Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(2):98-108

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

More than 30 million U.S. adults have hearing loss. This condition is underrecognized, and hearing aids and other hearing enhancement technologies are underused. Hearing loss is categorized as conductive, sensorineural, or mixed. Age-related sensorineural hearing loss (i.e., presbycusis) is the most common type in adults. Several approaches can be used to screen for hearing loss, but the benefits of screening are uncertain. Patients may present with self-recognized hearing loss, or family members may observe behaviors (e.g., difficulty understanding conversations, increasing television volume) that suggest hearing loss. Patients with suspected hearing loss should undergo in-office hearing tests such as the whispered voice test or audiometry. Patients should then undergo examination for cerumen impaction, exostoses, and other abnormalities of the external canal and tympanic membrane, in addition to a neurologic examination. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (loss of 30 dB or more within 72 hours) requires prompt otolaryngology referral. Laboratory evaluation is not indicated unless systemic illness is suspected. Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is indicated in patients with asymmetrical hearing loss or sudden sensorineural hearing loss, and when ossicular chain damage is suspected. Treating cerumen impaction with irrigation or curettage is potentially curative. Other aspects of treatment include auditory rehabilitation, education, and eliminating or reducing use of ototoxic medications. Patients with sensorineural hearing loss should be referred to an audiologist for consideration of hearing aids. Patients with conductive hearing loss or sensorineural loss that does not improve with hearing aids should be referred to an otolaryngologist. Cochlear implants can be helpful for those with refractory or severe hearing loss.

More than 30 million U.S. adults, or nearly 15% of all Americans, have some degree of hearing loss.1 It is most common in older adults, occurring in about one-half of adults in their 70s and 80% of those 85 years and older.1,2 Despite this high prevalence, hearing loss is underdetected and undertreated. Only about one-third of people with self-reported hearing loss have ever had their hearing tested, and only 15% of people eligible for hearing aids consistently use them, citing factors such as cost, difficulty using them, and social stigma.1,3,4

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC

The FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 allows direct-to-consumer sale of hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss, for which limited outcome studies show improved hearing, communication, and social engagement. The cost of over-the-counter hearing aids is expected to range from approximately $200 to $1,000 compared with $800 to $4,000 for conventional hearing aids.

Among patients with dementia in a U.S. population-based longitudinal cohort study, the use of hearing aids was associated with decreased social isolation and a slower rate of cognitive decline, even after adjusting for multiple confounders.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the American Academy of Family Physicians conclude that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for hearing loss in asymptomatic adults 50 years and older.22,28 | C | Based on randomized controlled trials and observational studies with disease-oriented outcomes. The only good-quality randomized trial of hearing screening included many patients with baseline concerns about hearing loss; there was no improvement in hearing-related quality of life. |

| Patients with suspected presbycusis should be referred for audiometry. Laboratory evaluation or imaging is not needed initially.12,13,17,29 | C | Based on expert opinion and clinical reviews |

| Patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss should be referred to an otolaryngologist for audiologic evaluation.33 | C | Based on a clinical practice guideline |

| Information on hearing aid use should be provided to patients. It should incorporate patient expectations, perceived self-benefit, satisfaction, readiness to accept change, and support from significant others.38,39 | C | Systematic reviews on hearing aid use found only limited evidence for increased use of hearing aids when these factors are incorporated into the treatment plan. |

| Over-the-counter hearing aids should be recommended for patients with mild hearing loss.49–51 | C | Based on a low-quality study and expert opinion. Over-the-counter hearing aids are now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for mild to moderate hearing loss, but the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommends these devices only for patients with mild hearing loss. |

| Recommendations from the Choosing Wisely Campaign | |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order computed tomography of the head/brain for sudden hearing loss. | American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation |

Hearing loss is associated with adverse effects, even after adjusting for confounding factors. Difficulty hearing speech adversely affects social engagement and partner relationships. Hearing loss is also associated with decreased quality of life, dementia, depression, debility, delirium, falls, and mortality.5–7 Medical costs resulting from hearing impairment are estimated to range from $3.3 million to $12.8 million annually in the United States.8 This includes direct medical costs, disability expenditures, and indirect costs from lost productivity and caregiver expenses.

