Patients do better and cost less when they have ready access to primary care, but could your practice be thinking about access all wrong?

Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25(5):27-33

Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

These rising costs have real consequences for patients. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that, because of cost, 67 percent of the uninsured and 21 percent of the insured had forgone needed medical care.3 To address costs, payers are increasingly adopting reimbursement models that reward or penalize physicians based on their ability to keep costs down.

Now here's the good news: When it comes to rising health care costs, we in primary care are not the main problem, but we are a key part of the solution. This article will explain how improving access to primary care can reduce costs and the steps practices should begin taking now.

KEY POINTS

As a primary care physician, do not underestimate the power that access to your care has on reducing costs and improving health.

Commit to approaching access systematically, and review utilization data to identify key opportunities for improvement.

Not every patient request or problem needs the same time, method, person, or expertise from your practice. Begin to build your menu of access options.

Consider the modes of incoming access requests, the types of issues presenting, the team members available to meet the requests, and your scheduling methodology.

THE POWER OF PRIMARY CARE ACCESS

Research has shown that one of the most effective ways to address the cost problem in health care is to improve patients' access to primary care. The classic approach is to increase the supply of primary care physicians in a population or increase the ratio of primary care to specialty care. A 2004 study found that “Increasing the number of general practitioners in a state by 1 per 10,000 population (while decreasing the number of specialists to hold constant the total number of physicians) is associated with a rise in that state's quality rank of more than 10 places as well as a reduction in overall spending of $684 per beneficiary.”4

