Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(5):301-309

Patient information: See related handout on gas, bloating, and belching, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Gas, bloating, and belching are associated with a variety of conditions but are most commonly caused by functional gastrointestinal disorders. These disorders are characterized by disordered motility and visceral hypersensitivity that are often worsened by psychological distress. An organized approach to the evaluation of symptoms fosters trusting therapeutic relationships. Patients can be reliably diagnosed without exhaustive testing and can be classified as having gastric bloating, small bowel bloating, bloating with constipation, or belching disorders. Functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic idiopathic constipation are the most common causes of these disorders. For presumed functional dyspepsia, noninvasive testing for Helicobacter pylori and eradication of confirmed infection (i.e., test and treat) are more cost-effective than endoscopy. Patients with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome should be tested for celiac disease. Patients with chronic constipation should have a rectal examination to evaluate for dyssynergic defecation. Empiric therapy is a reasonable initial approach to functional gastrointestinal disorders, including acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors for functional dyspepsia, antispasmodics for irritable bowel syndrome, and osmotic laxatives and increased fiber for chronic idiopathic constipation. Nonceliac sensitivities to gluten and other food components are increasingly recognized, but highly restrictive exclusion diets have insufficient evidence to support their routine use except in confirmed celiac disease.

Patients with symptoms of gas, bloating, and belching often consult family physicians, particularly when milder chronic symptoms of abdominal pain or altered bowel habits acutely flare up and become less tolerable. Most often, these symptoms are attributable to one or more of the functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), including functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and chronic idiopathic constipation.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional dyspepsia, IBS, and chronic idiopathic constipation can be diagnosed using symptom-based clinical criteria. | C | 2, 3, 7–9, 16 | Excluding organic disease through exhaustive investigation is not necessary; usually only limited testing is needed. |

| Noninvasive testing for Helicobacter pylori, and eradication therapy if positive (test-and-treat strategy), should be used for the initial evaluation of dyspepsia without alarm symptoms in younger patients. | C | 7, 8, 19 | See Table 1 for a list of alarm symptoms; urea breath testing is preferred (Table 4); endoscopy is recommended as the initial test in patients older than 55 years (Table 4). |

| Part of the initial evaluation of patients with diarrhea-predominant or mixed-presentation IBS symptoms should include testing for celiac disease. | C | 9, 20, 21 | If the incidence of celiac disease is known to be less than 1%, testing can be deferred. |

| Empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy is moderately effective for treating functional dyspepsia in patients who are H. pylori negative or who remain symptomatic after H. pylori eradication. | C | 8 | Patients with functional dyspepsia may have increased acid sensitivity. |

| Highly restrictive gluten-free diets and diets restricted in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols have insufficient evidence to be routinely recommended for IBS management. | C | 16, 32, 35 | Questions remain about safety, effectiveness, cost, and practicality of long-term implementation. |

Classified primarily in terms of symptoms, FGIDs are separated into discrete syndromes and are diagnosed by specific criteria. In clinical practice, many patients may not meet all criteria or may have symptoms with significant overlap among syndromes.1 The FGIDs are not diagnoses of exclusion; certain clinical features may require limited testing to exclude other conditions, but exhaustive testing is not necessary before making a diagnosis.2,3

Definitions and Pathophysiology

The FGIDs are characterized as disorders of gut-brain interaction.2 Symptoms, including bloating and abdominal distention, are thought to result from disturbances in intestinal transit and motility, gut microflora, immune function, gas production, visceral hypersensitivity, and central nervous system processing.

Bloating is a sense of gassiness or of being distended, with or without a visible increase in abdominal girth. Bloating is primarily a sensory phenomenon in the small intestine; patients experiencing bloating usually do not produce excess gas but may have lower pain thresholds and increased sensitivity.4

Belching is the expulsion of excess gas from the stomach; it may or may not coexist with bloating and distention. Belching occurs because of an excess of swallowed air and is caused by processes often unrelated to those causing bloating.4

Flatulence is the expulsion of excess colonic gas and is usually related to diet.4 The colon is relatively insensitive to increased gas and distention; excess flatulence does not usually cause symptoms of bloating.