Classification

Hearing loss is grouped into conductive, sensorineural, or mixed types. Conductive problems involve the tympanic membrane and middle ear, and interfere with transmitting sound and converting it to mechanical vibrations (Table 1).9–15 Sensorineural problems affect the conversion of mechanical sound to neuroelectric signals in the inner ear or auditory nerve (Table 2).9–15

| Location | Condition | Typical history* | Physical examination findings† | Management‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle ear | Cholesteatoma | Recurrent otitis media, history of perforation, gradual onset of hearing loss, otorrhea, otalgia late | Tympanic membrane with retraction pocket and debris; white mass behind tympanic membrane | Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography of temporal bone; excision, often with mastoidectomy, with ossicular chain reconstruction if possible |

| Ossicular chain disruption | Trauma, recurrent otitis media | Usually normal; sometimes abnormal location of malleus or incus | Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography of temporal bone; ossicular chain reconstruction | |

| Otitis media with effusion§ | Fever, otalgia | Erythematous tympanic membrane; immobile on pneumatic otoscopy | Antibiotics, expectant management; myringotomy for refractory effusion | |

| Otosclerosis§ | Gradual, painless, bilateral hearing loss presenting at 30 to 50 years of age; tinnitus; better at hearing speech in noisy environments | Tympanic membrane usually normal | Hearing aid; consider stapedectomy or other surgical procedure | |

| Pinna, external auditory canal | Obstruction of external canal by cerumen§ | Gradual onset; otalgia uncommon | Occlusive cerumen | Cerumen removal by irrigation or curettage |

| Obstruction of external canal by exostoses (surfer's ear) | Gradual onset; otalgia uncommon | Abnormally shaped canal with mass | Excision of obstructing exostosis | |

| Obstruction of external canal by foreign body | Gradual onset; otalgia uncommon | Foreign body in canal | Foreign body removal | |

| Otitis externa | Otalgia, drainage | Inflamed canal with debris | Topical antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory | |

| Tympanic membrane | Perforation, tympanosclerosis | Barotrauma or head/ear trauma, recent or recurrent otitis media | Visible defect or scarring | Antibiotics if infection present; tympanoplasty if perforation not healed within two months; referral and imaging for vertigo, severe symptoms, or facial paralysis |

| Condition | Typical history* | Physical examination findings† | Management‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune condition (idiopathic or part of recognized autoimmune disease) | Bilateral, rapidly progressive hearing loss; ataxia; vertigo; symptoms of recognized autoimmune disease | Usually normal | Autoimmune laboratory evaluation, immunosuppressive drugs, transtympanic corticosteroids |

| Cerebellopontine angle tumor/neoplasm | Hearing loss that is usually slowly progressive and unilateral, but sometimes sudden; tinnitus; headache (late); vertigo (typically mild) | Usually normal; some patients have ataxia, facial weakness, or decreased facial sensation | Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, surgical excision |

| Infectious condition (e.g., meningitis, labyrinthitis) | May be a complication of otitis media; hearing loss develops over hours to days; respiratory symptoms and vertigo may be present | Signs of otitis media; nuchal rigidity and fever in meningitis; nystagmus and ataxia in labyrinthitis | Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, lumbar puncture; antibiotics for meningitis; expectant management or vestibular rehabilitation for labyrinthitis; consultation with otolaryngologist, neurologist, or infectious disease subspecialist |

| Meniere disease | Episodic, fluctuating ear fullness associated with tinnitus, hearing loss, and vertigo | Often normal; during episode may have rotary nystagmus and ataxia, and noises may seem much louder than they are (auditory recruitment) | Acute episodes can be treated with vestibulosuppressants (e.g., antihistamines, benzodiazepines); long-term treatments include diuretics, vestibular balance/rehabilitation therapy, transtympanic injection of corticosteroids or gentamicin, or surgery (e.g., decompression of endolymphatic sac) |

| Noise exposure§ | Acute exposure to sudden loud (130 dB) impulse (acoustic trauma); chronic exposure to loud (85 dB) noises; tinnitus | Normal | Prevention; referral to audiologist for possible hearing aid; referral to otolaryngologist if hearing aid is ineffective or for consideration of cochlear implant for profound hearing loss Acoustic trauma lasts hours to days (typically resolves within 48 hours) |

| Ototoxin exposure | Hearing loss develops over weeks; exposure to medications or industrial toxins (eTable A) | Normal | Prevention, referral to audiologist, hearing aid |

| Presbycusis§ | Older age, family history | Normal | Referral to audiologist for possible hearing aid; referral to otolaryngologist if hearing aid is ineffective or for consideration of cochlear implant for profound hearing loss |

| Trauma | Current or past head or neck trauma | Signs of other head or neck injuries, hematoma of ear or mastoid, hemotympanum, tympanic membrane perforation | Non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography, referral to trauma subspecialist or otolaryngologist |