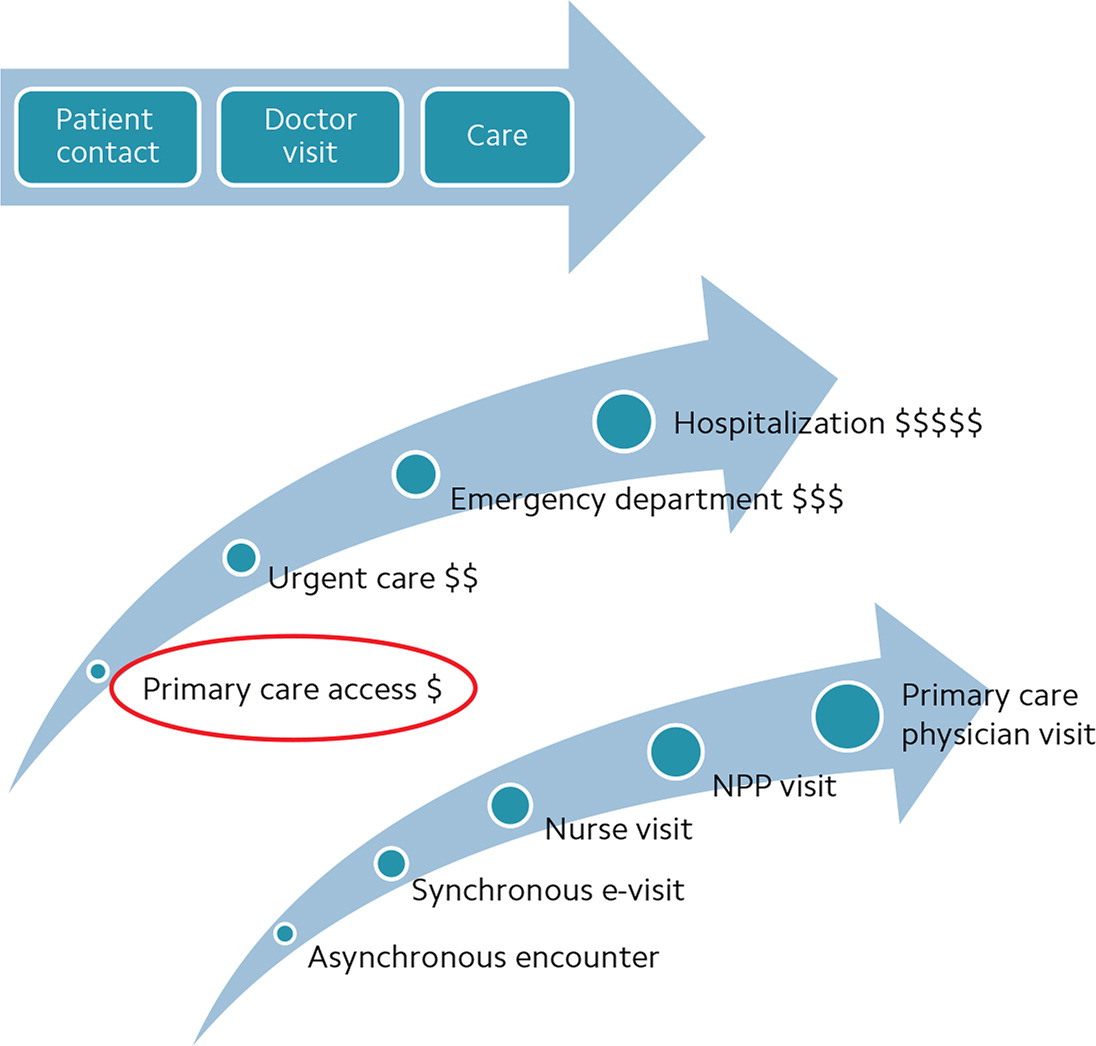

In other words, both quality and cost of care improve when patients have better access to a primary care physician. Having this trusting, continuous relationship increases the likelihood that patients will get the right care at the right time, potentially avoiding costly urgent and emergent care as well as hospitalizations.

Increased length of life, with fewer deaths due to heart and lung disease,

Better preventive care,

Reduced health disparities,

Less emergency department (ED) and hospital use,

Fewer tests,

Lower medication use,

Lower per capita costs of care.

As a primary care physician, do not underemphasize the importance of ready access to your care in improving outcomes and reducing cost. While we cannot individually increase the supply of primary care physicians in a community, we can powerfully affect our own practices and increase accessibility to our patients. Whether the number of primary care physicians increases or the supply stays stable while each primary care physician increases his or her access, either route gets to the same place — higher quality and lower cost care for our patients and community.

USING COST DRIVERS TO INFORM ACCESS IMPROVEMENT

To drive practices toward improved patient access, Medicare's Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+) program set the following requirements:

Maintain at least 95 percent empanelment, assigning each patient to a provider or care team,

Ensure patients have 24-hour-a-day/7-day-a-week access to their provider or a care team member who has real-time access to the electronic health record (EHR),

Organize care by teams responsible for a specific, identifiable panel of patients to optimize continuity,

Regularly offer at least one alternative to traditional office visits to increase access (e.g., e-visits, phone visits, group visits, or home visits) or expanded hours (e.g., early mornings, evenings, or weekends).

The CPC+ requirements offer a helpful framework for improving access, but keep in mind that optimal access means different things for different parts of your patient population. The kind of access a healthy patient requires isn't the same as what a patient with multiple chronic conditions or advanced illness requires.

Although high-risk patients generally make up a small percentage of a physician's panel (say, 5 percent of patients), they can account for a majority of medical costs. These high-risk, high-cost patients are the people you need to identify and engage creatively so that you can reduce their access barriers and their very high costs.

The most common cost drivers in primary care are the following:

Unnecessary readmissions,

Unnecessary primary admissions,

Unnecessary ED visits,

Excessive referrals to specialists (due to a physician's limited scope of practice),

Prescribing habits,

Lab/radiology ordering habits,

Ineffective chronic disease care,

Suboptimal preventive care.

