Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(2):86-93

An updated article on Heel Pain is available.

Related letter: Consider Muscle Strengthening for Plantar Fasciitis

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

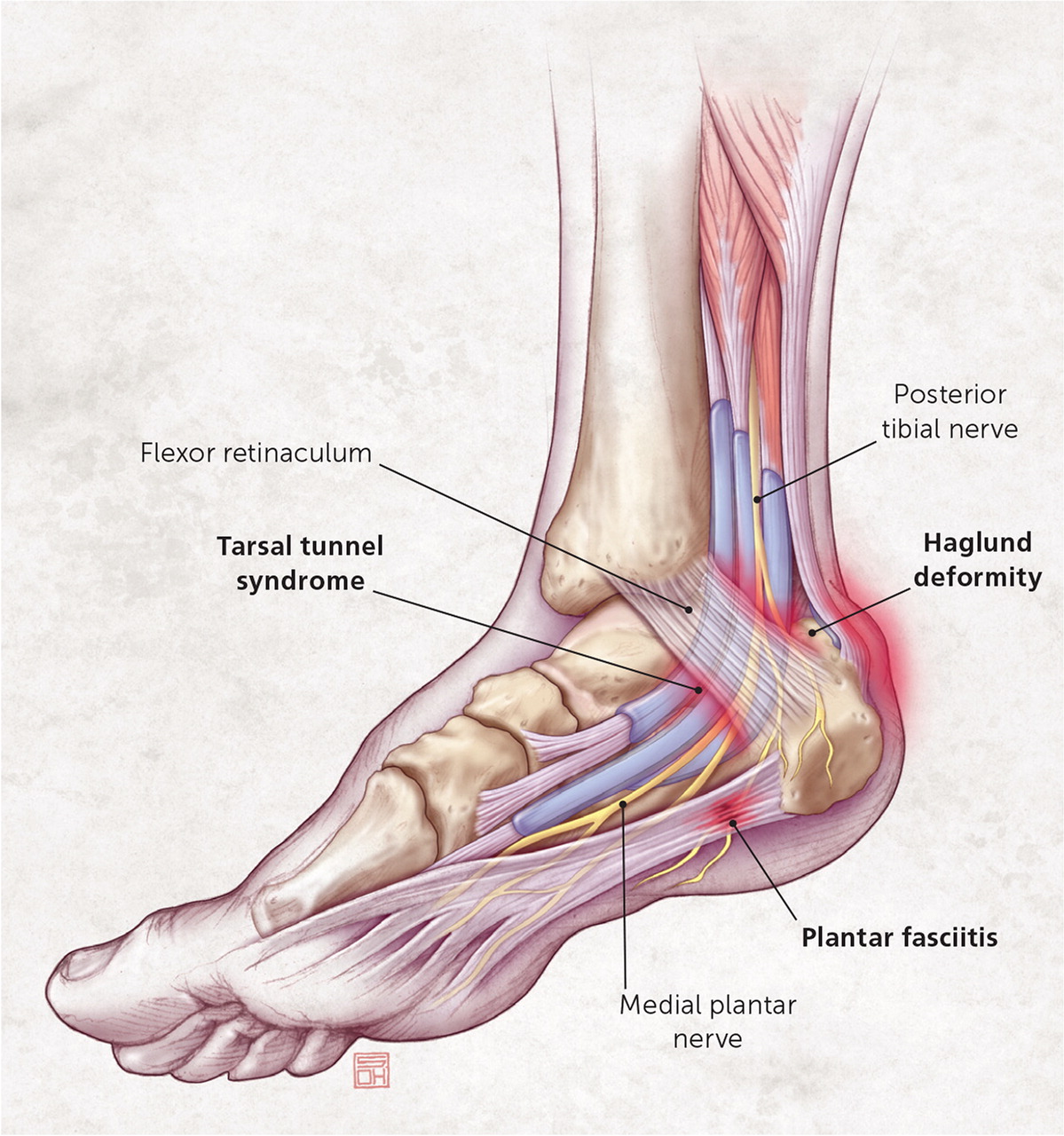

The differential diagnosis of heel pain is extensive, but a mechanical etiology is the most common. The specific anatomic location of the pain can help guide diagnosis. The most common diagnosis is plantar fasciitis, which leads to medial plantar heel pain, especially with the first weight-bearing steps after rest. Other causes of plantar heel pain include calcaneal stress fractures (progressively worsening pain after an increase in activity or change to a harder walking surface), nerve entrapment or neuroma (pain accompanied by burning, tingling, or numbness), heel pad syndrome (deep, bruise-like pain in the middle of the heel), and plantar warts. Achilles tendinopathy is a common cause of posterior heel pain; other tendinopathies result in pain localized to the insertion site of the affected tendon. Posterior heel pain can also be attributed to Haglund deformity (a prominence of the calcaneus that may lead to retrocalcaneal bursa inflammation) or Sever disease (calcaneal apophysitis common in children and adolescents). Medial midfoot heel pain, particularly with prolonged weight bearing, may be due to tarsal tunnel syndrome, which is caused by compression of the posterior tibial nerve. Sinus tarsi syndrome manifests as lateral midfoot heel pain and a feeling of instability, particularly with increased activity or walking on uneven surfaces.

Heel pain is a common presenting symptom to family physicians and has an extensive differential diagnosis (Table 1).1 Most diagnoses stem from a mechanical etiology (Table 2).1 A thorough patient history, physical examination of the foot and ankle,2 and appropriate imaging studies are essential in making a correct diagnosis and initiating proper management. The history should provide information about the onset and characteristics of the pain, alleviating or exacerbating factors, changes in activity, and other related conditions.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid and platelet-rich plasma injections can reduce pain from plantar fasciitis, especially when performed with ultrasound guidance. | A | 5, 8–11 |

| Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is a treatment option for chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinopathy. | B | 5, 6, 12, 26 |

| Bone scans, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging is often needed to diagnose calcaneal stress fractures because radiography does not always reveal a fracture. | C | 15, 16 |

| Duct tape occlusion is ineffective for the treatment of plantar warts. | A | 21 |