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, is the most common type of sensorineural loss. The cause of presbycusis is multifactorial, with contributions from genetic factors, aging, oxidative stress, cochlear vascular changes, and environmental factors (e.g., noise, tobacco, alcohol, ototoxins).16–18

There is no universally accepted definition of hearing impairment, nor is there a universally adopted scale of hearing loss. However, some widely used descriptions are listed in Table 3.19–21 Characterizing hearing loss requires pure tone audiometry. A person with normal hearing can hear sounds as soft as 25 dB; conversational speech is 45 to 60 dB.

| Severity | Degree of hearing loss in better ear (dB) | Examples of sounds that can or cannot be heard | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clark model19 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention model20 | World Health Organization model21 | ||

| Normal | 10 to 15 | ≤ 25 | ≤ 25 | Can hear normal breathing |

| Slight | 16 to 25 | — | — | Infrequent difficulty in some situations; can hear whispering from 5 ft (1.5 m) away |

| Mild | 26 to 40 | 26 to 40 | 26 to 40 | Difficulty hearing soft speech, quiet library sounds, or speech from a distance or over background noise |

| Moderate | 41 to 55 | 41 to 55 | 41 to 60 | Difficulty hearing regular speech, even at close distances, or sound of a refrigerator |

| Moderately severe | 56 to 70 | 56 to 70 | — | Extreme difficulty hearing normal conversation; can hear electric toothbrush |

| Severe | 71 to 90 | 71 to 90 | 61 to 80 | Cannot hear most conversational speech, only loud speech or sounds (e.g., an alarm clock) |

| Profound | ≥ 91 | ≥ 91 | ≥ 81 | May perceive loud sounds (e.g., factory machinery, car horn) as vibrations |

Clinical Aspects

SCREENING

Screening for decreased hearing in asymptomatic people can be done in several ways. One is the use of self-administered questionnaires; a validated questionnaire is available at https://www.asha.org/public/hearing/Self-Test-for-Hearing-Loss/. In-office hearing tests are the most accurate for ruling out hearing loss (Table 4).14,15,22–25 Of these, the finger rub test, the whispered voice test, and audiometry (automated handheld or manual tabletop) are the most accurate and easy to use.12,13,15,24 Remote screening is feasible and reasonably accurate (sensitivity of various tests = 87% to 100%; specificity = 60% to 96%), and a variety of tests are available online or as smartphone apps.26 However, there are concerns about variability of results and interference from ambient noise.

| Test | Description | Hearing loss threshold | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Likelihood ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||||

| Clinical examination | |||||||

| Finger rub test | Examiner gently rubs fingers together 6 inches from patient's ear; a positive result is failure to identify the rub in at least three of six attempts | > 25 dB | 98 | 75 | 10 | 0.75 | |

| Whispered voice test | Examiner stands at arm's length behind patient, and patient occludes one ear while examiner whispers letter/number combinations six times; a positive test is inability to repeat at least three of the six letter/number combinations | 30 dB | 95 | 82 | 5.1 | 0.03 | |

| Direct question | Yes or no question to patient about whether he or she has hearing loss | > 25 dB | 67 | 80 | 3.0 | 0.4 | |

| > 40 dB | 81 | 72 | 2.5 | 0.26 | |||

| Handheld audiometry | Examiner holds device in patient's ear, and patient indicates awareness of each tone; a positive test is failure to identify the 1,000-Hz or 2,000-Hz frequency in both ears, or the 1,000-Hz and 2,000-Hz frequency in one ear | 30 to 45 dB | 96 | 72 | 3.4 | 0.05 | |

| Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly | 10-item, self-administered questionnaire measuring social and emotional handicap due to hearing impairment; score > 8 is abnormal | > 25 dB | 75 | 67 | 3.8 | 0.38 | |

| Tabletop manual audiometry | Various models of small, portable audiometers or audiometric program designed for portable electronic devices | ≥ 40 dB | 88 | 96 | 21.3 | 0.13 | |

| Tuning fork tests (512 Hz) | |||||||

| Rinne test | Examiner strikes a tuning fork and places it on mastoid bone behind ear, then when patient indicates no further sound, the still-vibrating fork is moved to the ear (air conduction will be better than bone conduction); inability to detect air-conducted sound indicates conductive hearing loss | 20 dB | 65 | 95 to 98 | 2.7 to 62* | – 0.01 to 0.85* | |

| Weber test | Examiner strikes a tuning fork and places it midforehead; normal result is perceiving sound on both sides (no lateralization) | Lateralization to good ear indicates sensorineural hearing loss | 58 | 79 | 1.6 | 0.7 | |

| Lateralization to bad ear indicates conductive hearing loss | 54 | 92 | Not specified | 0.5 | |||

