Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(12):737-744

Related FPM article: Durable Medical Equipment: A Streamlined Approach

Related letter: Upright Walkers as Mobility Assistive Devices for Older Adults

Patient information: See related handout on using canes and walkers, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Many individuals need a mobility assistive device as they age. These devices include canes, crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs. Clinicians should understand how to select the appropriate device and size for individual patients (or work with a physical therapist) and prescribe the device using the patient's health insurance plan. Canes can improve standing tolerance and gait by off-loading a weak or painful limb; however, they are the least stable of all assistive devices, and patients must have sufficient balance, upper body strength, and dexterity to use them safely. Older adults rarely use crutches because of the amount of upper body strength that is needed. Walkers provide a large base of support for patients who have poor balance or who have bilateral lower limb weakness and thus cannot always bear full weight on their legs. A two-wheel rolling walker is more functional and easier to maneuver than a standard walker with no wheels. A four-wheel rolling walker (rollator) can be used by higher-functioning individuals who do not need to fully off-load a lower limb and who need rest breaks for cardiopulmonary endurance reasons, but this is the least stable type of walker. Wheelchairs should be considered for patients who lack the lower body strength, balance, or endurance for ambulation. Proper sizing and patient education are essential to avoid skin breakdown. To use manual wheelchairs, patients must have sufficient upper body strength and coordination. Power chairs may be considered for patients who cannot operate a manual wheelchair or if they need the features of a power wheelchair.

