Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(10):605-613

Related letter to the Editor: Weight-Based Levothyroxine Dosage Adjustment for Hypothyroidism

Related letter to the Editor: Family Physicians Should Treat Pregnant Patients With Hypothyroidism

Clinical hypothyroidism affects one in 300 people in the United States, with a higher prevalence among female and older patients. Symptoms range from minimal to life-threatening (myxedema coma); more common symptoms include cold intolerance, fatigue, weight gain, dry skin, constipation, and voice changes. The signs and symptoms that suggest thyroid dysfunction are nonspecific and nondiagnostic, especially early in disease presentation; therefore, a diagnosis is based on blood levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine. There is no evidence that population screening is beneficial. Symptom relief and normalized thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are achieved with levothyroxine replacement therapy, started at 1.5 to 1.8 mcg per kg per day. Adding triiodothyronine is not recommended, even in patients with persistent symptoms and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone. Patients older than 60 years or with known or suspected ischemic heart disease should start at a lower dosage of levothyroxine (12.5 to 50 mcg per day). Women with hypothyroidism who become pregnant should increase their weekly dosage by 30% up to nine doses per week (i.e., take one extra dose twice per week), followed by monthly evaluation and management. Patients with persistent symptoms after adequate levothyroxine dosing should be reassessed for other causes or the need for referral. Early recognition of myxedema coma and appropriate treatment is essential. Most patients with subclinical hypothyroidism do not benefit from treatment unless the thyroid-stimulating hormone level is greater than 10 mIU per L or the thyroid peroxidase antibody is elevated.

Hypothyroidism occurs when there is inadequate thyroid hormone production by the thyroid gland or insufficient stimulation by the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. Causes may include primary gland failure or can be iatrogenic, transient, or central (Table 1).1–4 Central causes, such as low levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4), are rare.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not screen asymptomatic pregnant patients for subclinical hypothyroidism. | Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine |

| Do not order multiple tests for the initial evaluation of a patient with suspected thyroid disease. Order thyroid-stimulating hormone level and, if abnormal, follow up with additional evaluation or treatment depending on the findings. | American Society for Clinical Pathology |

| Do not routinely order thyroid ultrasonography in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests if there is no palpable abnormality of the thyroid gland. | Endocrine Society/American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists |

| Do not obtain a total or free triiodothyronine level when assessing levothyroxine dose in patients with hypothyroidism. | Endocrine Society/American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists |

| Central (hypothalamic or pituitary) Inappropriately normal or low levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone despite low thyroid hormone Medications (amiodarone, immune checkpoint inhibitors, interleukin-2, interferon-alfa, lithium, tyrosine kinase inhibitors)* Pituitary tumor or disorder Iatrogenic Hyperthyroid treatment (radioactive iodine or antithyroid medications)* Radiation therapy to treat head and neck cancers* Thyroid surgery* Primary gland failure Autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto thyroiditis)† Congenital abnormalities Infiltrative diseases Severe iodine deficiency or relative excess‡ Transient Postpartum thyroiditis Pregnancy Silent thyroiditis Subacute thyroiditis Thyroiditis associated with thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor–blocking antibodies |

Clinical hypothyroidism occurs in 0.3% of the U.S. general population, with a higher prevalence in people older than 65 years.5–7 It is seven times more common in females than in males (40 out of 10,000 vs. six out of 10,000).8 Other risk factors include autoimmune disease (e.g., type 1 diabetes mellitus, celiac disease, autoimmune gastric atrophy, multiple autoimmune endocrinopathies), Down syndrome, and Turner syndrome.2 Cigarette smoking and moderate alcohol intake decrease the risk of thyroid cancer and hypothyroidism.2,9 Untreated hypothyroidism can contribute to numerous physiologic and metabolic derangements.

