Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):589-597

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Septic arthritis must be considered and promptly diagnosed in any patient presenting with acute atraumatic joint pain, swelling, and fever. Risk factors for septic arthritis include age older than 80 years, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, recent joint surgery, hip or knee prosthesis, skin infection, and immunosuppressive medication use. A delay in diagnosis and treatment can result in permanent morbidity and mortality. Physical examination findings and serum markers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, are helpful in the diagnosis but are nonspecific. Synovial fluid studies are required to confirm the diagnosis. History and Gram stain aid in determining initial antibiotic selection. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common pathogen isolated in septic arthritis; however, other bacteria, viruses, fungi, and mycobacterium can cause the disease. After synovial fluid has been obtained, empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated if there is clinical concern for septic arthritis. Oral antibiotics can be given in most cases because they are not inferior to intravenous therapy. Total duration of therapy ranges from two to six weeks; however, certain infections require longer courses. Consideration for microorganisms such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Borrelia burgdorferi, and fungal infections should be based on history findings and laboratory results.

Septic arthritis should be considered in adults presenting with acute monoarticular arthritis. A delay in diagnosis and treatment of septic arthritis can lead to permanent morbidity and mortality. Subcartilaginous bone loss, cartilage destruction, and permanent joint dysfunction can occur if appropriate antibiotic therapy is not initiated within 24 to 48 hours of onset.1 The reported incidence of septic arthritis is four to 29 cases per 100,000 person-years, and risk increases with age, use of immunosuppressive medications, and lower socioeconomic status.2

Intra-articular infection is typically monoarticular, with up to 20% of cases occurring in multiple joints (oligoarticular [also called polyarticular]).1,3 A joint is most commonly infected hematogenously from bacteremia. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus species are the most common causes. Septic arthritis is diagnosed through laboratory testing, particularly synovial fluid studies.