Coexisting anxiety and depression may increase the severity of symptoms of FGIDs, and stressful life events or illness may be related to acute flare-ups; however, these conditions do not specifically cause FGIDs.2

Evaluation

Acute flare-ups or psychological distress related to uncontrolled symptoms may lead patients to seek urgent medical evaluation. A framework for categorizing symptoms and a structured approach to evaluation, particularly when the patient and physician may be new to one another, help to establish an effective relationship.

ESTABLISHING A TRUSTING RELATIONSHIP

A trusting therapeutic relationship is essential for patients to understand and accept the biopsychosocial model of FGIDs, to be confident that the evaluation for other conditions has been adequate, to accept the limitations of therapy and incremental improvements of symptoms, and to engage in effective self-management.2,5

Patients often believe that their symptoms are not appreciated2 because FGIDs are often perceived as less legitimate than structural conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease or infections. Listening carefully and acknowledging patients' symptoms are essential. Patients should be asked about chronicity, waxing and waning of symptoms, temporal relationships, precipitating or aggravating events, recent illness, and psychosocial stressors.

ALARM SYMPTOMS

| Abdominal mass |

| Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) |

| Extreme diarrhea symptoms (large volume, bloody, nocturnal, progressive pain, does not improve with fasting) |

| Fever |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding (melena or hematochezia) |

| Jaundice |

| Lymphadenopathy |

| New-onset symptoms in patients 55 years and older* |

| Odynophagia (painful swallowing) |

| Symptoms of chronic pancreatitis† |

| Symptoms of gastrointestinal cancer, including family history‡ |

| Symptoms of ovarian cancer, including family history§ |

| Tenesmus (rectal pain or feeling of incomplete evacuation) |

| Unintentional weight loss |

| Vomiting |

DIETARY HISTORY

| Possible causes of functional gastrointestinal disorders | Dietary choices | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Artificial sweeteners | Sugar-free gum (especially gum containing sorbitol or mannitol) | Bloating, often with diarrhea |

| Caffeinated beverages | Coffee, soda | Can cause belching and diarrhea but less likely to cause bloating |

| Can decrease lower esophageal sphincter pressure, which causes belching | ||

| Carbonated drinks | Soda, other carbonated beverages | Excess gas and bloating |

| Eating habits | Bolting or gulping food, eating quickly, not thoroughly chewing food, routinely chewing gum | Belching, bloating, gas |

| Over-the-counter medications | Antacids containing magnesium | Diarrhea (bloating less likely) |

| Size and timing of meals | Large or frequent meals, meals eaten late in the day | Bloating with distention, dyspepsia |

