This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(4):1143-1152

See related patient information handout on microscopic hematuria, written by the authors of this article.

In patients without significant urologic symptoms, microscopic hematuria is occasionally detected on routine urinalysis. At present, routine screening of all adults for microscopic hematuria with dipstick testing is not recommended because of the intermittent occurrence of this finding and the low incidence of significant associated urologic disease. However, once asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is discovered, its cause should be investigated with a thorough medical history (including a review of current medications) and a focused physical examination. Laboratory and imaging studies, such as intravenous pyelography, renal ultrasonography or retrograde pyelography, may be required to determine the degree and location of the associated disease process. Cystourethroscopy is performed to complete the evaluation of the lower urinary tract. Microscopic hematuria associated with anticoagulation therapy is frequently precipitated by significant urologic pathology and therefore requires prompt evaluation.

Microscopic hematuria is defined as the excretion of more than three red blood cells per high-power field in a centrifuged urine specimen.1 Because the degree of hematuria bears no relation to the seriousness of the underlying cause, hematuria should be considered a symptom of serious disease until proved otherwise.

The widespread use of dipstick urinalysis in clinical practice and health screening has resulted in increased recognition of microscopic hematuria and has raised concerns about the appropriate diagnostic investigation. The prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria in adult men and postmenopausal women has been reported to range from 10 percent to as high as 20 percent.2–4 Routine screening of all adults for microscopic hematuria with dipstick testing is not currently recommended because of the intermittent occurrence of this finding and the low incidence of significant associated urologic disease.

Detection of Hematuria

DIPSTICK TESTS FOR HEMATURIA

In clinical practice, dipstick urinalysis is the test most commonly used to detect urinary tract disorders in asymptomatic patients. In this test, cellulose strips dipped into a urine specimen record the ability of hemoglobin to catalyze the reaction between hydrogen peroxide and a chromogen. The resulting reaction causes the chromogen to turn green, with the degree of color change directly related to the amount of hemoglobin present in the urine specimen. A spotted pattern to the dipstick indicates the presence of free hemoglobin.5,6

Dipstick testing has been shown to be 91 to 100 percent sensitive and 65 to 99 percent specific for the detection of hemoglobin.7 False-positive test results have been reported in the presence of myoglobinuria and oxidizing contaminants (e.g., hypochlorite, povidone and bacterial peroxidases), contamination of the urine specimen with menstrual blood, and dehydration with elevation of urine specific gravity.1,5 False-negative results have been reported in the presence of reducing agents (e.g., ascorbic acid), a urinary pH of less than 5.1 and dip-sticks that have been exposed to air.1,5

URINE SPECIMEN COLLECTION AND PREPARATIONS

Several factors can influence the microscopic detection of erythrocytes in urine. Procurement of a urine sample using a catheter may cause urethral trauma that results in variable degrees of hematuria. A clean-catch midstream urine specimen should be obtained using aseptic technique to avoid contamination from the external genitalia. The first urine in the morning is typically the best specimen because erythrocytes are heat preserved in acidic and concentrated urine.

A prolonged delay from specimen collection to analysis can result in a false test interpretation. When a urine specimen cannot be examined within one hour of collection, it should be refrigerated to prevent overgrowth of bacteria, changes in urinary pH and disintegration of red and white cell casts. These conditions may occur if the specimen remains at room temperature for a long period.

Standardization of the analysis procedure is also essential to achieve an accurate result. Centrifugation is typically performed on a fixed volume of urine (5 mL) for five minutes at 3,000 rotations per minute, after which the supernatant is poured off and the remaining sediment is resuspended in the centrifuge tube by gently tapping the bottom of the tube. A pipette is used to sample the residual fluid and transfer it to a glass slide; a cover-slip is applied to the slide for the microscopic evaluation.5 The specimen is examined under high magnification (× 400) to determine cell type and distinct morphologic features. Results are recorded as the number of red blood cells per high-power field.

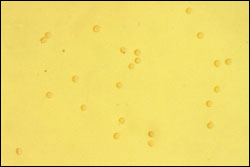

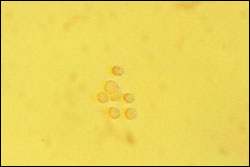

FINDINGS ON MICROSCOPY

Dysmorphic erythrocytes are characterized by an irregular outer cell membrane and suggest hematuria of glomerular origin. Red blood cell casts are also associated with a glomerular cause of hematuria. Acanthocytes, which are ring-formed erythrocytes with one or more membrane protrusions of variable size and shape, may represent an early form of dysmorphic erythrocytes and are a marker for hematuria of glomerular origin.

Erythrocytes of uniform character are classified as isomorphic and suggest hematuria of lower urinary tract origin. Microscopic clots of clumped erythrocytes in urine are also suggestive of lower urinary tract bleeding.

The presence of both dysmorphic and isomorphic erythrocytes in urine represents a mixed morphologic pattern of nonspecific origin.