Despite the availability of these screening modalities, there are questions about whether screening is worthwhile. There have been few studies on the issue, and the only good-quality study evaluated screening in people with self-perceived hearing loss at baseline.27 Thus, the population studied was not asymptomatic, and there was no improvement in hearing-related quality of life. This has led the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to conclude that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for hearing loss in asymptomatic adults 50 years or older.22 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports this conclusion.28

HISTORY

People with hearing impairment may present with self-recognized hearing loss or concerns from family members who have observed difficulty understanding everyday conversation, turning up television volume, frequently asking others to repeat things, social avoidance, and difficulty hearing with background noise. People with decreased hearing may also present with sensitivity to loud noises, tinnitus, or vertigo.12,13 The history can suggest an etiology and help in planning treatment.

Presbycusis characteristically involves gradual onset of bilateral high-frequency hearing loss associated with difficulty in speech discrimination. Conversations with background noise become difficult to understand.18

Clinicians should ask about duration of hearing loss and whether symptoms are bilateral, fluctuating, or progressive. The evaluation should also include a neurologic review; history of diabetes mellitus, stroke, vasculitis, head or ear trauma, and use of ototoxic medications; and family history of ear conditions and hearing loss.9–11

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Important physical examination components are listed in Table 1 and Table 2.9–15 The ear should be examined for cerumen impaction, exostoses, or other abnormalities of the external canal, in addition to perforation or retraction of or effusion behind the tympanic membrane. An atlas of otoscopy that illustrates key findings is available at http://www.entusa.com/eardrum_and_middle_ear.htm.

Examination should include the cranial nerves because tumors of the auditory nerve (acoustic neuroma) and stroke may affect cranial nerves V and VII. The head and neck should be examined for masses and lymphadenitis; if present, they suggest infection or cancer.12,13 Bedside hearing tests and tuning fork tests can help determine the presence and type of hearing loss.15

AUDIOMETRIC EVALUATION

Patients in whom hearing loss is suspected should be referred for pure tone audiometry, in which signals are delivered through air conduction and bone conduction to assess hearing thresholds.12,13,29 This differentiates conductive from sensorineural hearing loss and characterizes the pattern of hearing loss at various frequencies. A complete audiologic evaluation also includes evaluation of speech perception in quiet and with background noise, and may include tympanometry, acoustic reflex, otoacoustic emissions, and auditory evoked potentials (Table 5).15,20,30,31

| Component | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing health history | Questions about symptom duration and variability, tinnitus, vertigo, trauma, medical conditions, medications, noise and ototoxin exposure, family history | Often completed via questionnaire |

| Hearing-focused physical examination | Inspection of external ear and otoscopy | Must exclude cerumen impaction before further testing |

| Pure tone audiometry | Pure tones presented to one ear at a time via headphones or earbuds, typically in a sound booth | Determines softest level at which each frequency can be heard (pure tone threshold) |

| Speech reception threshold | Recorded or live speech presented to one ear at a time via headphones or earbuds | Determines softest level at which speech can be heard |

| Speech discrimination (word recognition score) | Syllables repeated to each ear at volume previously identified as hearable | May identify central processing difficulties not expected based solely on hearing ability |

| Hearing in noise test | Sentences repeated in quiet and with background noise; competing noise comes from varying directions | Patients with presbycusis typically have more difficulty hearing with background noise; helps predict signal-to-noise ratio that may be needed in hearing aids; directional hearing loss not explained by pure tone thresholds may reflect central auditory processing problem |

| Immittance audiometry: tympanometry and acoustic reflex | Occlusive probe inserted into canal that generates pressure | Can characterize conductive and sensorineural hearing loss; acoustic reflex decay (contraction of middle ear muscles to decrease transmission of sound, which should occur only with loud sounds) suggests retrocochlear (central nervous system) pathology |

| Bone conduction | Small bone oscillator placed over mastoid | Used to characterize conductive hearing loss |

| Auditory evoked potentials (auditory brainstem response) | Click introduced by earphone or headphone; transmission through brainstem to auditory cortex measured by scalp electrodes | Often used for newborn hearing screening |

| Otoacoustic emissions | Click introduced in ear canal with measurement of emissions from inner ear (cochlea) by microphone | Measures integrity of cochlea and, indirectly, middle ear; can be used for newborn screening; highly sensitive but less specific than auditory evoked potentials |