| Radiographic findings of spurring at the Achilles tendon insertion site or intratendinous calcifications are indicative of Achilles tendinopathy. | C | 13 |

| Corticosteroid or platelet-rich plasma injections should not be used to treat Achilles tendinopathy. | A | 22, 24 |

| Radiography is typically not helpful in diagnosing Sever disease. | C | 1, 30, 31 |

| Arthritic | |||

| Fibromyalgia | |||

| Gout | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathies | |||

| Infectious | |||

| Diabetic ulcers | |||

| Osteomyelitis | |||

| Plantar warts | |||

| Mechanical (Table 2) | |||

| Neurologic | |||

| Lumbar radiculopathy (L4-S2) | |||

| Nerve entrapment (branches of posterior tibial nerve) | |||

| Neuroma | |||

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome (posterior tibial nerve) | |||

| Trauma | |||

| Tumor (rare) | |||

| Ewing sarcoma | |||

| Neuroma | |||

| Vascular (rare) | |||

| Etiology | Clinical features | Initial treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Plantar | ||

| Plantar fasciitis/fasciosis | Pain with first steps after prolonged rest | Relative rest |

| Tenderness on medial calcaneal tuberosity and along plantar fascia | Activity modification | |

| Stretching/strengthening exercises | ||

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Ice massage | ||

| Arch support | ||

| Heel spurs | Radiographic findings at site of pain | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Calcaneal stress fracture | Follows increase in activity level or change to harder walking surfaces | Activity modification with occasional non–weight-bearing activity |

| Pain with activity progressively worsens to pain at rest | Heel pads or walking boots | |

| Diagnosed with imaging | ||

| Nerve entrapment (medial or lateral plantar nerve, nerve to abductor digiti minimi) | Sensations of burning, tingling, or numbness | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Occasionally preceded by increased activity or trauma | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| Ice | ||

| Stretching exercises | ||

| Neuroma | Sensations of burning or tingling | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Painful lump with palpation | ||

| Heel pad syndrome | Deep, bruise-like pain and tenderness at middle of heel | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Heel cups | ||

| Taping | ||

| Proper footwear | ||

| Posterior | ||

| Achilles tendinopathy | Achy, occasionally sharp pain | Activity modification |

| Worsens with increased activity or pressure to area | Decrease pressure to affected area | |

| Tenderness along tendon | Heel lifts/orthotics | |

| Occasional palpable prominence from tendon thickening | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| Worsens with passive dorsiflexion | Deep friction massage | |

