Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(4):211-220

Related Blog: Guest Post: Providing House Calls During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The demand for house calls is increasing because of the aging U.S. population, an increase in patients who are homebound, and the acknowledgment of the value of house calls by the public and health care industry. Literature from current U.S. home-based primary care programs describes health care cost savings and improved patient outcomes for older adults and other vulnerable populations. Common indications for house calls are management of acute or chronic illnesses, coordination of a post-hospitalization transition of care, health assessments, and end-of-life care. House calls may also include observation of activities of daily living, medication reconciliation, nutrition assessment, evaluation of primary caregiver stress, and the evaluation of patient safety in the home. Physicians can use the INHOMESSS mnemonic (impairments/immobility, nutrition, home environment, other people, medications, examination, safety, spiritual health, services) as a checklist for providing a comprehensive health assessment. This article reviews key considerations for family physicians when preparing for and conducting house calls or leading teams that provide home-based primary care services. House calls, with careful planning and scheduling, can be successfully and efficiently integrated into family medicine practices, including residency programs, direct primary care practices, and concierge medicine.

House calls, also referred to as home visits, are increasing in the United States.1 Approximately 40% of patient visits in the 1930s were house calls.1,2 By 1996, this decreased to 0.5% because insurance reimbursements for house calls decreased.1,2 The pendulum in the United States is swinging again to house calls because of the need to develop care models for the growing aging population.1,3,4 The proportion of house calls to outpatient clinic visits conducted by family physicians in the United States is unlikely to reach the 1930s levels; however, the number of house calls conducted from 1996 to 2016 doubled.3 Medicare Part B billing and reimbursement for house calls are also increasing, with nearly 2.6 million house calls paid in 2015.5

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

House Calls

There were more than 1,100 direct primary care practices in the United States in 2019, and 68% of these practices offered house calls, including eight practices that were completely mobile (i.e., had no actual office).

A systematic review of nine studies (N = 46,156) evaluating home-based primary care outcomes for homebound older adults reported fewer hospitalizations, hospital bed days of care, emergency department visits, long-term care admissions, and long-term bed days.

The increasing popularity of and call for home-based care have led to an increased need to study the outcomes and design of home-based primary care models in the United States. The two largest home-based primary care studies are the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Independence at Home Demonstration and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs home-based primary care program.6,7 The Independence at Home program demonstrated a 23% reduction in hospitalizations, a 27% decrease in 30-day readmissions, and a cost savings of $111 per beneficiary per month, which is a $70 million savings over three years.7–10 Similarly, a large systematic review (N = 46,154; nine studies) evaluating home-based primary care outcomes for homebound older adults reported fewer hospitalizations, hospital bed days of care, emergency department visits, long-term care admissions, and long-term bed days of care.11 The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs home-based primary care study of chronically ill, frail adults (N = 179) in urban populations also found fewer hospital admissions and bed days of care, but no change in emergency department use.12

House calls benefit patients post-hospitalization by reducing readmission rates, associated health care costs, and errors related to transitions of care.13,14 There is an increased need for home-based care for the most vulnerable populations because of the recent shift in the United States toward value-based health care.1,3 In 2011, there were 2 million homebound people in the United States, of which only 12% reported receiving home-based primary care.15 This number is expected to increase to 4 million by 2030.1

House calls also benefit patients with socioeconomic barriers to care, including pregnant patients and children who are at high risk of abuse.16 Nurse- or social worker–led home visiting programs have reduced child maltreatment, decreased child health care overutilization, and improved cognitive skills of children born to a low income household with limited psychological resources.16–18 Outcome data for physician-led house calls are limited for younger populations because most data are from studies on older adults. A meta-analysis of 51 studies of home-based family care reported small, statistically significant improvements in child cognitive outcomes, maternal life outcomes, and parental behaviors and skills.19 Additionally, a Cochrane review of 11,000 newly postpartum patients receiving frequent in-home visits from interdisciplinary teams showed a decrease in infant health service utilization and an increase in maternal interest in exclusive breastfeeding.20

Historically, family physicians have been the workforce that meets the critical needs of the United States' most vulnerable populations. Family physicians need to learn how to incorporate house calls into their practices. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires family medicine residents to conduct house calls.21 Varying the type of calls and including patients with complex needs of all ages add training value that is consistent with the American Academy of Home Care Medicine clinical competencies.22 House calls, with careful planning and scheduling, can be successfully integrated into a busy office-based practice or residency program. Portable technologies, including electronic health records, battery-powered examination equipment, and point-of-care diagnostic testing, enable health care teams to bring office capabilities to patients' homes.1 This article provides tools for conducting house calls and reviews strategies for implementing house calls into a variety of outpatient practices, including residency programs, direct primary care (DPC), and concierge medicine models.