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

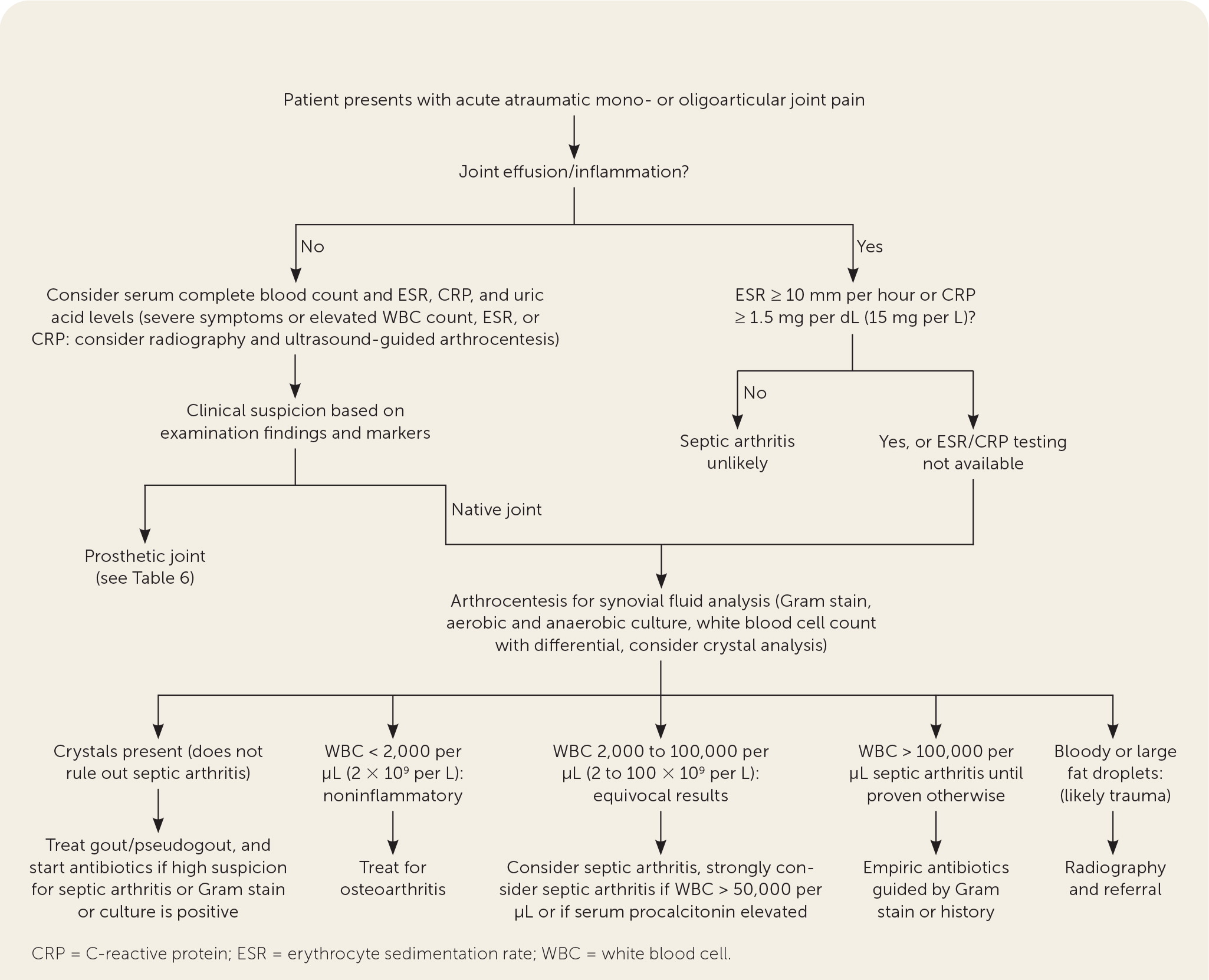

The presentation of septic arthritis may vary based on pathogen, underlying medical conditions, or exposures (Table 1).1,2,4–7 Septic arthritis may present similarly to other types of arthritis. More than 50% of patients with septic arthritis have a history of joint swelling, joint pain, and fever. Sweats or rigors are less common. Native joint infections most commonly occur in the knee, followed by the hip, shoulder, ankle, elbow, and wrist.1 Patients with septic arthritis may present with an acutely painful atraumatic joint, which should be differentiated from other causes of monoarticular joint pain (Figure 18–10 and Table 21 ).

| Clinical history or exposure | Joint involvement | Pathogen |

|---|---|---|

| Cleaning fish tank | Small joints (fingers, wrists) | Mycobacterium marinum |

| Dog or cat bite | Small joints (fingers, toes) | Capnocytophaga species, Pasteurella multocida |

| Exposure to soil or dust containing decomposed wood (North Central and Southern United States) | Monoarticular; knee, ankle, or elbow | Blastomyces dermatitidis |

| Ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products | Monoarticular, sacroiliac joint | Brucella species |

| Intravenous drug abuse | Axial joints, such as sternoclavicular or sacroiliac joint | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus |

| Nail through shoe | Foot | P. aeruginosa |

| Older age | — | Increased risk of gram-negative infections |

| Prosthetic joint | Any prosthetic joint | Coagulase-negative staphylococci, Pseudomonas species, Pneumococcus species |

| Sexually active | Tenosynovial component in hands, wrists, or ankles | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

| Soil exposure/gardening | Monoarticular; knee, hand, or wrist | Nocardia species, Pantoea agglomerans, Sporothrix schenckii |

| Southwestern United States, Central and South America (primary respiratory illness) | Knee | Coccidioides immitis |

| Underlying medical conditions | ||

| Diabetes mellitus or immunocompromise | — | Increased risk of fungal infection (most commonly Candida), Pseudomonas, and Escherichia coli |