Signs and symptoms are nonspecific and can vary in individual presentations (Table 2 and Table 31,3,10). Diagnosis is based on blood levels of decreased FT4, with a corresponding elevated thyrotropin (i.e., TSH) level in primary causes (thyroid source); the TSH level may be normal to low in secondary (pituitary source) or tertiary (hypothalamic source) causes.5 Subclinical hypothyroidism describes the state of normal FT4 levels when the TSH level is elevated. This article focuses on primary hypothyroidism in adults.

| Bradycardia Coarse facies Cognitive impairment Delayed relaxation phase of deep tendon reflexes Diastolic hypertension Edema Goiter Hoarseness Hypothermia Laboratory abnormalities Anemia (normocytic) Elevated C-reactive protein Hyperprolactinemia Hyponatremia Increased creatine kinase Increased low-density lipoprotein Increased triglycerides Proteinuria Lateral eyebrow thinning Low-voltage electrocardiography Macroglossia Pericardial effusion Periorbital edema Pleural effusion |

Pathophysiology

A sensitive negative feedback loop regulates the thyroid hormone. The hypothalamus produces thyrotropin-releasing hormone that controls anterior pituitary gland secretion of TSH, regulating the secretion of thyroid hormone (triiodothyronine [T3] and thyroxine [T4]) by the thyroid gland.11,12 Thyroid hormone affects the metabolism and function of many cells and organs. This central role is reflected by the signs and symptoms of thyroid dysregulation. Thyroid hormone also regulates thyroid metabolism by providing negative feedback to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The hypothalamus adjusts the release of thyrotropin-releasing hormone based on circulating levels of thyroid hormone. Together, these hormones regulate the secretion of TSH from the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. This functioning feedback loop keeps the blood level of the thyroid hormone normal.

Screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force concludes that there is insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for thyroid dysfunction in nonpregnant, asymptomatic adults.13 Consider targeted screening at initial diagnosis or medication initiation in patients with Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, subtotal thyroidectomy, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (Addison disease), radioiodine treatment, radiation therapy of the neck, and use of medications such as amiodarone, lithium, interferons, and rifampin.2,3 Other medications that may prompt screening include tyrosine kinase inhibitors, phenobarbital, interleukin-2, and immune checkpoint inhibitors.3,14

Diagnosis

TSH elevation indicates hypothyroidism. Low-end normal TSH is 0.4 mIU per L.2,5–7 The upper-end normal range is from 4.0 to 4.5 mIU per L.2,5–7 FT4 level is used to distinguish clinical (low FT4) from subclinical (normal FT4) hypothyroidism. Routinely evaluating total T3, total T4, or FT3 levels is not indicated.2 Testing for the thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody does not help diagnose hypothyroidism; however, a positive test result suggests an autoimmune etiology.2 Thyroid ultrasonography is used to evaluate palpable thyroid nodules and is not part of routine evaluation.4

