A 12-month respite gave this family physician a new perspective on his personal and professional lives — and on himself.

Fam Pract Manag. 1998;5(4):37-44

Like most of us who choose a family medicine career, I have the propensity to say yes when asked to take on a new task. As a result, in 1995, I found myself enmeshed in a complex web of administrative responsibilities that had piled up to the point that my colleagues had begun calling me associate medical director. Clinical practice was much more difficult, too, with an increasing volume of patients needing care, fewer support staff and various entities looking over my shoulder to measure the quality of care and service I was providing. I devoted six days of the week to a combination of clinical and organizational work. I spent the seventh day recovering. About a third of the jobs on my to-do list never got done. Not at work, not at home. Deciding what not to get done and whom to disappoint this week became as important as doing what was most essential.

Then, on a busy day in 1995, a role model of mine stopped by my office. Mike had been a year ahead of me in our residency program in the early '70s. For more than a decade he had been director of the residency program, and he had also recently become chief of the family practice department. All of this in addition to maintaining a practice of his own. He strode into my office with his usual grace and confidence.

When I asked him how he managed to juggle so many responsibilities and maintain his sanity, he told me that the sabbatical he had taken just two years before helped him to get a better perspective on his work challenges: “It just changed my priorities,” I remember him saying. “I realized that my career is not my life, only part of it. Things that seemed so critical don't appear quite so serious now.”

The idea of a sabbatical was not new to me. Our employer, Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, gives its 650 or so physicians the option, every 10 years, of taking a year-long sabbatical. Experience has shown that people return from sabbatical renewed and refreshed, often bringing new skills to their patients or their practice. The organization doesn't restrict how physicians spend their sabbatical time. However, most physicians use the sabbatical to combine personal renewal with medical learning.

During the sabbatical year, physicians are paid 30 percent of their salary. Most supplement their sabbatical pay with savings to cover the costs of travel and other expenses. The 30-percent pay rate helps keep the program cost-neutral, because it is roughly the difference between the compensation of a 10-year physician and the cost of hiring a physician to fill in during the sabbatical. I had missed my first opportunity for sabbatical after my 10th year with the group. Leading the family practice department, starting a new department of prevention and other challenges had seemed more important than taking a long vacation. Mike's comments got me to thinking again about spending a year away from the pressure cooker, and I realized that, after 20 years, I was ready.

I had only about six months to figure out how to finance my year away and to make arrangements for my clinical and administrative work to be covered. My family was supportive of my desire to take a sabbatical and willing to make the sacrifices that my reduced income would necessitate. Three years of preparation would have been ideal, but six months turned out to be enough. I was careful to select a replacement whose practice style was similar to mine, to make the transition easier for patients. I sent a letter to my patients, explaining my upcoming sabbatical and introducing them to the physician who would be taking my place. Some patients expressed disappointment, but most were understanding and appreciated that I would be returning from the sabbatical refreshed and with new skills. I handed off my administrative responsibilities to other people, most of them family physicians looking for new, creative opportunities. I let go without reluctance, aware that the work would benefit from the vitality of fresh leadership. By December of 1995 I was off.

Planning the year for fullest benefit

The holiday rush was nothing in comparison with the rush I experienced during my first month of sabbatical. My excesses at work had left the other parts of my life unattended to for so long that they all seemed to me to demand attention at once. My days were filled with making gifts, sending cards, visiting friends, cooking for the family, visiting parents and in-laws, exercising, working on household chores long left undone, fixing up our beach house and property, taking classes, reading about a dozen books I'd been meaning to read and on and on.

By the end of the month, I was in a state of exhaustion and had learned the first lesson of my sabbatical: how much I had missed the other parts of my life. I concluded that if I didn't make a plan for how I would spend the next 11 months, I would risk replicating the too-busy approach I had taken to my career. I realized that I would have to pick and choose from a variety of activities because I didn't have time, even in a whole year, to do all the things that I had missed doing. I also realized that balancing the different parts of my life was a key to an enjoyable and successful sabbatical year — and to the years that would follow.

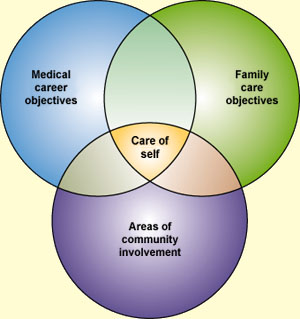

I took a different approach to my 1996 New Year's resolutions than I had in years past. I identified three parts of my life that I needed to feed in the months ahead. I wanted to find a way to balance those three parts, so I drew a Venn diagram consisting of three intersecting circles. One circle was my medical career. I wanted to find new ways of acquiring knowledge and skills that I could bring to my patients. Another circle was my family. Improving the connections with my children (then 16, 25 and 26) and my wife was critical to my future happiness and, I hoped, to theirs. The increasing complexity of my career had interrupted these connections for too long. My third circle was community involvement, getting more involved in church, activities with old friends, volunteering and finding new ways of being a community servant.

Pleased with my work, I shared the diagram with my wife, Mary. She had taken a sabbatical from her career as a family nurse practitioner about two years before, and her common sense was usually greater than mine.

After looking at the diagram for a moment, she said, “This is good, but isn't something missing? When are you going to do some things just for your own well-being?”

She was right, as usual. In a year intended for personal renewal, I had been blind to the need to take care of myself. I looked again at my diagram and noted the central field of the three intersecting circles. There I wrote, “me.” It was clear that my success would depend on my taking better care of myself.

Structuring the sabbatical

The author drew a Venn diagram like this one to help him plan his sabbatical year. He began by identifying three areas he wanted to focus on — career, family and community. Only after his wife commented on the omission did he appreciate that care of self was the vital center of the diagram, critical to meeting his goals in the other three areas. He went on to list specific activities in each of the circles. The design of the diagram helped him to keep his choices balanced.