| Gout | — | Increased risk of Pseudomonas and E. coli |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Oligoarticular (also called polyarticular) | Increased risk of fungal (most commonly Candida) and pneumococcus infections |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (particularly with functional hyposplenism) | — | N. gonorrhoeae, Proteus species, Salmonella species |

| Terminal complement deficiency | Tenosynovial component in hands, wrists, or ankles | N. gonorrhoeae |

| Diagnosis | Etiology |

|---|---|

| Crystal-induced arthritis | Calcium oxalate, cholesterol, gout, hydroxyapatite crystals, pseudogout |

| Infectious arthritis | Bacteria, fungi, mycobacteria, spirochetes, viruses |

| Inflammatory arthritis | Behçet syndrome,* rheumatoid arthritis,* sarcoidosis, seronegative spondyloarthropathy (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease), Still disease,* systemic lupus erythematosus,* systemic vasculitis* |

| Osteoarthritis | Erosive/inflammatory variants* |

| Systemic infection | Bacterial endocarditis, HIV infection |

| Tumor | Metastasis, pigmented villonodular synovitis |

| Other | Amyloidosis, avascular necrosis, clotting disorders/anti-coagulant therapy, familial Mediterranean fever,* foreign body, fracture, hemarthrosis, hyperlipoproteinemia,* meniscal tear |

Oligoarticular septic arthritis is more likely to present with symptoms of systemic infection and more commonly affects the shoulder, wrist, and elbow.11 Bacteremia is especially common with septic arthritis of the shoulder.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for septic arthritis are listed in Table 3.1,11 Patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a flare-up in one or multiple joints are at particularly high risk. In one study, the incidence of septic arthritis was 1.8 per 1,000 patient-years in those treated with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs vs. 4.2 per 1,000 patient-years in those treated with anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy.12 People who smoke tobacco also have an increased risk of septic arthritis.2

| Contiguous spread |

| Skin infection, cutaneous ulceration |

| Direct inoculation |

| Previous intra-articular injection |

| Prosthetic joint (within two years) |

| Recent joint surgery |

| Hematogenous spread |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| HIV infection |

| Immunosuppressive medication use |

| Intravenous drug abuse |

| Osteoarthritis |

| Other causes of sepsis |

| Prosthetic joint (more than two years) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Sexual activity (gonococcal arthritis) |

| Other |

| Age older than 80 years |

| Smoking |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination of patients with septic arthritis almost always reveals a severely painful joint with motion, often including an obvious effusion. The presentation is typically more subtle in those with periprosthetic joint infections, small joint infections, atypical infections (e.g., fungal, Lyme disease, tuberculosis), or immunosuppression. An overlying skin infection can be the source of pain or the entry point of the intra-articular infection.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Serum markers may be helpful in evaluating for septic arthritis but are not diagnostic. A 2011 study showed that serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level are each more than 90% sensitive for septic arthritis when low cutoffs are used (98% for ESR of 10 mm per hour or greater, 94% for ESR of 15 mm per hour or greater, and 92% for CRP of 2.0 mg per dL [20 mg per L] or greater), which is helpful in ruling out septic arthritis.8 A 2017 meta-analysis showed that with a cutoff of 0.5 ng per mL or greater, procalcitonin has a higher specificity than CRP (95% CI, 0.87 to 0.98; positive likelihood ratio = 10.97).13 Blood cultures should be considered when bacteremia or fungemia is suspected.

Analysis of synovial fluid obtained via arthrocentesis is necessary to differentiate septic arthritis from other forms of arthritis and to determine the causative pathogen.1,4 Synovial fluid analysis should include Gram stain, aerobic and anaerobic cultures, and white blood cell count with differential (Table 41,14–16).

