Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(4):667-674

Patient information: See related handout on exercises to strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff, written by the authors of this article.

Rotator cuff impingement syndrome and associated rotator cuff tears are commonly encountered shoulder problems. Symptoms include pain, weakness and loss of motion. Causes of impingement include acromioclavicular joint arthritis, calcified coracoacromial ligament, structural abnormalities of the acromion and weakness of the rotator cuff muscles. Conservative treatment (rest, ice packs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy) is usually sufficient. Some patients benefit from steroid injection, and a few require surgery.

Family physicians who understand rotator cuff pathology and can perform a concise examination of the shoulder can readily diagnose and treat impingement and tears of the rotator cuff. This article reviews the rotator cuff syndrome and lays a foundation for its appropriate recognition and treatment.

Anatomy

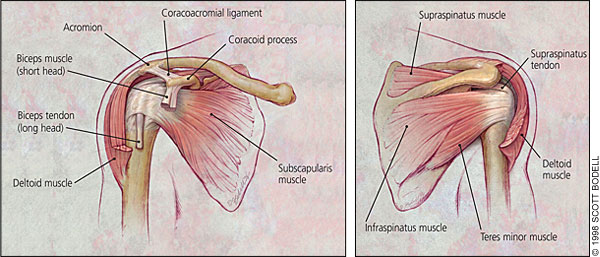

The rotator cuff comprises four muscles—the subscapularis, the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus and the teres minor—and their musculotendinous attachments. The subscapularis muscle is innervated by the subscapular nerve and originates on the scapula. It inserts on the lesser tuberosity of the humerus. The supraspinatus and infraspinatus are both innervated by the suprascapular nerve, originate in the scapula and insert on the greater tuberosity. The teres minor is innervated by the axillary nerve, originates on the scapula and inserts on the greater tuberosity. The subacromial space lies underneath the acromion, the coracoid process, the acromioclavicular joint and the coracoacromial ligament. A bursa in the subacromial space provides lubrication for the rotator cuff (Figure 1).

Functional Anatomy

Understanding the functional anatomy of the rotator cuff assists in understanding its disorders. The rotator cuff is the dynamic stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint. The static stabilizers are the capsule and the labrum complex, including the glenohumeral ligaments. Although the rotator cuff muscles generate torque, they also depress the humeral head. The deltoid abducts the shoulder. Without an intact rotator cuff, particularly during the first 60 degrees of humeral elevation, the unopposed deltoid would cause cephalad migration of the humeral head, with resulting subacromial impingement of the rotator cuff.1 In patients with large rotator cuff tears, the humeral head is poorly depressed and can migrate cephalad during active elevation of the arm. This migration is sometimes evident even on plain radiographs.2

Etiology of Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

The space between the undersurface of the acromion and the superior aspect of the humeral head is called the impingement interval. This space is normally narrow and is maximally narrow when the arm is abducted. Any condition that further narrows this space can cause impingement. Impingement can result from extrinsic compression or from loss of competency of the rotator cuff. Possible causes of impingement are outlined in Table 1.

Normal anatomic variants can cause compression. Three distinct types of acromion (Figure 2) can readily be seen on radiographs, especially on the angled outlet Y view. The type I acromion, which is flat, is the “normal” acromion. The type II acromion is more curved and downward dipping, and the type III acromion is hooked and downward dipping, obstructing the outlet for the supraspinatus tendon.3 Cadaveric studies have shown an increased incidence of rotator cuff tears in persons with type II and type III acromions.2,3

The coracoacromial ligament can also calcify, usually secondary to trauma, and cause impingement. In most cases, acromioclavicular joint arthritis is the culprit, resulting from previous trauma (separations) or, most often, nontraumatic osteoarthritis. The os acromiale (an unfused acromial apophysis) has also been associated with impingement.4

Impingement may occur as a result of loss of competency of the rotator cuff. Pain from any cause, such as overuse or injury, may lead to disuse or weakness of the cuff. The weakness results in cephalad migration of the humeral head due to loss of depressors. This superior migration of the humeral head increases the impingement, thus reinforcing the cycle.