Conditions for the Initiation of House Calls

House calls may be needed for acute reasons because of a change in health status, serial visits for chronic conditions, or a one-time visit requested by caregivers or the physician to evaluate for a specific concern. The type of house call guides the goals and objectives for each patient encounter18 (Table 118,21,23,24). For older adults, consider assessing for geriatric syndromes (e.g., recurrent falls, polypharmacy, frailty, memory loss). Evaluation for suspected elder abuse, neglect, or self-neglect may provide valuable information. Illness or injury prevention house calls for frail, older, homebound adults should focus on preventing functional loss and avoiding hospitalization.18

| Conditions for initiation |

| Patient is homebound (see Table 2) |

| Patient, family member, or member of the home health team requests a house call that is medically necessary, or the patient is willing to pay for a house call |

| Physician needs to negotiate care or clinical decision-making with the patient and caregivers |

| Physician needs to assess the home environment or patient and caregiver interactions |

| Physician needs to verify eligibility for third-party reimbursement for home health services |

| Required family medicine resident education* |

| Types |

| Concierge medicine service |

| Direct primary care visit |

| Family medicine resident education* |

| Family visit (e.g., well-child examinations and immunizations for multiple children; prenatal and postpartum visits) |

| Hospitalization follow-up |

| Illness and injury prevention for patients who are homebound (e.g., immunizations, patient home safety evaluation, strength conditioning, health promotion, disease prevention) |

| Illness management for patients who are homebound (e.g., emergency care, acute care, management of chronic conditions including rehabilitation services and palliative care for any stage of a serious, life-limiting illness) |

| Patient assessment* (e.g., polypharmacy, multiple medical problems, excessive health care use, social isolation, frailty, suspected abuse, suspected neglect or self-neglect, need for family meeting, recent major change in health, consideration for long-term care admission) |

| Patients who are dying (e.g., terminal care, death pronouncement, grief support) |

| Travel medicine |

A patient who is enrolled in Medicare must meet two criteria to be considered homebound (Table 2).25 Most patients who are homebound have chronic medical conditions including heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, or advanced dementia. The goal of the house call for patients who have a chronic illness is to ensure safety at home, prevent exacerbation of symptoms, and evaluate caregiver burden and ability to care for the patient.18 Patients enrolled in Medicare who do not meet homebound criteria for home health care may be eligible for home-based primary care services. These services include hospital-based, veterans affairs–based, or freestanding home-based primary care that provides acute and chronic management of medical conditions, polypharmacy management, improved access to durable medical equipment, community resources for the patient and caregivers, and symptom management in end-of-life care.3 Medical necessity should be documented (i.e., frequently missed appointments, poor medication adherence, high use of emergency department services, or a need to assess function in the home environment).3

| To be eligible for home health services, a Medicare beneficiary must meet both criteria Criterion 1: The patient must either: Because of illness or injury, need the aid of supportive devices such as crutches, canes, wheelchairs, and walkers; the use of special transportation; or the assistance of another person to leave their place of residence or Have a condition such that leaving their home is medically contraindicated If the patient meets one of the criterion 1 conditions, then they must also meet two additional requirements defined in criterion 2. Criterion 2*: There must exist a normal inability to leave home and Leaving home must require a considerable and taxing effort Additionally, the following should not disqualify a person from being considered confined to the home: Participation in therapeutic, psychosocial, or medical treatment in an adult daycare program that is licensed or state certified Any absence of short duration for the purpose of attending a religious service Any absence for the need to receive health care treatment (e.g., ongoing outpatient kidney dialysis, outpatient chemotherapy, outpatient radiation therapy) Any other absence from the home that is infrequent or of relatively short duration For examples of homebound status, see the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual (Chapter 7, §30.1.1) |

