Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(10):599-606

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

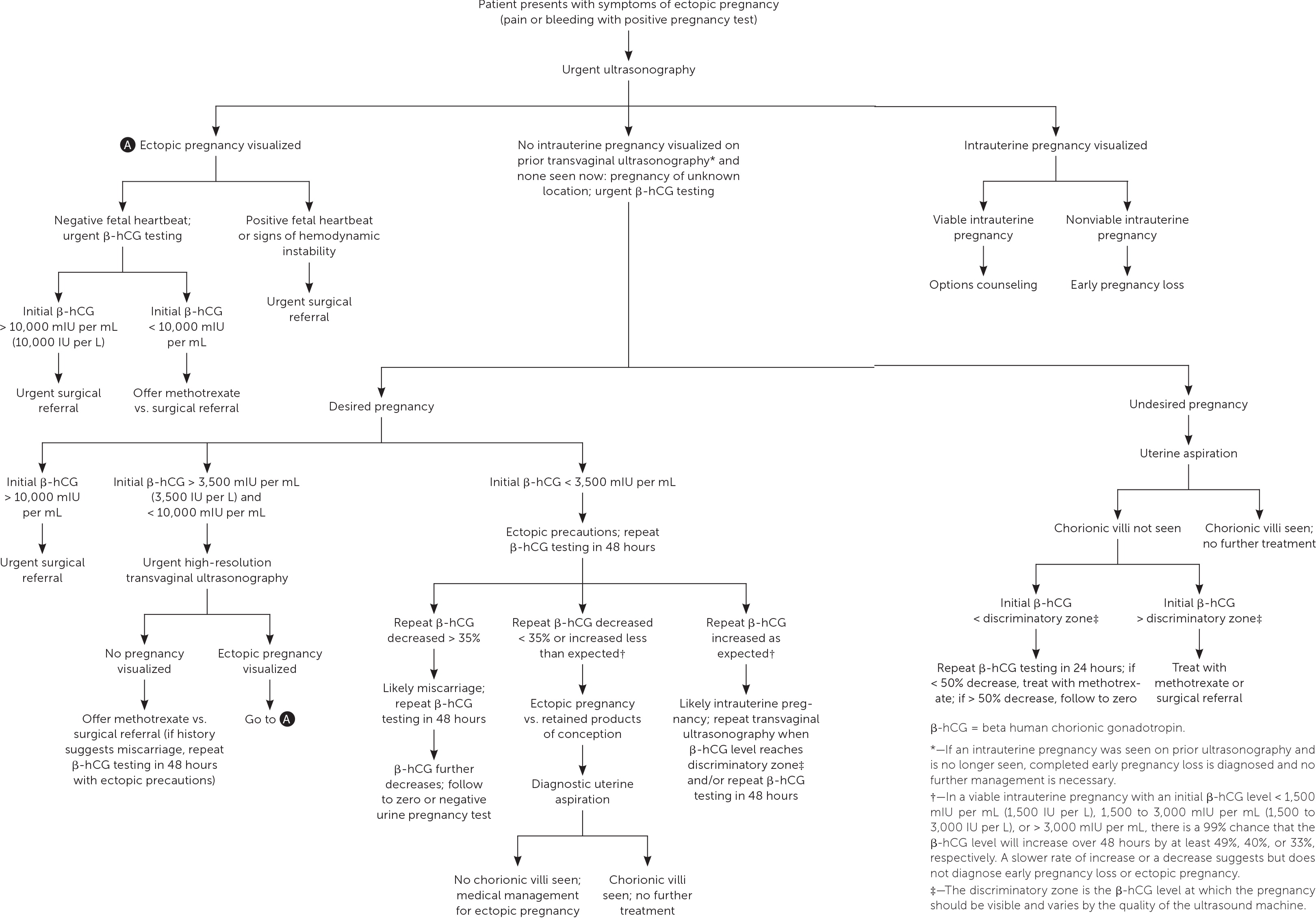

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized ovum implants outside of the uterine cavity. In the United States, the estimated prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is 1% to 2%, and ruptured ectopic pregnancy accounts for 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths. Risk factors include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, cigarette smoking, fallopian tube surgery, previous ectopic pregnancy, and infertility. Ectopic pregnancy should be considered in any patient presenting early in pregnancy with vaginal bleeding or lower abdominal pain in whom intrauterine pregnancy has not yet been established. The definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can be made with ultrasound visualization of a yolk sac and/or embryo in the adnexa. However, most ectopic pregnancies do not reach this stage. More often, patient symptoms combined with serial ultrasonography and trends in beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels are used to make the diagnosis. Pregnancy of unknown location refers to a transient state in which a pregnancy test is positive but ultrasonography shows neither intrauterine nor ectopic pregnancy. Serial beta human chorionic gonadotropin levels, serial ultrasonography, and, at times, uterine aspiration can be used to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. Treatment of diagnosed ectopic pregnancy includes medical management with intramuscular methotrexate, surgical management via salpingostomy or salpingectomy, and, in rare cases, expectant management. A patient with diagnosed ectopic pregnancy should be immediately transferred for surgery if she has peritoneal signs or hemodynamic instability, if the initial beta human chorionic gonadotropin level is high, if fetal cardiac activity is detected outside of the uterus on ultrasonography, or if there is a contraindication to medical management.

Ectopic pregnancy occurs when a fertilized ovum implants outside of the uterine cavity. The prevalence of ectopic pregnancy in the United States is estimated to be 1% to 2%, but this may be an underestimate because this condition is often treated in the office setting where it is not tracked.1,2 The mortality rate for ruptured ectopic pregnancy has steadily declined over the past three decades, and from 2011 to 2013 accounted for 2.7% of pregnancy-related deaths.1,3 Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy are listed in Table 14,5; however, one-half of women with diagnosed ectopic pregnancy have no identified risk factors.4–6 The overall rate of pregnancy (including ectopic) is less than 1% when a patient has an intrauterine device (IUD). However, in the rare case that a woman does become pregnant while she has an IUD, the prevalence of ectopic pregnancy is as high as 53%.7,8 There is no difference in ectopic pregnancy rates between copper or progestin-releasing IUDs.9

| Age > 35 years Cigarette smoking Documented fallopian tube pathology Infertility Pelvic inflammatory disease Pregnancy while intrauterine device is in place Previous ectopic pregnancy* Previous fallopian tube surgery |

Making the Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Ectopic pregnancy should be considered in any pregnant patient with vaginal bleeding or lower abdominal pain when intrauterine pregnancy has not yet been established (Table 2).10 Vaginal bleeding in women with ectopic pregnancy is due to the sloughing of decidual endometrium and can range from spotting to menstruation-equivalent levels.10 This endometrial decidual reaction occurs even with ectopic implantation, and the passage of a decidual cast may mimic the passage of pregnancy tissue. Thus, a history of bleeding and passage of tissue cannot be relied on to differentiate ectopic pregnancy from early intrauterine pregnancy failure.

| Appendicitis Early pregnancy loss Ectopic pregnancy Ovarian torsion Pelvic inflammatory disease Subchorionic hemorrhage in viable intrauterine pregnancy Trauma Urinary calculi |

The nature, location, and severity of pain in ectopic pregnancy vary. It often begins as a colicky abdominal or pelvic pain that is localized to one side as the pregnancy distends the fallopian tube. The pain may become more generalized once the tube ruptures and hemoperitoneum develops. Other potential symptoms include presyncope, syncope, vomiting, diarrhea, shoulder pain, lower urinary tract symptoms, rectal pressure, or pain with defecation.11

The physical examination can reveal signs of hemodynamic instability (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia) in women with ruptured ectopic pregnancy and hemoperitoneum.12 Patients with unruptured ectopic pregnancy often have cervical motion or adnexal tenderness.13 Sometimes the ectopic pregnancy itself can be palpated as a painful mass lateral to the uterus. There is no evidence that palpation during the pelvic examination leads to an increased risk of rupture.10

