Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(1):39-48

Patient information: See related handout on amenorrhea.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Menstrual patterns can be an indicator of overall health and self-perception of well-being. Primary amenorrhea, defined as the lifelong absence of menses, requires evaluation if menarche has not occurred by 15 years of age or three years post-thelarche. Secondary amenorrhea is characterized by cessation of previously regular menses for three months or previously irregular menses for six months and warrants evaluation. Clinicians may consider etiologies of amenorrhea categorically as outflow tract abnormalities, primary ovarian insufficiency, hypothalamic or pituitary disorders, other endocrine gland disorders, sequelae of chronic disease, physiologic, or induced. The history should include menstrual onset and patterns, eating and exercise habits, presence of psychosocial stressors, body weight changes, medication use, galactorrhea, and chronic illness. Additional questions may target neurologic, vasomotor, hyperandrogenic, or thyroid-related symptoms. The physical examination should identify anthropometric and pubertal development trends. All patients should be offered a pregnancy test and assessment of serum follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. Additional testing, including karyotyping, serum androgen evaluation, and pelvic or brain imaging, should be individualized. Patients with primary ovarian insufficiency can maintain unpredictable ovary function and may require hormone replacement therapy, contraception, or infertility services. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea may indicate disordered eating and low bone density. Treatment should address the underlying cause. Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome should undergo screening and intervention to attenuate metabolic disease and endometrial cancer risk. Amenorrhea can be associated with clinically challenging pathology and may require lifelong treatment. Patients will benefit from ample time with the clinician, sensitivity, and emotional support.

Menstrual patterns can be an indicator of overall health status and self-perception of well-being.1,2 A broad differential is important to avoid missing rare or emergent pathology because many underlying conditions can present as amenorrhea.3 Primary amenorrhea is the lifelong absence of menses.3 Evaluation should be considered if menarche has not occurred by 15 years of age or three years post-thelarche.1,4 Lack of any pubertal development by 13 years of age should prompt investigation for delayed puberty.4,5

Secondary amenorrhea is the cessation of previously regular menses for three months or previously irregular menses for six months and warrants evaluation.1,3,6 Oligomenorrhea, the lack of menstruation for intervals longer than 35 days in adults or 45 days in adolescents, is approached similarly.1,3,6–8

Clinicians should offer a safe and welcoming environment where patients feel comfortable discussing reproductive health concerns by establishing confidentiality, building rapport, and allotting the requisite time needed to talk about possible long-term treatments and sequelae of chronic medical conditions. Preventive health visits should include menstrual cycle education, such as measurement from the first day of menstruation to the first day of the next cycle; intervals are typically 21 to 34 days.1 Smart phone apps (e.g., Clue) are useful for determining patterns.9