For patients reaching the end of life, care focusing on comfort (rather than function or longevity) is a common reason for house calls. Most patients with terminal cancer want to die at home; therefore, home care is a valuable service that helps reduce the likelihood of death in the hospital.18,26–28 House calls made by family physicians for patients who are dying are primarily to provide symptom management such as pain relief for patients not using hospice services, and to provide psychosocial support to the patient and caregivers before death, and to family members and caregivers after the patient's death.29

Preparing for and Conducting House Calls

Previsit planning is essential to ensure the patient's maximum benefit from a house call. A member of the care team should call the patient in advance of arrival to verify the patient's availability and home address. Physicians should review the patient's medical record and medication list in advance, and bring a copy of the most recent information to the house for reconciliation during the visit. Once the physician is at the home, it is important to follow safety precautions (Table 330) to prevent personal injury or infection.18,30 Table 418,31 and Table 518,29,32 list recommended supplies for house calls.

| Ask the patient in advance to cage their pets to avoid the risk of animal bites or other injuries |

| Avoid attracting unwanted attention when arriving and entering the home; consider leaving your white coat and expensive equipment at the office |

| Bring equipment for sharps handling and disposal that is in compliance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration Bloodborne Pathogens Standard |

| Call ahead to remind the patient of the visit; avoid surprising the patient, in particular those with weapons in the home |

| Coordinate house calls with other members of the multidisciplinary care team; alternatively, bring a learner (e.g., medical student, resident, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) or other office member for assistance and to enhance personal security by traveling as a team |

| During the house call, sit on nonclothed furniture, avoid pet droppings, wear gloves or respiratory masks if there is concern for environmental exposure or acute infections; use hand sanitizer before, during, and after the visit |

| Keep other trusted individuals (e.g., office staff members, partners, care team members) informed of the location and appointment time in the event that something does not go as planned |

| Preplan emergency and safety-concern codes (i.e., yes-or-no questions) with another person; these codes should alert that person to send emergency personnel to your location if needed |

| Schedule check-ins with a designated person on arrival and after completion of the visit |

| Travel in a well-maintained vehicle appropriate for anticipated terrain and weather conditions |

| Physician supplies Antibiotic ointment, hydrogel ointment, petroleum jelly Bacterial culture swabs Bandage scissors Batteries (including extra for otoscope, flashlight) Cell phone Cerumen spoons and ear irrigation kit Face mask Flashlight Gauze, tape, packing materials Gloves (sterile and nonsterile) Glucometer, alcohol pads, test strips, lancets Hand sanitizer Lubricant Otoscope or ophthalmoscope Patient address and directions Phlebotomy equipment Pulse oximeter Reflex hammer Sharps container Sphygmomanometer (variety of cuff sizes) Sterile specimen cups Stethoscope Tape measure Thermometer Toenail clippers Tongue depressor Tuning fork | Physician supplies (optional) Catheters Complementary alternative medicine supplies (e.g., acupuncture supplies, osteopathic manipulation table) Device to access electronic health record Dictation software or equipment Disposable bed pads Drug identification and drug-drug interaction checker on smartphone app, computer, or a drug-reference manual Externally worn hearing amplifier Garbage bags or biohazard bags Hazardous materials suit (disposable) including a mask and booties Hemoccult cards and developer Laptop computer with accessories N95 disposable masks Portable electrocardiograph machine Saline flushes, intravenous supplies Silver nitrate sticks Specimen cups Splint or casting materials, crutches, external musculoskeletal brace Suture kit, small forceps, scalpel, staple remover Syringes and needles Vaccines (properly stored) Vaginal speculum Venipuncture supplies Wound care supplies (i.e., sterile and nonsterile gauze, silver impregnated [antibacterial] gauze, iodine impregnated [antibacterial] gauze, methylene blue dressing [antifungal], thin hydrocolloid dressings, staples, sutures, replacement collection bags, tape, wound vacuum supplies, or other supplies based on wound care needs of the patient) | Patient supplies CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) or other home breathing machine Glucometer and glucose testing supplies Home blood pressure monitor Nebulizer Peak flow meter Scale Documentation Advance document preparation (e.g., names, phone numbers, policies, scope of services, advance directives, questionnaires, patient forms) Billing documentation Business and appointment reminder cards Cognitive assessment tools (e.g., Mini-Cog, Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Saint Louis University Mental Status, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Katz Index of Independent Activities of Daily Living, Mini Nutritional Assessment [Nestle Nutrition Institute], Geriatric Depression Scale, Screen for Caregiver Burden, Clinical Assessment of Driving-Related Skills) List of essential community resources and services with websites (e.g., https://www.caregiver.org/family-care-navigator, https://alz.org, https://familydoctor.org, http://www.HealthyAging.org, https://www.aafp.org/afp/handouts/viewAll.htm) Medication reconciliation list Patient record Prescription pad, laboratory slips, radiology forms |

