Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(9):576-585

Related letters: Lyme Disease As Possible Contributing Factor for Knee Pain and Thessaly vs. McMurray Test for Diagnosis of Meniscal Injuries

Patient information: See related handout on knee pain.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Knee pain affects approximately 25% of adults, and its prevalence has increased almost 65% over the past 20 years, accounting for nearly 4 million primary care visits annually. Initial evaluation should emphasize excluding urgent causes while considering the need for referral. Key aspects of the patient history include age; location, onset, duration, and quality of pain; associated mechanical or systemic symptoms; history of swelling; description of precipitating trauma; and pertinent medical or surgical history. Patients requiring urgent referral generally have severe pain, swelling, and instability or inability to bear weight in association with acute trauma or have signs of joint infection such as fever, swelling, erythema, and limited range of motion. A systematic approach to examination of the knee includes inspection, palpation, evaluation of range of motion and strength, neurovascular testing, and special (provocative) tests. Radiographic imaging should be reserved for chronic knee pain (more than six weeks) or acute traumatic pain in patients who meet specific evidence-based criteria. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography allows for detailed evaluation of effusions, cysts (e.g., Baker cyst), and superficial structures. Magnetic resonance imaging is rarely used for patients with emergent cases and should generally be an option only when surgery is considered or when a patient experiences persistent pain despite adequate conservative treatment. When the initial history and physical examination suggest but do not confirm a specific diagnosis, laboratory tests can be used as a confirmatory or diagnostic tool.

Knee pain affects approximately 25% of adults. The prevalence of knee pain has increased almost 65% over the past 20 years, accounting for nearly 4 million primary care visits annually.1,2 The initial evaluation should emphasize excluding urgent causes while considering the need for referral. A standardized, comprehensive history and physical examination are crucial for differentiating the diagnosis. Nonsurgical problems do not require immediate definitive diagnosis. Imaging and laboratory studies can play a confirmatory or diagnostic role when appropriate. This article reviews the initial primary care office evaluation of undifferentiated knee pain in adults and adolescents (ages 11 to 17 years), highlighting key patient history and physical examination findings (Table 11,3–27). The uses of and indications for radiography, musculoskeletal ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and laboratory evaluation are also addressed.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal derangement should be suspected in patients with knee trauma and acute effusion. | C | 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 14, 19, 30 | Rapidity of effusion should be noted. |

| In patients with suspected meniscal injury, the Thessaly test is preferred over the McMurray test or other evaluation for joint-line tenderness. | C | 3, 4, 6, 7, 12, 14, 16, 25, 30, 31, 34 | Thessaly may be difficult to perform in an acute setting because of pain and feeling of instability. |

| The Ottawa Knee Rule should be used to determine which patients with acute knee injury require imaging. | A | 11, 16, 17, 29, 30, 36–38 | — |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid ordering knee magnetic resonance imaging for a patient with anterior knee pain without mechanical symptoms or effusion unless the patient has not improved after completion of an appropriate functional rehabilitation program. | American Medical Society for Sports Medicine |

| Condition | Historical points | Physical examination tests and/or findings |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical (acute) | ||

| Collateral ligament sprain or rupture (MCL, LCL)3–7 | Medial or lateral pain | Pain with applied force |

| Injury from valgus (MCL) or varus (LCL) force | Asymmetric gapping or laxity | |

| Associated internal derangements | ||

| Cruciate ligament sprain or rupture (ACL, PCL)3–6,8–13 | ACL

| ACL

|

PCL

| PCL

| |

| Medial plica syndrome3–7 | Acute (or chronic) medial pain | Tender mobile tissue band along medial joint line |

| Overuse; onset of new activities | ||

| May report mechanical symptoms (e.g., catching, clicking) | ||

| Meniscal tear 3,5,6,9–17 | Male; age > 40 years | Thessaly test |

| Cutting or twisting injury while bearing weight | McMurray test | |

| Effusion in 24 to 48 hours | Joint-line tenderness | |

| Locking or giving way | Loss of extension (locked) | |

| Patellar subluxation or dislocation3–5,8 | Anterior pain | Apprehension |

| Children or adolescents | Laxity | |

| History of subluxation | Effusion | |

| Mechanical (chronic) | ||

| Distal patellar apophysitis (Sinding-Larsen-Johannson syndrome)8,18 | Adolescents (10 to 13 years of age) | Tenderness of inferior pole of patella |

