Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(7):1611-1616

A more recent article on Bartholin gland cyst and gland abscess is available.

See related patient information handout on Bartholin gland cysts, written by the authors of this article.

Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses are common problems in women of reproductive age. Although the cysts are usually asymptomatic, they may become enlarged or infected and cause significant pain. Often the clinician is tempted simply to lance the cyst or abscess, since this technique can be effective for other common abscesses. However, simple lancing of a Bartholin gland cyst or abscess may result in recurrence. More effective treatment methods include use of a Word catheter and marsupialization, both of which can be performed in the office.

Physicians who provide care for women can expect to see Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses, since these problems develop in approximately 2 percent of all women.1 Bartholin cysts are generally asymptomatic but can cause extreme pain and limitation of activity, usually due to enlargement or infection. If the cyst becomes infected, the abscess can grow rapidly, causing pain and making treatment difficult. A number of proven, office-based options are available for treating Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses. The appropriate choices depend on the age of the patient, the size of the cyst or abscess, and whether it has recurred despite previous treatment. The physician caring for women with Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses should have an understanding of the anatomy of the vulva and Bartholin's glands, the differential diagnosis of cystic vulvar lesions, the many treatment options and their potential complications, the infectious agents found in Bartholin gland abscesses and the indications for excision.

Anatomy

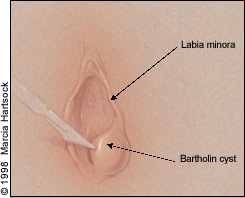

Bartholin's glands are bilateral vulvovaginal bodies located in the labia minora at approximately the 4 and 8 o'clock positions on the posterolateral aspect of the vestibule. The glands are normally about the size of a pea and are composed of cuboidal epithelium. They drain into a duct approximately 2.5 cm long, which is composed mostly of transitional epithelium. The duct exits just external to the hymenal ring into a fold between the hymen and the labium, where the duct lining becomes squamous epithelium. Therefore, either squamous carcinoma or adenocarcinoma can develop in a Bartholin gland. The gland's secretions provide some moisture for the vulva but are not needed for sexual lubrication; thus, removal of a Bartholin gland does not seem to compromise the vestibular epithelium or sexual function.

Differential Diagnosis

A number of vulvar and vaginal lesions can mimic Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses and should be included in the differential diagnosis (Table 1).

| Vulvar lesions |

| Sebaceous cyst |

| Dysontogenetic cyst |

| Hematoma |

| Fibroma |

| Lipoma |

| Hidradenoma |

| Syringoma |

| Endometriosis |

| Myoblastoma |

| Accessory breast tissue |

| Leiomyoma |

| Von Recklinghausen's tumor |

| Adenocarcinoma |

| Vaginal lesions |

| Vaginal inclusion cyst |

| Endometriosis |

| Adenosis |

| Gartner duct cyst |

| Leiomyoma |

| Inguinal hernia |

Sebaceous cysts of the vulva are common and present similarly to sebaceous cysts in other areas. These are epidermal inclusion cysts and are often asymptomatic. If infected, they respond well to simple incision and drainage. Dysontogenetic cysts are benign mucus-containing cysts located in the introitus or labia minora and are probably caused by incomplete separation of the cloaca from the urorectal folds. They contain rectal-like tissue and are usually asymptomatic. Hematomas of the vulva are caused by straddle injuries, sporting injuries, abuse or other trauma.

Fibromas are the most common benign solid tumors of the vulva. Indications for excision include pain, rapid growth and cosmetic concerns. Lipomas can also occur on the labia majora and can grow to an enormous size. Hidradenomas are rare benign tumors that arise on either the labia majora or, less commonly, the labia minora. They should be biopsied if they bleed or removed if they are symptomatic. Other rare vulvar masses include syringomas, vulvar endometriosis, granular cell myoblastomas, accessory breast tissue, leiomyomas and neural sheath tumors of von Recklinghausen's disease (neurofibromatosis).

Cystic lesions can also occur in the vagina and are usually distinguished from Bartholin gland cysts by their anatomic location. In some cases, however, diagnosis can be difficult. Vaginal lesions include inclusion cysts, endometriosis, adenosis and Gartner duct cysts (benign cysts of mesonephric origin usually located on the anterolateral vaginal wall). We have encountered an interesting case in which a patient referred for treatment of a presumed Bartholin gland cyst actually had a painful 3-cm leiomyoma on the right posterolateral vaginal wall, about 1 cm proximal to the hymenal ring. In another case,2 a presumed inguinal hernia was found to be a Bartholin gland cyst. If the diagnosis is in doubt, biopsy or excision of the vulvar or vaginal mass should be performed.