| Condition | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Acute coronary syndrome | Nonenteric-coated aspirin to be chewed Nitroglycerin |

| Agitation and delirium | Risperidone (Risperdal) or haloperidol |

| Allergic reaction | Epinephrine autoinjector |

| Dehydration | Intravenous fluids, infusion set, butterfly needles (21-gauge), tape, occlusive dressing |

| Dyspnea | Benzodiazepine* for subcutaneous or sublingual administration Albuterol inhaler with spacer Opioid† for subcutaneous or sublingual administration |

| Heart failure | Furosemide (Lasix) for subcutaneous administration |

| Hypoglycemia | Glucose tablets, glucagon kit |

| Pain | Opioid† for subcutaneous or sublingual administration |

| Seizure | Benzodiazepine‡ |

| Trauma | Tourniquet for extremity injuries |

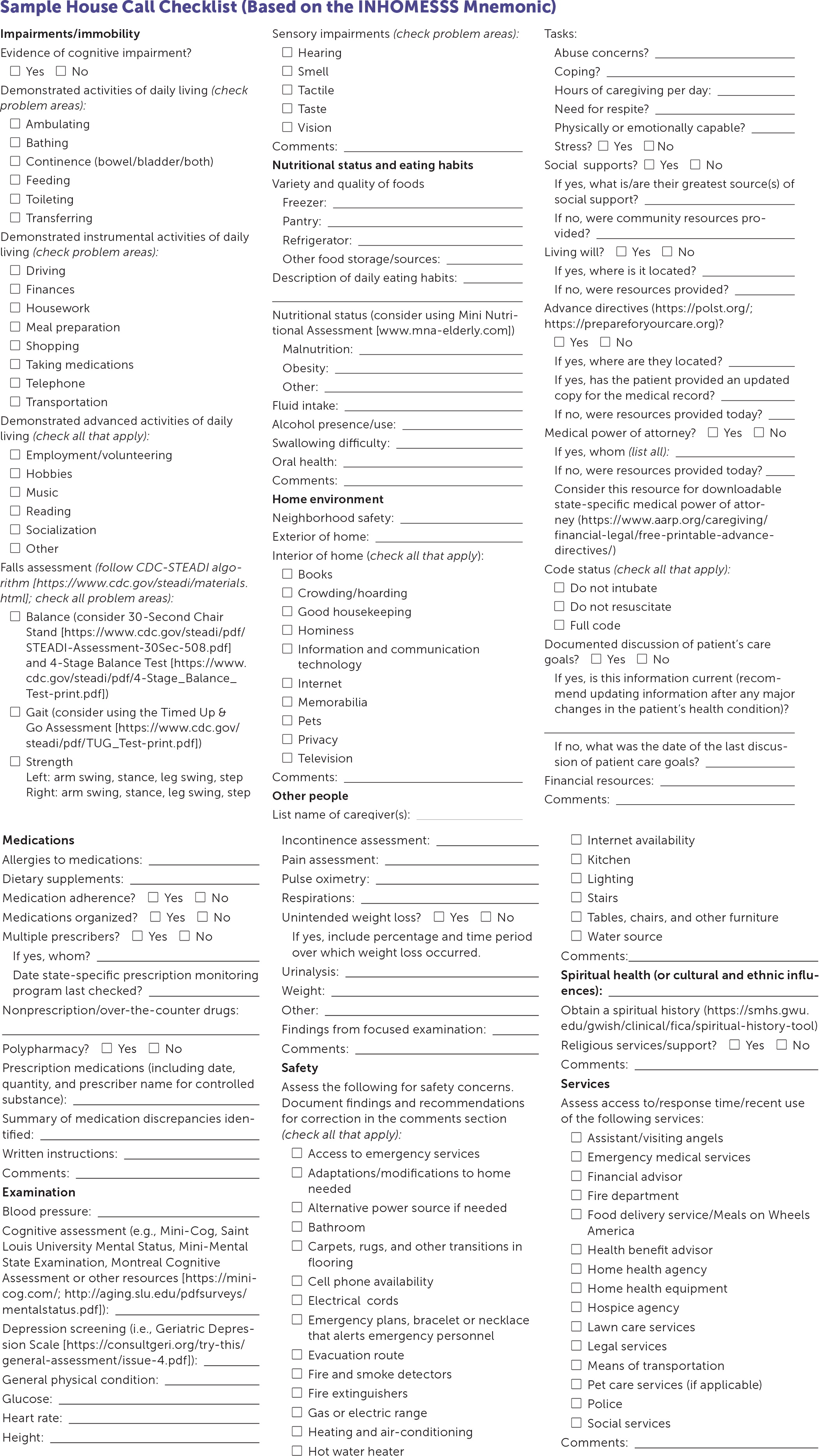

If needed, a house call checklist, such as the INHOMESSS mnemonic (impairments/immobility, nutrition, home environment, other people, medications, examination, safety, spiritual health, services; Figure 1), can be used as a guide for performing a complete geriatric assessment.18 A typical approach begins with observing how the patient enters their home and evaluating for transitions of flooring in entryways and the need for extra grab handles, ramps, or rails. Once inside the home, begin by addressing any urgent patient concerns, then shift the conversation to focus on the items found on the checklist if time permits. This process typically takes 45 to 90 minutes, and frequent breaks are common.

Allocate time to review the patient's prescribed medications, herbs or supplements, and over-the-counter medications. The patient or caregiver should show the physician where these medications are kept and organized to provide further insight into medications that may not have been mentioned, issues with compliance, and identification of stockpiles of old or expired medications. Laying out the medications is recommended to perform true medication reconciliation, in addition to checking for drug-drug interactions.

While the patient is still seated, check vital signs, and perform a focused examination. Once that is completed, the physician should observe the patient as they stand and note if they have difficulty changing positions, need an assistive device to stand (e.g., chair with arms, cane), and how they move around the house (e.g., with a walker, cane, grasping onto furniture). Ask permission to follow the patient through the most frequented areas of the house while observing the patient's gait and noting any balance issues. Looking for transitions in flooring; stairwells; rug placement; pathway obstructions; height of chairs, bed, and toilet; type of showers (walk-in vs. tub); and location of smoke detectors, fire extinguishers, and firearms helps provide an understanding of the patient's functional status and identify potential patient safety and fall hazards (Table 6).18