Choosing the activities that matter most

The year went by quickly. I was able to relax, and I adapted to a slower pace. I considered doing a lot of different things, but I consciously limited my choices to achieve a reasonable balance. I attended to my Venn diagram to be sure my choices matched my goals.

For personal renewal, I turned to daily meditation, which I had learned before residency and used to help manage stress. I took long walks daily with my wife. It was good exercise and, more important, a captive time for us to chat. I took classes in voluntary simplicity with Mary, and together we divested ourselves of many material possessions that had trapped us, including the beach property that had become more an obligation than a joy. We began to attend church regularly; we took a class there on developing a personal theology, and used it to explore some of the basic questions of life that most of us don't take time to consider. I also spent lots of time outside. My family started calling me Dr. Dirt, because I loved digging in the vegetable garden. My bicycle became my main mode of transportation. I began to notice the seasons and changes in the weather. Stress symptoms decreased, weight dropped off without any real effort, and my well-being improved immensely.

My career enhancement activities ended up being fun and interesting. Here in the Northwest, many of our patients are looking for alternative therapy approaches, and they expect their family physicians to be conversant in complementary medicine strategies such as acupuncture, naturopathy and massage therapy. In addition to doing some reading on these subjects, I wanted to get some practical experience. I decided to enroll in one of the best massage therapy schools in the region, and by year end, I had become a licensed massage therapist. I really enjoyed the work, and I got rave reviews from my clients. During my time at the massage school, I also began to appreciate an approach to myofascial anatomy and kinesiology that blended art and science. I devoted 20 hours a week for nine months to the course of study. I made many great friends, and I developed a workbook for the school to help students apply what they learned.

My commitment to family seemed to develop almost without effort. Reconnecting with our two oldest children for Sunday dinner and other activities happened much more often, and I had the energy to devote to games, conversation and other family arts. We took weekend trips to the mountains and the ocean. My 16-year-old and I traveled to Indonesia for six weeks to visit long-time family friends. With Mary, every day became a new chance to develop our vision of where we are headed in this world, what contributions we want to make individually and together, and how to add quality to our lives and the lives of others.

My community involvement grew through the year. Providing support for the massage school was great fun, especially developing strategies to help my classmates learn the basics of anatomy, physiology and kinesiology. At church I began teaching the classes that I had taken, and every several weeks I would meet a new group of eight or 10 people wanting to explore the personal choices in their lives. The church community has become a platform for my concerns about social action, environmental preservation and spiritual growth.

Returning to work after a year

I once told myself I would never take a sabbatical because it would be too hard to go back to the demands of work. It turned out not to be so.

I returned to my clinical work with gusto. What a great opportunity it is for family physicians to participate in the health and well-being of the people who come to see us! In burnout, that opportunity is harder to see. Some of my patients chose to continue seeing other physicians, in part because the Group Health clinic where I began working after my sabbatical was different from the one where I worked before my sabbatical. I knew of the change before I left for my sabbatical, so I was prepared for the adjustment I had to make. In addition to maintaining a family practice, I was asked to focus on the population of patients with chronic pain due to nonmalignant conditions, approximately 5 percent of the roughly 400,000 patients that Group Health cares for. This has proven to be both a clinical and administrative challenge, involving population-based care strategies, physician education, patient education and direct care of some very needy folks. Finally, I have been asked to help with the organizational decision making on the development of an integrated computer system. I still say yes to new responsibilities far too easily.

One year has passed since I returned to work, and the life balance I've achieved and choices that go along with it still make sense. I miss the daily walks, but I am still using my bicycle for transportation. I miss contact with my classmates at massage school, but I am still teaching the class in personal theology development. Meditation and exercise no longer fit into my daily routine, but I find time for them at least four days a week.

I hear from others that a physician should keep his or her nose to the grindstone, but my sabbatical year convinced me once and for all of what I had for some time suspected was true: that as a physician, I have to take care of myself if I'm going to do any good for anyone else. My sabbatical year instilled in me a new approach to life, a different pace that continues to affect the choices I make as I go about my days as a family physician. It also was something of a prelude to the life episodes that will follow the end of my intense medical career.

I am not ready to retire yet; I enjoy the medical work too much. My sabbatical reminded me how much I enjoy the other parts of my life as well.

Making the time

The author's practice setting and the provisions that his employer makes for physicians to take sabbaticals enabled the author to make real what for some is just a passing thought. But physicians in private practice and in smaller group settings who've taken sabbaticals say where there's a will, there's a way.

Career transitions sometimes provide an avenue to sabbaticals. Carolyn Thiedke, MD, a family physician in the Charleston, S.C., area and a member of the Family Practice Management Board of Editors, negotiated sabbatical time in the process of negotiating the sale of her practice to a local hospital. Other physicians have taken sabbaticals as their groups have expanded, taking time off as a new physician joins the practice. A practice of six physicians in Washington state has made year-long sabbaticals business as usual; they cover for one another so that each can take a sabbatical every six years.

Transitions in personal lives, such as the months following the pay-off of a mortgage, can give some physicians the financial wherewithal to fund a sabbatical. Davis says some of his colleagues at Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound have decided the benefit of a sabbatical was worth withdrawing retirement savings to help finance it. Others who've left the area for sabbaticals have rented out their homes during their time away.

Obviously, a sabbatical requires careful planning, and some physicians may determine that leaving practice for a year is impossible. But, as Davis points out, a break from the pressures of medical practice needn't be a year long to be effective. An extended vacation devoted to self-renewal can help you to do your job better and feel better about your life.