EVALUATING FOR SUSPECTED HYPOTHYROIDISM

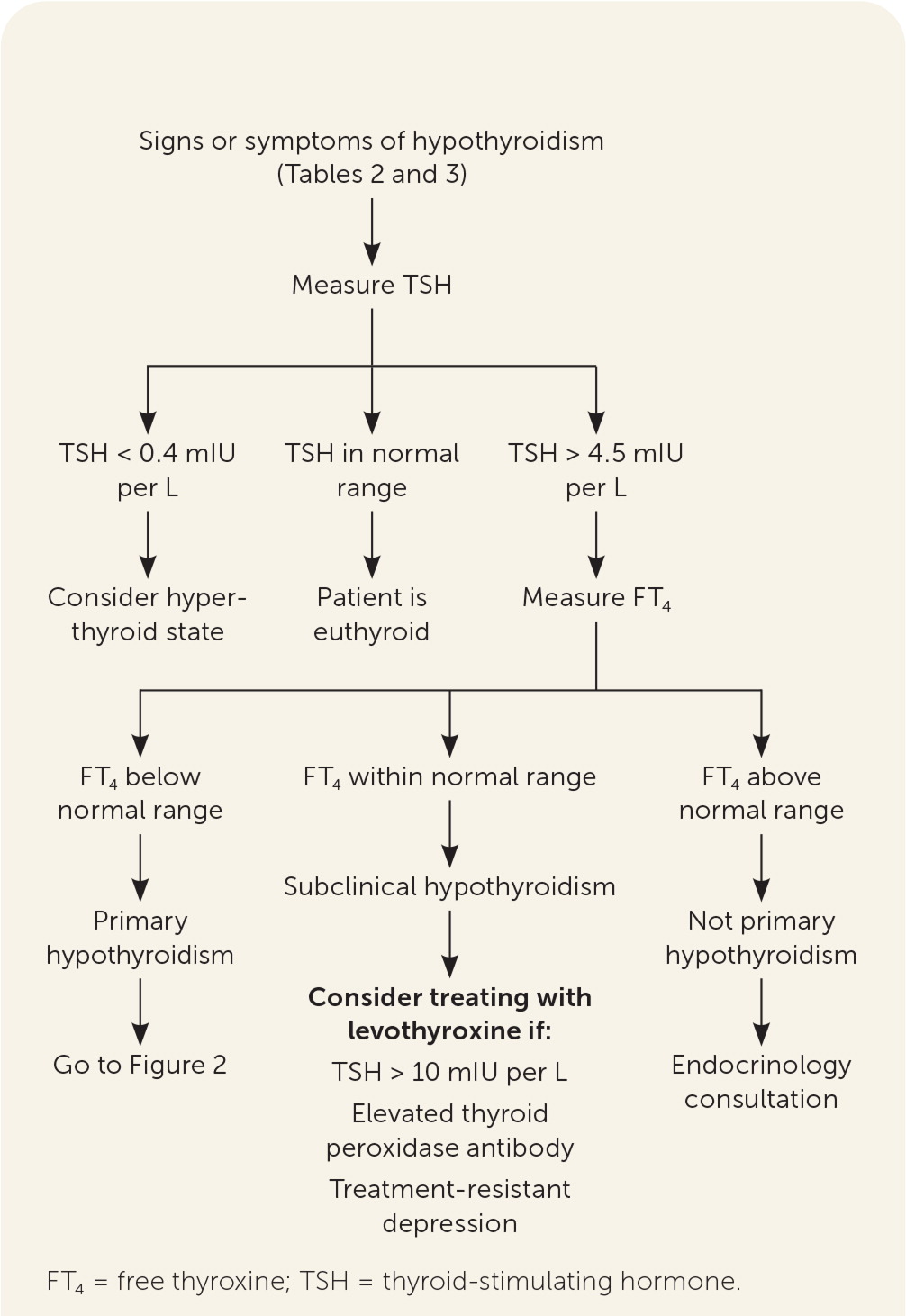

When signs and symptoms raise the index of suspicion, the clinician should obtain a serum TSH level (Figure 12,5–7,15–17). If the TSH level is within the normal reference range, other etiologies for the signs and symptoms that prompted testing should be sought (Table 41,2). If a pituitary cause is suspected, an FT4 level is obtained. If the FT4 level is normal, further thyroid or pituitary evaluation is unnecessary. If the FT4 level is low, the clinician should review medications the patient is taking, evaluate the pituitary gland, or consider euthyroid sick syndrome (i.e., a normal TSH level with abnormal thyroid hormone levels and function tests that can occur in patients with severe nonthyroid systemic disease despite actual normal thyroid function).

| Anemia (vitamin B12 or iron deficiency) Autoimmune (rare) Adrenal insufficiency Atrophic gastritis with pernicious anemia Diabetes mellitus type 1 Rheumatoid arthritis Chronic kidney disease Liver disease Menopause Mental health (i.e., depression, anxiety, or somatoform disorders) Obstructive sleep apnea Viral infections (e.g., mononucleosis, Lyme disease, HIV) |

If the TSH level is low (less than 0.4 mIU per L), hyperthyroidism is possible.18 If the TSH level is high (greater than 4.5 mIU per L), a serum FT4 level should be obtained. A low FT4 level indicates clinical hypothyroidism, specifically autoimmune hypothyroidism (i.e., Hashimoto thyroiditis) if the TPO antibody test result is elevated). Table 1 lists other causes.1–4 An elevated FT4 level may suggest a TSH-secreting tumor, and referral to endocrinology is warranted. An FT4 level within the reference range indicates subclinical hypothyroidism. Rare other causes include adrenal insufficiency, drugs, post-nonthyroidal illness, or thyroid hormone resistance syndrome.2 Thyroid hormone resistance syndrome, which occurs in one out of 40,000 live births, results from mutations of the thyroid hormone receptor that cause decreased tissue responsiveness to thyroid hormone, leading to an elevated FT4 level and a normal or elevated TSH level.19