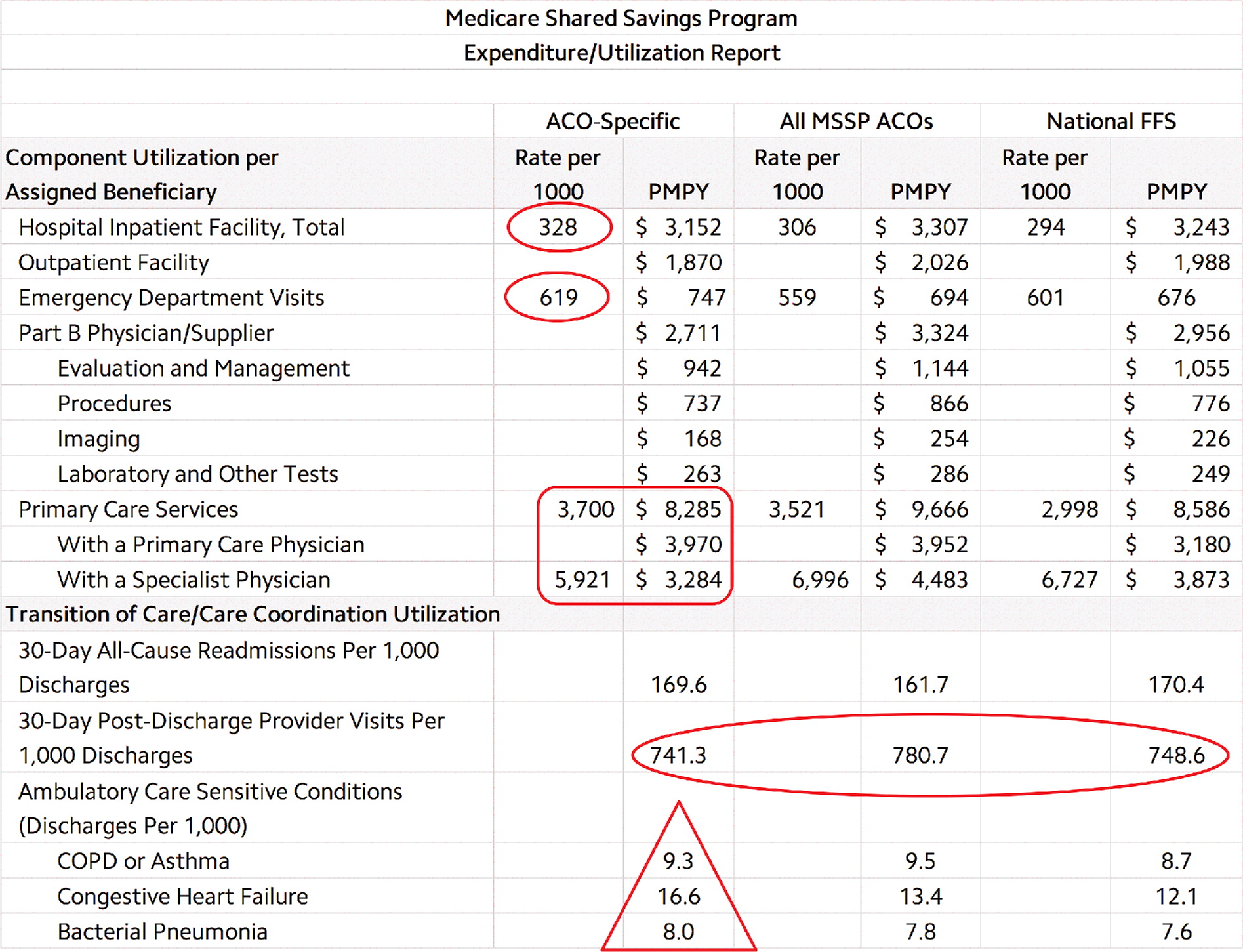

A cost or utilization report from a payer, or a program like CPC+ or a Medicare Shared Savings Program, offers powerful insight to how your practice meets access needs and, conversely, where to focus on improving access. For example, if your readmission costs are higher than desired, you may need to devise a more seamless transitional care management program and post-acute care follow up. If unnecessary ED presentations are the cost driver, you may be able to reduce them by emphasizing other alternatives such as same-day or weekend appointments paired with easier communication with the practice. If unnecessary primary admissions due to uncontrolled chronic disease are the cost driver, then you might try offering these patients more frequent access such as e-visits or phone visits with a nurse to improve their care management services. Utilization reports are a bright light shining into the practice and often readily identify access needs.

A “Sample cost report” is shown above. Conclusions that could be drawn from this report include the following:

Rates of inpatient hospitalization are higher than comparison practices, which suggests a possible need for improved acute illness access or improved chronic disease care,

Rates of ED use are higher than comparisons, which suggests a need for improved same-day care and reduced barriers to present for that care,

Higher rates of primary care services and lower rates of specialty care services than comparison practices suggest this practice is doing well with continuity care and follow-up access (as well as comprehensiveness and controlling unnecessary referrals),

Discharges for ambulatory sensitive conditions are in general higher than comparison practices, which suggests a need for improved chronic disease access and care.