Management of Bartholin Gland Cysts

Normally, the Bartholin's gland cannot be palpated. Bartholin gland cysts develop from cystic dilation of the duct following blockage of the duct orifice. They are generally 1 to 3 cm in size and are usually asymptomatic. The patient may notice a bulge in the labium majus or the cyst may be found during a routine gynecologic examination. When symptoms occur, the patient may report vulvar pain, dyspareunia, inability to engage in sports and pain during walking or sitting. Bartholin gland cysts tend to grow slowly. Since noninfected cysts are usually sterile, routine antibiotic therapy is not necessary.1

Asymptomatic Bartholin gland cysts in patients under age 40 may not require treatment. As discussed below, some clinicians advocate excision of all Bartholin gland cysts in patients over 40 years of age because of the possibility of cancer.1 Various treatment options are available if a cyst causes cosmetic problems or bothersome symptoms. If a patient has a Bartholin gland cyst that ruptures spontaneously, all she may need is hot sitz baths.

Occasionally, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics is indicated if secondary infection develops. Simple lancing and drainage of the Bartholin gland cyst is mentioned here only to discourage its routine use. One author3 reported an 85 percent cure rate using cyst or abscess aspiration in 34 patients after sending the aspirate for culture. We have found, however, that many cysts and most abscesses recur if treated only by aspiration. We often see patients who are referred because multiple incision and drainage procedures have been unsuccessful. Definitive methods of treatment include placing a Word catheter, marsupializing the cyst, performing a “window” procedure, using a carbon dioxide laser, applying silver nitrate to the cyst cavity or excising the entire cyst.

Word Catheter

Placement of a Word catheter (Figure 1) is a simple procedure that can be used to treat a symptomatic Bartholin gland cyst.4 (Catheter is available from Rusch Corporation, 2450 Meadowbrook Pkwy., Duluth, GA 30096; telephone: 800-553-5214.)

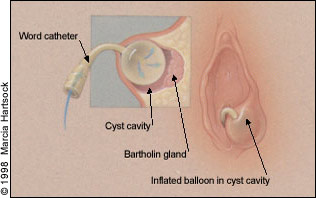

After local anesthesia and sterile preparation with povidone-iodine or a similar solution, a no. 11 scalpel is used to make a stab incision 1.0 to 1.5-cm deep into the cyst, preferably just inside or, if necessary, just outside the hymenal ring (Figure 2). The stab wound should not be made on the outside of the labium, however, since a permanent fistula may develop. A hemostat or similar instrument is inserted to break up any loculations, and then a Word catheter is placed. The Word catheter is a small rubber catheter with an inflatable balloon tip that is inserted into the stab wound after the cyst's contents have been drained. The bulb is inflated with water or lubricating gel, and the free end of the catheter is tucked up into the vagina (Figure 3). (Using water or gel rather than air will prevent premature deflation of the balloon.)

We have found that placing an 18- or 20-gauge needle into the catheter's self-sealing injection port before inserting the catheter into the incision reduces the chance of accidental needle-stick injury. The catheter is left in place for up to four weeks to permit complete epithelialization of the new tract. The patient is asked to undergo pelvic rest until removal of the catheter and is advised to abstain from sexual intercourse. The catheter is removed by deflating the balloon, and over time the resulting orifice will decrease in size and become unnoticeable.

Marsupialization

A marsupialization procedure can be performed if a cyst recurs despite treatment with a Word catheter or if the physician prefers it as a first-line technique.5,6 Marsupialization is a relatively straightforward procedure that can be performed in the office, emergency department or outpatient surgical suite in about 15 minutes, using local anesthesia. After sterile preparation of the cyst and surrounding area, a no. 11 scalpel is used to make a vertical elliptic incision just inside or outside the hymenal ring (Figure 4, left), but not on the outer labium majus. The incision should measure about 1.5 × 1.0 cm and should be deep enough to include both the vestibular skin and the underlying cyst wall (Figure 4, right). An oval wedge of vulvar skin and underlying cyst wall should be removed. The cyst or abscess will drain. Loculations are broken if necessary; the cyst wall is sewn to the adjacent vestibular skin using interrupted 3-0 or 4-0 delayed-absorbable sutures on a small needle (Figure 5). Silver nitrate sticks or direct pressure can be used for hemostasis of the skin edge. The new tract will slowly shrink over time and epithelialize, forming a new duct orifice. The recurrence rate after marsupialization is about 10 percent.1 The instruments used in the marsupialization and Word catheter procedures are listed in Table 2.

| Word catheter | Marsupialization |

|---|---|

| Povidone-iodine solution Anesthetic solution Word catheter 18- or 20-gauge needle and 5 mL-syringe plus water or gel for inflation of catheter tip No. 11 scalpel Hemostat (for breaking up loculations) Culture media for gonorrhea, Chlamydia and routine cultures Silver nitrate sticks Gauze pads | Povidone-iodine solution Anesthetic solution No. 11 scalpel |

| 3-0 or 4-0 delayed-absorbable suture on small cutting needle Small needle driver Scissors Hemostats Forceps Culture media Silver nitrate sticks Gauze pads |

Other Techniques

A variation on the classic marsupialization procedure is a “window operation.” In one series,7 clinicians treated 47 patients with Bartholin cysts or abscesses by making an incision similar in location but larger than that of a marsupialization incision, which resulted in removal of a relatively large, oval piece of the cyst wall. The cyst wall was sewn to the skin of the vestibule using interrupted 2-0 chromic catgut in a similar fashion to the marsupialization procedure. No treatment failures or complications were reported. The authors theorized that the larger opening prevented occlusion of the newly formed orifice, a feature that may make the window operation more advantageous than the marsupialization procedure.