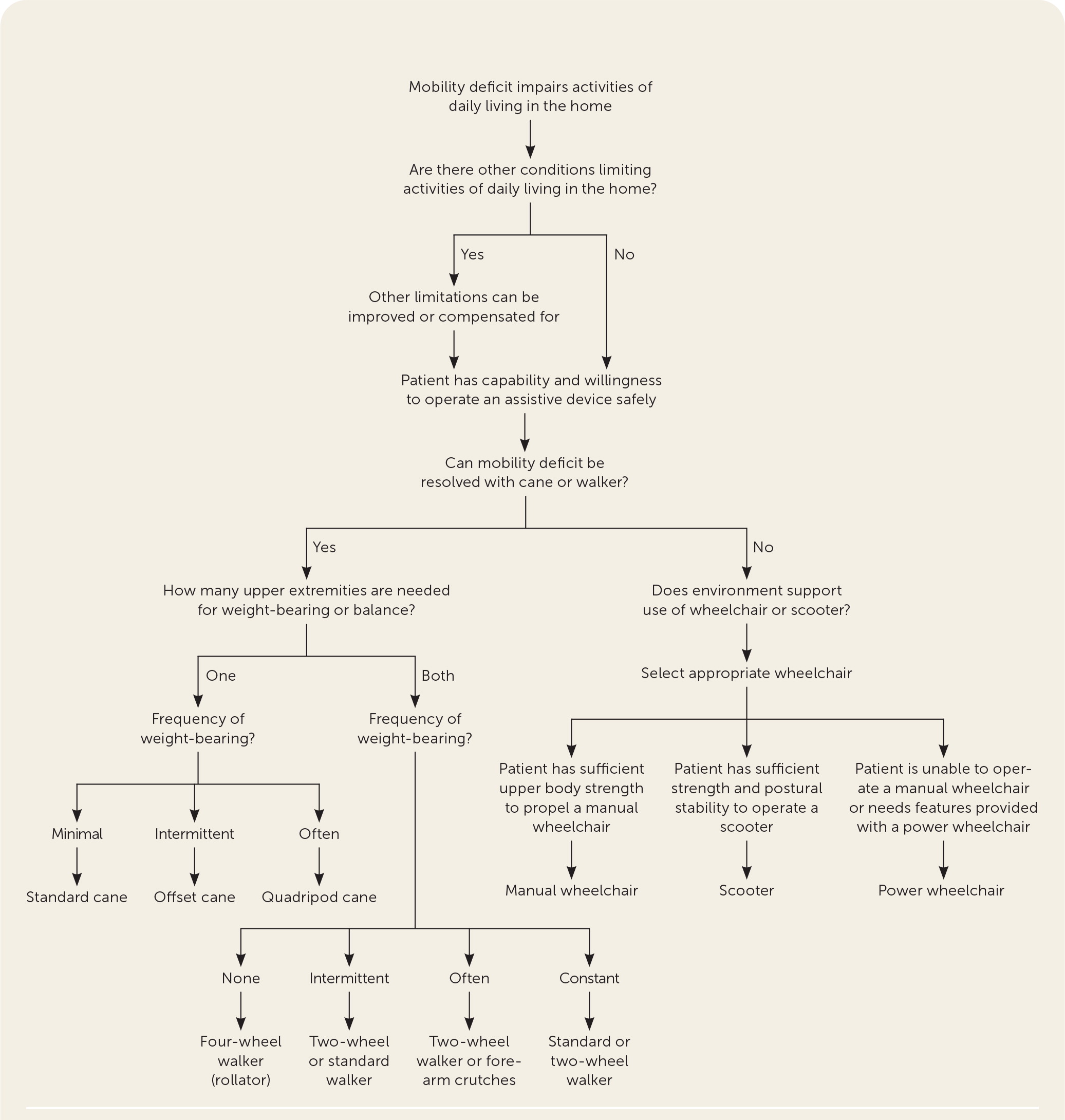

As individuals age, many develop chronic, complex illnesses, including deconditioning, and may need to use a mobility assistive device. Assistive devices such as canes, crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs can help to alleviate the effects of mobility limitations, providing improved independence.1 According to data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study, 29.4% of adults 65 years and older reported using assistive devices within the previous month when outside the home, and 26.2% reported using them inside the home.2 Clinicians should understand how to select the appropriate assistive device (Figure 13–5) and size for individual patients and prescribe the device using the patient's health insurance plan.3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The use of assistive devices can improve balance, reduce pain, increase mobility and confidence, and decrease the risk of falls.9,10 | B | Expert opinion and systematic review of observational studies |

| Because many patients obtain assistive devices without recommendations or instructions from a medical professional, clinicians should evaluate these devices for proper fit and use.13,14 | C | Observational studies and patient surveys on how they use the devices |

| When only one upper limb is needed to aid in balance or weight-bearing, a cane is preferred. If both upper limbs are needed, crutches or a walker is more appropriate.4 | C | Clinical review article |

| Wheelchairs can provide patients with improved mobility and quality of life, but proper sizing and patient education are required to avoid injury to bony prominences and skin breakdown due to seat pressure.5 | C | Expert opinion |

The risk and fear of falling and sustaining an injury increase with age.6 In older adults, falls are associated with morbidity and mortality, worse overall functioning, and early admission to long-term care facilities.6 Clinicians should perform a risk assessment for falls in older patients at least annually.7 Resources on how to prevent falls are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.8

If needed, the use of assistive devices can improve balance, reduce pain, increase mobility and confidence, and decrease the risk of falls.9,10 The correct assistive device can help the patient remain functional for as long as possible and improve their quality of life by increasing independence and the ability to perform activities of daily living.11 These improvements, in turn, may increase the patient's psychological well-being and social engagement. Although assistive devices are thought to prevent falls, they may in fact cause falls if patients do not use them correctly.12 Before prescribing any assistive device, the patient's diagnoses should be considered along with cognitive function, individual goals of care, functional deficits, home environment, and ability to afford the device.11

Mobility assistive devices are covered under Medicare Part D as durable medical equipment (i.e., any equipment used for a medical reason that can withstand repeated use). Durable medical equipment is considered medically necessary when prescribed by a physician for use in a patient's home.11 Durable medical equipment may improve safety and decrease the need for caregiver assistance. Medicare Part B payment for approved durable medical equipment is equal to 80% of the total cost. Patients are responsible for paying their deductible (which may change annually and varies based on insurance plan), then 20% of the total cost.3