| Specific foods | Beans, fiber, fructans, fructose, lactose, legumes | Gas |

CATEGORIZE SYMPTOMS

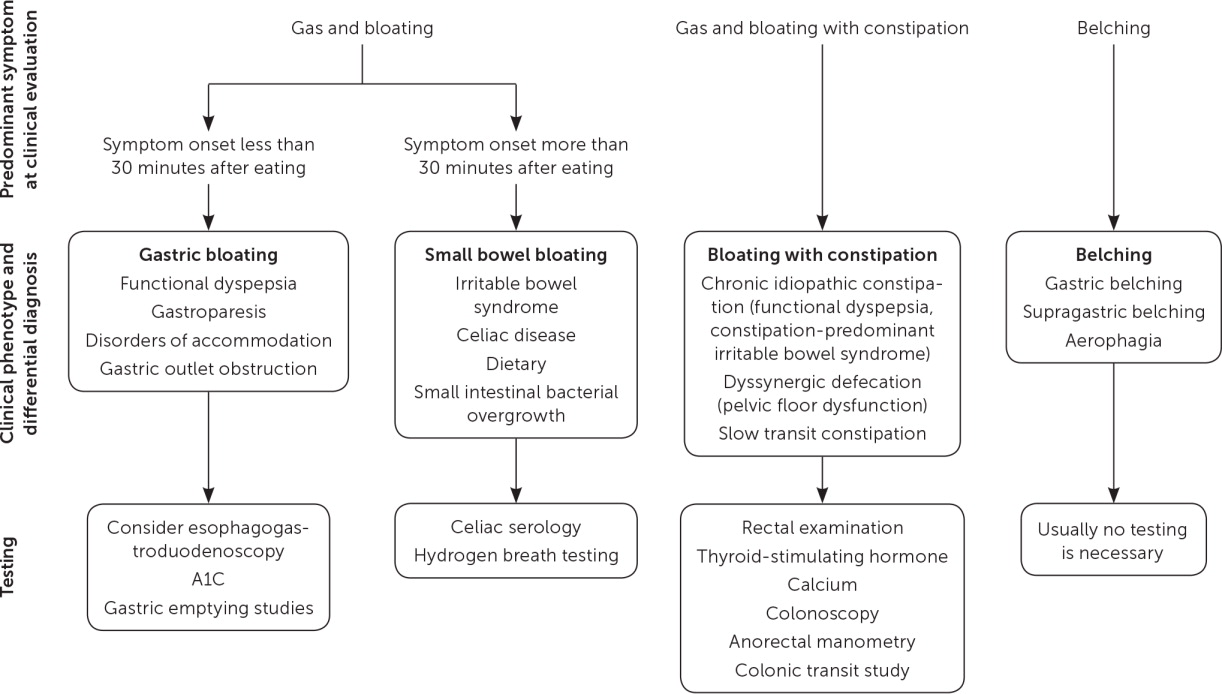

Symptoms can be categorized as representing gastric bloating, small bowel bloating, bloating with constipation, or belching (Figure 113). Two particularly useful questions help localize which distinct level of the gastrointestinal tract is involved: Can you eat a full plate of food? Do you regularly have a good bowel movement?

EXAMINATION

| Patient lying on left side Inspect for anal fissure, external hemorrhoids, or other perineal abnormalities. Check perineal sensation and anocutaneous reflex (“anal wink”) using a cotton swab. |

| Patient bearing down, simulating defecation The perineum should relax and descend 1 to 3.5 cm; a minimal descent or paradoxical perineal rise suggests an inability to relax the pelvic floor muscles during defecation; an exaggerated descent suggests perineal laxity (e.g., childbirth, excessive straining attributable to chronic constipation). The anal sphincter should relax; paradoxical anal sphincter contraction suggests elevated sphincter pressure and anal stricture. Perineal “ballooning,” rectal prolapse, and prolapse of internal hemorrhoids are abnormal findings. Palpate the abdominal wall; excessive contraction suggests the Valsalva maneuver during defecation and ineffective effort. |

| Digital rectal examination while patient is relaxed Assess for increased anal sphincter tone, which may contribute to difficulty with evacuation. Palpate for anal fissure, tenderness, mass, stricture, rectocele, and hard stool. |

| Digital rectal examination while patient is instructed to try to expel finger Internal sphincter and puborectalis muscle should be felt to relax; tightening or lack of perineal descent suggests pelvic floor dyssynergia. Rectal propulsive force should be sufficient to expel finger. |

| Patient squatting, simulating defecation Rectal prolapse may not always be evident with the patient lying on his or her side, even when bearing down. |

TESTING

| Suspected diagnosis | Testing to consider | Clinical features of patient |

|---|---|---|

| Gastric bloating | ||

| Functional dyspepsia | Helicobacter pylori testing (urea breath testing most cost-effective relative to endoscopy; stool antigen testing is less expensive and also a reasonable option; serologic tests are least accurate)7,8,19 | If younger than 55 years with no alarm symptoms, test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori detection and eradication is safe and cost-effective8 |

| EGD | If 55 years or older or with alarm symptoms (Table 1), EGD is indicated | |

| Disorders of accommodation | Gastric accommodation study (only available at specialized centers) | Diagnosis is difficult, and treatments are only minimally effective |

| Testing is of limited utility | ||

| Gastroparesis | Gastric emptying study8 (recommended only if gastroparesis is strongly suspected; should not be routinely obtained in functional dyspepsia) | If diabetes mellitus or recent viral illness and negative EGD, consider gastroparesis |

| Gastric outlet obstruction | EGD | If early satiety or vomiting, or if suspected or known history of peptic ulcer disease, rule out gastric outlet obstruction with EGD |