Classification of the Impingement Syndrome

Several classification systems are used with the impingement syndrome. Neer5 divided impingement syndrome into three stages. Stage I involves edema and/or hemorrhage. This stage generally occurs in patients less than 25 years of age and is frequently associated with an overuse injury. Generally, at this stage the syndrome is reversible. Stage II is more advanced and tends to occur in patients 25 to 40 years of age. The pathologic changes that are now evident show fibrosis as well as irreversible tendon changes. Stage III generally occurs in patients over 50 years of age and frequently involves a tendon rupture or tear. Stage III is largely a process of attrition and the culmination of fibrosis and tendinosis that have been present for many years.

History and Physical Examination

Pain, weakness and loss of motion are the most common symptoms reported. Pain is exacerbated by overhead or above-the-shoulder activities. A frequent complaint is night pain, often disturbing sleep, particularly when the patient lies on the affected shoulder. The onset of symptoms may be acute, following an injury, or insidious, particularly in older patients, where no specific injury occurs.

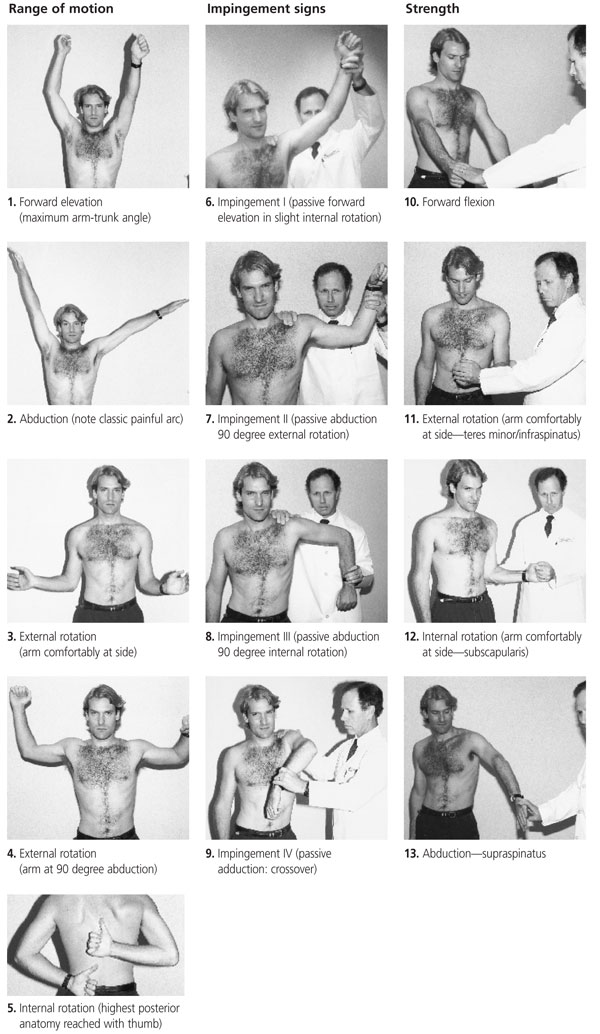

The key feature of the physical examination is an assessment for signs of impingement. All the impingement tests involve moving the shoulder passively (through forward flexion, internal and external rotation with the arm abducted 90 degrees, and adducted) with approximately 5 to 10 lb of force directed inferiorally on the acromion, thus narrowing the subacromial space. The examiner tests to see if pain appears with these maneuvers and disappears when the examiner removes the downward acromial push.6

The shoulder assessment in Figure 3 is a modification of a form developed by the Research Committee of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons.7,8 Since the development of this form, studies on rotator cuff muscles show that the supraspinatus is more effectively tested with the thumb-up position (i.e., “full can”) rather than the thumb-down position as shown in the form and that Gerber's lift-off test recruits the sub-scapularis better than forceful internal rotation does.9 (In Gerber's lift-off test [not depicted], the patient places the hand over the spine posteriorally at the belt line with the palm facing posteriorly. The patient is then instructed to “lift off” the hand in a posterior direction against resistance and this movement is compared with the contralateral arm.)

Diagnostic Testing

Plain radiographs can be useful in depicting anatomic variants or calcific deposits. They are specifically useful in ruling out calcific tendonitis and predisposing factors such as type III acromions or acromioclavicular joint arthritis. The three recommended views are the antero-posterior view with the arm at 30 degrees external rotation, the outlet Y view and the axillary view.10

The outlet Y view is useful because it shows the subacromial space and can differentiate the acromion processes. The axillary view is helpful in visualizing the acromion and the coracoid process, as well as coracoacromial ligament calcifications. The anteroposterior view is also excellent for assessing the glenohumeral joint, subacromial osteophytes and sclerosis of the greater tuberosity.