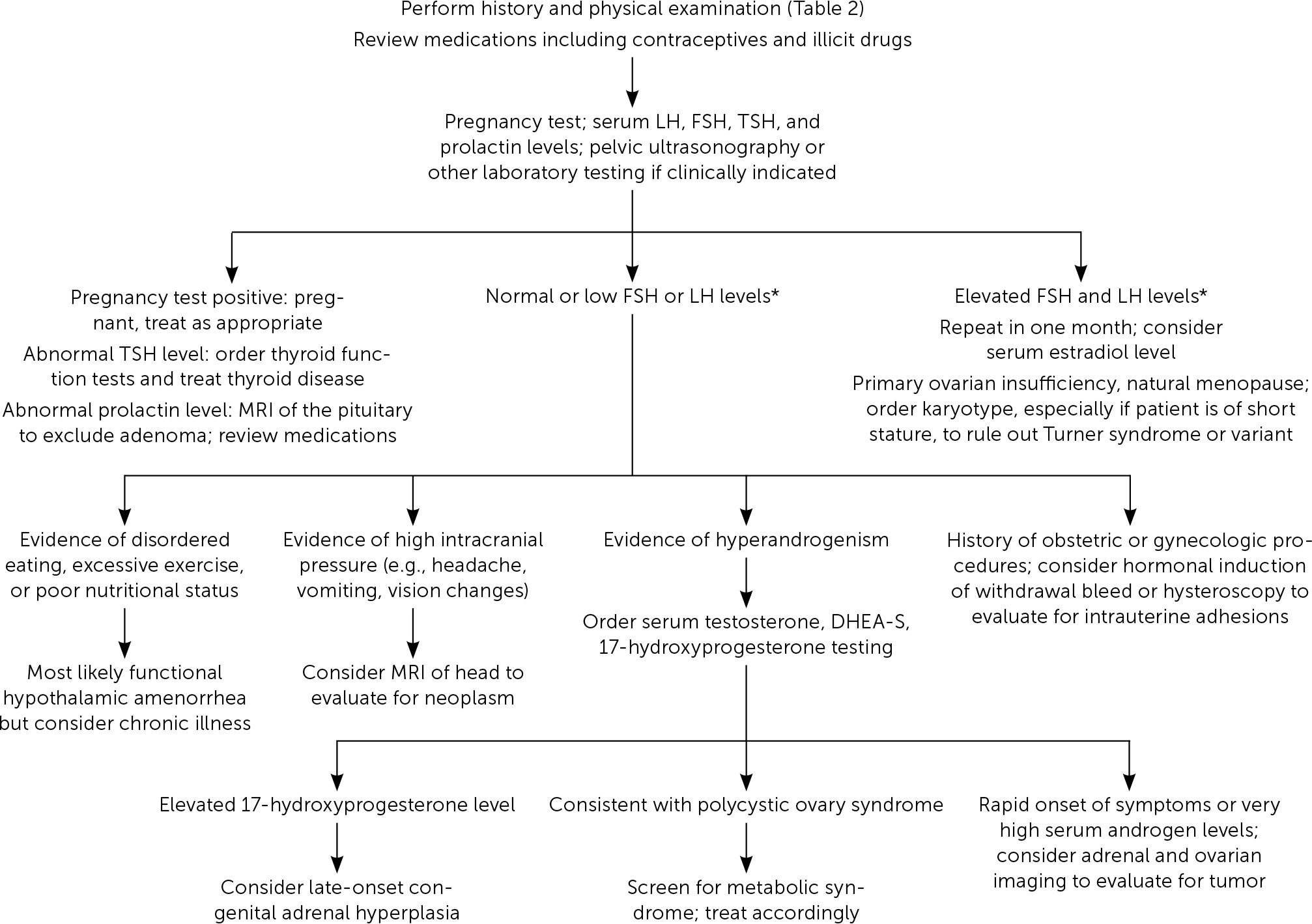

Etiologies of amenorrhea can be categorized as: outflow tract abnormalities, primary ovarian insufficiency, hypothalamic or pituitary disorders, other endocrine gland disorders, sequelae of chronic disease, physiologic, or induced3,6 (Table 11–3,5,6,10–12). Abnormal pelvic anatomy is important to consider in the evaluation of primary amenorrhea.3 All causes of secondary amenorrhea may present as primary amenorrhea and the evaluation is similar (Figure 1 and Figure 2).3

| Outflow tract abnormalities Acquired

Congenital

Primary ovarian insufficiency Acquired

Congenital

Hypothalamic or pituitary disorders Autoimmune disease Brain radiation | Hypothalamic or pituitary disorders(continued) Constitutional delay of puberty Empty sella syndrome Functional (overall energy deficit or stress)

Gonadotropin deficiency (e.g., Kallmann syndrome) Hyperprolactinemia

Infarction (e.g., Sheehan syndrome) Infiltrative disease (e.g., sarcoidosis) Infection (e.g., meningitis, tuberculosis) Medications or illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine) Trauma or surgery Tumor (primary or metastatic) | Other endocrine gland disorders Adrenal insufficiency Androgen-secreting tumor (e.g., ovarian or adrenal) Cushing syndrome Diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled Late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia Polycystic ovary syndrome (multifactorial) Thyroid disease Amenorrhea attributed to chronic disease Celiac disease Inflammatory bowel disease Other chronic disease Physiologic or induced Breastfeeding Contraception Exogenous androgens Menopause Pregnancy |