| Small bowel bloating | ||

| IBS | Celiac serology | Consider testing for celiac disease in patients with diarrhea-predominant or mixed-presentation IBS, or if local prevalence of celiac disease > 10%20,21 |

| Colonoscopy | If 55 years or older, alarm symptoms (Table 1), or routine screening is due, colonoscopy indicated16 | |

| Celiac disease | Celiac serology* | Intestinal symptoms of celiac disease (diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal bloating and distention, gas) are less common than extraintestinal symptoms (anemia, dermatitis herpetiformis, oral lesions, osteoporosis/osteopenia)22 |

| Must include tissue transglutaminase and total IgA (to rule out IgA deficiency) | ||

| If IgA deficiency is present, test with deamidated gliadin | ||

| Serologic testing should ideally be confirmed by biopsy | ||

| SIBO | Lactulose hydrogen breath testing (appropriate only for patients with risk factors for SIBO) | Risk factors for SIBO: structural abnormalities (small bowel diverticula, strictures, surgical blind loops, ileocecal valve resection); disordered motility (scleroderma, type 1 diabetes, use of opioids); acid suppression (chronic proton pump inhibitor use, achlorhydria, gastric resection)4 |

| Functional abdominal distention | Testing usually not necessary | Subjective symptoms of recurrent abdominal pressure with objective increases in abdominal girth |

| More likely related to abdominal wall muscle relaxation than to retained gas9 | ||

| Functional abdominal bloating | Testing usually not necessary | Subjective symptoms of recurrent abdominal pressure, sensation of trapped gas |

| Typically worsens throughout day and after meals, improves overnight9 | ||

| Bloating with constipation | ||

| Chronic idiopathic constipation (functional constipation, constipation-predominant IBS) | Rule out dyssynergic defecation (see example in this table) and secondary constipation | Incomplete evacuation |

| Straining with defecation | ||

| Manual removal of stool | ||

| History of sexual or physical abuse6,15,16 | ||

| Secondary constipation | Hypothyroidism, diabetic neuropathy, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, and hypercalcemia | Inquire about medications (calcium-containing antacids, iron supplements, anticholinergics, opioids) |

| Dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction) | Careful perineal and rectal examination (often sufficient to guide further testing) | Incomplete evacuation |

| Anorectal manometry (may be required to justify insurance coverage of treatment) | Straining with defecation | |

| Manual removal of stool | ||

| History of sexual or physical abuse6,15,16 | ||

| Slow transit constipation | Colonic transit study (consider only after ruling out dyssynergic defecation) | Rare condition |

| False-positive results not uncommon | ||

| Belching | ||

| Gastric belching | Testing usually not necessary but can be reliably diagnosed by manometry and impedance testing7 | Rapid eating and gum chewing, which may cause excessive air swallowing; lower esophageal sphincter relaxes with belching7 |

| Supragastric belching | Testing usually not necessary but can be reliably diagnosed by manometry and impedance testing7 | Patients who are belching during conversation; worse when discussing symptoms and better when distracted; lower esophageal sphincter does not relax with belching7 |

| Aerophagia (“air swallowing”—now considered a historical term)† | Testing not necessary | Anxiety, rapid eating, and chewing gum may cause excessive air swallowing, both supragastric and gastric (see above)23 |

Gastric Bloating

Symptoms occurring within 30 minutes after eating or the inability to finish a meal are attributable to upper gastrointestinal disorders, usually functional dyspepsia. Other conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Helicobacter pylori infection, gastroparesis, impaired gastric accommodation, and gastric outlet obstruction, must also be considered, although definitive testing may be deferred in favor of empiric treatment.

FUNCTIONAL DYSPEPSIA

Patients with functional (nonulcer) dyspepsia typically report postprandial fullness, bloating, or early satiation; however, some patients with functional dyspepsia may instead report epigastric pain or burning unrelated to meals.7,8 In addition, some patients with GERD may report symptoms that also occur in patients with functional dyspepsia, including nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and belching. This suggests that functional dyspepsia and GERD may coexist in some patients or that others thought to have GERD may instead have functional dyspepsia.25

The relationship between functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection is unclear. H. pylori eradication results in functional dyspepsia symptom resolution in some patients. Consequently, a test-and-treat strategy (noninvasive testing for H. pylori [e.g., urea breath testing] and treatment of confirmed infection) is recommended rather than expensive and invasive tests, such as endoscopy8,19 (Table 44,6–9,15,16,19–24).