| Repetitive running, jumping, or squatting | Local soft tissue swelling | |

| Decreased flexibility of quadriceps and hamstrings on affected side | ||

| Iliotibial band syndrome3–5,7 | Lateral knee pain | Poor hamstring flexibility |

| Repetitive flexion | Pain along entirety of iliotibial band | |

| Runners, cyclists | ||

| Meniscal derangement or tear5,6,9–12,14–17,19 | Overuse | Thessaly test |

| Medial or lateral pain | McMurray test | |

| Advanced osteoarthritis | ||

| Osteoarthritis1,3–5,20–22 | Diffuse pain | Chronic bony deformity |

| Stiffness when initiating movement | Leg asymmetry | |

| Exacerbated by bearing weight | Appreciable crepitus | |

| Age > 50 years | ||

| Absence of trauma | ||

| Inflammatory signs | ||

| Pain worse at end of day | ||

| Patellofemoral pain syndrome (chondromalacia patellae)3,18,23–25 | Anterior pain | Patellar tilt test |

| Runners, cyclists | Inhibition “shrug” test | |

| “J” sign (abnormal tracking) | ||

| Poor vastus medialis oblique tone | ||

| Patellar grind | ||

| Pes anserine bursitis3–7,18 | Medial (or anteromedial) knee pain | Tender nodule overlying anteromedial proximal tibia |

| Overuse | ||

| Quadriceps or patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee)3–5,8,18,26 | Anterior pain | Pain specific to the quadriceps or patellar tendon |

| Athletes | ||

| Overuse and repetitive stress | ||

| Tibial apophysitis (Osgood-Schlatter disease)4,8,18,26 | Adolescents; associated with growth spurt | Tenderness at tibial tubercle |

| Anterior pain; atraumatic | ||

| Inflammatory (noninfectious) | ||

| Crystal-induced arthropathy (gout or pseudogout)3,5,6,9,11,15,27 | Acute, atraumatic, monoarticular pain | Limited flexion/extension |

| Fever is possible | Possible effusion and erythema | |

| Older adults (> 60 years) | Arthrocentesis demonstrating crystals on microscopy | |

| Risk factors for gout: male or postmenopausal female, high intake of purine-rich foods, critical illness, specific medications | Gout: negative birefringence | |

| Risk factors for pseudogout: hyperparathyroidism, hemochromatosis, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, osteoarthritis | Pseudogout: positive birefringence | |

| Inflammatory (infectious) | ||

| Septic joint5,6,9,11,15 | Acute/subacute | Limited flexion/extension |

| Systemic symptoms | Effusion and erythema | |

| Joint swelling, pain, erythema, warmth, and joint immobility | Arthrocentesis with Gram stain and culture | |

| Elevated white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein | ||

History

When evaluating knee pain, key aspects of the patient history include age; location, onset, duration, and quality of pain; mechanical or systemic symptoms; history of swelling; description of any precipitating trauma; and pertinent previous medical or surgical procedures. Patients requiring urgent referral generally have severe pain, immediate swelling, and instability or inability to bear weight in association with acute trauma, which suggests fracture, dislocation, or tendon or ligamentous rupture. Referral is also indicated for possible joint infection signs such as fever, swelling, and erythema with limited range of motion.

PAIN LOCATION

Anterior. Isolated anterior knee pain suggests involvement of the patella, patellar tendon, or its attachments. Anterior knee pain that is dull or aching and exacerbated by prolonged sitting or climbing stairs is common in patellofemoral pain syndrome.3,18 Athletes or other adults with overuse from running or jumping sports can develop quadriceps or patellar tendinopathy (commonly known as jumper's knee). Insidious onset of anterior knee pain in adolescents during rapid growth periods with concomitant overuse suggests Osgood-Schlatter disease (tibial apophysitis) or Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome (distal patellar apophysitis). Prepatellar bursitis causes patella-localized pain and swelling and can occur with isolated blunt trauma, repetitive injury, or infection of the overlying skin.18

Medial or Lateral. Medial or lateral knee pain with corresponding joint-line tenderness can result from acute injury or chronic overuse and may indicate meniscal derangement or a sprain or rupture of a collateral ligament.3,18 Pes anserine bursitis is a common cause of medial knee pain instigated by overuse or blunt injury; the pain is exacerbated by flexion and extension of the knee. Adolescents experiencing medial knee pain with or without concurrent hip pain should be evaluated for slipped capital femoral epiphysis, caused by a fracture through the femoral physis (growth plate).26 Chronic lateral knee pain in runners or cyclists (or stemming from other activities involving repetitive knee flexion) is a common presentation of iliotibial band syndrome.3