| Bathroom Are handholds sturdy and in appropriate places? Can the toilet seat be reached? Does the bathtub or shower have a nonslip surface? Is the bathroom floor slick? Drug use Is there evidence of tobacco, alcohol, or other illicit drug use in the home? If yes, is the substance used by the patient or other inhabitant of the home? Electrical cords/appliances Are cords frayed or damaged? Do cords cross walking paths? Emergency actions/evacuation route Are emergency numbers available? Does the patient carry on their person a mode of contacting emergency services (e.g., bracelet or necklace that alerts emergency personnel, cell phone)? Are do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate forms displayed in a location easily spotted by emergency service personnel? Are there means of egress from home? Firearms Are firearms present? If yes, are they secured? (e.g., gun lock, locked case or cabinet, weapon and ammunition separated) Who knows how to access? Fire extinguishers Are fire extinguishers present? If yes, are they accessible and in working order? Is the patient or caregiver able to use them? Heating and air conditioning Are controls accessible and easy to read? Is the home an appropriate temperature year-round? | Hot water heater Is the temperature set below 120°F (49°C)? Kitchen safety (especially gas stoves) Is it easy to tell if a burner is on or open gas flame is present? Does the patient wear loose garments while cooking? Where is food stored? Is the food expired? Lighting and night-lights Is lighting present and sufficient throughout the main living spaces? Loose carpets and throw rugs Are carpets and throw rugs present? If yes, do they need to be secured or removed to prevent falls? Pets Are pets present? If yes, are they easy to care for? If yes, are they likely to be a fall hazard? Smoke detectors and carbon monoxide monitors Are they present? If yes, are they functioning and monitored? Stairs Does the home have external or internal stairs? If yes, are they carpeted and is the carpeting secured? Are the stairs well lit? Are there railings? Are assistive devices (ramps, chairlifts) present or needed? Tables, chairs, furniture Is the furniture sturdy, balanced, and in good repair? Utilities Are the systems monitored and maintained? Water source Is water from a public source or a well? Is the source functioning and safe? |