Other techniques include incision of Bartholin gland abscesses followed by curettage of the abscess cavity,8 application of silver nitrate to the cyst or abscess cavity9,10 and use of a carbon dioxide laser.11 One team compared excision with silver nitrate application for the treatment of Bartholin gland abscesses and cysts and concluded that silver nitrate was as effective as excision.9 It would be valuable to compare silver nitrate application with a treatment option less morbid than excision, such as marsupialization or placement of a Word catheter. The carbon dioxide laser is also an effective method of treating Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses.11 We believe, however, that the laser usually offers no advantage over the less expensive and less technically difficult procedures described above.

Excision

A cyst that has recurred several times despite office-based treatment may require excision. Excision of a Bartholin gland cyst is an outpatient surgical procedure that probably should be performed in an operating suite because of the possibility of copious bleeding from the underlying venous plexus (vestibule bulbs). The procedure is usually performed under conduction or general anesthesia and can result in intraoperative hemorrhage, hematoma formation, secondary infection and dyspareunia due to scar tissue formation. Therefore, patients with recurrent Bartholin gland cysts that require excision should be referred to a gynecologist or other physician experienced with this procedure.

The procedures that have been described are safe and effective; however, complications can occur. Septic shock has been reported after drainage of a Bartholin gland abscess.12 Other potential complications include excessive bleeding, cellulitis and dyspareunia.

Management of Bartholin Gland Abscesses

A Bartholin gland abscess can be so painful that the patient is incapacitated. Common symptoms are severe dyspareunia, difficulty in walking or sitting, and vulvar pain. Signs in addition to a large, tender mass in the vestibular area are vulvar erythema and edema. Bartholin gland abscesses usually develop over two to four days and can become larger than 8 cm. They tend to rupture and drain after four to five days. In the past, Bartholin gland abscesses were thought to develop mainly from gonococcal or chlamydial infections. However, Brook13 reported 67 different bacterial isolates similar to the natural vaginal flora in a series of Bartholin gland abscesses. While it remains important to test for gonococcal and chlamydial infection, the polymicrobial nature of these abscesses requires broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage.

Treatment of Bartholin gland abscesses is similar to that of symptomatic cysts. If an abscess points and ruptures spontaneously, the patient may need only sitz baths, antibiotics and pain medication. In fact, it is prudent to treat early abscesses with sitz baths until the abscess points, making incision and definitive treatment easier. Placement of a Word catheter, a marsupialization or “window” procedure, application of silver nitrate to the abscess cavity, carbon dioxide laser excision and surgical excision are all acceptable options for treatment of a Bartholin gland abscess, although excision would not be the primary choice because of the risk of hemorrhage. Cultures for Chlamydia and gonococcal organisms should be obtained and a course of oral broad-spectrum antibiotics prescribed. Diabetic patients need careful observation due to their susceptibility to necrotizing infections, and consideration should be given to inpatient management of these patients.

Adenocarcinoma of Bartholin's Gland

Adenocarcinoma of Bartholin's gland is rare but should be considered in the differential diagnosis of labial masses.14 The incidence is highest among women in their 60s. Symptoms and signs can mimic those of benign Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses, although fixation of the gland to the underlying tissue may be noted. While some authorities have advocated excision of all Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses in women over age 40,1 others have suggested that excision is rarely necessary in these women. In a retrospective cohort study, investigators concluded that the incidence of Bartholin gland cancer in postmenopausal women is so low (0.114 per 100,000 woman-years) that routine excision is unwarranted; instead, women in this age group may benefit from drainage and selective biopsy.15

Since patients with adenocarcinoma of Bartholin's gland may require radical surgery, referral to a gynecologist or gynecologic oncologist familiar with the treatment of this carcinoma may be prudent in older patients with Bartholin gland cysts or abscesses.

Pregnancy

Although none of the treatment methods discussed are contraindicated in pregnant women, the increase in blood flow to the pelvic area during pregnancy may lead to excessive bleeding when Bartholin cysts or abscesses are treated. For this reason, surgical treatment for asymptomatic cysts should probably be withheld until after delivery. If treatment is necessary because a cyst becomes infected or the patient presents with an abscess, local anesthesia is not contraindicated, and most broad-spectrum antibiotics appear safe for use during pregnancy.

Occasionally, patients present with symptomatic Bartholin gland abscesses during labor. In this situation, it seems wise to withhold treatment until after delivery if possible, since an open labial abscess theoretically places the patient at risk for endomyometritis. Unless the abscess obstructs the vagina (soft tissue dystocia), cesarean section is not indicated.