BETA HUMAN CHORIONIC GONADOTROPIN

Beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) can be detected in pregnancy as early as eight days after ovulation.14 The rate of increase in β-hCG levels, typically measured every 48 hours, can aid in distinguishing normal from abnormal early pregnancy. In a viable intrauterine pregnancy with an initial β-hCG level less than 1,500 mIU per mL (1,500 IU per L), there is a 99% chance that the β-hCG level will increase by at least 49% over 48 hours.15 As the initial β-hCG level increases, the rate of increase over 48 hours slows, with an increase of at least 40% expected for an initial β-hCG level of 1,500 to 3,000 mIU per mL (1,500 to 3,000 IU per L) and 33% for an initial β-hCG level greater than 3,000 mIU per mL.15 A slower-than-expected rate of increase or a decrease in β-hCG levels suggests early pregnancy loss or ectopic pregnancy. The rate of increase slows as pregnancy progresses and typically plateaus around 100,000 mIU per mL (100,000 IU per L) at 10 weeks' gestation.16 A decrease in β-hCG of at least 21% over 48 hours suggests a likely failed intrauterine pregnancy, whereas a smaller decrease should raise concern for ectopic pregnancy.17

The discriminatory level is the β-hCG level above which an intrauterine pregnancy is expected to be seen on transvaginal ultrasonography; it varies with the type of ultrasound machine used, the sonographer, and the number of gestations. A combination of β-hCG level greater than the discriminatory level and ultrasonography that does not show an intrauterine pregnancy should raise concern for early pregnancy loss or an ectopic pregnancy.5 The discriminatory zone was previously defined as a β-hCG level of 1,000 to 2,000 mIU per mL (1,000 to 2,000 IU per L); however, this cutoff can miss some intrauterine pregnancies that do not become apparent until a slightly higher β-hCG level is achieved. Therefore, in a desired pregnancy, it is recommended that a discriminatory level as high as 3,500 mIU per mL (3,500 IU per L) be used to avoid misdiagnosis and interruption of a viable pregnancy, although most pregnancies will be visualized by the time the β-hCG level reaches 1,500 mIU per mL.18,19

TRANSVAGINAL ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Intrauterine pregnancy visualized on transvaginal ultrasonography essentially rules out ectopic pregnancy except in the exceedingly rare case of heterotopic pregnancy.5 The definitive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can be made with ultrasonography when a yolk sac and/or embryo is seen in the adnexa; however, ultrasonography alone is rarely used to diagnose ectopic pregnancy because most do not progress to this stage.5 More often, the patient history is combined with serial quantitative β-hCG levels, sequential ultrasonography, and, at times, uterine aspiration to arrive at a final diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

PREGNANCY OF UNKNOWN LOCATION

Ultrasonography showing neither intrauterine nor ectopic pregnancy in a patient with a positive pregnancy test is referred to as a pregnancy of unknown location. In a desired pregnancy, β-hCG levels and serial ultrasonography combined with patient reports of pain or bleeding guide management.20 In an undesired pregnancy or when the possibility of a viable intrauterine pregnancy has been excluded, manual vacuum aspiration of the uterus can evaluate for chorionic villi that differentiate intrauterine pregnancy loss from ectopic pregnancy. If chorionic villi are seen, further workup is unnecessary, and exposure to methotrexate can be avoided (Figure 1).5,15–17,21 If chorionic villi are not seen after uterine aspiration, it is imperative to initiate treatment for ectopic pregnancy or repeat β-hCG measurement in 24 hours to ensure at least a 50% decrease. Ectopic precautions and serial β-hCG levels should be continued until the level is undetectable.