Treatment

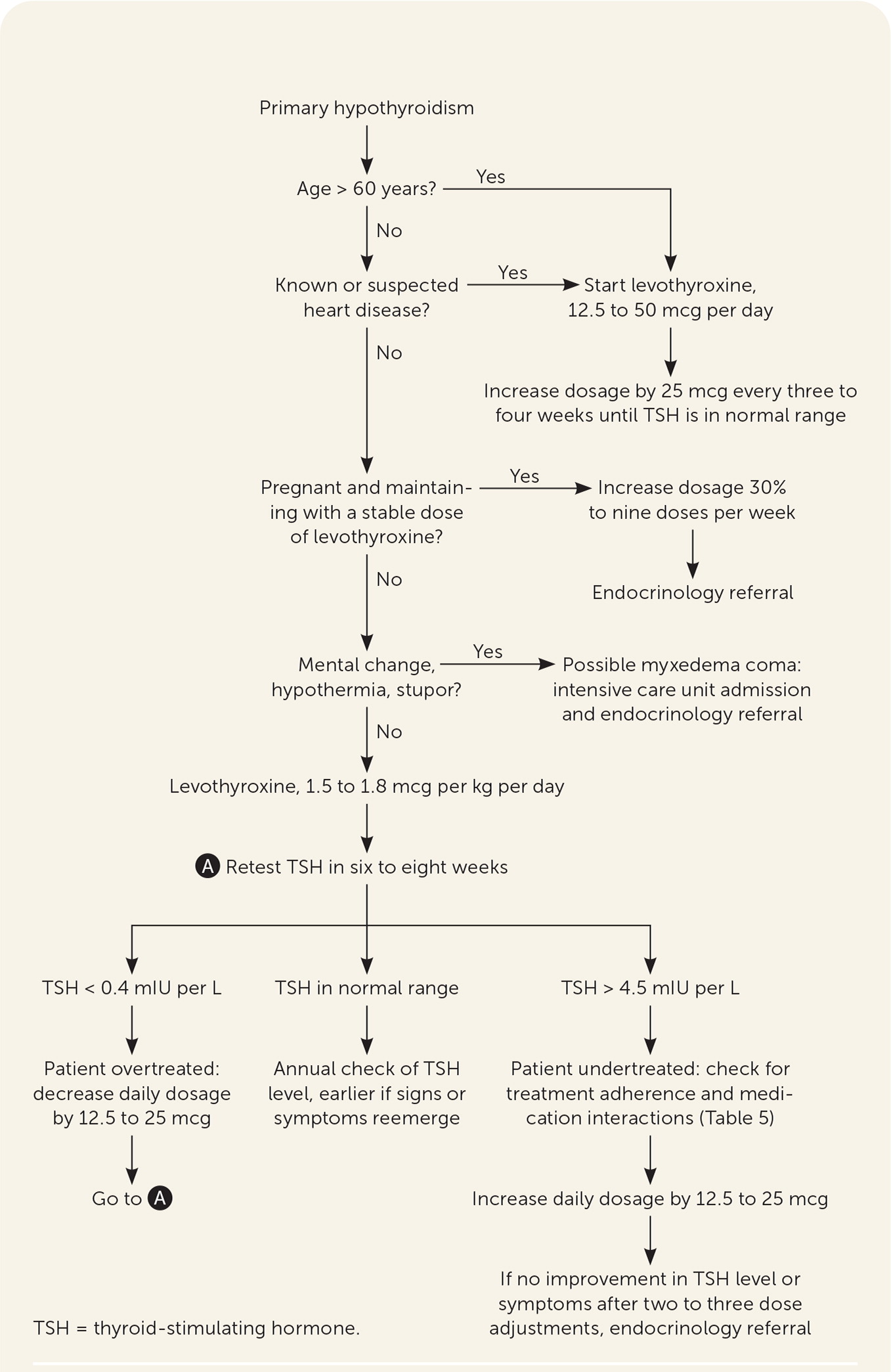

Clinical hypothyroidism should be treated with levothyroxine to normalize the TSH level and relieve signs and symptoms (Figure 22,3,5,7,10,20–25). Evidence does not support the use of T3 , alone or in combination with levothyroxine.5,26 Iodine supplementation, including kelp or other iodine-rich foods, should not be used in iodine-sufficient geographic locations.5