| Arthritis diagnosis | Color | Transparency | Viscosity | WBC count (per μL [× 109 per L]) | PMN cell count (%) | Gram stain | Culture | PCR test | Crystals | Multiplex PCR test* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Clear | Transparent | High/thick | < 200 (0.20) | < 25 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Noninflammatory | Straw | Translucent | High/thick | 200 to 2,000 (0.20 to 2) | < 25 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Inflammatory | ||||||||||

| Crystalline disease | Yellow | Cloudy | Low/thin | 2,000 to 100,000 (2 to 100) | > 50 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Noncrystalline disease | Yellow | Cloudy | Low/thin | 2,000 to 100,000 | > 50 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Infectious | ||||||||||

| Lyme disease | Yellow | Cloudy | Low | 3,000 to 100,000 (3 to 100) | > 75 | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive |

| Gonococcal | Yellow | Cloudy-opaque | Low | 34,000 to 68,000 (34 to 68) | > 75 | Variable (< 50%) | Positive (25% to 70%) | Positive (> 75%) | Negative | Positive |

| Nongonococcal | Yellow-green | Opaque | Very low | > 50,000 (50); > 100,000 is more specific, < 50,000 is common in atypical infection and periprosthetic joint infection | > 75 | Positive (60% to 80%) | Positive (> 90%) | — | Negative† | Positive |

A white blood cell count less than 50,000 per μL (50 × 109 per L) does not exclude septic arthritis.1,14,15 Crystal analysis is appropriate if crystalline arthritis is suspected, but the presence of crystals does not exclude septic arthritis.1,4 Elevated levels of white blood cells and CRP in synovial fluid are common in both crystalline arthritis and septic arthritis.8–10 A synovial biopsy may be needed if synovial fluid findings are negative and suspicion for septic arthritis remains.4

Other laboratory tests are being investigated for use in the diagnosis of septic arthritis. Synovial fluid lactate may be useful in differentiating septic arthritis from other types of acute arthritis, but data are limited.17 A calprotectin measurement at a threshold of 50 mg per L or greater may also be useful for making the diagnosis.17 In addition, multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing may be at least as effective as synovial fluid culture in diagnosing septic arthritis but with a shorter turnaround time (within five hours).15

IMAGING

No imaging finding is pathognomonic for septic arthritis in adults. Plain radiography establishes a baseline and can evaluate for fractures. Ultrasonography can guide arthrocentesis for inaccessible joints, such as the hips, and small joints. Magnetic resonance imaging, preferably with and without contrast, is useful in assessing for osteomyelitis and soft tissue infections.1,18

ORGANISMS

In adults, S. aureus is the most common cause of native joint septic arthritis, followed by Streptococcus species. Native joint septic arthritis can be associated with some viral infections, including chikungunya, rubella, and parvovirus B19. Methicillin-sensitive S. aureus infection is a common cause of oligoarticular arthritis, and group B streptococci are more common in oligoarticular arthritis than in monoarticular septic arthritis.1,4 In older people, gram-negative bacteria, especially Escherichia coli, cause about 23% to 30% of septic arthritis cases.11 In adolescents and young adults, Neisseria gonorrhoeae should be considered.

Management

| Gram stain result | Antibiotics |

| Empiric antibiotics based on Gram stain result | |

| Gram-positive cocci | Vancomycin or daptomycin (Cubicin), plus a cephalosporin, carbapenem, or fluoroquinolone |

| Alternative: oral clindamycin plus fluoroquinolone | |

| Gram-negative cocci | Ceftriaxone |

| Gram-negative rods | Ceftazidime (Fortaz), cefepime, piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), or carbapenem |

| Penicillin or cephalosporins allergy: IV aztreonam (Azactam) or IV fluoroquinolone | |

| Negative result on Gram stain but strong clinical suspicion for septic arthritis | Vancomycin plus ceftazidime or an aminoglycoside |

| Isolated species | Antibiotics |

| Antibiotics based on culture, acid-fast stain, RNA probe, or antibody findings | |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Oral doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime; IV ceftriaxone if no resolution after oral therapy |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Rifampin, often with a multidrug regimen (in consultation with an infectious disease specialist) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | IV ceftriaxone or cefotaxime; switch to oral after 2 days, following antimicrobial susceptibility testing and substantial clinical improvement, for at least 7 days total |