Ideally, selection of any assistive device should be tailored to the patient's needs and physical attributes. To avoid deconditioning, clinicians should encourage patients who can ambulate to walk as much as possible and avoid the use of power wheelchairs or scooters. Pros and cons of assistive devices and examples of indicated conditions are summarized in Table 1.4,5

| Device | Pros | Cons | Selected indications for use | Approximate cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canes | ||||

| Standard | Improves balance, most are adjustable | Should not be used for more than minimal weight-bearing; curved handle may be difficult to grasp and may cause carpal tunnel syndrome; may be uncomfortable to use for patients with hand abnormalities; weight-bearing line is behind the cane shaft, which can make it less supportive | Mild ataxia (sensory, vestibular, or visual), mild lower limb arthritis | $10 to $20 |

| Offset | More supportive than a standard cane, appropriate for intermittent weight-bearing, handgrip is more comfortable than a standard cane and puts less pressure on the hand and wrist, most are adjustable | Often used incorrectly (backward) | Moderate lower limb arthritis | $15 to $40 |

| Quadripod | Larger base of support than other canes, can bear more weight, stands on its own, most are adjustable | Slightly heavier than other canes; awkward to use with all four legs on the ground simultaneously; some types may not fit on stairs | Hemiparesis | $15 to $40 |

| Crutches | ||||

| Axillary | Able to off-load 80% to 100% of weight from a lower limb, inexpensive | Difficult to learn how to use, requires substantial energy expenditure and upper body strength, risk of axillary nerve or artery compression, patient unable to use hands while operating | Lower limb fracture or injury | $16 to $30 |

| Platform | Includes a forearm pad that can be used to bear weight rather than the hand | Difficult to learn how to use | Wrist fracture, rheumatoid arthritis | $75 to $100 |

| Forearm (Lofstrand) | Forearm cuff and handpiece used for weight-bearing; frees hands without having to drop crutch; less cumbersome to use, particularly on stairs | Permits only occasional weight-bearing | Cerebral palsy, paraparesis | $40 to $100 |

| Walkers | ||||

| Standard walker (no wheels) | Most stable walker, folds easily | Needs to be lifted up with each step; slower, less natural gait | Severe myopathy or neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, lower limb fractures | $20 to $60 |

| Two-wheel rolling walker | Maintains normal gait pattern, does not need to be lifted up with each step | Large turning arc, less stable than standard walker | Lower limb arthritis, pain, or injury; poor balance; severe myopathy or neuropathy; paraparesis; parkinsonism | $35 to $60 |

| Four-wheel rolling walker (rollator) | Easy to propel; highly maneuverable, with small turning arc; typically has a seat for resting and a basket | Should not be used for weight-bearing, less stable than two-wheel walker, does not fold easily | Generalized decreased endurance, spinal stenosis, moderate lower limb arthritis, lung disease, congestive heart failure | $50 to $100 |

| Manual | Improved long-distance mobility, complete off-loading of both lower limbs | Requires substantial energy expenditure and upper body strength, may cause injury to bony prominences and skin breakdown due to seat pressure | End-stage disease, severe lower limb arthritis, frailty, paraplegia | $100 to $200 |

| Power | Improved mobility and activities of daily living for those with severe disability | Powered by battery that needs to be charged, manual wheelchair needed for use during power outages or emergencies | End-stage disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, frailty, quadriplegia | $1,000 to > $2,500 |

Canes

A cane is the least restrictive assistive device but is also the least stable. An individual must have sufficient balance, upper body strength, and dexterity to use a cane. Canes can improve standing tolerance and gait by partially off-loading a weak or painful limb, enhancing the base of support, and improving sensory feedback from the ground. Canes can off-load approximately 10% of the weight from an affected lower limb if used properly.