By focusing on primary care access improvements, we have seen our quality and patient satisfaction scores improve while costs have gone down. Most notably, our all-cause hospital readmissions have decreased to the 75th percentile, total per-member-per-month costs of care for one of our private payers have decreased more than 12 percent, and our Medicare costs have decreased 5.4 percent.

THINKING BEYOND THE VISIT

The traditional view of access can be summarized by the phrase “The doctor will see you now.” Access was conceived of only as a face-to-face-visit, an idea built on the premise that the physician had to do everything personally and reinforced for 25 years by the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale and fee-for-service medicine.

To succeed in practice today, we need to think beyond this narrow view of access. We as physicians cannot possibly do all the work that is required for patient care. Several years ago, researchers calculated that it would take 21.7 hours a day, five days a week, to meet current clinical guideline recommendations for acute, chronic, and preventive care. They concluded, “There are not enough primary care physicians to meet the recommended care guidelines within the current model of a single physician providing all required preventive, chronic disease, and acute care to patients in his or her practice.”9

Providing optimal access is also more difficult today because of the following factors:

Slower documentation and slower patient cycle times because of EHRs,

Professional and lifestyle choices of a new generation of physicians,

Team-based care requiring interaction with the physician,

Increased demand due to an aging population and characteristics of baby boomers,

A shortage of family physicians due in part to an aging physician population that is slowing down as well as alternative practice options available to new residency graduates,

Value-based care's emphasis on quality and outcomes and related workflows, which requires extra data entry, checking the boxes, and “working the list,”

A trend of care being pushed to lower acuity settings, often to save money,

An increase in non-direct care “system” work such as preauthorizations, Family Medical Leave Act forms, wellness forms, and external screenings to review.

At the same time, patients now have many more choices for where, when, and how they receive care. Combine this with the trends toward patient autonomy, consumerism, transparent pricing and quality, and high-deductible health plans, and the new reality is this: “The patient will see you now.” If we cannot accommodate our patients when and how they want to be seen, someone else will.

