midfold masses (includes nodules) | Subepithelial fibrous thickening at vocal fold midpoint | Male, less common than bilateral | Vocal abuse |

Premalignant or malignant vocal fold lesions include laryngeal leukoplakia, dysplasia, and squamous cell carcinoma. Smoking, alcohol abuse, LPR, and GERD are risk factors for more serious underlying causes such as malignant lesions.3 Hoarseness alone or other related symptoms (e.g., dysphagia, odynophagia, otalgia, hemoptysis, unilateral throat pain) may be the initial presentation of these lesions, particularly in middle-aged or older persons who smoke.3,14,15

NEUROMUSCULAR AND PSYCHIATRIC CAUSES

Vocal fold paralysis is a common neurologic cause of hoarseness. Unilateral paralysis is typically caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve injury during neck, thyroid, or cardiothoracic surgery, but many times it is idiopathic.16 Unilateral paralysis can also be associated with infiltrating thyroid or apical lung cancers.12,13 Bilateral vocal fold paralysis is typically associated with bilateral thyroid surgery or neck trauma resulting in bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. Prolonged or traumatic endotracheal intubation can cause vocal fold inflammation and paralysis. Presbylaryngis, or age-related vocal atrophy, is increasingly common with an aging population, and can mimic fold paralysis as laryngeal muscles atrophy despite intact innervation.17 Less common neurologic causes include myasthenia gravis, Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis.

Spasmodic dysphonia (or laryngeal dystonia) is the episodic, uncontrolled contraction of laryngeal intrinsic muscles to create a halting, strangled voice. Once considered psychogenic because of its relation to stress, the underlying neuromuscular etiology remains unknown.18 Considered neuropsychiatric in nature, muscle tension dysphonia results from excessive tension of the intrinsic or extrinsic muscles, and is associated with lack of breath control and stress.19 Psychiatric or functional voice disorders include functional dysphonia, laryngeal conversion disorder, paradoxical vocal fold motion, and malingering. Functional dysphonia occurs in patients with job-related chronic vocal stress without organic cause. Conversion disorder and paradoxical fold motion are psychogenic responses to stress.20

ASSOCIATED SYSTEMIC DISEASES

Less commonly, hoarseness occurs secondary to systemic illnesses. Autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory arthritis and lupus, can affect the cricoarytenoid joints. Endocrine disorders, including hypothyroidism and acromegaly, can cause hoarseness. Sarcoidosis and laryngeal amyloidosis are rare etiologies that strain voice quality from infiltration of the vocal folds and supraglottic structures.21

Evaluation of Hoarseness

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The first step in evaluating hoarseness should be assessing vocal quality, speech effort, or signs of pain with speaking or swallowing, followed by the history, including specific changes in vocal quality (Table 4).4 Timing, onset, duration, and exacerbating or remitting factors can be key to determining the etiology. The presence of any associated symptoms, especially for GERD, LPR, or postnasal drip, should be elicited. Symptoms of LPR include dysphagia, burning in the throat, globus sensation, throat clearing, or a sensation of postnasal drainage. GERD and LPR can occur together or separately. A review of medications is imperative because multiple drug classes have been associated with dysphonia9 (Table 23). Acute onset is more suggestive of infection, inflammation, injury, or vocal abuse (e.g., singing or screaming at a sporting event or concert), whereas a chronic or progressive change in phonation can indicate more severe illness.

| Vocal quality | Suggested diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Breathy | Inflammatory arthritis, spasmodic or functional dysphonia, vocal fold mass, vocal fold paralysis |

| Halting, strangled | Spasmodic dysphonia |

| Hoarse, husky, muffled, or nasal-sounding | Parkinson disease |

| Hoarseness worse early in the day | GERD, LPR |

| Hoarseness worse later in the day | Myasthenia gravis, vocal abuse |

| Low pitched | GERD, hypothyroidism, LPR, leukoplakia, muscle tension dysphonia, Reinke edema, vocal fold edema, age-related vocal atrophy in women |

| Raspy or harsh | GERD, LPR, muscle tension dysphonia, vocal fold lesion |

| Scanning speech and dysarthria | Multiple sclerosis |

| Soft (loss of volume) | Vocal fold paralysis, Parkinson disease, age-related vocal atrophy |

| Spoken voice lost, but whispered voice maintained | Conversion aphonia |

| Strained | GERD, LPR, muscle tension dysphonia, spasmodic dysphonia |

| Strained, effortful phonation | Muscle tension dysphonia |

| Thick, deep voice and slowed speech | Acromegaly |

| Vocal fatigue | Muscle tension dysphonia, myasthenia gravis, Parkinson disease, vocal abuse, age-related vocal atrophy |