Ultrasonography and arthrography have been used when rotator cuff tears are suspected. However, arthrography is invasive and expensive. Magnetic resonance imaging, although expensive, provides the best imaging mode for rotator cuff pathology but, ultimately, arthroscopy is the best diagnostic modality.11

Differential Diagnosis

Many conditions can mimic impingement. Calcific tendinitis may occur in patients 30 to 50 years of age. The calcific deposit is usually in the supraspinatus tendon and can be very painful. Acromioclavicular arthritis can be a source of pain by itself, in addition to causing impingement. Radiographs show the degenerative changes. A subluxing or dislocating shoulder can be painful and cause impingement. Impingement or an injury can lead to adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder), a complication arising from pain and disuse. In this condition, the capsule of the joint becomes fibrosed. These disorders may present as shoulder pain and may also be associated with impingement. Table 2 presents a more complete synopsis of the differential diagnosis.

| Problem | Presentation | Laboratory/radiographic findings | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impingement | Positive impingement signs, painful motion, night pain | Radiographs may be normal or may show outlet obstruction (spurs, type 2 or type 3 acromion), aided with lidocaine injection | NSAIDs, rehabilitation, subacromial steroid injection, subacromial decompression |

| Rotator cuff tear | Weakness, atrophy; end result of chronic impingement, frequently precipitated by injury | Radiographs may show decreased subacromial space, osteophytes; MRI shows tears | Rehabilitation, especially in older patients; surgery in younger patients |

| Biceps tendon rupture | Bulge in the distal humerus (“Popeye” muscle), usually precipitated by injury; weakness in the supinators (20% loss), weakness in the elbow flexors (8% loss) | Radiographs normal or same as in impingement | NSAIDs, rehabilitation, repair in younger patients for both strength and cosmesis (competitive body builders) |

| Acute calcific tendinitis | Severe acute shoulder pain, very painful, restricted motion, tenderness on greater tuberosity | Radiographs show calcific deposits | NSAIDs and analgesics, rehabilitation and analgesics, steroid injection (usually), arthroscopic decompression (sometimes) |

| Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | Loss of active and passive range of motion, pain at extremes of patient's motion; usually secondary to pain from a previous shoulder problem | Same as in impingement, tears | NSAIDs, rehabilitation modalities; if no improvement after 18 months, manipulation under anesthesia; most patients respond to a dedicated rehabilitation program |

| AC arthritis | Pain, swelling at AC joint, usually associated with impingement | AC joint narrowing, hypertrophy, spurs | Ice, NSAIDs, steroid injections in AC joint (difficult injection); resect distal clavicle if conservative treatment does not work |

| Glenohumeral arthritis | Chronic pain, loss of motion, crepitus, disuse atrophy | Joint space narrowing, changes in humeral head | NSAIDs, physical therapy, total shoulder arthroplasty in advanced cases |

| Septic arthritis | Acute painful limited motion, fever, chills | Elevated white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, synovial fluid white blood cell count >100,000 per mm3 (10.0 × 109 per L), positive culture and Gram stain; early radiographs normal, later radiographs show erosive changes | Intravenous antibiotics, surgical irrigation |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Usually multiple, small-joint, symmetric | Radiograph shows joint space narrowing, osteoporosis; rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate | NSAIDs, DMARDs, steroid injection |

| Gout | Podagra, monoarthritis | Serum uric acid, crystals in joint fluid | Colchicine, NSAIDs, allopurinol (Purinol, Zyloprim), probenecid (Benemid, Benuryl) |

| Lyme disease | Tick bite, erythema migrans | Lyme titer, characteristic rash | Antibiotics |

| Lupus erythematosus | Multiple joints affected | Antinuclear antibody, erythrocyte sedimentation rate | NSAIDs, antimetabolites |

| Spondylo-arthropathy | Sacroiliac joint | HLA B27 | NSAIDs |

| Avascular necrosis | Predisposing factors such as steroid use, trauma, alcoholism; frequently idiopathic; painful motion | Early radiographs normal; later radiographs show humeral head flattening; proceeds to degenerative arthritis | NSAIDs, physical therapy, hemi- or total shoulder arthroplasty |

| Cervical radiculopathy | Radiating pain below shoulder or to upper back, decreased and painful range of motion in neck, positive Spurling's test,* neurologic changes in arms, normal shoulder examination | Radiographs show degenerative changes in cervical spine; MRI may show compressive radiculopathy | NSAIDs, physical therapy, traction, surgical Decompression |

| Tumor | Mass, history of smoking | Chest radiograph may show Pancoast's tumor | Surgery, chemotherapy |

| Thoracic outlet | Decreased pulses with provocative maneuvers | May require angiography | Surgery |