The cane should be held on the contralateral side of the weak or painful lower limb and advanced simultaneously with the impaired limb. Many canes can be adjusted to fit a patient's height. The top of the cane handle should be at the level of the wrist of an arm hanging by the patient's side. The standing patient should have 20 to 30 degrees of elbow flexion when holding the cane on the ground and positioned as vertically as possible.5

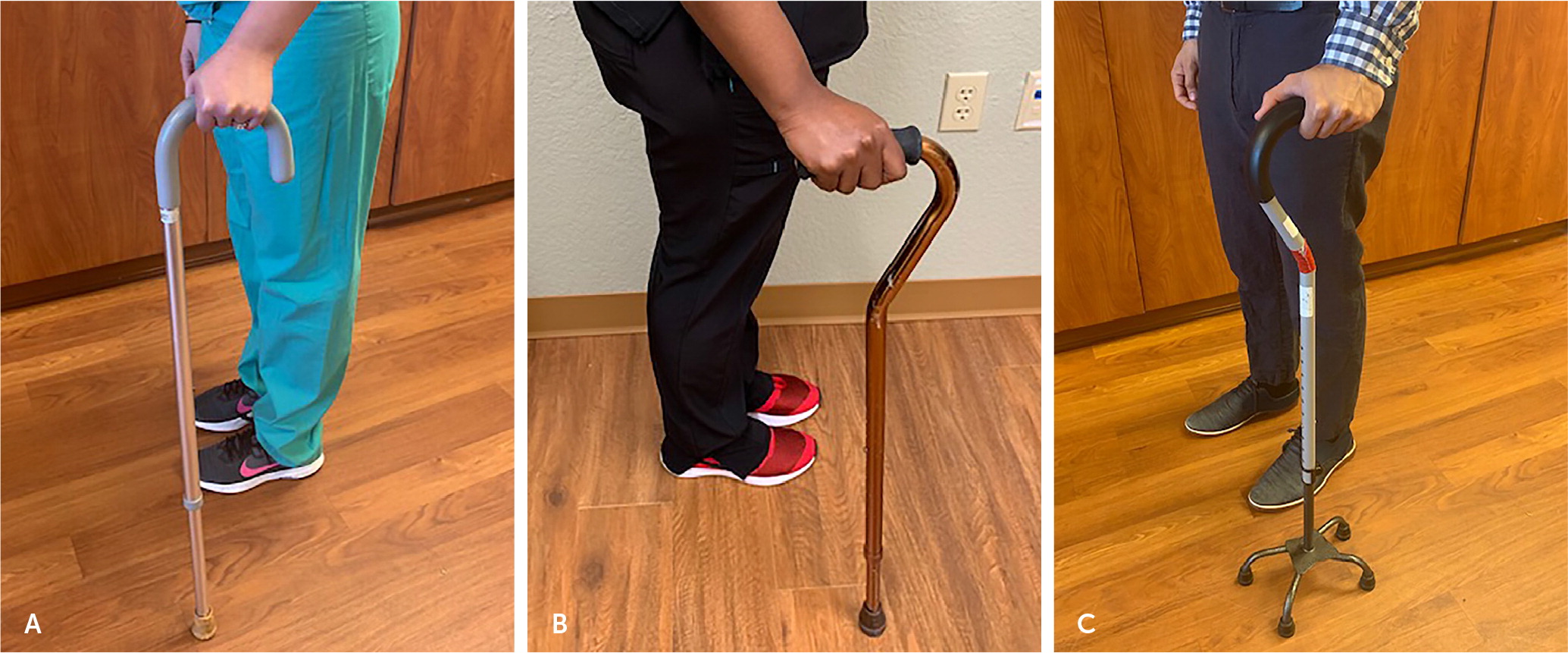

STANDARD CANE

OFFSET CANE

The function of an offset cane is similar to the standard cane, but the handle has a straight grip with an offset angle so that the weight-bearing line goes straight down through the cane shaft (Figure 2B). This weight-bearing alignment improves support and balance, and the handgrip is more comfortable for most patients than the standard cane. An offset cane is often more expensive than a standard cane.5

QUADRIPOD CANE

A quadripod cane has a larger base of support than standard and offset canes (Figure 2C). Its four legs provide better stability and increased weight-bearing through the upper limbs. The quadripod cane can stand on its own and may have a small or large base depending on the amount of support the patient needs.5

Crutches

A cane has only one point of contact with the body (the hand), whereas crutches have multiple points of contact (the axilla and hand). Crutches can be helpful for patients who require higher levels of weight off-loading than canes can provide.