Management of Ectopic Pregnancy

It is appropriate for family physicians to treat hemodynamically stable patients in conjunction with their primary obstetrician. Patients with suspected or confirmed ectopic pregnancy who exhibit signs and symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy should be emergently transferred for surgical intervention. If ectopic pregnancy has been diagnosed, the patient is deemed clinically stable, and the affected fallopian tube has not ruptured, treatment options include medical management with intramuscular methotrexate or surgical management with salpingostomy (removal of the ectopic pregnancy while leaving the fallopian tube in place) or salpingectomy (removal of part or all of the affected fallopian tube). The decision to manage the ectopic pregnancy medically or surgically should be informed by individual patient factors and preferences, clinical findings, ultrasound findings, and β-hCG levels.12 Expectant management is rare but can be considered with close follow-up for patients with suspected ectopic pregnancy who are asymptomatic and have β-hCG levels that are very low and continue to decrease.5

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Intramuscular methotrexate is the only medication appropriate for the management of ectopic pregnancy. A folate antagonist, it interrupts the rapidly dividing cells of the ectopic pregnancy, which are then resorbed by the body.22 Its success rate decreases with higher initial β-hCG levels (Table 3).23 Contraindications to methotrexate include renal insufficiency; moderate to severe anemia, leukopenia, or thrombocytopenia; liver disease or alcoholism; active peptic ulcer disease; and breastfeeding.5 Therefore, a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel should be obtained before it is administered.

| Initial beta human chorionic gonadotropin level (mIU per mL or IU per L) | Success rate (%) |

|---|---|

| < 1,000 | 98 |

| 1,000 to 1,999 | 94 |

| 2,000 to 4,999 | 96 |

| 5,000 to 9,999 | 85 |

| ≥ 10,000 | 81 |

Several methotrexate regimens have been studied, including a single-dose protocol, a two-dose protocol, and a multi-dose protocol (Table 4).5 The single-dose protocol carries the lowest risk of adverse effects, whereas the two-dose protocol is more effective than the single-dose protocol in patients with higher initial β-hCG levels.24 There is no consistent evidence or consensus regarding the cutoff above which a two-dose protocol should be used, so clinicians should choose a regimen based on the initial β-hCG level and ultrasound findings, as well as patient preference regarding effectiveness vs. the risk of adverse effects. In general, the single-dose protocol should be used in patients with β-hCG levels less than 3,600 mIU per mL (3,600 IU per L), and the two-dose protocol should be considered for patients with higher initial β-hCG levels, especially those with levels greater than 5,000 mIU per mL. Multidose protocols carry a higher risk of adverse effects and are not preferred.25

| Day | Single-dose regimen | Two-dose regimen |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify baseline stability of complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel; determine β-hCG level Administer single dose of methotrexate, 50 mg per m2 | Verify baseline stability of complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel; determine β-hCG level Administer single dose of methotrexate, 50 mg per m2 |

| 4 | Measure β-hCG level* | Measure β-hCG level Administer second dose of methotrexate, 50 mg per m2 |

| 7 | Measure β-hCG level If decrease from days 4 to 7 is ≤ 15%, offer choice of readministration of single-dose methotrexate, 50 mg per m2, or refer for surgical management; if β-hCG level does not decrease after two doses of methotrexate, refer for surgical management If decrease from days 4 to 7 is > 15%, measure β-hCG levels weekly until they are undetectable | Measure β-hCG level If decrease from days 4 to 7 is ≤ 15%, offer choice of further methotrexate doses or refer for surgical management; further methotrexate doses should be 50 mg per m2 on day 7 with measurement of β-hCG level on day 11, then another dose of 50 mg per m2 on day 11 if β-hCG level does not decrease ≤ 15% from days 7 to 11; if β-hCG level does not decrease ≤ 15% from days 11 to 14, refer for surgical management If decrease from days 4 to 7 is > 15%, measure β-hCG levels weekly until they are undetectable |

Before administering methotrexate, β-hCG levels should be measured on days 1, 4, and 7 of treatment. The first measurement helps the clinician decide between the one- and two-dose protocols. Levels commonly increase between days 1 and 4, but should decrease by at least 15% between days 4 and 7. If this decrease does not occur, the clinician should discuss with the patient whether she prefers to repeat the course of methotrexate or pursue surgical treatment. If the β-hCG level does decrease by at least 15% between days 4 and 7, the patient should return for weekly β-hCG measurements until levels become undetectable, which can take up to eight weeks.26