Evaluation

HISTORY

A detailed history should include menstrual patterns (if any), pregnancy and breastfeeding history, eating and exercise habits, psychosocial stressors (e.g., perfectionist behaviors), changes in body weight, fractures, medication or substance use, chronic illness, and timing of breast and pubic hair development2,3,6 (Table 21–3,5,6,10–12). Galactorrhea, headaches, or visual field defects can indicate hypothalamic or pituitary disease,13,14 and acne or hirsutism can indicate hyperandrogenism.15 Vasomotor symptoms such as hot flashes or night sweats may indicate primary ovarian insufficiency.10 A family history should include the age of menarche of relatives and any chronic disease history.2,3

| Findings | Associations |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Chemotherapy or radiation | Impairment of specific organ or structure, (e.g., brain, pituitary, ovary) |

| Family history of early or delayed menarche | Constitutional delay of puberty |

| Galactorrhea | Pituitary tumor |

| Hirsutism, acne | Hyperandrogenism, PCOS, ovarian or adrenal tumor, CAH, Cushing syndrome |

| Illicit or prescription drug useLoss of smell (anosmia) | Multiple associations, consider effect on prolactin |

| Loss of smell (anosmia) | Kallman syndrome (GnRH deficiency) |

| Menarche and menstrual history | Primary vs. secondary amenorrhea |

| Sexual activity | Pregnancy |

| Significant headaches or vision changes | Central nervous system tumor, empty sella syndrome |

| Temperature intolerance, palpitations, diarrhea, constipation, tremor, depression, skin changes | Thyroid disease |

| Vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hot flashes or night sweats) | Primary ovarian insufficiency, natural menopause |

| Weight loss, excessive exercise, poor nutrition, psychosocial distress, diets | Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea |

| Physical examination | |

| Abnormal thyroid examination | Thyroid disorder |

| Acanthosis nigricans or skin tags | Hyperinsulinemia (PCOS) |

| Anthropomorphic measurements; growth charts | Multiple associations; Turner syndrome, constitutional delay of puberty |

| Body mass index | High: PCOS Low: Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea |

| Bradycardia | Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (e.g., anorexia nervosa) |

| Breast development (normal progression) | Presence of circulating estrogen* |

| Dysmorphic features (e.g., webbed neck, short stature, low hairline) | Turner syndrome |

| Male pattern baldness, increased facial hair, acne | Hyperandrogenism, PCOS, ovarian or adrenal tumor, CAH, Cushing syndrome |

| Pelvic examination | |

| Absence or abnormalities of cervix or uterus | Rare congenital causes including Müllerian agenesis or androgen insensitivity syndrome |

| Clitoromegaly | Androgen-secreting tumor; CAH; 5α-reductase deficiency |

| Presence of transverse septum or imperforate hymen | Outflow tract obstruction |

| Reddened or thin vaginal mucosa | Decreased endogenous estrogen |

| Sexual maturity rating abnormal | Turner syndrome, constitutional delay of puberty, rare causes |

| Striae, buffalo hump, central obesity, hypertension | Cushing syndrome |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Clinicians should review trends in height, weight, and body mass index.2,3 Normal breast development indicates the presence of circulating estrogen.6 Atrophic vaginal mucosae suggests low estrogen, and a shortened vagina may indicate outflow tract obstruction or Müllerian agenesis.6,16,17 Signs of virilization suggest hyperandrogenic conditions. Evidence of dysmorphism may suggest a congenital syndrome.6,10,17

LABORATORY AND OTHER TESTING

In all cases, pregnancy should be excluded with a pregnancy test.2,3,6 Serum patterns of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone identify most endocrine causes of amenorrhea2,3,6,10–12 (Figure 13). Serum free and total testosterone, and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels may be obtained if there is evidence of hyperandrogenism8,15,18,19 (Table 32,5,6,10–12). A 17-hydroxyprogesterone level collected at 8 a.m. assesses for late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia.2,15 Low anti-Müllerian hormone correlates with ovarian reserve and may indicate primary ovarian insufficiency or menopause (Table 4).2

| Findings | Associations |

|---|---|

| Laboratory testing (refer to local reference values) | |

| 17-hydroxyprogesterone level (collected at 8 a.m.) | High: late-onset CAH |

| Anti-Müllerian hormone | High: Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea, PCOS Low: Primary ovarian insufficiency |

| Complete blood count and metabolic panel | Abnormal: chronic disease (e.g., elevated liver enzymes in functional hypothalamic amenorrhea) |

| Estradiol | Low: Poor endogenous estrogen production (suggestive of poor current ovarian function) |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone | High: Primary ovarian insufficiency; Turner syndrome Low: Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea Normal: PCOS; intrauterine adhesions; multiple others |

| Free and total testosterone; dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | High: Hyperandrogenism, PCOS, ovarian or adrenal tumor, CAH, Cushing syndrome |