The relationship between functional dyspepsia and acid secretion is also unclear; empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy reduces functional dyspepsia symptoms in some patients, even when acid reflux cannot be demonstrated. Therefore, a trial of antisecretory therapy is recommended for patients who are H. pylori negative or for those who remain symptomatic after H. pylori eradication8,25 (eTable A).

| Intestinal lumen |

| Diet General dietary guidance: Eat in moderation; get adequate but not excessive fiber; decrease consumption of fatty and spicy foods; avoid caffeine, soft drinks, carbonation, and artificial sweeteners.A1,A2 Restricted diet: Diets restricted in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols may improve IBS symptoms in some patients, but questions remain regarding their long-term safety, effectiveness, and practicality.A3,A4 Gluten-free diet: The long-term effects of gluten-free diets on the microbiome and general nutrition are uncertain; they may lead to increased fat and sugar consumption. Strict gluten-free diets are expensive and difficult to follow and should be advised only for patients with proven celiac disease.A1,A5–A7 |

| Probiotics Probiotics, especially Bifidobacterium infantis, improve bloating, gas, and pain in IBS and may also help chronic idiopathic constipation.A1,A8 |

| Exercise Regular daily exercise decreases symptoms of IBS and chronic idiopathic constipation.A1 |

| Fiber Soluble fiber (psyllium; 25 to 30 g daily) provides a small benefit for some patients with IBS,A1,A8,A9 but it can also worsen bloating. Insoluble fiber (bran, methylcellulose, calcium polycarbophil; two heaped teaspoons daily) is somewhat more effective for chronic idiopathic constipation than soluble fiber, but it can worsen bloating and flatulence in many patients.A8 Increase fiber gradually to minimize bloating, distention, flatulence, and cramping.A1,A8,A9 Worsening of gas and bloating suggests underlying dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction).A9 |

| Osmotic laxatives Polyethylene glycol (Miralax; 17 g once daily) is the osmotic laxative best studied and most effective for chronic idiopathic constipation.A8,A10 Other osmotic laxatives include lactulose, sorbitol, and mannitol. |

| Proton pump inhibitors Proton pump inhibitors are recommended as empiric therapy in patients with functional dyspepsia who are Helicobacter pylori negative or who remain symptomatic after H. pylori eradication.A11,A12 |

| Bowel wall |

| Opioid agonists Loperamide (2 to 4 mg up to four times daily) decreases colonic transit and increases water absorption, improving many symptoms of diarrhea-predominant IBS.A8 Diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil) has not been studied in IBS.A8 |

| Antispasmodics Hyoscyamine (Levsin; 0.125 to 0.25 mg three times daily, 30 minutes before meals) is moderately effective for IBS.A9 Hyoscyamine, extended release (Levbid; 0.375 to 0.75 mg two times daily; maximum of 1.5 mg daily) is moderately effective for IBS.A9 Dicyclomine (20 mg four times daily, may increase to a maximum of 40 mg four times daily, 30 minutes before meals) is moderately effective for IBS.A9 Peppermint oil (200 to 750 mg two to three times dailyA8) is moderately effective for IBS.A9 |

| Stimulant laxative Stimulant laxatives (bisacodyl, cascara, senna) increase motility in chronic idiopathic constipation but may cause pain and diarrheaA8,A13,A14; they are usually reserved for patients with dysmotility disorders or opioid-induced constipation. |

| Prokinetic agents Buspirone (Buspar; 5 to 10 mg three times daily, 30 minutes before meals), in addition to its antidepressant benefit, relaxes the gastric fundus and is effective for symptoms of functional dyspepsia.A15 Metoclopramide (Reglan), although approved for gastroparesis, has not been well studied in functional dyspepsia. Irreversible tardive dyskinesia can occur even at low dosages. It should not be used routinely for functional dyspepsia symptoms but may be considered after test-and-treat therapy, proton pump inhibitor therapy, and tricyclic antidepressant therapy.A11,A16 |