| Tendon mobilization | ||

| Eccentric exercises | ||

| Haglund deformity | Pain at the superior aspect of the posterior calcaneus | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Radiographic diagnosis | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| Retrocalcaneal bursitis | Pain, erythema, and swelling around Achilles tendon | Decrease pressure to affected area |

| Tenderness on direct palpation | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| Corticosteroid injections (preferably ultrasound guided) | ||

| Sever disease (calcaneal apophysitis) | Pain in adolescents that worsens with increased activity or during growth spurt | Activity modification |

| Tenderness at Achilles insertion | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| Pain with passive dorsiflexion and mediolateral calcaneal compression | Ice | |

| Stretching/strengthening exercises | ||

| Orthotics/shoe modifications | ||

| Midfoot (medial) | ||

| Posterior tibialis tendinopathy | Tenderness at navicular and medial cuneiform | Activity modification |

| Decrease pressure to affected area | ||

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Eccentric exercises | ||

| Flexor digitorum longus tendinopathy | Tenderness posterior to medial malleolus and obliquely across sole of foot to base of distal phalanges of lateral toes | Activity modification |

| Decrease pressure to affected area | ||

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Eccentric exercises | ||

| Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy | Tenderness posterior to medial malleolus and on plantar surface of great toe | Activity modification |

| Decrease pressure to affected area | ||

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Eccentric exercises | ||

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome | Burning, tingling, or shooting pain and numbness in posteromedial ankle and heel (may extend into toes) that worsens with standing and activity | Activity modification |

| Positive Tinel sign | Orthotics | |

| Muscle atrophy in severe cases | Neuromodulatory/anti-inflammatory medication | |

| Corticosteroid injections | ||

| Midfoot (lateral) | ||

| Peroneal tendinopathy | Tenderness in lateral calcaneus along path to base of fifth metatarsal | Activity modification |

| Decrease pressure to affected area | ||

| Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | ||

| Eccentric exercises | ||

| Sinus tarsi syndrome | Pain in lateral calcaneus and ankle | Orthotics |

| Feeling of foot/ankle instability | Ice massage | |

| Worse after exercise or on uneven surfaces | Anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication | |

| May have history of repeated ankle sprains | Physical therapy (balance/proprioception, strengthening exercises) | |

| Corticosteroid injections | ||

The anatomic location of the pain can be a guide to diagnosis (Figure 1 and Figure 2).1 Examination should include inspection of the foot at rest and when weight bearing, as well as palpation of bony prominences, tendon insertions, and the foot and ankle joints. Any tenderness, defects, or differences between the sides should be noted. Active range of motion of the foot and ankle should be assessed; if full range of motion is not present, passive range of motion should also be evaluated. Specific testing, as detailed throughout this article, will also help determine the diagnosis.

Plantar Heel Pain

PLANTAR FASCIITIS

More than 2 million persons present with plantar heel pain every year.1 Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause, with a lifetime prevalence of 10% in the general population.3,4 The primary symptom is usually throbbing medial plantar heel pain that is worse with the first steps after rest. The pain often decreases after further ambulation, but can return with continued weight bearing. Palpation of the medial calcaneal tuberosity and along the plantar fascia typically causes sharp, stabbing pain (Figure 2).1 Passive dorsiflexion of the foot and toes often elicits pain as well.5 Diagnostic imaging is not required, but weight-bearing radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography can help rule out other causes of heel pain.3,5 Heel spurs are present in approximately 50% of patients with plantar fasciitis, but they do not correlate well with symptoms and can also be found in persons without plantar fasciitis.5

Initial treatment is typically conservative, with rest, activity modification, stretching, strengthening exercises, ice massage, and use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications.1,4,5 Custom or prefabricated orthotics, arch taping, night splinting, and physical therapy are effective and can be combined with more conservative approaches.4–7 Corticosteroid and platelet-rich plasma injections—particularly when performed with ultrasound guidance—can provide short-term pain relief and are often used when conservative measures are ineffective or more immediate pain control is desired.5,8–11 Corticosteroid injections increase the risk of plantar fascia rupture or fat pad atrophy. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy and plantar fasciotomy can be used to treat recalcitrant cases.5,6,12–14

CALCANEAL STRESS FRACTURE

Calcaneal stress fractures are caused by repetitive overload to the heel and most commonly occur immediately inferior and posterior to the posterior facet of the subtalar joint.15 Pain usually begins after an increase in weight-bearing activities or after changing to a harder walking surface. The pain initially occurs only with activity, but it can later occur at rest. Swelling or ecchymosis may be noted on examination, with point tenderness at the fracture site. A positive calcaneal squeeze test (i.e., pain on squeezing the sides of the calcaneus) suggests the diagnosis. Radiography often does not reveal a fracture, so bone scans, computed tomography, or MRI may be required15,16 (Figure 31 ). Activity modification, with little to no weight bearing for up to six weeks if pain is severe, is usually successful.15,16 Heel pads or walking boots can also be used. Calcaneal stress fractures tend to heal well in otherwise healthy patients.