Posterior. Isolated posterior knee pain is less common but may occur from a symptomatic popliteal (Baker) cyst.3,28 Posterior knee pain after acute trauma raises suspicion for injury of the posterior cruciate ligament and posterior portions of the meniscus, quadriceps tendons, or neurovascular structures.28 Chronic posterior knee pain can suggest hamstring tendinopathy.28

Diffuse. Chronic, diffuse knee pain in adults older than 50 years is commonly attributable to degenerative knee osteoarthritis, particularly when the pain is worse at the end of the day, is exacerbated by weight-bearing activity, and is relieved by rest.20 Acute onset of diffuse atraumatic knee pain (within hours or days) may indicate an infectious etiology, gout, or rheumatoid arthritis; the latter is especially suspected when the pain is bilateral or when it occurs simultaneously in other joints. In adolescents, atraumatic or unexplained diffuse knee pain that worsens with activity warrants imaging to assess for osteochondrosis8; similar pain that persists at rest or that worsens at night should raise suspicion for malignancy.26

MECHANICAL SYMPTOMS

Mechanical symptoms, such as locking, buckling, or catching, suggest internal derangement and possible instability but can also occur in medial plica syndrome18 (Table 11,3–27). A popping sensation at the time of injury may occur in meniscal or ligamentous tears. A knee that is “locked” in flexion and that cannot be extended should be examined for a meniscal tear.4,14,15

SWELLING

If the patient has an acute injury, a knee joint effusion strongly suggests internal derangement.14,26 Swelling that occurs immediately (minutes to a few hours) after injury suggests a ligament rupture, intra-articular fracture, or patellar dislocation; swelling that appears within hours to a few days suggests a meniscal tear.15,19 Atraumatic swelling with erythema or palpable warmth implies gout or pseudogout, arthritic flare, or infection. Swelling that is limited to the borders of the patella suggests prepatellar bursitis.4,14,15

MECHANISM OF INJURY

When determining the mechanism of injury, gather information about pain onset, positioning of the knee during and after the injury, and subsequent weight-bearing status (Table 11,3–27). Meniscal tears commonly result from twisting injuries in the weight-bearing knee. Ligamentous rupture may result from excess deceleration force applied to a weight-bearing, fixed, lower extremity or a direct blow to the lateral or medial knee. A fracture should be considered when patients are unable to walk or limp at least four steps both immediately after injury and at first presentation.9,29,30

MEDICAL OR SURGICAL HISTORY

Family physicians should ask patients about previous knee or other joint pain, injuries, or surgeries. Physicians should also inquire about systemic medical conditions (e.g., autoimmune or infectious diseases, sexually transmitted infections) and review family history of autoimmune and degenerative conditions. Personal history of knee injury or surgery and family history of knee osteoarthritis or joint replacement are established risk factors for knee osteoarthritis.20,21 Additional risk factors for knee osteoarthritis include age older than 50 years, female gender, and being overweight.20

Physical Examination

A systematic approach to examination of the knee includes inspection, palpation, range of motion and strength evaluation, neurovascular assessment, and special (provocative) tests.

INSPECTION

Erythema, swelling, bruising, lacerations, gross deformity, discoloration, and any asymmetry of bony or soft tissue landmarks, including atrophy and valgus or varus deformities, should be noted.