Bilateral crutches can off-load 80% to 100% of weight from a lower limb, and most are adjustable for patient height. However, crutches require sufficient upper body strength, stability, and range of motion, and both hands are needed. The use of crutches also increases metabolic demands.5 For these reasons, crutches are rarely used in older adults.

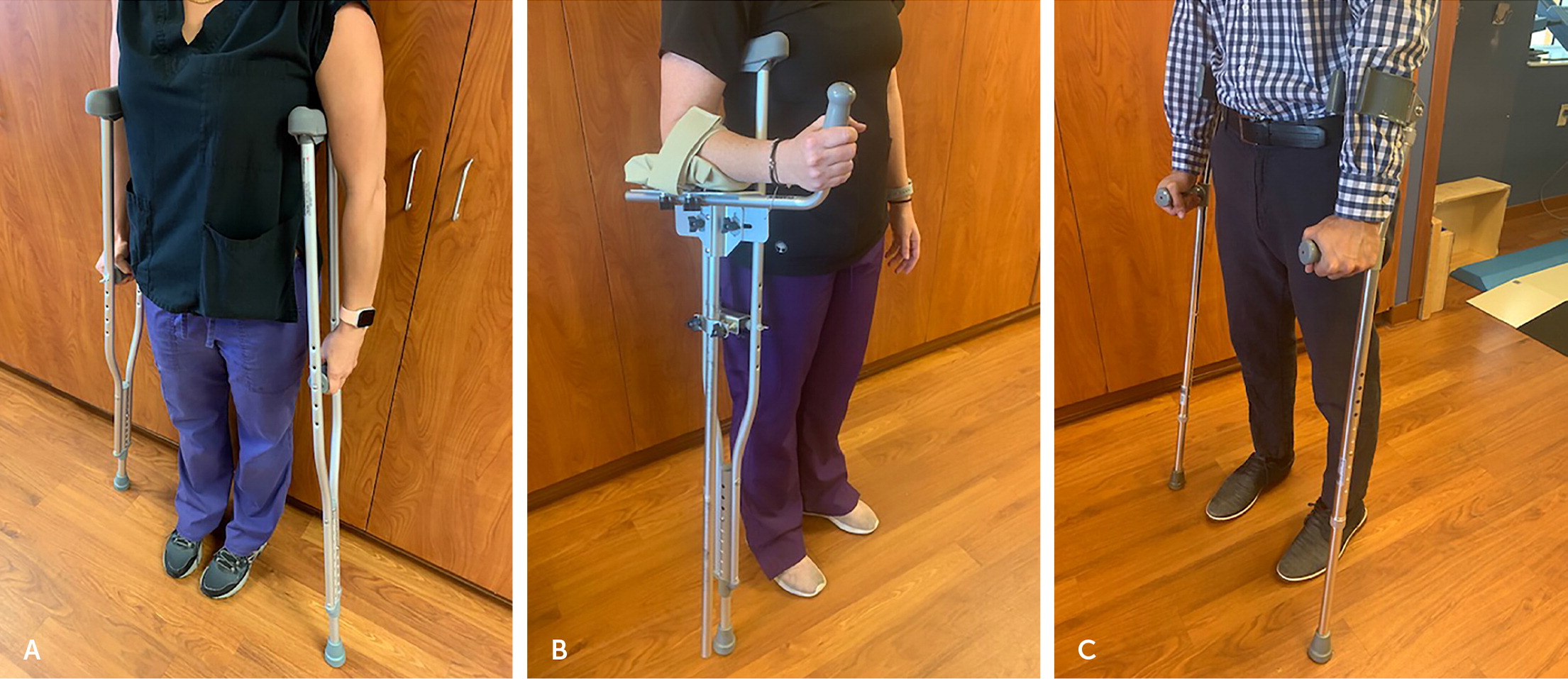

AXILLARY

Axillary crutches are inexpensive and can partially or fully off-load a lower limb. The crutches have a padded top that fits in the axilla to assist with control of the device and a handle for the hands to apply weight (Figure 3A). Body weight should not be applied to the top pad because this can cause axillary nerve and artery compression. To avoid this, there should be a 1.5- to 2-inch gap between the top pad of the crutch and the axilla.5