Patients should be asked about voice use and other related symptoms and factors (Table 5).4 For example, do they use their voice frequently in their occupation (e.g., singing, public speaking, telemarketing, teaching) or recreation (e.g., umpiring, coaching)? Is their voice change constant, progressive, or relapsing/remitting? 4

| Findings | Suggested causes |

|---|---|

| Cough | Allergy, GERD, inhaled irritants, LPR, tobacco, URI |

| Dysphagia | Carcinoma, GERD, inflammatory arthritis, LPR |

| Heartburn | Carcinoma, GERD, LPR |

| Hemoptysis | Carcinoma |

| History of heavy alcohol use | Carcinoma, GERD, LPR |

| History of smoking or tobacco use | Carcinoma, chronic laryngitis, leukoplakia, Reinke edema |

| Odynophagia | Carcinoma, inflammatory arthritis, URI |

| Palpable lymph nodes | Carcinoma, URI |

| Professional vocalist or untrained singer | Vocal abuse |

| Recent head, neck, or chest surgery | Vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve injury |

| Recent intubation or laryngeal procedure | Direct trauma with vocal fold paralysis |

| Rhinorrhea, sneezing, watery eyes | Allergy, URI |

| Sensitivity to heat, spicy foods, other irritants | Leukoplakia |

| Stridor, symptoms of airway obstruction | Carcinoma, laryngeal papillomatosis |

| Throat clearing | Allergy, GERD, inhaled corticosteroids, LPR |

| Weight loss | Carcinoma |

| Wheezing, other signs of asthma | Allergy, inhaled corticosteroids |

OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Hoarseness of acute onset with a duration of less than 14 days and an apparent benign cause requires no further initial evaluation. Laryngoscopy should be performed if serious pathology is suspected, or it can be considered if dysphonia persists longer than two weeks, especially in patients with risk factors for dysplasia such as tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, or hemoptysis.3 Visualization by direct or indirect methods should not be delayed beyond three months for patients who remain symptomatic. Table 310–13 and Table 64 highlight laryngoscopic findings for a variety of conditions. Figure 2 outlines a suggested approach to the primary care management of hoarseness.4 Referral for imaging studies (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) or biopsy may be indicated if laryngoscopy is nondiagnostic.3 Laryngoscopy and pH monitoring are not reliable tests for diagnosing LPR. Videostroboscopy, which uses strobe lighting during laryngoscopy, can further visualize mucosal vibration disorders (e.g., scar, sulcus) if conventional laryngoscopy is inconclusive.22,23 Speech-language pathology offers perceptual, acoustic, and aerodynamic evaluations if examination and imaging are insufficient for making a diagnosis.24

| Findings | Etiologies |

|---|---|

| Cysts | Vocal abuse |

| Exophytic or ulcerated lesions | Carcinoma |

| Granulomas | Direct trauma (intubation), GERD, inhaled corticosteroids, LPR, vocal abuse |

| Laryngeal inflammation | Allergy, direct trauma (intubation), GERD, infection, inhaled corticosteroids, LPR, tobacco and other irritants |

| Leukoplakia | Benign leukoplakia, carcinoma, dysplasia |

| Loss of vocal fold adduction during phonation, but normal adduction with coughing or throat clearing | Conversion aphonia |

| Nodules | Vocal abuse |

| Papillomas | Laryngeal papillomatosis (human papillomavirus infection) |

| Polyps | Allergy, tobacco and other irritants, vocal abuse |

| Reinke edema (polypoid chorditis) | GERD, LPR, tobacco and other irritants, vocal abuse |

| Translucent, yellow, waxy deposits on vocal folds | Laryngeal amyloidosis |

| Ulceration and laceration | Direct trauma (intubation) |

| Vocal fold in paramedian or lateralized position | Vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, stroke |

Treatment

Voice rest, especially the avoidance of whispering, is essential for the treatment of hoarseness. Neither antibiotics nor corticosteroids should be routinely prescribed empirically.3,25 A three- to four-month regimen of high-dose proton pump inhibitors should be prescribed only if the history indicates GERD or LPR, or if signs of chronic laryngitis are visualized.3,26,27 Inhaled corticosteroids, notably fluticasone (Flovent), budesonide (Rhinocort), and beclomethasone, can cause dysphonia in up to 58% of persons, more so in women (3:2 ratio) and individuals older than 65 years.9,28 Gargling, rinsing the mouth, or drinking water, as well as using a spacer, may be tried if dysphonia develops, and the corticosteroids can be discontinued or given at a reduced dosage if the hoarseness fails to resolve with these simple measures.9

Voice therapy, or voice training, is strongly recommended for patients with hoarseness who have significantly impaired vocal quality of life, especially those with dysphonia of nonorganic origins, benign vocal fold lesions, or age-related vocal atrophy.3,20,24,29–32 It can also be preventive in high-risk individuals such as vocalists and public speakers.12,29 Therapy regimens consist of vocal behavior modification to reduce laryngeal trauma during weekly 30- to 60-minute sessions for eight to 10 weeks. Compliance with vocal hygiene (e.g., avoiding irritants and alcohol, using a humidifier, controlling vocal volume, limiting large or spicy meals), vocal and physical exercises, and behavior change are imperative.29,32

Surgical intervention is needed for dysplastic or malignant lesions, airway obstruction, or benign lesions (e.g., nodules, polyps, cysts) that do not respond to conservative therapies. Botulinum toxin can be used for the management of adductor spasmodic dysphonia.33 Vocal fold paralysis can be treated with laryngeal reinnervation or vocal fold medialization procedures.34

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Feierabend and Malik,4 and Rosen, et al.35

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms hoarseness and dysphonia. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, reviews, and clinical practice guidelines. Additionally, Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the DynaMed database, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines were used. Search dates: November 30, 2015; March 25, 2016; and May 9, 2017.