Levothyroxine should be taken once per day, 30 to 60 minutes before eating, and four hours before or after drugs that may impede absorption (Table 520). Table 6 addresses initial dosing of levothyroxine.2,3,5,20,21 In patients who are not pregnant, TSH should be monitored every six to eight weeks until within normal range, then every six to 12 months, barring a change in clinical status.20 Some drugs and conditions (Table 72,20) can affect levothyroxine metabolism and effects, and drug-drug and drug-food interactions (Table 820) can affect levels of levothyroxine or the concomitant drug. A lower symptom threshold should be used to monitor the TSH level in patients at risk of these interactions and when medications or dosing changes are initiated.20

| Bile acid sequestrants (e.g., colesevelam [Welchol], cholestyramine [Questran], colestipol) |

| Calcium carbonate |

| Ferrous sulfate |

| Intragastric pH elevation via hypochlorhydria |

| Antacids (e.g., aluminum, magnesium) |

| Proton pump inhibitors |

| Simethicone |

| Sucralfate (Carafate) |

| Ion exchange resins (e.g., sodium polystyrene sulfonate, sevelamer [Renvela]) |

| Orlistat (Xenical) |

| Patient group | Dosing |

|---|---|

| Age younger than 60 years | Start with 1.5 to 1.8 mcg per kg per day |

| Age 60 years or older; known or suspected heart disease | Start with 12.5 to 50 mcg per day |

| Pregnant on previously stable dose | Increase to nine doses per week; endocrine referral |

| Change in adherence (e.g., missing doses) |

| Change in timing of medication relative to eating |

| Malabsorption |

| Autoimmune atrophic gastritis |

| Celiac disease |

| Diabetic gastropathy |

| Helicobacter pylori gastritis |

| Medication, new initiation |

| Androgens |

| Estrogens |

| Heroin/methadone |

| Medications that decrease absorption of levothyroxine (Table 5) |

| Medications that may alter hepatic metabolism of levothyroxine (phenobarbital, rifampin) |

| Medications that may decrease levothyroxine conversion to triiodothyronine (amiodarone, high-dose beta-adrenergic agonists, glucocorticoids) |

| Medications that may reduce serum protein binding of levothyroxine (carbamazepine [Tegretol] or phenytoin [Dilantin]) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants |

| Tamoxifen |

| Pregnancy |

| Diabetes mellitus medications | May increase dosing of diabetes medications needed to achieve glycemic control |

| Digitalis | May decrease serum digitalis levels |

| Foods | Patients who regularly consume walnuts, dietary fiber, soybean flour, cottonseed meal, or grapefruit juice may need higher doses of levothyroxine |

| Ketamine | Concurrent use may result in significant hypertension and tachycardia |

| Oral anticoagulants | May increase effects |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | May increase therapeutic and toxic effects |

| Sympathomimetics | Concurrent use may increase risk of a cardiac event in patients with coronary artery disease |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | May increase therapeutic and toxic effects |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | Concurrent use may result in hypothyroidism |

LABORATORY ASSESSMENT AFTER INITIAL DOSING

Once the TSH level is normalized, it should be rechecked in one year or earlier if symptoms change. Extending the frequency beyond one year is reasonable in patients with a normal TSH level, stable symptoms, and daily dosing of levothyroxine of less than 75 mcg per day.27

If the TSH level is abnormal, the clinician should assess patient adherence, evaluate drug-drug interactions, and adjust the levothyroxine dosage every six to eight weeks until the TSH level normalizes (Figure 22,3,5,7,10,20–25). When TSH is low (over-replacement), the daily dosage should be decreased by 12.5 to 25 mcg. When TSH is high (under-replacement), the daily dosage is increased by 12.5 to 25 mcg per day. If the TSH level or symptoms are not improving after two to three cycles of adjustments, referral to endocrinology may be considered after reassessment of the differential diagnosis, patient adherence, and drug-drug or drug-food interactions.

Special Populations

PATIENTS OLDER THAN 60 YEARS AND PATIENTS WITH ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE

In older adults, hypothyroidism may have a subtle or more nonspecific presentation. Few older patients with confirmed hypothyroidism have overt symptoms to suggest disease.28 Serum TSH levels can increase with age, and mild elevations do not necessarily reflect subclinical hypothyroidism.29 A randomized placebo-controlled trial of 737 patients older than 65 years with subclinical hypothyroidism demonstrated no significant improvement in quality of life with levothyroxine treatment.7 A separate study found no association between subclinical hypothyroidism and ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or cardiovascular death.30 Thyroid hormone has known inotropic effects on cardiac tissue and can increase myocardial oxygen demand. For older patients or those with coronary artery disease, levothyroxine therapy should be started at 25 to 50 mcg per day, with titration of 25 mcg every three to four weeks until a target dosage is achieved to decrease the potential for adverse effects from thyroid excess (e.g., atrial fibrillation, dysrhythmia, angina, osteoporosis). Starting as low as 12.5 mcg per day in patients at higher risk (e.g., advanced age, heart disease) should be considered.2,3,5,21