| Neuromodulatory gut-brain axis |

| Tricyclic antidepressants Amitriptyline (10 to 50 mg at bedtime; increase by 10 mg every one to two weeks) and other tricyclic antidepressants are moderately effective for symptom relief in diarrhea-predominant IBS and functional dyspepsia (histaminergic properties are moderately sedating; anticholinergic properties are moderately constipating).A10,A11,A17,A18 |

| Central nervous system |

| Psychotropic drugs (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors) treat symptoms of underlying anxiety or depression but are less effective for associated pain and bloating.A17,A18 Psychological therapies (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy, hypnotherapy) improve quality of life and overall function in IBS and functional dyspepsia but are less effective for associated pain and bloating.A17,A18 |

GASTROPARESIS

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder of delayed gastric emptying unrelated to mechanical obstruction. Most patients with gastroparesis experience nausea and vomiting in addition to dyspeptic symptoms. Idiopathic gastroparesis is most common in young or middle-aged women and sometimes develops after viral gastroenteritis; resolution of the disorder may take a year or more.26 Diabetic gastroparesis is a relatively rare complication (occurring in only 1% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus)27 closely related to the degree of hyperglycemia; improved glycemic control often results in improved symptoms. 28 Bariatric surgery or fundoplication may occasionally cause postsurgical gastroparesis.26

IMPAIRED GASTRIC ACCOMMODATION

Reduced gastric accommodation, a disorder of the vagally mediated reflex that permits the stomach to adapt to food as it enters, has been recognized as distinct from delayed gastric emptying, but its exact role in dyspeptic symptoms is unclear. Testing is done only in specialized centers, and no specific treatments exist.29

GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

Gastric outlet obstruction may also cause bloating. Most gastric outlet obstruction is attributable to chronic peptic ulcer disease and scarring; in patients without alarm symptoms (Table 14,6–12), the risk of malignancy is low. Eradication of H. pylori infection often results in long-term improvement of gastric outlet obstruction.19,30

Small Bowel Bloating

Symptoms, including abdominal distention, occurring more than 30 minutes after eating originate in the small bowel and proximal colon. IBS is the most common cause of small bowel bloating, but celiac disease should be excluded. Nonceliac food sensitivities and other conditions must also be considered. Functional abdominal bloating and functional abdominal distention are characterized by subjective symptoms of abdominal pressure, with or without objective increases in abdominal girth; they are more likely related to abdominal wall muscle relaxation than to retained gas9 (Table 44,6–9,15,16,19–24).

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

IBS is characterized by pain, usually with bloating or abdominal distention, and associated with disordered bowel habits. Subtypes of IBS depend on the predominant bowel habit: diarrhea (IBS-D), constipation (IBS-C), or mixed (IBS-M).9,10,16 Fiber, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil are moderately effective for IBS symptoms in some patients16,31 (eTable A).

CELIAC DISEASE

Celiac disease may present with bloating, flatulence, diarrhea or constipation, weight loss, anemia attributable to malabsorption of iron or folic acid, or osteoporosis attributable to calcium malabsorption. If serologic testing is positive, duodenal biopsy should be performed. False-negative results may occur in serologic testing if the patient has already been on a gluten-free diet (Table 44,6–9,15,16,19–24). Strict gluten-free diets are expensive and difficult to follow and should be advised only for patients with proven celiac disease.20,21

FOOD SENSITIVITIES

In addition to malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease or lactase deficiency, various foods can also induce or exacerbate symptoms in patients with various FGIDs, particularly IBS. Strict elimination diets are usually not necessary, but restriction of identified foods, particularly at times of symptom flare-ups, is often helpful.

Gluten. The clinical entity currently referred to as nonceliac gluten sensitivity is incompletely understood but seems to closely overlap with other FGIDs.32

Lactose. IBS may be exacerbated by milk or other dairy products, and lactose intolerance attributable to lactase deficiency may mimic the symptoms of IBS. In addition, at least 25% of patients with FGIDs also have lactase deficiency. Lactose intolerance may be diagnosed using hydrogen breath testing, but this is not always accurate in patients with FGIDs; careful monitoring of symptoms in relation to ingestion of dairy products may be equally helpful33 (Table 44,6–9,15,16,19–24).