Provide written safety recommendations to the patient and caregiver addressing all urgent concerns and provide additional comments based on findings from the completed checklist. Some durable medical equipment recommendations, such as hospital beds, may be covered by insurance, including Medicare Part B; however, other equipment, such as grab bars or shower chairs, is not typically covered by insurance. The use of assessment tools (Figure 118) can be incorporated into the house call based on the complexity of the patient's condition, the time allowed, and the purpose of the visit. Having an in-depth discussion of end-of-life care choices, guided by the patient's goals, may be appropriate, even if they have already been addressed in a clinic or hospital setting. End-of-life care choices should be confirmed or readdressed as the patient's health care situation changes. Providing prescriptions, supplies, handouts with helpful websites, or local resources communicates further support to the patient and caregivers.

Incorporating House Calls into Office-Based Practice

The benefits of house calls are substantial for physicians and their patients. Physicians experience a change of pace from typical clinic appointments, and house calls can provide additional important information about the patient, including insight into a patient's actual home situation, medication management, diet, and overall lifestyle. Patients report experiencing peace of mind, increased respect and trust in their physicians, and better access to care after a house call.2,4,33

However, integrating house calls into office-based practice is challenging. Barriers include geography, travel time, and perceived loss of revenue.18 Grouping house calls together within a half-day, grouping locations, and conducting the visits after the conclusion of a clinic day may minimize this barrier. A multidisciplinary strategy for house calls can help decrease physician burden and improve care. The care team commonly includes a customized combination of a physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist, dietician, licensed social worker, clinical pharmacist, licensed practice/vocational nurse, registered nurse, psychiatric nurse, wound care nurse, and nurse practitioners or physician assistants. With a multidisciplinary team, improved tracking and scheduling of patients can optimize time management, allowing for greater spacing and efficiency of physician visits, and can decrease loss to follow-up.

A travel bag, dedicated house call vehicle, and a mobile office are tools that help keep house calls organized. Besides regular office equipment needed for a focused examination and gathering vitals, an emergency supply kit (Table 518,29,32) may be useful. House calls for dying patients are unique because of the symptoms and treatment needs specific to that population. American Family Physician has previously published an article on managing common symptoms in end-of-life care.29 Additional specialized equipment may be necessary based on the patient's needs (Table 418,31). It is important to have a good understanding of patients' individualized needs and commit to goals for the visit in advance. When applicable, physicians should provide educational materials, medication reconciliation forms, do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate forms, out-of-hospital resuscitation forms, home health forms, and hospice-required documents.18