Antibiotics should initially cover gram-positive cocci because they are most common (in particular Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species). Gram-negative coverage should be considered for patients with other risk factors, such as older age, immunosuppression, or bacteremia from a urinary or gastrointestinal source. Treatment should be individualized according to clinical response and microbiology results.11

Oral antibiotics were not inferior to intravenous antibiotics when started within one week of surgery or arthrocentesis and intravenous therapy in a study evaluating the first six weeks of therapy and treatment failures within one year.25 Clindamycin-based therapy appears to be a safe, effective alternative to the traditional regimen of vancomycin or daptomycin (Cubicin) plus a cephalosporin, carbapenem, or fluoroquinolone, especially when it is combined with fluoroquinolones. Clindamycin-based therapy also allows direct conversion from intravenous to oral therapy.23

Optimal duration of treatment for nongonococcal septic arthritis is uncertain but is at least two weeks for small joints; at least six weeks is more commonly prescribed for all joints.2 One randomized trial showed that after surgical lavage, two weeks of antibiotic therapy is not inferior to four weeks of antibiotic therapy.28 However, because most cases in the study involved the hand and wrist, the researchers cautioned against applying the findings to septic arthritis affecting other joints.

Septic arthritis caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus requires drainage or debridement and three to four weeks of antibiotics. Parenteral options include intravenous vancomycin and daptomycin. Parenteral and oral options include trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole with rifampin, linezolid (Zyvox), and clindamycin, but there is no specific guidance regarding the duration of intravenous therapy before initiation of oral therapy.7

Prognosis

A large cohort study showed that the 90-day mortality rate for septic arthritis is 7% and increases to 22% to 69% in patients 80 years and older.29 Other comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, bacteremia, and low creatinine clearance are also associated with increased mortality.30 Oligoarticular septic arthritis is associated with higher mortality compared with monoarticular septic arthritis.11 Septic arthritis affecting small native joints has a better prognosis and may require a shorter duration of antibiotic therapy than large native joints.2 Poor functional outcomes such as amputation, arthrodesis, prosthetic surgery, and severe functional deterioration occur in about 24% to 33% of patients with septic arthritis and are more likely with older age, preexisting joint disease, and synthetic intraarticular material.2

Special Considerations

GONOCOCCAL ARTHRITIS

Gonococcal arthritis is caused by bacteremia from a sexually transmitted N. gonorrhoeae infection. Two forms of disseminated gonococcal infection that present with arthritis are localized septic arthritis and an arthritis-dermatitis syndrome that is characterized by malaise, polyarthralgias, tenosynovitis, and dermatitis.31,32 Gonococcal arthritis can present as a monoarthritis, oligoarthritis, or polyarthritis and affect any joint.33

If gonococcal septic arthritis is suspected, polymerase chain reaction testing of potentially infected mucosal sites, such as the urethra, rectum, pharynx, and cervix, should be performed.19 If gonococcal arthritis is confirmed, further evaluation for sexually transmitted infections is recommended.

LYME ARTHRITIS

Lyme arthritis can be monoarticular or oligoarticular and intermittent or persistent, and it typically affects the knee. It is the most common manifestation of disseminated Lyme disease in the United States.34 Fever is less common with Lyme arthritis than with other causes of septic arthritis. Among patients with Lyme arthritis, 10% to 20% will have persistent symptoms, including joint pain, after appropriate antibiotic therapy.35,36

Serum antibody testing is recommended first (with an estimated 96% sensitivity and 94% specificity). If positive, polymerase chain reaction testing of synovial fluid should be performed.16,24,37 Polymerase chain reaction testing of synovial fluid is nearly 100% sensitive and 42% to 100% specific for Lyme arthritis.16