ADDITIONAL EVALUATION

Laboratory evaluation for primary care patients with hearing loss is not indicated unless systemic illness is suspected. There is no need for imaging if the hearing loss pattern suggests presbycusis.12 However, imaging is useful to evaluate and characterize conductive hearing loss, asymmetrical hearing loss (a difference of at least 15 dB at 3,000 Hz),32 and sudden sensorineural hearing loss (loss of at least 30 dB in less than 72 hours).33 Patients with these conditions should be referred to an otolaryngologist for imaging and further evaluation.12

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Depression and dementia should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hearing loss. Both conditions may present with the apathy, inattentiveness, and social disengagement that can occur with hearing loss. Patients with dementia should be evaluated for hearing loss because hearing impairment can create disengagement and make cognitive impairment seem more severe than it is.5,6 Similarly, if hearing loss is detected, cognitive screening should be performed because cognitive impairment often accompanies hearing loss.

Primary Care Management

An audiologist will typically assume responsibility for treating patients in whom hearing aids are indicated. However, family physicians still have an essential role in caring for these patients. Important considerations for primary care clinicians are summarized by the SCREAM mnemonic: sudden hearing loss, cerumen impaction, auditory rehabilitation, education, assistive devices, and medications (Table 6).33–43

| Concern | Description | Evaluation | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudden hearing loss (idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss) | Development of ≥ 30 dB hearing loss at three consecutive frequencies over 72 hours or less | Rule out conductive hearing loss or readily identifiable cause | Identify hearing loss by in-office tests and directed history and physical examination; urgent referral (within one week) to otolaryngologist |

| Cerumen impaction | Occlusive cerumen causing hearing loss | Otologic examination | Canal irrigation with or without cerumenolytics or manual extraction of cerumen |

| Auditory rehabilitation | Training and treatment to improve the hearing environment | Determine patient's and family members' current habits and knowledge | Provide information about improving environment and communication strategies* |

| Education | Information for the patient and his or her family about hearing loss, evaluation, hearing protection, and management | Determine patient's knowledge, beliefs, and stage of change | Provide resources on hearing protection and expectations, benefits, and use of hearing aids |

| Assistive devices | Technology to augment hearing, including over-the-counter assistive devices | Determine whether patient is a candidate for over-the-counter assistive devices or audiologic assessment for hearing aids | Patients with mild sensorineural hearing loss may try over-the-counter devices initially; instruct patients on other technologies (e.g., television and telephone amplification) |

| Medications | Evaluating and mitigating medications with ototoxicity | Determine current and past use of ototoxic medications | Discontinue or avoid unnecessary ototoxic medications (eTable A); mitigate ototoxicity by assuring adherence to protocols when such drugs are needed |

SUDDEN SENSORINEURAL HEARING LOSS

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss refers to hearing loss of at least 30 dB involving three consecutive frequencies occurring over less than 72 hours for which no apparent cause can be found on initial history and examination. History and physical examination findings may suggest a treatable etiology (Table 7).33–35 If no cause requiring emergency intervention is identified, hearing loss should be confirmed with audiometry, and consultation with an otolaryngologist should occur within one week.33

| Type of hearing loss | Cause | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic (80% to 90% of cases) | Unknown | Corticosteroids; hyperbaric oxygen in younger patients unresponsive to corticosteroids |

| Infectious | Epstein-Barr virus, group A streptococcus, herpes simplex virus, herpes zoster virus, HIV,* Lyme disease,* meningitis, syphilis | Specific antimicrobial if identified |

| Otologic | Autoimmune condition, Meniere disease | Vestibulosuppressants for vertigo, corticosteroids, diuretics, surgery for Meniere disease |

| Trauma | Barotrauma, ear trauma, or head trauma | Manage trauma; otologic surgery when stable |

| Vascular | Cerebrovascular disease | Stroke management |

| Neoplastic | Angioma, hyperviscosity,* meningioma, neurofibromatosis 2, schwannoma | Surgical excision; radiation therapy in select cases |

| Other | Genetic cause,* mitochondrial disorder,* ototoxins,* pregnancy | Avoid ototoxins; treat underlying disorder if possible |

Although a Cochrane review found unclear benefit for the use of glucocorticoids for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss, some studies have found benefit from systemic or intratympanic steroids, and referral to an otolaryngologist for this treatment is the standard of care.34 If steroids are used, they should be started within two weeks. Limited data show that hyperbaric oxygen therapy may improve outcomes in younger patients if started within two weeks. This therapy is usually reserved for patients who do not respond to steroids.35