| Karyotype | Abnormal: Turner syndrome, rare chromosomal disorders |

| Pregnancy test | Positive: Pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy |

| Prolactin | High: Pituitary adenoma, medications, hypothyroidism, other neoplasm |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone | High: Hypothyroidism Low: Hyperthyroidism |

| Radiographic testing | |

| Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry | Evaluation of fracture risk |

| MRI of the adrenal glands | Androgen-secreting adrenal tumor |

| MRI of the brain (including sella)* | Tumor (e.g., microadenoma) |

| Pelvic organ ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging | Morphology of pelvic organs, polycystic ovarian morphology, androgen-secreting ovarian tumor |

| 17-OHP | AMH | DHEA-S | Estradiol | LH (IU per L) | LH/FSH | FSH (IU per L) | Prolactin | Testosterone | TSH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | High | Normal | High normal | Low | < 15 | > 1 | < 10 | Normal | High | Normal |

| Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea | Normal | High | Normal | Low | < 10† | ~ 1 | < 10† | Low normal | Low normal | Low normal |

| Hyperprolactinemia | Normal | Normal | Normal or slightly high | Low | < 10 | > 1 | < 10 | High | Normal | High or normal |

| Menopause | Normal | Low | Normal | Low | > 15 | < 1 | > 15 | Normal | Low normal | Normal |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | Normal | Normal or high | High normal | Low | < 15 | > 1 | < 10 | High normal | High or high normal | Normal |

| Primary ovarian insufficiency | Normal | Low | Normal | Low | > 15 | < 1 | > 15 | Normal | Low normal | Normal |

Karyotyping should also be considered in patients of short stature to evaluate for Turner syndrome.6,20 Patients with this syndrome require screening for cardiac and renal defects, neurocognitive and behavior disorders, hypothyroidism, and hearing loss, and generally require hormone therapies for puberty induction and growth, often in consultation with a pediatric endocrinologist.17,20,21

Pelvic ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify abnormal reproductive anatomy or detect an androgen-secreting tumor.2,15 MRI of the brain can identify pituitary and other tumors.2,6,13 Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry can establish baseline fracture risk in patients with concerns for primary ovarian insufficiency or functional hypothalamic amenorrhea.2,22 A hormonal challenge can be used after excluding pregnancy to determine the presence of functioning anatomy; however, the predictive value of this test on adequate endometrial estrogen exposure is inconsistent.3,17,23 A common regimen for a hormonal challenge is 10 mg of medroxyprogesterone (Provera) orally per day for 10 days; withdrawal bleeding may indicate estrogen exposure (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]) and lack of bleeding may indicate a lowestrogen condition.2,24

Differential Diagnosis and Management

OUTFLOW TRACT ABNORMALITIES

Outflow tract abnormalities are generally associated with 46,XX chromosomal patterns and normal pubertal progression. Müllerian agenesis occurs in approximately one in 5,000 females and in 15% of females diagnosed with primary amenorrhea.25,26 It is characterized by the abnormal development of reproductive anatomy and is associated with urologic and skeletal malformations.16,25 Transverse septum and imperforate hymen may present with cyclic pelvic pain. Intrauterine adhesions can occur after endometrial instrumentation and are corrected using hysteroscopy. Cervical stenosis can occur after cervical procedures, radiation, or vaginal birth.6,27

Androgen insensitivity syndrome is characterized by the resistance of peripheral tissues to testosterone in patients with 46,XY chromosomal patterns.28–30 Patients with 5α-reductase deficiency are phenotypic females that develop male secondary sex characteristics at puberty. Both of these rare conditions are confirmed by genetic analysis or enzyme assays.28 Prophylactic gonadectomy may require evaluation by a pediatric urologist based on malignancy risk and patient or guardian preferences.31

PRIMARY OVARIAN INSUFFICIENCY

Primary ovarian insufficiency affects approximately one in 100 females and is defined by follicle dysfunction or depletion.10,17,32 It is diagnosed in patients younger than 40 years with two serum follicle-stimulating hormone levels in the menopausal range obtained at least one month apart.10,17 Vasomotor symptoms and vaginal dryness are common.10,11

Most cases are idiopathic; however, irradiation, chemotherapy, infections, tumors, autoimmune processes, and chromosomal irregularities can also cause primary ovarian insufficiency.10 A karyotype is abnormal in approximately one-third of patients with primary amenorrhea, and it should be offered to all patients with a diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency to identify Turner syndrome (or variants).10,21