PREGNANT PATIENTS

Pregnancy is associated with increased levothyroxine requirements as early as the fourth week of gestation.22 TSH levels decrease in early pregnancy because of weak stimulation of TSH receptors by human chorionic gonadotropin in the first trimester, then return to normal throughout pregnancy. Once pregnancy is confirmed, patients with existing hypothyroidism should start taking an extra dose of levothyroxine two days per week for a total of nine doses per week.22 This significantly decreases the risk of maternal hypothyroidism during the first trimester.22 Further treatment is guided by measuring TSH levels at the first prenatal visit, then every four weeks with titration of levothyroxine according to the pregnancy-specific TSH reference range.22,23 The lower and upper limits of normal TSH drift downward during pregnancy, which, with geographic and ethnic variation,21 supports consideration to include endocrinology referral in managing pregnant patients with hypothyroidism.

Clinical hypothyroidism complicates two to 10 per 1,000 pregnancies; Hashimoto thyroiditis is the most common cause. Untreated hypothyroidism can result in spontaneous abortion, preeclampsia, preterm birth, abruptio placentae, and fetal death.26 TSH should be evaluated in pregnant patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism, a goiter, a history of thyroid disease, TPO antibody positivity, or autoimmune disease.26 Patients with a TSH level greater than 2.5 mIU per L who are TPO antibody–positive have a higher risk of pregnancy-related complications, including preterm birth and pregnancy loss.23 Universal screening for hypothyroidism in pregnancy is not recommended because the identification and treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy do not improve outcomes.23,26 A randomized trial of 21,846 women found no difference in neurocognitive development of children from women screened and treated for subclinical hypothyroidism.31

PATIENTS WITH PERSISTENT SYMPTOMS

Patients on high dosages of levothyroxine (greater than 200 mcg per day) with persistently elevated TSH levels may be nonadherent or have absorption issues attributed to meal timing or other medications1,5,20 (Table 5 and Table 820). Some patients may experience persistent symptoms despite adequate dosing of levothyroxine to a normal TSH level; therefore, other etiologies should be considered and evaluated accordingly (Table 41,2).

Some patients with a normal TSH level and symptom resolution may become symptomatic again with or without a change in TSH. When symptoms reappear without a change in TSH level, the physician should consider nonthyroid etiologies. When there is an accompanying change in the TSH level, especially in a patient who has stayed on a stable dosage for some time, other reasons should be explored before adjusting the levothyroxine dosage.

Adding T3 to levothyroxine does not additionally alleviate symptoms of hypothyroidism. A meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials (n = 1,216) found no difference in symptoms or quality of life in patients treated with levothyroxine monotherapy vs. levothyroxine plus combination therapy.32 The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists does not recommend desiccated thyroid hormone and finds insufficient evidence to recommend combination levothyroxine/T3 therapy over levothyroxine monotherapy.5 The American Thyroid Association does not recommend genetic testing for polymorphisms to guide treatment; however, a small subset of patients with specific type 2 deiodinase polymorphism may benefit from combination therapy.21

MYXEDEMA COMA

Rarely, severe hypothyroidism can cause myxedema coma, a medical emergency most commonly found in older patients with primary hypothyroidism, with a 25% to 60% mortality rate.24 Early recognition with appropriate treatment is essential. Clinical features include hypothermia and mental status changes (e.g., lethargy, confusion, psychosis), hypotension, bradycardia, hypoventilation, and diffuse nonpitting edema. Abnormal laboratory findings include hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, high TSH, very low FT4, and low cortisol if associated adrenal insufficiency exists. When myxedema coma is suspected, treatment can be initiated while waiting for confirmation of laboratory test results. Myxedema coma is one of the reasons for referral to endocrinology (Table 91,3–5).