PLATFORM CRUTCHES

A platform crutch is an axillary crutch with an attached horizontal forearm pad that allows for weight-bearing through the forearm5 (Figure 3B). These crutches provide more stability than standard axillary crutches and can be useful for individuals who have a weak handgrip. However, platform crutches have less maneuverability and are not commonly used.15

FOREARM CRUTCHES

Forearm crutches, also known as Lofstrand crutches, use a forearm cuff with a narrow opening and a handpiece for weight-bearing (Figure 3C). The forearm cuff should be 2 inches below the elbow, and the height of the handpiece should be adjusted for 20 to 30 degrees of elbow flexion. These crutches are lightweight, are easily adjustable, allow better hand freedom than axillary crutches, and are often preferred to standard axillary crutches for long-term use.15 However, they require high levels of upper body strength and trunk balance.5

Walkers

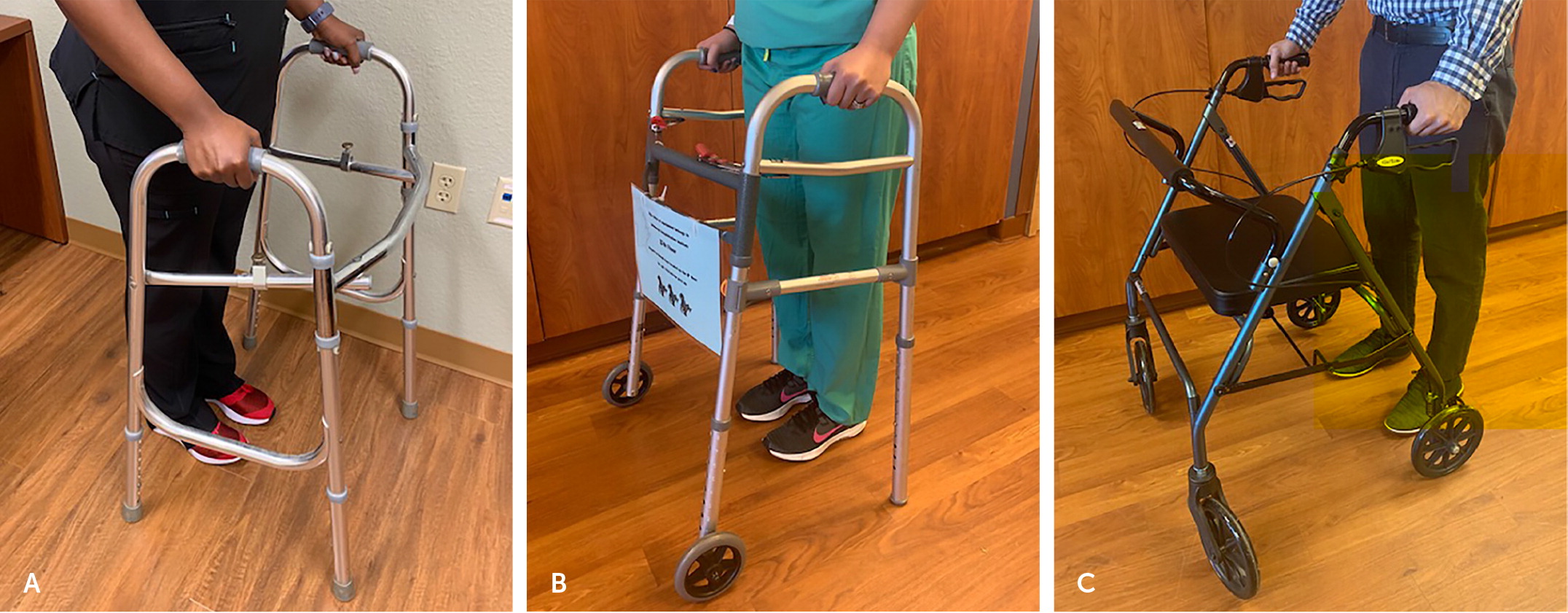

Walkers provide a large base of support for patients who have poor balance or who have bilateral lower limb weakness and thus cannot always bear full weight on their legs. Most walkers have four legs with adjustable heights. Walkers can be difficult to maneuver, require upper-body strength and the ability to bear at least partial body weight, and can promote poor spine mechanics if not used properly.5

STANDARD WALKER (NO WHEELS)

A standard walker is the most stable, with four legs that have rubber tips to reduce slipping (Figure 4A). The patient must completely lift the walker for any movement, which requires sufficient upper body strength and balance. The standard walker substantially slows the patient's gait but provides good support and stability.5

ROLLING WALKER (TWO WHEELS)

A two-wheel rolling walker has wheels on the front legs and sliders or rubber tips on the back legs (Figure 4B). It is more functional and easier to maneuver than a standard walker, allowing patients without good upper body strength to move without lifting the walker and to maintain a more normal gait. The back legs provide some friction to inhibit the walker from sliding away.5

ROLLING WALKER (FOUR WHEELS)

The four-wheel rolling walker, also known as a rollator, has wheels on all four legs (Figure 4C). It is the least stable type because it can slide out from under a patient when the handle brakes are not engaged. Many have a seat and basket, which are convenient for rest breaks and carrying items. Four-wheel rolling walkers are appropriate for higher-functioning individuals who need no weight-bearing support and who need rest breaks for cardiopulmonary endurance reasons.5

Wheelchairs