TUBERCULOSIS ARTHRITIS

Mycobacterial joint infections are more indolent than other bacterial joint infections, and it can take months to years for symptoms such as recurrent joint effusions to manifest. In addition, a patient with a mycobacterial joint infection may not have radiologic evidence of pulmonary involvement.40

FUNGAL ARTHRITIS

The presentation of fungal infections varies significantly. Many infections are indolent in presentation, whereas some cause rapid destruction.22 Risk factors for fungal arthritis include diabetes, HIV infection, immunosuppression from disease or medication use, organ transplantation, parenteral hyperalimentation, indwelling catheter, substance abuse, and use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.41 Candida is the most common pathogen causing fungal septic arthritis, although it is normal flora found on the skin and mucous membranes of healthy individuals. Other species that can cause fungal septic arthritis include Aspergillus, Coccidioides, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, and Cryptococcus. It is best to manage fungal septic arthritis in coordination with orthopedic surgery and infectious disease specialists.

PERIPROSTHETIC JOINT INFECTION

Periprosthetic joint infection is becoming a more common presentation in primary care because of increasing numbers of joint replacement surgeries performed each year. The projected number of total hip and knee arthroplasty procedures in the United States in 2020 was 1.5 million, with an expected increase to more than 4 million by 2040.42

The prevalence of periprosthetic joint infection two years after total hip or knee arthroplasty is 1.63% and 1.55%, respectively, with an anticipated prevalence of more than 2% at 10 years for each of these procedures.43 A large European study found that 47% of periprosthetic joint infections occur within the first three months after surgery, 32% at three to 24 months, and 21% at greater than two years.44

Obesity has the strongest evidence for increased risk of periprosthetic joint infection after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Other risk factors with limited evidence include cardiac disease, immunocompromise, peripheral vascular disease, inflammatory arthritis, prior joint infection, renal or liver disease, mental health disorder (including depression), alcohol use, anemia, tobacco use, malnutrition, and diabetes.43

A validated clinical scoring system for the diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection was developed in 2018 (Table 6).45 If one of the major criteria is positive, no other evaluation is necessary for diagnosis. Otherwise, serum tests; synovial fluid tests; and, if the diagnosis is still unclear, intraoperative criteria are used.

| Criteria | Points |

|---|---|

| Major | |

| Two joint cultures positive for the same organism | — |

| Sinus tract communicating with joint | — |

| Scoring: Positive for infection if at least one major criterion is present; no further evaluation is needed. | |

| Minor | |

| Serum | |

| C-reactive protein > 1 mg per dL (10 mg per L) or d-dimer > 860 ng per mL | 2 |

| Estimated erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm per hour | 1 |

| Synovial fluid | |

| White blood cell count > 3,000 per μL (3 × 109 per L) or leukocyte esterase (++) | 3 |

| Alpha-defensin (signal-to-cutoff ratio > 1) | 3 |

| Polymorphonuclear leukocytes > 80% | 2 |

| C-reactive protein > 0.69 mg per dL (6.9 mg per L) | 1 |

| Scoring: ≥ 6 points = infection; 2 to 5 points = inconclusive; 0 to 1 = no infection. | |

| Optional intraoperative criteria if diagnosis is still unclear (2 to 5 points using minor criteria) | |

| Positive histology | 3 |

| Purulence | 3 |

| Single culture positive | 2 |

| Scoring (pre- and intraoperative criteria): ≥ 6 points = infection; 4 to 5 points = inconclusive; ≤ 3 = no infection. | |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Horowitz, et al.1

Data Sources: A PubMed search was initially completed using the key terms septic arthritis, Lyme arthritis, gonococcal arthritis, fungal arthritis, periprosthetic joint infection, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. An evidence summary from Essential Evidence Plus was also completed. Additional PubMed searches used the following key terms: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, lactate, radiologic evaluation, antimicrobial therapy, and prosthetic joint prophylaxis. Search dates: October and November 2020, March 2021, and September 2021.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Department or the U.S. Army at large.