| Age 18 years or younger |

| Elusive euthyroid state |

| Myxedema coma, suspected |

| Pregnancy |

| Simultaneous presence of another endocrinopathy |

| Structural change in thyroid gland (e.g., goiter, nodule) |

| Symptoms do not improve or worsen after treatment with levothyroxine |

| Unstable ischemic heart disease |

Few clinical trials exist to guide treatment, although experts recommend levothyroxine, T3, or both.25 Levothyroxine should be given as a slow intravenous bolus of 200 to 400 mcg initially, followed by 50 to 100 mcg (about 1.6 mcg per kg) orally per day. Reduce dosing by 75% if it is being administered intravenously. For combination treatment, T3 is given at the same time as levothyroxine and dosed at 5 to 20 mcg, then 2.5 to 10 mcg every eight hours until clinical improvement. Lower dosages are appropriate in older adults and patients with a history of cardiovascular disease. Stress-dose glucocorticoids (e.g., 100 mg of hydrocortisone intravenously every eight hours) should be administered until adrenal insufficiency is ruled out. Serum FT4 and T3 should be monitored every one to two days, with samples drawn at least one hour after dosing T3. The TSH level should drop by 50% per week on adequate treatment. After clinical improvement, the patient may transition to oral levothyroxine monotherapy.21,25

SUBCLINICAL HYPOTHYROIDISM

Subclinical hypothyroidism is a biochemical finding of an elevated TSH level with a normal FT4 level. This finding should initiate a TPO antibody test and an additional TSH test in six to 12 months. Subclinical hypothyroidism is present in 3.7% of the U.S. population.6 Signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism may or may not be present. After 12 or more months, TSH often spontaneously normalizes.7 More than 50% of patients older than 55 years with TSH levels of 5.0 to 9.9 mIU per L will normalize, whereas only 13% and 5% of patients normalize if the TSH level is greater than 10 mIU per L or greater than 15 mIU per L, respectively.33 Patients with elevated TPO antibody titers are at an increased risk of progression to clinical hypothyroidism.34 Annual progression from subclinical to clinical hypothyroidism is 5.6% for a TSH level greater than 6 mIU per L.34

Subclinical hypothyroidism is common in patients 65 years and older. Despite observed associations with depression, cognitive impairment, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease, there is no evidence that treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism improves outcomes. A study of 737 patients who were 65 years and older with subclinical hypothyroidism found no improvement in quality of life or clinical outcomes with levothyroxine titrated to achieve a normal TSH level compared with patients who received placebo with sham titration.7 In patients 65 years and older with subclinical hypothyroidism and TSH levels less than 10 mIU per L, treatment with levothyroxine can increase mortality.35 The benefit of treating subclinical hypothyroidism in many populations is uncertain. One randomized controlled trial found that treating middle-aged adults (mean age of 57 years) with levothyroxine compared with a control medication decreased tiredness.36 However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 randomized controlled trials of 2,192 adults found that the treatment was not associated with improved quality of life or thyroid-related symptoms.37 A Cochrane systematic review was inconclusive about the value of treating subclinical hypothyroidism in women who are infertile.38 Although subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy is associated with adverse outcomes such as miscarriage, preterm delivery, low birth weight, and lower IQ in offspring, clinical trial results have been mixed. One trial found a decreased risk of preterm birth in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism and TPO antibodies.39 Two trials demonstrated that levothyroxine did not improve adverse pregnancy outcomes or the IQ of offspring of pregnant patients with subclinical hypothyroidism.31,40 A systematic review and meta-analysis found an excess risk of depression in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism but no improvement with the use of levothyroxine.41 Thyroid hormone therapy may benefit patients with treatment-resistant depression and TSH levels greater than 2.5 mIU per L.15

Most adults older than 30 years with elevated TSH but normal FT4 levels do not benefit from thyroid hormone therapy, and 60% normalize within five years.37,42 Patients who have a TSH level greater than 10 mIU per L are at higher risk of fracture, ischemic heart disease, and heart failure compared with patients who have a TSH level of 2.0 to 2.5 mIU per L.16 In nonpregnant patients with subclinical hypothyroidism, levothyroxine therapy should be considered when the TSH level is greater than 10 mIU per L or the TPO antibody level is elevated.16,17,34 The benefits of treating women with subclinical hypothyroidism who are pregnant or attempting to conceive are unclear.17

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Hueston,43 and Gaitonde, et al.1

Data Sources: A search of Dynamed, Essential Evidence Plus, and PubMed was conducted using the key terms hypothyroidism, pregnancy, diagnosis, treatment, and subclinical hypothyroidism. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and guidelines. Search dates: October and November 2019.