PALPATION

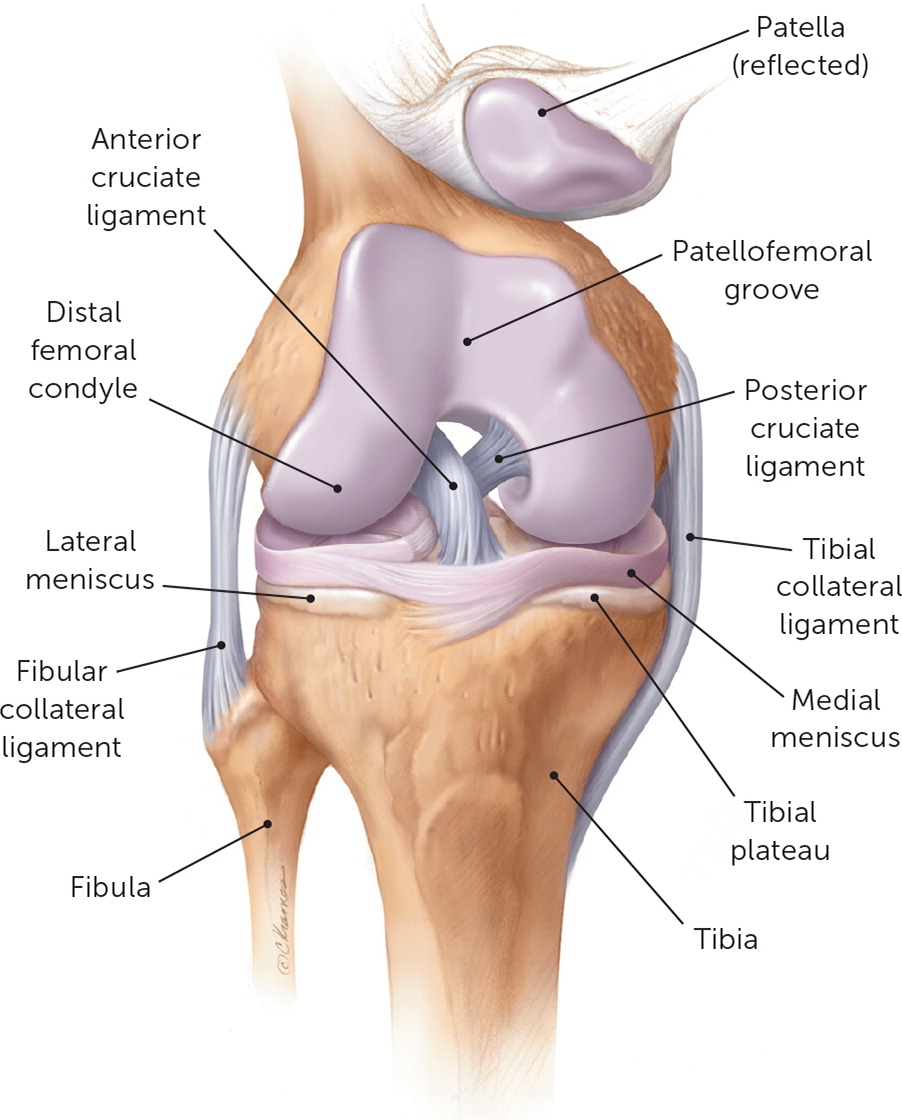

Palpation should assess for pain over all bony and soft tissue landmarks (Figure 131), warmth, and effusion. Pes anserine bursitis manifests as a tender nodule over the medial proximal tibia approximately 3 cm distal to the joint line, while a plica can be appreciated as a thin band of tissue most commonly near or overlying the medial joint line. A joint that is as warm or warmer than the tissue above or below that joint indicates infection or inflammation. An evaluation for effusion with the ballottement test and “milking” of the suprapatellar pouch should be conducted with the patient supine with the injured knee in extension.3

RANGE OF MOTION AND STRENGTH TEST

Range of motion (active and then passive) and strength testing (graded 0 to 5) should be used to assess flexion and extension of the knee. Normal limits of knee range of motion include extension from 0 to −10° and flexion to 135°.5 The examiner should assess for a lateral patellar tracking (“J” sign) vs. normal patellofemoral tracking during the range of motion examination23,24,32,33 (see figure in previous AFP article).

NEUROVASCULAR ASSESSMENT

Neurovascular examination of the knee includes assessment of sensation to light touch; deep tendon reflexes (graded 0 to 4+) of the patellar and Achilles tendons; and bilateral palpation of the popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses (graded 0 to 4+).10

SPECIAL (PROVOCATIVE) TESTS

| Maneuver or clinical findings | Positive likelihood ratio* | Negative likelihood ratio* | Probability of injury if maneuver is† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | |||

| Anterior cruciate ligament tear | ||||

| Pivot shift test | 20.3 | 0.4 | 69 | 4 |

| Lachman test | 12.4 | 0.14 | 58 | 2 |

| Anterior drawer test | 3.7 | 0.6 | 29 | 6 |

| Effusion | ||||

| Ballottement test; noticeable swelling | 3.6 | 0.4 | NA | NA |

| Meniscal tear | ||||

| Thessaly test | 39.3 | 0.09 | 81 | 1 |

| McMurray test | 17.3 | 0.5 | 66 | 5 |

| Age > 40, continuation of activity not possible, weight bearing during trauma, and pain with passive flexion5 | 5.8 | 0.9 | 39 | 9 |

| Joint-line tenderness | 1.1 | 0.8 | 11 | 8 |

Patellar Apprehension Test. This test involves laterally shifting the patella and is a variant of the patellar mobility test; both of these tests evaluate for patellar subluxation6 (see figure in previous AFP article). Patellar tilt and patellar grind (or inhibition) testing (see figure in previous AFP article) can indicate patellofemoral pain syndrome, as can assessment of core stability while the patient completes a single leg squat.