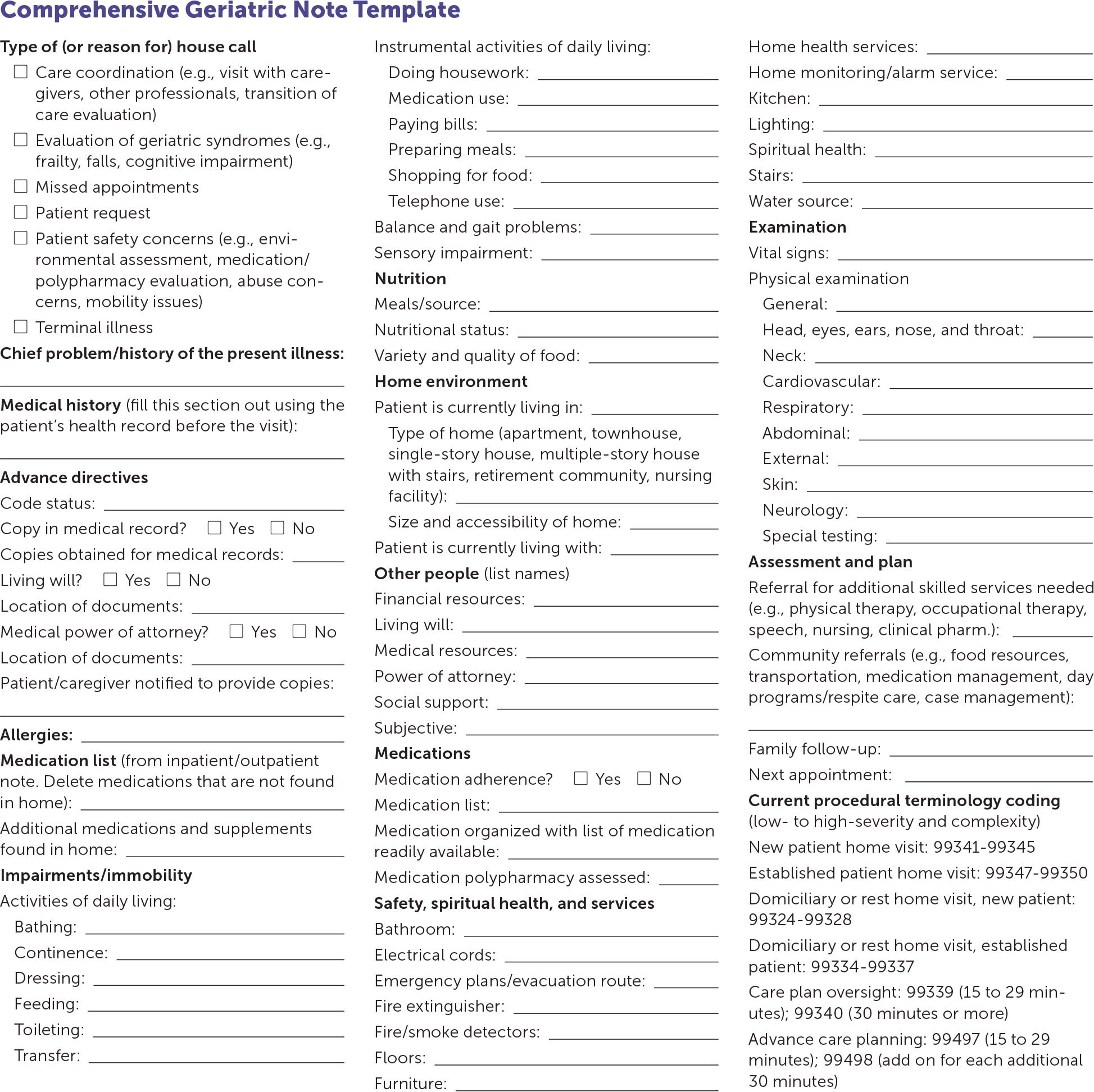

Documentation for a house call is similar to that for an office visit. A note template can help with consistent documentation and serve as a checklist (eFigure A). Recommendations for continued care and changes to the care plan should be included in the documentation with proper coding and billing information (eTable A).

| CPT codes 99341 – 99350 are home service codes used to report evaluation and management services provided to a patient residing in their own private residence (POS code 12). | |

| Home services: new patient | |

| 99341 | Level 1, low severity problem, 20 minutes |

| 99342 | Level 2, moderate severity problem, 30 minutes |

| 99343 | Level 3, moderate to high severity problem, 45 minutes |

| 99344 | Level 4, high severity problem, 60 minutes |

| 99345 | Level 5, patient is unstable or significant new problem requiring immediate attention, 75 minutes |

| Home services: established patient | |

| 99347 | Level 1, self-limited or minor problem, 15 minutes |

| 99348 | Level 2, low to moderate severity problem, 25 minutes |

| 99349 | Level 3, moderate to high severity problem, 40 minutes |

| 99350 | Level 5, patient is unstable or significant, new, high-severity problem requiring immediate attention, 60 minutes |

| CPT codes 99324 – 99337 are domiciliary, rest home, or custodial care services codes and are used to report evaluation and management services provided to patients living in a facility that provides room, board, and other personal assistance services, generally on a long-term basis (POS codes 13, 14, 33, and 55). | |

| Domiciliary (assisted living, group home), rest home, or custodial care visits: new patient | |

| 99324 | Level 1, low severity problem, 20 minutes |

| 99325 | Level 2, low to moderate severity problem, 30 minutes |

| 99326 | Level 3, new patient, moderate to high severity problem, 45 minutes |

| 99327 | Level 4, new patient, high severity problem, 60 minutes |

| 99328 | Level 5, new patient, high complexity problem, 75 minutes |

| Domiciliary (assisted living, group home), rest home, or custodial care visits: established patient | |