FODMAPs. Foods containing a variety of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) may precipitate symptoms in certain individuals (Table 54,34). Some patients find that avoiding certain FODMAP-containing foods may reduce IBS symptoms, but the routine use of highly restrictive exclusion diets has not been well studied and is not recommended.35

| Oligosaccharides (fructans) | Wheat (large amounts), rye (large amounts), onions, leeks, zucchini |

| Disaccharides (lactose) | Dairy products, cheese, milk, yogurt |

| Monosaccharides (excess fructose) | Honey, apples, pears, peaches, mangoes, fruit juice, dried fruit |

| Polyols (sorbitol) | Apricots, peaches, artificial sweeteners, sugar-free gums |

| Galactose (raffinose) | Lentils, cabbage, brussels sprouts, asparagus, green beans, legumes |

SMALL INTESTINAL BACTERIAL OVERGROWTH

Constipation with Bloating

Patients with difficult, infrequent, or incomplete bowel movements, usually with lower but sometimes with upper abdominal pain, typically have either IBS-C or functional constipation; dyssynergic defecation related to pelvic floor dysfunction, as well as secondary causes, must also be considered.9,16

CHRONIC IDIOPATHIC CONSTIPATION

Chronic idiopathic constipation includes IBS-C (predominantly pain) and functional constipation (predominantly constipation), both of which are probably part of the same condition. The term “normal transit constipation” also refers to functional constipation. Stool transit is normal, but bowel movements are considered unsatisfactory. Symptoms often worsen with psychosocial stress and usually respond to fiber supplementation or osmotic laxatives.6,15,16

DYSSYNERGIC DEFECATION

Dyssynergic defecation, caused by poor coordination of the pelvic floor, anal sphincter, and abdominal wall muscles during attempted defecation, results in prolonged or excessive straining even with relatively soft stools.9 Rectal examination is important17 (Table 36,15–17) to guide further testing (Table 44,6–9,15,16,19–24). Structured biofeedback-aided pelvic floor retraining is often successful.6,15

SLOW TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

Truly prolonged colonic transit times are relatively rare. Dyssynergic defecation can appear to affect colonic transit, so this condition must be excluded before considering a diagnosis of slow transit constipation. Symptoms tend not to respond to fiber or laxatives, although biofeedback has been reported to be effective in one trial.6,15

SECONDARY CONSTIPATION

Belching

Belching prevents gas accumulation and distention. Typically occurring 25 to 30 times daily, it is usually not perceived and is rarely excessive or troublesome.

SUPRAGASTRIC BELCHING

Troublesome, repetitive belching, sometimes occurring up to 20 times per minute, is an involuntary but learned behavior, often in response to stress, anxiety, or unpleasant gastrointestinal symptoms. Air is sucked into the esophagus and immediately expelled without ever reaching the stomach.36 Symptoms worsen while they are being discussed and abate with distraction and sleep.37 Treatment of the underlying anxiety, as well as biofeedback, may be helpful.38

GASTRIC BELCHING

Initial Treatment

Treatment of FGIDs begins with reassurance about the generally benign course of these conditions. The concept of the biopsychosocial model should be introduced as appropriate; it is important to stress that although anxiety, depression, and psychosocial stressors do not cause FGIDs, they can worsen symptoms and should be addressed if present.

Self-managed combinations of medications and dietary interventions are most effective. Several safe and inexpensive drugs are available, often over the counter (eTable A); newer agents are generally more appropriate for patients with complicated or intractable symptoms.2,31 Most patients will have incremental improvement over time with occasional flare-ups; approximately 50% of patients will have resolution of symptoms, 30% will have fluctuating symptoms, and 20% will develop new symptoms.40

Data Sources: We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the search terms gas, bloating, belching, functional gastrointestinal disorders, FGID, IBS, functional dyspepsia, constipation, celiac disease, FODMAP, and gluten-free, alone and in combination with one another. We examined clinical trials, meta-analyses, review articles, and clinical guidelines, as well as the bibliographies of selected articles. Cochrane and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: June through October 2018.