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| Anterior cruciate ligament tear | |

| Anterior drawer test* | With the patient supine on the examining table, flex the hip to 45° and the knee to 90°. Sit on the dorsum of the foot, wrap hands around the hamstrings (ensuring that these muscles are relaxed), then pull and push the proximal part of the leg, testing the movement of the tibia on the femur. Do these maneuvers in three positions of tibial rotation: neutral, 30° externally rotated, and 30° internally rotated. A normal test result is no more than 6 to 8 mm of laxity. |

| Lachman test* | With the patient supine on the examining table and the leg slightly externally rotated and flexed (20 to 30°) at the examiner's side, stabilize the femur with one hand and apply pressure to the back of the knee with the other hand, with the thumb on the joint line. A positive test result is movement of the knee with a soft or mushy end point. |

| Pivot shift test* | Fully extend the knee and rotate the foot internally. Apply a valgus (abduction) force while progressively flexing the knee, watching and feeling for translation of the tibia on the femur. |

| Posterior cruciate ligament tear | |

| Posterior drawer test | The patient should be supine on the examining table with knees flexed to 90°. While standing at the side of the examination table, the physician looks for posterior displacement of the tibia (posterior “sag” sign).4,6,34 The physician then fixes the patient's foot in neutral rotation (by sitting on the foot), positions thumbs at the tibial tubercle, and places fingers at the posterior calf. The physician then pushes posteriorly and assesses for posterior displacement of the tibia. |

| Gravity “sag” sign near extension test Active reduction “quad activation” of posterior tibial subluxation | In a resting position with the distal femur on a 15-cm support and the heel resting on the examination table (20° of flexion), the unsupported proximal tibia displays a concave anterior contour. When the patient raises the heel 2 to 3 cm, a normal anterior contour is restored. |

| Meniscal tear | |

| Joint-line tenderness | Palpate medially or laterally along the knee to the joint line between the femur and tibial condyles. Pain on palpation is a positive finding. |

| McMurray test† | Flex the hip and knee maximally. Apply a valgus (abduction) force to the knee while externally rotating the foot and passively extending the knee. An audible or palpable snap or click with pain during extension suggests a tear of the medial meniscus. For the lateral meniscus, apply a varus (adduction) stress during internal rotation of the foot and passive extension of the knee. |

| Thessaly test‡ | Hold patient's outstretched hands while the patient stands flat footed on the floor, internally and externally rotating the affected leg three times with the knee flexed 20°. The unaffected leg should be flexed to avoid contact with the floor. Patient-reported pain at the medial or lateral joint line is a positive finding. |

| Effusion | |

| Ballottement test§ | Push the patella posteriorly with two or three fingers using a quick, sharp motion. In the presence of a large effusion, the patella descends to the trochlea, strikes it with a distinct impact, and flows back to its former position. |

Gravity “Sag” Sign Near Extension, Active Reduction “Quad Activation” of Posterior Tibial Subluxation, and Posterior Drawer Tests. These tests evaluate for posterior collateral ligament (PCL) injury6,34 (Table 34,6,11,34). In one study, the sag sign correctly diagnosed PCL injury in 20 of 24 patients, and “quad activation” correctly identified PCL injury in 18 of 24 patients35 (see figure in previous AFP article).

Thessaly and McMurray Tests. The Thessaly test (Figure 311) is preferred over the McMurray test (see figure in previous AFP article) during the initial evaluation for meniscal injury; however, the effectiveness of both tests is often limited because of the patient's pain and inability to fully bear weight. A positive McMurray test (reported pain plus palpable click or clunk) substantially increases the probability of a meniscal tear because this test has high specificity (97%) but low sensitivity (52%).7,12,16,17

Valgus and Varus Stress Tests. No systematic review has addressed the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination findings in patients with medial or lateral collateral ligament injuries. The most common types of physical examination tests for assessing these injuries are the valgus and varus stress tests. Asymmetric gapping or laxity is suggestive of this injury6,11,20,34 (Figure 46).