Patients diagnosed with primary ovarian insufficiency should be offered testing for FMR1 gene premutation, which confers the risk of fragile X syndrome in children.10,11,33,34 Testing for thyroid and adrenal antibodies and annual or biennial screening for hypothyroidism may be considered given how often these conditions coexist.10,11,35

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may reduce associated vasomotor symptoms, bone mineral density loss, and cardiovascular risk and should be continued until the age of natural menopause (50 to 51 years).3,20,36–39 A common post-pubertal regimen of HRT is 100 mcg of daily transdermal estradiol or 0.625 mg of daily oral conjugated estrogens, adding 200 mg of micronized oral progesterone daily for 12 days each month.3,37,38 Transdermal estrogen may be associated with lower venous thromboembolism risk than oral formulations.40 It is also reasonable to recommend 1,200 mg of calcium daily and 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily with regular weight-bearing exercises to maintain bone mineral density in accordance with guidelines for postmenopausal women.10,41

Approximately 10% of females diagnosed with primary ovarian insufficiency retain fertility.10 HRT may not adequately suppress ovulation; therefore, barrier or intrauterine contraceptives may augment HRT for contraceptive purposes.10,38,42 Combined hormonal contraceptives may be substituted for HRT to adequately prevent pregnancy and provide the noncontraceptive benefits of HRT; this approach requires higher doses of estrogen, which may confer additional venous thromboembolic risk.38,43 A primary ovarian insufficiency diagnosis introduces long-term challenges for patients and families. Clinicians should offer ample time, sensitivity, and emotional support to the patient.11

HYPOTHALAMIC AND PITUITARY CAUSES

Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is a disorder of chronic anovulation caused by suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis from body weight loss, excessive exercise, or stress and may result in infertility or bone density loss.2,44–46 The pathology is similar to the female athlete triad; both are characterized by menstrual dysfunction, low energy availability, and decreased bone mineral density.2,22,46 Although functional hypothalamic amenorrhea is a diagnosis of exclusion, evaluation typically reveals low or low-normal serum-luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels and low serum estradiol.2 Bone mineral density testing should be considered after six months of amenorrhea, severe nutritional deficit, or history of stress fracture.2,22

Treatment should correct the underlying cause to restore ovulatory function through behavior change, nutritional repletion (e.g., caloric intake, vitamin D), stress reduction, and weight gain.2,22,46 A multidisciplinary team including a clinician, nutritionist or registered dietician, and therapist may be optimal.2,22 Patients with severe bradycardia, hypotension, orthostasis, or electrolyte abnormalities may require inpatient treatment.2 A return to play tool to guide recommendations for athletes is provided in eTable A.

| Magnitude of risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Low risk = 0 points each | Moderate risk = 1 point each | High risk = 2 points each |

| Low energy availability with or without an eating disorder | No dietary restriction | Some dietary restriction; current or history of disordered eating | Meets DSM-5 criteria for current or history of an eating disorder |

| Low BMI or expected weight | BMI ≥ 18.5 kg per m2, ≥ 90% expected weight, or weight stable | BMI 17.5 kg per m2 to < 18.5 kg per m2, < 90% expected weight, or 5% to < 10% weight loss per month | BMI ≤ 17.5 kg per m2, < 85% expected weight, or ≥ 10% weight loss per month |

| Delayed menarche | Menarche < 15 years | Menarche 15 to < 16 years | Menarche ≥ 16 years |

| Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea (current or history) | > 9 menses in 12 months | 6 to 9 menses in 12 months | < 6 menses in 12 months |

| Low bone mineral density† | Z-score ≥ −1.0 | Z-score −1.0 to < −2.0, especially in weight-bearing sports | Z-score ≤ −2.0 |

| Stress reaction/fracture | None | 1 | 2 or more, or 1 high-risk fracture (e.g., trabecular site such as femoral neck, sacrum, or pelvis) |

| Cumulative risk | # Points + | # Points + | # Points = Total Score |

Combined oral contraceptives have not been shown to improve bone density; however, after a reasonable trial of nonpharmacologic therapy (i.e., six to 12 months), clinicians may recommend short-term use of transdermal 17β-estradiol (e.g., 100-mcg patch if bone age is 15 years or older) and cyclic oral progestin (e.g., medroxyprogesterone, 2.5 mg daily, 10 days per month) for this purpose as it avoids first-pass liver metabolism.2,46–48 Hormonal contraceptives may mask underlying pathology but should be considered for patients at risk of pregnancy because ovulation may precede menstruation.2 The Endocrine Society recommends against bisphosphonate use in this population.2