CERUMEN IMPACTION

Occlusion of the external auditory canal by cerumen results in conductive hearing loss, and removal is curative. Cerumen can be removed by irrigation, manual extraction, cerumenolytic agents, or a combination of these methods. Evidence is limited to support one method of removal over others.36 Because of minimal training requirements, favorable side effects, and effectiveness, irrigation may be the optimal method of removal in primary care practices. The effectiveness and safety of jet irrigators vs. syringe irrigation have not been studied. Data supporting the use of cerumenolytics are limited, and some studies conclude that they offer no advantage over irrigation alone.36,44,45

AUDITORY REHABILITATION

Auditory rehabilitation has been variably defined, but it generally refers to services that focus on adjusting patients and their families to hearing deficits and providing listening and speaking strategies to improve communication. These strategies include facing people when talking, improving lighting, minimizing background noise, summarizing what was heard, and rephrasing. This practice is generally regarded as beneficial, but studies supporting auditory rehabilitation are mostly of poor quality.37 A patient handout on communication strategies is available at https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/hearing-loss-common-problem-older-adults#communicate.

EDUCATION

Clinicians should provide information about the nature and causes of hearing loss, hearing aids (if applicable), and hearing protection. There is poor adherence to hearing conservation programs and personal hearing protection.3,46,47 Patient expectations, perceived self-benefit, satisfaction, readiness for change, and support from family are important determinants of hearing aid use.38,39 Strict standards are in place for noise and ototoxin exposure in work settings, but patients may not use the same protections with home activities.

ASSISTIVE DEVICES

Clinicians can help patients ameliorate communication challenges by being aware of available hearing technologies (discussed in the following section) and their appropriateness for individual patients.

MEDICATIONS

Hundreds of medications are associated with ototoxicity (eTable A). Physicians should ask about current and past use of these medications, and when current use is necessary, assure that protocols are in place to minimize risk. Ototoxicity is typically dose-dependent and more likely to occur in patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease.40,41 Guidelines for monitoring patients for ototoxicity are available from the American Academy of Audiology.48

| Substance | Risk factors for exposure |

|---|---|

| Chemicals, metals, and other toxins Asphyxiants: carbon monoxide, tobacco smoke Metals: lead, mercury compounds, organic tin compounds Nitriles: acrylonitrile, 3-butenenitrile Solvents: p-xylene, styrene, toluene, trichloroethylene | Automotive repair; boat building; construction; manufacturing of metal, leather, petroleum products, or batteries; occupational or household painting; pesticide spraying; smoking; vehicle or aircraft fueling |

| Pharmaceuticals Aminoglycoside antibiotics (e.g., gentamicin, streptomycin) Other antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin,* tetracyclines*) Analgesics* and antipyretics* (e.g., acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, salicylates) Antineoplastic agents (e.g., bleomycin, carboplatin, cisplatin) Loop diuretics* (e.g., ethacrynic acid, furosemide [Lasix]) Other drugs* (chloroquine [Aralen], hydrocodone, misoprostol [Cytotec], phosphodiesterase inhibitors, quinine) | Chemotherapy, congestive heart failure, hospital inpatients, renal disease |

Assistive Technologies

HEARING ASSISTIVE DEVICES

Hearing assistive devices include visual cues for doorbells, telephones, or alarms, and sound amplifiers for televisions, telephones, or theaters. In public venues such as theaters, assistive listening systems are required to be accessible for people with hearing impairment, even if they do not have hearing aids. These systems transmit sound from a public system to the telecoil of a hearing aid or to specialized headphones using FM radio, electromagnetic field induction loops, or infrared systems.42

DIRECT-TO-CONSUMER HEARING AIDS

The FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 includes an amendment allowing direct-to-consumer sales of hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss.43 Although there are limited outcome studies, they show improved hearing, communication, and social engagement with these devices.49 The cost of over-the-counter hearing aids is expected to range from approximately $200 to $1,000 compared with $800 to $4,000 for conventional hearing aids. The American Academy of Audiology and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association recommend that these devices be restricted to patients with mild hearing loss and note that the best outcomes are achieved with a comprehensive audiologic evaluation and rehabilitation program.50,51 A recent study found slightly better speech recognition and lower listening effort with fitted hearing aids vs. personal sound amplifying devices, but both devices improved hearing performance over baseline.52