| 99334 | Level 1, established patient, self-limited or minor problem, 15 minutes |

| 99335 | Level 2, established patient, low to moderate severity problem, 25 minutes |

| 99336 | Level 3, established patient, moderate to high severity problem, 40 minutes |

| 99337 | Level 4, established patient, unstable or significant new problem, 60 minutes |

| Care plan oversight | |

| 99339 | Supervision of patient requiring complex or multidisciplinary care, 15 to 29 minutes |

| 99340 | Supervision of patient requiring complex or multidisciplinary care, 30 minutes or more |

| Advance care planning evaluation and management services | |

| 99497 | Advance care planning including the explanation and discussion of advance directives such as standard forms, face-to-face with the patient, family members, or surrogate, first 30 minutes, minimum 15 minutes |

| 99498 | Each additional 30 minutes, list separately and in addition to the code for the primary procedure |

| This information applies to public and private health insurance billing for patients of all ages. | |

| The time spent includes telephone calls to other health professionals (not patient family members or caregivers) ordering and reviewing tests. When applicable, document 30 minutes of time spent coordinating care unrelated to a face-to-face visit. | |

| CPT codes for prolonged services should be used in conjunction with time-based companion codes: | |

| 99354, for other outpatient setting, with direct patient contact, first hour. | |

| 99355, for each additional 30 minutes. | |

| Place of service codes | |

| POS 12 | Private residence – patient home, apartment, townhome, etc. |

| POS 13 | Domiciliary care facility – A home providing mainly custodial and personal care for people who do not require medical or nursing supervision, but may require assistance with activities of daily living because of physical or mental disability (e.g., assisted living facility, adult living facility, “sheltered living environment”). |

| POS 14 | Group, rest, or boarding home – A place where people live and are cared for when they cannot take care of themselves. |

| POS 33 | Custodial care facility – Any facility that provides nonmedical assistance with the activities of daily life (e.g., bathing, eating, dressing, using the toilet) for someone who is unable to fully perform those activities without help. |

| POS 55 | Residential substance abuse facility – A facility that provides treatment for substance (alcohol and drug) abuse to live-in residents. |

| Checking with the billing department of a patient's hospice agency for proper documentation and coding tips can help prevent rejected claims. | |

| Home services are billable to home health agencies in the community. A CMC-485 form must be reviewed and signed. | |

| G0180 | Home health certification, $53.00 |

| G0179 | Home health recertification, $44.17 |

| G0181 | Home health care, $104.31 |

| G0182 | Hospice supervision, $105.67 |

| Effective January 1, 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced in the 2019 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule that documenting the medical necessity of a home visit instead of an office visit is no longer needed for billing purposes. | |

Direct Primary Care and Concierge Medicine House Calls

DPC is an innovative practice model that offers patients a variety of primary care services for a low, periodic membership fee.34,35 Integrating house calls into this type of practice may be easier because the DPC model enables physicians to spend more time with patients, and DPC physicians typically have smaller panel sizes. According to Phil Eskew, DO, founder of DPC Frontier, there were more than 1,100 DPC practices in the United States in 2019, and 68% of these practices offered house calls, including eight practices that were completely mobile (i.e., had no actual office). House calls may be included as part of the membership, or DPC physicians may charge a flat rate or a variable amount based on travel time or mileage.36

Although DPC physicians often provide house calls to older adults and to patients who are disabled, terminally ill, and to patients who are homebound, some physicians may also offer newborn visits and well-child examinations. Additionally, house calls are commonly made for sick visits and postoperative care. Large families or families with young children may benefit from house calls because of the convenience and comfort of seeing multiple members at once in a familiar and safe environment. DPC physicians report that offering house calls is useful for recruiting new patients, and families appreciate the home-based service.

Concierge practices also routinely offer house calls but charge higher membership fees and may continue to bill insurance for covered services.37 Concierge practices may also provide hotel calls for travelers seeking more personal, convenient care.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Unwin and Tatum.18

Data Sources: A PubMed search was conducted using the key terms home visits, house calls, home-based primary care, post-hospitalization visits, homebound, and direct primary care. The search included systematic and clinical reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of clinical trials and other primary sources, and evidence-based guidelines. Also searched was the Cochrane database. References from these sources were consulted to clarify the statements made in publications. Search dates: April 2019, August 2019, December 2019, and March 2020.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.