Hyperprolactinemia. Elevated serum prolactin may induce amenorrhea by inhibiting gonadotrophs. Common causes include medication use (e.g., antipsychotics), pregnancy, and pituitary adenoma.13,14 Most patients with elevated serum prolactin will require MRI of the pituitary unless prolactin levels collected at least three days after discontinuing inciting medications have normalized.14 The risk of withdrawing medications (e.g., psychosis) may exceed the benefits (e.g., bone health).14 Symptomatic prolactinomas may be treated with dopamine agonists or resection.13,14

Other Central Nervous System Causes. Amenorrhea may be caused by hypothalamic-pituitary axis damage through inflammation, ischemia, infiltration, infection, or trauma. Disorders affecting pubertal development, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency and constitutional delay, have been described previously in American Family Physician.5

OTHER ENDOCRINE CAUSES

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. PCOS is a multifactorial endocrine disorder characterized by ovulatory dysfunction, biochemical or clinical androgen access, and polycystic ovaries.6,8,12,49 The Rotterdam Consensus Criteria require two of the aforementioned features for diagnosis; the Androgen Excess Society requires hyperandrogenism and another feature.8,12,49 Pelvic ultrasonography is not required for diagnosis.8,49,50 Diagnostic accuracy in adolescence is challenging because anovulation and polycystic ovarian morphology can be physiologic; therefore, hyperandrogenism and persistent oligomenorrhea are key to diagnosis.8,49 Benefits of early management may outweigh risks of delay for diagnostic certainty.8,49

Markedly elevated serum androgens could indicate other hyperandrogenic conditions, but strict cut-offs are not defined.2,12,49 PCOS is associated with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. Patients should be screened for hypertension and an elevated body mass index at each visit, and should be screened for dyslipidemia and impaired glucose tolerance (i.e., two-hour oral glucose tolerance testing [preferred] or A1C level) every three to five years.12,49–51

Healthy eating habits and regular exercise should be recommended for all patients with PCOS. Weight loss may restore regular menses and improve metabolic comorbidities in patients with an elevated body mass index.12,49,50 Combined hormonal contraceptives are first-line therapy for menstrual abnormalities, hirsutism, acne, and protection from endometrial cancer caused by unopposed estrogen secretion.12,14,49,50 Metformin may prevent diabetes mellitus and regulate menses, and it may be appropriate for patients with impaired glucose tolerance when lifestyle modification is unsuccessful or for those with contraindications to applicable contraceptives.12,49 Metformin is ineffective for treating acne or hirsutism.15,49 For patients with PCOS and infertility, letrozole (Femara) is a first-line therapeutic option, because it confers higher ovulation, pregnancy, and live birth rates than clomiphene.12,50,52

Thyroid and Adrenal Disease. Hypo- and hyperthyroidism may cause amenorrhea.2,6,12 Late-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia (e.g., 21-hydroxylase deficiency) is a common cause of hyperandrogenic amenorrhea; an elevated serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone level should be followed by confirmatory adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation testing.12,49,53 Adrenal or ovarian androgen-secreting tumors are exceedingly rare but should be considered in patients with rapid-onset virilization or markedly elevated serum androgens.3,12,49 If physical stigmata of cortisol excess are present, Cushing syndrome may be excluded by a 24-hour urinary free cortisol, late-night salivary cortisol, or dexamethasone suppression test.2,12,49

Chronic Disease, Physiologic, and Induced Causes

Patients with chronic disease may experience amenorrhea; however, these conditions are often recognized by individual signs and symptoms. Menopause should be considered in patients older than 40 years.15,16,54 Pregnancy, lactation, hormonal contraceptives, and exogenous androgens (e.g., transgender care) may also cause amenorrhea.2,3,6

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Klein and Poth,3 and Master-Hunter and Heiman.55

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the MeSH function with the key phrase amenorrhea and one of the following: diagnosis, evaluation, management, or treatment. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews published after August 1, 2011. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Search dates: April 18 to July 16, 2018, and January 20, 2019.

The contents of this article are solely the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. military at large, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.