CONVENTIONAL HEARING AIDS

Multiple studies show that hearing aids provide benefit.53 A 2017 Cochrane review of hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss found evidence that these devices improve hearing-related quality of life and overall health-related quality of life.54 The use of hearing aids in patients with dementia decreases social isolation and slows cognitive decline, even after adjusting for multiple confounders.55

There are several types of hearing aids to accommodate various patient requirements and preferences (eTable B). Digital processing has permitted many adaptive features, such as improved sound quality, multiple listening programs for different environments, advanced noise reduction strategies, acoustic feedback reduction, remote control options, and the ability for the user to adjust volume across frequencies.

| Hearing aid type | Description | Available as | Discreteness | Ease of use | Risk of damage from cerumen and moisture | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behind the ear | All parts are in a small case at the back of the ear and are joined to the ear canal with a sound tube and a custom mold or tip | Mini, standard, or powered | Least | Easiest | Least | Typically the most fully functional with the most available hardware and software; may include telecoil for listening in public places; can be used for all degrees of hearing loss |

| Receiver in canal | Similar to behind-the-ear hearing aids, except the receiver (speaker) has been removed from the case and moved into the canal, and is connected to the case with a thin wire | Receiver in the ear | Very | Moderate | Moderate | Contraindications include permanent tympanic membrane perforation, mastoid surgery, and excessive cerumen; easy to change receivers; typically limited to mild to moderate hearing loss |

| In the ear | Custom-made devices; all of the electronics sit in a device that fits in the ear | Completely in canal, invisible in canal, or mini in canal | Usually most | Usually requires most dexterity | Moderate | Contraindications include permanent tympanic membrane perforation, mastoid surgery, and excessive cerumen; typically limited to mild to moderate hearing loss |

Audiologists measure and adjust the hearing aid's functions (e.g., volume at each frequency, intensity, microphone power output, compression ratios) based on individual patient requirements. They also provide education and training in the use and handling of hearing aids and audiologic rehabilitation. An audiologist should refer patients to an otolaryngologist for evaluation and treatment of conductive hearing loss, sudden sensorineural hearing loss, asymmetrical hearing loss, or failure of hearing to improve with hearing aids.