NEUROPATHIC ETIOLOGIES

Heel pain accompanied by burning, tingling, or numbness may suggest a neuropathic etiology, either with nerve entrapment or the development of a neuroma. Nerve entrapment can be caused by overuse, trauma, or injury from a previous surgery.17,18 Neuropathic plantar heel pain typically involves branches of the posterior tibial nerve, the lateral plantar nerve, or the nerve to the abductor digiti minimi (Figure 2).1 Lumbar radiculopathy at the L4-S2 levels should also be considered regardless of the presence of associated low back pain. Neuropathic heel pain is usually unilateral, and underlying systemic disease should be ruled out in patients with bilateral pain.13 MRI and ultrasonography may be helpful in visualizing the nerve entrapment.19 Treatment initially involves rest, ice, use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications, relief of pressure at the pain site, and stretching.17,18 Surgical decompression should be considered if conservative treatment is ineffective.

Neuromas can also develop on branches of the tibial nerve. The pain may be mistaken for plantar fasciitis, although it sometimes has a more burning or tingling sensation. Palpation at the neuroma site may reveal a painful lump. Neuromas should be considered when treatment for plantar fasciitis is ineffective.1,18

HEEL PAD SYNDROME

Pain from heel pad syndrome is described as a deep, bruise-like pain, usually in the middle of the heel, and can be reproduced with firm palpation. Pain may be elicited by walking barefoot, on harder surfaces, or for prolonged periods.20 This syndrome is typically caused by inflammation but can also be due to damage to or atrophy of the heel pad. Decreased heel pad elasticity from aging, prior corticosteroid injections, or increased body weight may also contribute.1,20 Treatment is aimed at decreasing pain with rest, ice, taping, and the use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications, heel cups, and proper footwear.

PLANTAR WARTS

Plantar warts, which are raised skin lesions resulting from infection with the human papillomavirus, can cause heel pain. Lesions can be noted on inspection of the heel and may be tender to palpation. They are usually self-limited; however, patients often desire quicker resolution. Over-the-counter medications, cryotherapy, topical medications, laser therapy, and shaving the wart are effective treatments but may worsen pain in the short term.21 Occlusion with duct tape has not been proven effective for plantar warts.21

Posterior Heel Pain

ACHILLES TENDINOPATHY

The Achilles tendon is formed from the merging of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles, and it inserts into the calcaneus.22 Excessive mechanical loading of the muscle, such as with increased running, can cause tendinopathy that leads to posterior heel pain. The pain associated with Achilles tendinopathy is achy, occasionally sharp, and worsens with increased activity or pressure to the area.13,22 Fluoroquinolone use has been shown to precipitate Achilles tendinopathy, particularly in older persons.23 The diagnosis can be classified as insertional or within the midsubstance of the tendon.13,22,24 Palpation should reveal tenderness along the tendon and sometimes a prominence from tendon thickening. Passive dorsiflexion of the ankle increases pain. Radiography may demonstrate spurring at the tendon insertion or intratendinous calcifications.13 Ultrasonography may demonstrate thickening of the tendon (Figure 4).1

Effective treatments include activity modification, eccentric exercises, reduction of pressure to the area, deep friction massage, tendon mobilization, and use of analgesic medications and heel lifts or other orthotic devices.22,25 Some studies have shown benefit with extracorporeal shock wave therapy 26 and nitroglycerin patches.27 Kinesiology taping 28 and corticosteroid or platelet-rich plasma injections 22,24 have been found ineffective for Achilles tendinopathy. Injections, particularly with corticosteroids, should be avoided because of the risk of tendon rupture. Severe cases may require surgery.