Wheelchairs should be considered for patients who do not have the lower limb strength, balance, or endurance needed for ambulation. Wheelchairs can provide patients with improved mobility and quality of life, but proper sizing and patient education are required to avoid injury to bony prominences and skin breakdown due to seat pressure.5

Many wheelchairs have an antitipping feature so that the chair cannot fall backward when in use. In addition, most components of wheelchairs can be customized to fit the patient, including legrests; armrests; and back angle, width, and height. Ultralight versions are available and are easier to pick up. Many chairs can be folded to fit into the trunk of a car. Wheelchairs are covered by Medicare only if the patient needs it to perform activities of daily living in their home.3,5

The wheelchair that best complements a patient's functional capacity should be chosen and fitted correctly. Some communities have wheelchair clinics run by a physician and therapy team with experience in choosing and sizing wheelchairs. These clinics also can assist with choosing the proper seat cushion to avoid pressure injury to the skin and to assist with comfort. Patients may benefit from consultation with a physiatrist, physical therapist, or other clinician with knowledge in proper wheelchair selection.

MANUAL

Manual wheelchairs have large back wheels with hand-rails for propelling the chair (Figure 5). Propelling a manual wheelchair takes slightly more energy than ambulation and requires upper body strength and coordination. A companion or transport wheelchair has four small wheels, is lighter, requires another person to push it, and folds to fit into the trunk of a car.5

POWER

Power wheelchairs do not require a person to propel them. They are appropriate for patients who do not have the upper body strength or endurance to self-propel a manual wheel-chair. Power wheelchairs have many variations. For example, some have seats that can be elevated to reach higher objects, and some can be operated with hand, foot, or mouth controls (such as for a patient who is quadriplegic). Power wheelchairs are powered by batteries that have to be charged. A patient with a power wheelchair should have a manual wheelchair available for use during power outages or emergencies.5

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Bradley and Hernandez,4 and Van Hook, et al.16

Data Sources: A Medline search was completed using PubMed. Key terms were assistive devices, canes, crutches, walkers, and wheelchairs. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and review articles. Also searched were the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, Agency for Health-care Research and Quality evidence reports, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website, and amazon.com. Search dates: February to March 2020, and February 19, 2021.