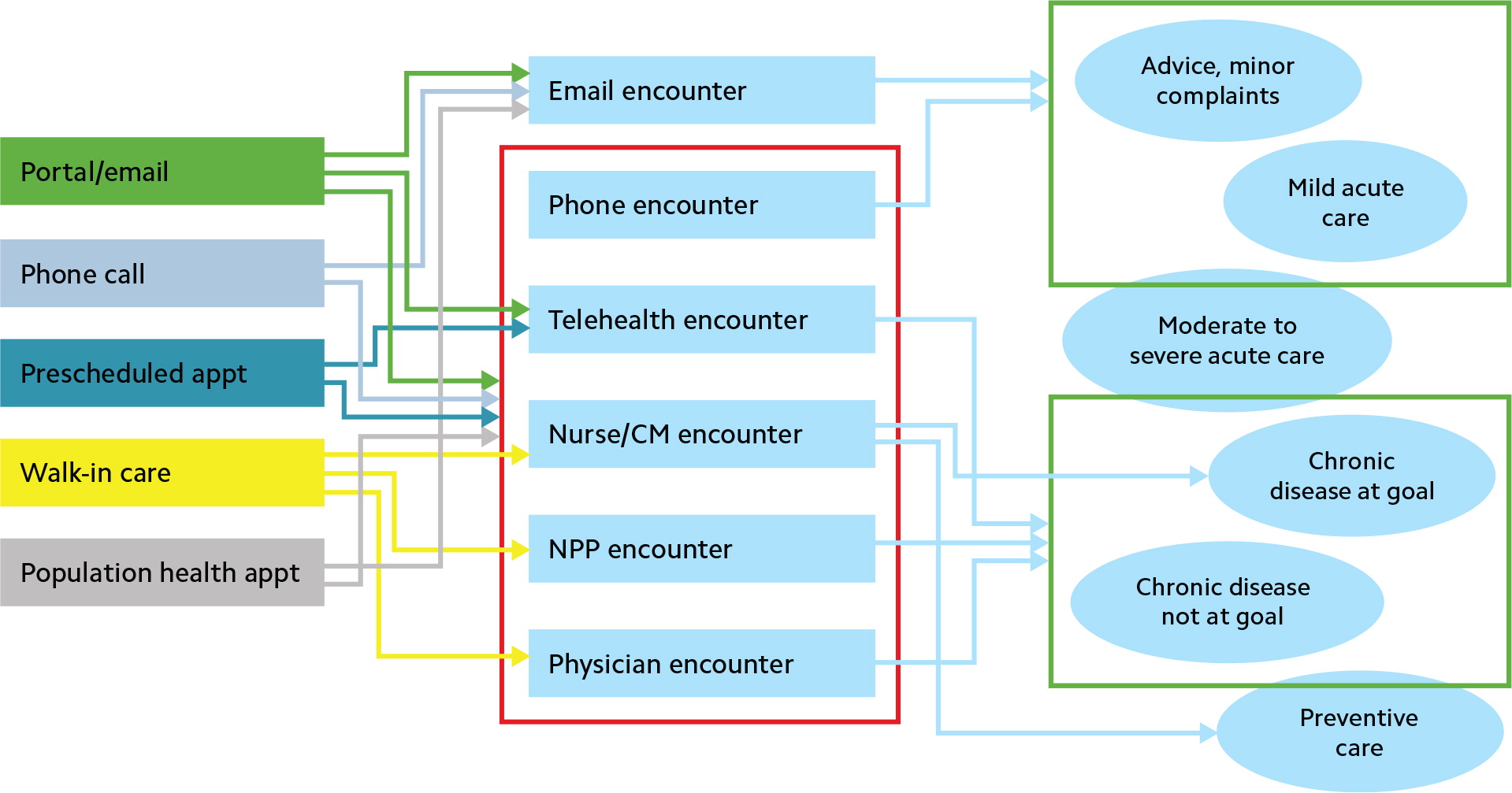

So, years ago, access was linear: an encounter equaled a visit with the physician, and that visit equaled a charge. Now, access has more of a fan-shaped distribution — many incoming access points involving different members of the care team (see “Access then and now”). And the implications for cost are that each of the possible access points has different, and steadily increasing, costs associated with it.

BUILDING YOUR MENU OF OPTIONS

This new way of thinking about access better reflects the reality that not every patient request or problem needs the same time, method, person, or expertise from your practice. Instead, patients need a variety of access options:

Office visits with the physician,

Office visits with a nonphysician provider,

Office visits with other advanced primary care team members (nurse, care manager, pharmacist, health coach, social worker, behavioral health specialist, etc.),

Phone encounters,

Online asynchronous encounters (email),

Online synchronous encounters (tele-health visits),

Gap management (team engagement with the patient present or not).

The challenge is to build a system in your practice that matches the type of patient request or problem with the type of encounter that can appropriately meet the need at the lowest cost. For example, if a patient calls or uses your portal to ask a simple health question, then an appropriate access strategy at the lowest cost is simply a return phone call or portal message. On the other hand, if a patient whose chronic disease is not at goal contacts your office, the most appropriate access is likely an office visit with the physician or a non-physician provider. (See “Matching patient requests with access solutions.”)

MATCHING PATIENT REQUESTS WITH ACCESS SOLUTIONS

| Patient communication channel and complaint | Encounter option |

|---|---|

| Phone, portal — health question | Phone, portal/email/text |

| Phone, portal — acute illness (mild) | Phone, portal/email/text care pathway or protocol; nurse or nonphysician provider (NPP) visit |

| Phone, portal — acute illness (sick) | NPP or physician visit |

| Preventive/wellness care gap | Phone, portal/email/text; nurse visit; NPP or physician visit |

| Incoming request or outgoing contact from the practice about chronic disease at goal | Nurse care pathway or protocol; NPP visit |

| Incoming request or outgoing contact from the practice about chronic disease not at goal | NPP or physician visit |

Here's what this might look like in practice (partial example):

A practice's appointment scheduling system is crucial in all of this, so you need to assess whether yours is working. The key is whether it enables you to provide timely care to your own patients.