HAGLUND DEFORMITY

A Haglund deformity is a prominence of the superior aspect of the posterior calcaneus (Figure 21 and eFigure A) that is most common in middle-aged women.29 Repeated pressure from ill-fitting footwear or the deformity itself can cause retrocalcaneal bursitis.13,29 Patients with retrocalcaneal bursitis have erythema and swelling over the bursa and tenderness to direct palpation. Treatment is aimed at decreasing pressure and inflammation and may include wearing open-heeled shoes, corticosteroid injections (preferably with ultrasound guidance), physical therapy, and use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications.13,29 In refractory cases, surgery may be necessary to remove the deformity.13,29

SEVER DISEASE

The most common etiology of heel pain in children and adolescents is Sever disease (calcaneal apophysitis). Patients usually present between eight and 12 years of age with activity-associated heel pain, particularly with running or jumping,30 that is often worse at the beginning of a new sports season or during a growth spurt.31 Pain may be elicited by palpation around the Achilles insertion site, with mediolateral calcaneal compression, and with passive dorsiflexion.30,31 Radiographic findings are typically normal but may show fragmented or sclerotic calcaneal apophysis.1 Treatment is conservative and includes limiting of pain-inducing activities, use of anti-inflammatory or analgesic medications, ice, stretching and strengthening the gastrocnemius-soleus complex, and shoe modifications with orthotics, heel cups, or lifts.30,31

Midfoot Heel Pain

TENDINOPATHIES

Other, less common tendinopathies can cause heel pain localized to the insertion site of the affected tendon. Medial heel pain may be triggered by the posterior tibialis, flexor digitorum longus, or flexor hallucis longus tendon.1 Lateral heel pain can originate from the peroneal tendon. Ultrasonography of these tendons may aid in the diagnosis.32 Treatment is similar to that of Achilles tendinopathy.

TARSAL TUNNEL SYNDROME

The tarsal tunnel is a fibro-osseous space formed by the flexor retinaculum, medial calcaneus, distal tibia, posterior talus, medial malleolus, and abductor hallucis.17,18 Compression of the posterior tibial nerve through the tarsal tunnel causes burning, tingling, shooting pain, or numbness in the posteromedial ankle and heel, and sometimes into the distal sole and toes.17,18,33 It can also lead to cramping of the medial longitudinal arch.33 This syndrome can be caused by trauma, space-occupying lesions, poor biomechanics, or systemic disease.18,33

Patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome often report worsening of pain with standing, walking, or running, and relief with rest, elevation, and use of loose-fitting footwear. Examination may reveal pes planus or another deformity, malalignment, or muscle atrophy in severe cases.18 The pain can be reproduced by tapping along the course of the nerve (Tinel sign) and with provocative maneuvers to stress or compress the nerve (dorsiflexion-eversion test, plantar flexion-inversion test).18,33 MRI is the preferred diagnostic test for tarsal tunnel syndrome,33 but ultrasonography, electromyography, and nerve conduction studies may also be useful.18,33 Treatment is typically conservative and consists of activity modification, corticosteroid injections, biomechanical interventions, and use of oral or topical anti-inflammatory medications, orthotic devices, and neuromodulator medications (tricyclics and antiepileptics). Surgery can be considered if conservative measures are ineffective.17,18,33

SINUS TARSI SYNDROME

The sinus tarsi, or talocalcaneal sulcus, is an anatomic space bound by the calcaneus, talus, talocalcaneonavicular joint, and posterior facet of the subtalar joint. Sinus tarsi syndrome can be caused by a single traumatic event, repeated lateral ankle sprains, or repeated hyperpronation of the foot, leading to instability of the subtalar joint.32,34 Patients with sinus tarsi syndrome typically present with pain in the lateral calcaneus and ankle accompanied by a feeling of foot and ankle instability that is provoked by running, cutting and jumping, walking on uneven surfaces, or even stepping off a curb.32,34 Imaging may include MRI or radiography with stress views.34 Treatment includes ice, massage, taping, balance and proprioceptive training, muscle strengthening, corticosteroid injections (eFigure B), and use of anti-inflammatory medications, ankle braces, and orthotics.1,34 Surgery is usually required in patients for whom rehabilitation has been ineffective.34

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Tu and Bytomski1 ; Aldridge35 ; and Barrett and O'Malley.36

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term heel pain in combination with each etiology discussed in the article, with occasional use of the key words diagnosis, treatment, and management. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Searches were also performed in Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine and British Journal of Sports Medicine (both through the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine website). Search dates: September, November, and December 2016; and October 2017.