Close follow-up is critical for the safe use of methotrexate in women with ectopic pregnancies. Patients should be counseled that the risk of rupture persists until β-hCG levels are undetectable, and that they should seek emergency care if signs of ectopic pregnancy occur. It is common for patients to experience some abdominal pain two to three days after administration of methotrexate. This pain can be managed expectantly as long as there are no signs of rupture.5 Gastrointestinal adverse effects (e.g., abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea) and vaginal spotting are common. Patients should be counseled to avoid taking folic acid supplements and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which can decrease the effectiveness of methotrexate, and to avoid anything that may mask the symptoms of ruptured ectopic pregnancy (e.g., narcotic analgesics, alcohol) and activities that increase the risk of rupture (e.g., vaginal intercourse, vigorous exercise). Sunlight exposure during treatment can cause methotrexate dermatitis and should be avoided.5 Other adverse effects of methotrexate include alopecia and elevation of liver enzymes. Patients should be counseled to avoid repeat pregnancy until at least one ovulatory cycle after the serum β-hCG level becomes undetectable, although some experts recommend waiting three months so that the methotrexate can be cleared completely.27 There is no evidence that methotrexate therapy affects future fertility.28

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Overall, surgical management has a higher success rate for ectopic pregnancy than methotrexate.5 The initial β-hCG level at which to transfer a patient for possible surgical treatment depends on local standards, although a level of 5,000 mIU per mL (5,000 IU per L) is commonly used.5,11 Ultrasound visualization of an embryo with fetal cardiac activity outside of the uterus is an indication for urgent transfer for surgical management.5,25 Additionally, social factors that preclude frequent laboratory testing (e.g., poor telephone access, work and family obligations, lack of transportation) can make surgical management the safer option5 (Table 55,11). In cases where methotrexate is contraindicated or not preferred by the patient, surgical management can usually be performed laparoscopically if the patient is hemodynamically stable. Surgical options include salpingostomy or salpingectomy. Randomized trials have shown no difference in sequelae between methotrexate administration and fallopian tube–sparing laparoscopic surgery, including rates of future intrauterine pregnancy and risk of future ectopic pregnancy.29 The decision whether to remove the fallopian tube or leave it in place depends on the extent of damage to the tube (evaluated intraoperatively) and the patient's desire for future fertility.

| Urgent referral Hemodynamic instability Peritoneal signs Ultrasonography shows ectopic pregnancy with fetal cardiac activity Ultrasonography shows substantial fluid in the cul-de-sac and/or beyond |

| Other indications for referral Barriers to close follow-up or refusal to accept blood transfusion High initial β-hCG levels (> 5,000 to 10,000 mIU per mL [5,000 to 10,000 IU per L]) or ectopic pregnancy > 4 cm Insufficient decline in β-hCG levels after administration of methotrexate Medical conditions that preclude medical management with methotrexate (e.g., active peptic ulcer disease, active pulmonary disease, anemia, breastfeeding, clinically important hepatic or renal disease, immunodeficiency, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia) |

EXPECTANT MANAGEMENT

Expectant management can be considered for patients whose peak β-hCG level is below the discriminatory zone and is decreasing, but has plateaued or is decreasing more slowly than expected for a failed intrauterine pregnancy.30 In cases where the initial β-hCG level is 200 mIU per mL (200 IU per L) or less, 88% of patients will have successful spontaneous resolution of the pregnancy; however, rates of spontaneous resolution decrease with higher β-hCG levels.31 Patient counseling must include the risks of spontaneous rupture, hemorrhage, and need for emergency surgery. Patients who choose expectant management should have β-hCG levels monitored every 48 hours, and medical or surgical management should be recommended if β-hCG levels do not decrease sufficiently.5

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Barash, et al.12

Data Sources: An evidence summary from Essential Evidence Plus was reviewed and relevant studies referenced. Additionally, a PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms ectopic pregnancy, first trimester bleeding, and pregnancy of unknown location. The search included meta-analyses, guidelines, and reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Search dates: October 26, 2018, through January 14, 2020.