Treatment

In patients with stage I impingement, conservative treatment is often sufficient. Conservative treatment involves resting and stopping the offending activity. It may also involve prolonged physical therapy. Sport and job modifications may be beneficial. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and ice treatments can relieve pain. Ice packs applied for 20 minutes three times a day may help. A sling is never used, because adhesive capsulitis can result from immobilization.

Once the acute pain resolves, a specific strengthening program for the rotator cuff is recommended for prevention of future injuries. The motions of the rotator cuff that are emphasized for strengthening are internal rotation, external rotation and abduction. It is important to remember that the function of the rotator cuff, in addition to generating torque, is to stabilize the glenohumeral joint; thus, stronger rotator cuff muscles result in better glenohumeral joint stabilization and less impingement. A typical initial exercise program involves the use of 4 to 8 oz weights, with 10 to 40 repetitions performed three to five times a week.

Patients with stage II impingement may require a formal physical therapy program. Isometric stretches are useful in restoring range of motion. Isotonic (fixed-weight) exercises are preferable to variable weight exercises. Thus, the shoulder exercises should be done with a fixed weight rather than a variable weight such as a rubber band. Repetitions are emphasized, and a relatively light weight is used. Sometimes, sports-specific techniques are useful, particularly when strengthening the throwing motion, the serving motion or swimming motions. In addition, physical therapy modalities such as electrogalvanic stimulation, ultrasound treatment and transverse friction massages can also be helpful.

Therapeutic Injections

Therapeutic injections (lidocaine plus a corticosteroid) are useful both because they are therapeutic and also because they can help the physician differentiate impingement from other problems. Indications for therapeutic injections include the following:

Rotator cuff impingement that does not improve with conservative treatment, including NSAIDs and physical therapy.

Older patients with clearly operable lesions, such as subacromial spurs, who are not good surgical candidates. Frequently, older, poor surgical candidates can be helped with periodic injections.

As a diagnostic technique. If a patient fails to improve following a subacromial space injection and has normal radiographs with an ambiguous physical examination, the rotator cuff may not be the problem. Thus, after the injection, repeat impingement testing will verify the diagnosis if the pain is ameliorated.12–14

For temporary pain relief in a patient with an operable lesion.

Although there are several entry points for shoulder injections, the posterior subacromial approach is perhaps the easiest (Figure 4). Furthermore, by angling the needle to the underside of the acromion, the physician can easily verify that the needle is properly positioned and, since the humeral head lies more anteriorally, there is no danger of hitting it. It is important not to inject directly into the tendon and, if resistance to flow is encountered, the needle should be directed away from the site. Some potential weakening of the tendon can occur with injection directly into the rotator cuff. We recommend using 8 to 9 mL of lidocaine (Xylocaine), 1 percent, mixed with 20 mg of triamcinolone (20 mg per mL) or a similar amount of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol), 20 mg per mL, or betamethasone (Celestone), 6 mg per mL. The large volume floods the rotator cuff surface. A 1.5-in, 22-gauge needle usually works well.

Operative Treatment

Not all cuff tears diagnosed clinically, or by arthography or MRI require surgical repair. A rotator cuff tear is not, in itself, an indication for surgery.15,16 In fact, survey studies using MRI have shown a high incidence of unsuspected full or partial tears of the rotator cuff in asymptomatic adults.17,18 Most older patients with impingement and rotator cuff tears actually do well without surgery. However, surgery might be considered in a patient who has failed to improve after six months of conservative treatment or in a patient less than 60 years of age with a debilitating tear that impairs function.

Before the advent of arthroscopy, many of these procedures were done using the standard Neer procedure, which decompressed the rotator cuff by shaving the anterior 2 cm of the underside of the acromion through an open incision. The rotator cuff was entered through a deltoid incision, which disrupted the deltoid attachment and left a scar of up to 5 cm in length. In the appropriate patient, arthroscopic acromioplasty has advantages because the deltoid is not disrupted as much, and the glenohumeral joint can also be examined.2,10,11