COCHLEAR IMPLANTS AND OTHER SURGICAL INTERVENTIONS

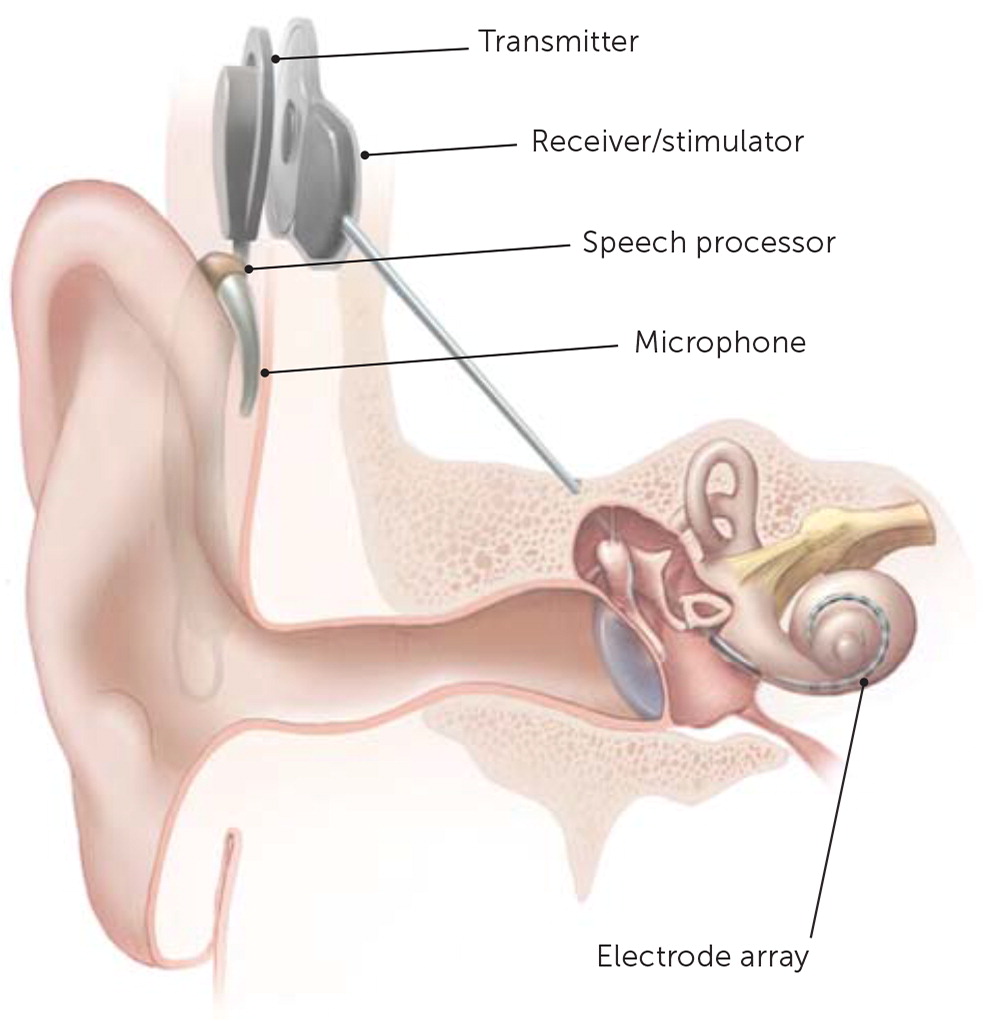

Most causes of conductive hearing loss are potentially correctable with surgery. However, cochlear implants are used for moderate to profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. A cochlear implant is a surgically placed device that bypasses damaged portions of the ear and directly stimulates the auditory nerve (Figure 1). Medicare covers approved cochlear implants if patients meet hearing loss criteria and have limited benefit from hearing aids, do not have middle ear disease, and have the cognitive ability to use them.56,57 Studies show benefit in speech perception, social function, and overall quality of life after placement of cochlear implants.58 Cochlear implants and other surgical treatments for hearing loss are summarized in eTable C.

| Type of hearing loss | Condition | Surgical procedure | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive* | Cholesteatoma | Excision, ossicular chain reconstruction | Treatment depends on location and severity |

| Chronic middle ear effusion | Myringotomy with pneumatic equalization tube insertion | Often secondary to refractory eustachian tube dysfunction | |

| Malformations of pinna or external auditory canal (e.g., osteomas, exostoses), foreign body | Resection of osteoma or exostosis, reconstructive procedures, foreign body removal | May allow fitting of traditional hearing aid if indicated | |

| Ossicular chain disruption, erosion | Ossicular chain reconstruction | Can be caused by trauma, infection, otosclerosis, cholesteatoma, or tumors | |

| Otosclerosis | Stapedectomy with prosthesis, ossicular chain reconstruction | Should be free from other external or middle ear disease | |

| Tympanic membrane perforation† | Tympanoplasty, myringoplasty | For conditions limited to tympanic membrane | |

| Sensorineural | Meniere disease | Endolymphatic sac decompression, vestibular nerve section, labyrinthectomy | For severe symptoms not controlled with medication, noninvasive therapy, or middle ear injections |

| Moderate to profound sensorineural hearing loss with limited benefit from hearing aids | Cochlear implant | Microphone behind ear transmits to processor placed under skin, which converts sound to electronic signals to transmitter and through implanted electrodes to cochlea (bypasses hair cells) | |

| Severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss with relatively preserved hearing at lower frequencies | Electroacoustic stimulation (hybrid cochlear implant) | Cochlear implant placed into basal turn of cochlea (high-frequency area) with hearing aid to amplify residual low-frequency hearing | |

| Unilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss | Bone-anchored hearing aid: external portion attaches over device imbedded in bone and transmits vibration to skull | Percutaneous osseointegrated titanium post implanted in the postauricular skull stimulates cochlea in the better ear | |

| Mixed | Malformed ear, inability to use hearing aid, unilateral profound loss with excellent hearing in contralateral ear | Bone-anchored hearing aid: external portion attaches over device imbedded in bone and transmits vibration to skull | Requires functioning cochlea, at least in the good ear |

| Stable bilateral moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss with relatively preserved word recognition and limited benefit or adverse local reaction to hearing aid | Implantable middle ear hearing device: microphone conducts sound to middle ear transducer | Requires functioning cochlea, at least in the good ear |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Walling and Dickson,9 and by Isaacson and Vora.59

Data Sources: The authors used the key words hearing loss and hearing impairment to search PubMed, the Cochrane database, USPSTF, BMJ Best Evidence, Essential Evidence Plus, JAMA Evidence, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, and Trip database. Additional queries in PubMed were made for specific topics addressed. Search dates: August 15, 2018; November 16, 2018; and April 25, 2019.

Figure 1 courtesy of National Institutes of Health Medical Arts and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

The authors thank June Hensley, MA, CCC-A, for her review of the manuscript.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Department or the U.S. Army Service at large.