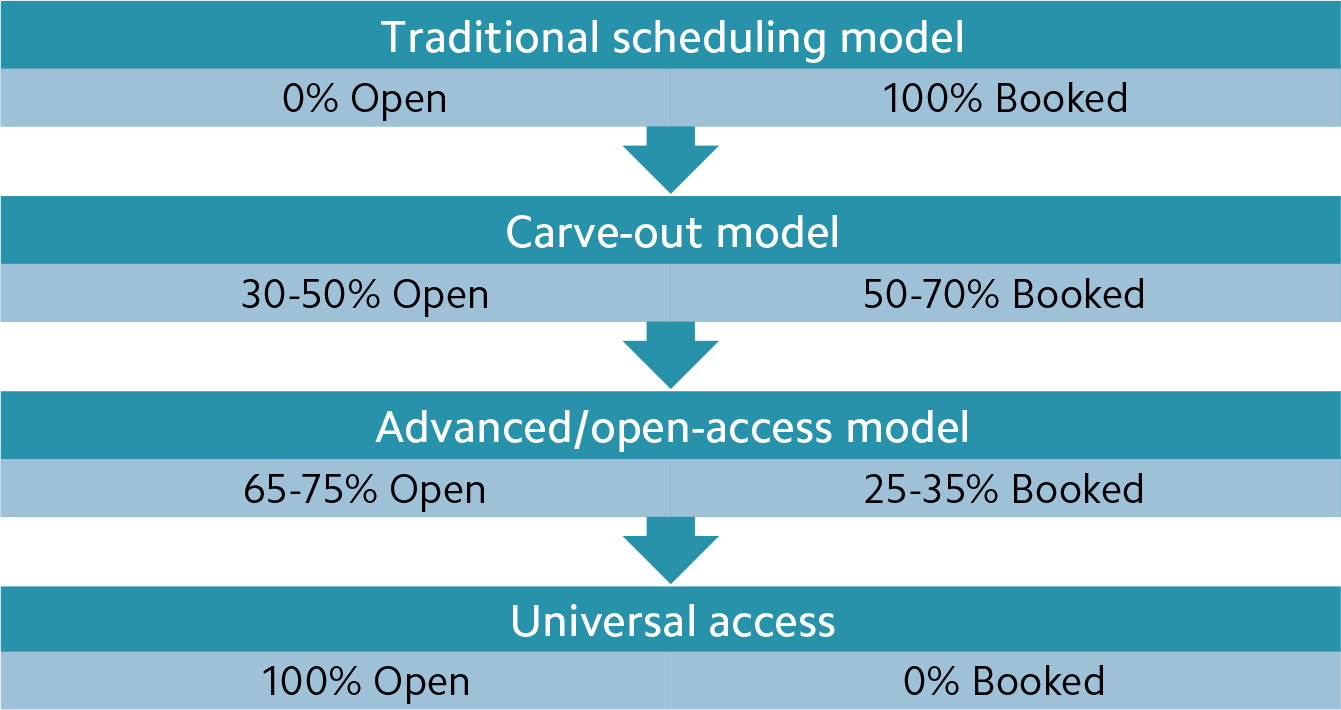

In general, reduced complexity makes for a better scheduling system. That means using fewer appointment types and a simple short/long duration for appointments so that any patient can have any appointment slot. Of all the various scheduling systems available to practices, the one that optimizes patient access best (without any other considerations) is universal access, because 100 percent of appointment slots are open at the start of each day, ready to be filled with same-day requests (see “Access under common scheduling systems”). However, for most practices, having a schedule that is 100-percent open isn't fully practical or desirable, in part because some patients do want to schedule their appointments in advance and there may occasionally be clinical reasons for doing so. Advanced/open-access scheduling allows for this while leaving most appointment slots open to meet the day's demand. (For advice on how to transition your scheduling system to the open-access model, see “Same-Day Appointments: Exploding the Access Paradigm,” FPM, September 2000.)

ACCESS MATTERS

Ultimately, when patients have better access to primary care — your care and that of your team — their health improves and costs go down. Thinking about access to your team's care comprehensively and systematically and planning one or two steps you will take to improve access in your practice will not only benefit your patients. It will also increase your value in an increasingly value-focused health care system.