Imaging

RADIOGRAPHY

Although a comprehensive history and physical examination are the mainstays of the initial evaluation, radiography may be necessary to further evaluate undifferentiated knee pain. However, with a 2% prevalence of fractures in outpatient primary care settings and a low diagnostic yield for clinically significant fractures, radiography should be reserved for chronic knee pain of more than six weeks duration or acute traumatic pain in patients who meet specific evidence-based criteria.11,36

The American College of Radiology Appropriateness criteria, the Ottawa Knee Rule, and the Pittsburgh Knee Rule provide support for imaging decisions. The Ottawa Knee Rule is a validated tool (98.5% to 100% sensitivity, 49% specificity) that decreases unnecessary radiography by 28% to 35% in the patient with an acutely injured knee.11,29,31,37–40 A prospective validation trial comparing the Ottawa Knee Rule and the Pittsburgh Knee Rule showed that each rule is useful, but the Pittsburgh rule appears to be more sensitive. Specifically, the Ottawa rule had a sensitivity of 97% (95% confidence interval [CI], 90% to 99%) and specificity of 27% (95% CI, 23% to 30%), whereas the Pittsburgh Knee Rule yielded a sensitivity of 99% (95% CI, 94% to 100%) and specificity of 60% (95% CI, 56% to 64%)30 (Table 411).

| Indication | ACR Criteria | Ottawa Knee Rule | Pittsburgh Knee Rule |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age < 12 or > 50 years | X | ||

| Age ≥ 55 years | X | ||

| Altered mental status | X | ||

| Fall or blunt trauma | X | ||

| Inability to bear weight for four steps (unable to transfer weight twice) immediately after injury or in the emergency setting | X | X | X |

| Inability to flex knee to 90° | X | X | |

| Joint effusion within 24 hours of a direct blow or fall | X | ||

| Tenderness over head of fibula or isolated to patella without other bony tenderness | X | X |

The three recommended radiographic views are anteroposterior view, lateral view, and Merchant's view (for the patellofemoral joint).30,40 Oblique views can assess for tibial plateau fractures, and the notch or tunnel (intracondylar) view can visualize osteochondral lesions.4 If osteoarthritis is suspected, weight-bearing radiographs should be obtained to assess for joint-space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, and bony cysts.4,22

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Musculoskeletal ultrasonography performed by a trained clinician13,25,41,42 allows for limited evaluation of effusions, cysts (e.g., Baker) and superficial tendons, collateral ligaments, muscles, vasculature, and nerves. In particular, dynamic evaluation of the extensor mechanism (quadriceps tendon, patella, and patellar tendon) can be readily assessed. Mechanical complaints such as snapping, clicking, or popping can be evaluated through palpation with an ultrasound transducer.40

MRI

Emergent MRI is rarely indicated and is typically reserved for potential surgical indications such as dislocation, ACL or PCL tear, fracture not visible on radiography, vertical meniscal tear, malignancy, vascular injury, or osteomyelitis. Ideally, MRI will confirm the findings from the history and physical examination. MRI also may be useful if mechanical symptoms (such as locking, painful clicking, or inability to fully extend the knee) occur or if recurrent swelling or persistent pain is present after a trial of adequate conservative treatment. The American College of Radiology has established Appropriateness Criteria for ordering knee MRI.43

Laboratory Examination

When the initial history and physical examination suggest but do not confirm a specific diagnosis, laboratory examination can play a confirmatory or diagnostic role. This workup could include serology for suspected inflammatory conditions (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein and complete blood count when infection is suspected), autoimmune conditions (rheumatoid factor or auto-antibodies [antineutrophil antibodies]), or microscopic examination of arthrocentesis fluid for gouty crystals or evidence of bacterial infection.3,27,34,44

The authors thank Ms. Rhonda Allard, who was invaluable during the literature search.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using Clinical Queries and the search terms knee pain, evaluation, history, examination, radiographic imaging, laboratory, diagnosis, effusion, gout, and pseudogout. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Evidence, the Cochrane database, Google Scholar, the National Guideline Clearinghouse database, the TRIP database, and UpToDate. Search dates: July, October, and November 2017; July 2018.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Air Force Medical Service, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the U.S. Air Force at large.