Diagnosis of Hematuria

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

| Artificial food coloring |

| Beets |

| Berries |

| Chloroquine (Aralen) |

| Furazolidone (Furoxone) |

| Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) |

| Nitrofurantoin (Furadantin) |

| Phenazopyridine (Pyridium) |

| Phenolphthalein |

| Rifampin (Rifadin) |

| Mechanism | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Interstitial nephritis | Captopril (Capoten) |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Chlorothiazide (Diuril) | |

| Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) | |

| Furosemide (Lasix) | |

| NSAIDs | |

| Olsalazine (Dipentum) | |

| Omeprazole (Prilosec) | |

| Penicillins | |

| Rifampin (Rifadin) | |

| Silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) | |

| Papillary necrosis | Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) |

| NSAIDs | |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis | Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) |

| Ifosfamide (Ifex) | |

| Mitotane (Lysodren) | |

| Urolithiasis | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors |

| Dichlorphenamide (Daranide) | |

| Indinavir (Crixivan) | |

| Mirtazapine (Remeron) | |

| Ritonavir (Norvir) | |

| Triamterene (Dyrenium) |

The information obtained in the medical history is used to screen for the multiple potential causes of both glomerular and nonglomerular conditions that can lead to microscopic hematuria (Table 3).11–15 IgA nephropathy (Berger's disease) is the most common cause of glomerular hematuria. Drug-induced glomerular causes of hematuria include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and certain antibiotics associated with analgesic nephropathy and interstitial nephritis (Table 2).9,10

One common nonglomerular medical cause of hematuria is papillary necrosis. This condition should be considered in patients with diabetes mellitus, black patients with sickle cell trait or disease, and patients known to be analgesic abusers. Other common nonglomerular causes of hematuria include urothelial tumors, urolithiasis, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and urinary tract infection.

The physical examination should take into account the multiple potential causes of hematuria and include the following points: evaluation of the cardiovascular system for irregular cardiac rhythm, heart murmur or hypertension; evaluation of the abdomen for organomegaly or flank mass; evaluation of the prostate and external genitalia; and evaluation of the extremities for peripheral edema, petechiae or mottling (Table 4).

| Physical examination finding | Cause of hematuria | |

|---|---|---|

| General (systemic) examination | ||

| Severe dehydration | Renal vein thrombosis | |

| Peripheral edema | Nephrotic syndrome, vasculitis | |

| Cardiovascular system | ||

| Myocardial infarction | Renal artery embolus or thrombus | |

| Atrial fibrillation | Renal artery embolus or thrombus | |

| Hypertension | Glomerulosclerosis with or without proteinuria | |

| Abdomen | ||

| Bruit | Arteriovenous fistula | |

| Genitourinary system | ||

| Enlarged prostate | Urinary tract infection | |

| Phimosis | Urinary tract infection | |

| Meatal stenosis | Urinary tract infection | |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Occupational exposures | |

| Aniline dyes | |

| Aromatic amines | |

| Benzidine | |

| Dietary nitrites and nitrates | |

| Analgesic abuse (e.g., phenacetin) | |

| Chronic cystitis and bacterial infection associated with urinary calculi and obstruction of the upper urinary tract | |

| Urinary schistosomiasis | |

| Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) | |

| Pelvic irradiation | |

LABORATORY TESTS

The initial laboratory studies are determined by pertinent information obtained from the medical history and physical examination. Formal urinalysis is performed to document the degree of hematuria, determine the morphologic features of erythrocytes and evaluate urinary crystals and casts. If pyuria or bacteriuria is present, a urine culture with sensitivity testing should be obtained to rule out infectious urinary tract pathogens. Screening laboratory tests typically consist of coagulation studies, a complete blood count, serum chemistries and serologic studies for glomerular causes of hematuria as directed by the medical history.

Further urologic evaluation is warranted if more than three red blood cells per high-power field are found on at least two of three properly collected urine specimens or if high-grade microscopic hematuria (more than 100 red blood cells per high-power field) is found on a single urinalysis.17 The only exceptions are children with persistent microscopic hematuria without proteinuria, in whom the most likely diagnoses include thin glomerular basement membrane nephropathy, idiopathic hypercalciuria, IgA nephropathy and Alport's syndrome.

RADIOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION

The initial radiographic study is intravenous pyelography (IVP), or excretory urography. The purpose of the study is to obtain an anatomic and functional evaluation of the upper and lower urinary tract. Before IVP is performed, the collected urine specimen should undergo microscopic examination to exclude an infectious cause of hematuria. Some centers use renal ultrasonography as an initial test to avoid exposing patients to intravenous contrast media; however, subtle findings in the renal collecting system may be difficult to detect by ultrasonography alone.

Risk factors for contrast uropathy have been described (Table 6).18 Because preexisting renal insufficiency is the most important risk factor for renal failure, the serum creatinine concentration should always be measured before any contrast examination is performed. Early studies reported a 4.7 percent overall incidence of adverse reactions to conventional ionic high-osmolar contrast media.19 Although most of these reactions were considered minor, true anaphylactic reactions have been described. The incidence of death after the intravenous administration of conventional contrast media has been reported to be one case per 40,000 contrast-material injections.19 Newer, non-ionic low-osmolar contrast media are associated with fewer adverse effects than traditional, less expensive, ionic high-osmolar agents.20

| Dehydration | |

| Diabetes with azotemia | |

| Cardiac decompensation | |

| History of allergy | |

| Asthma | |

| Hay fever | |

| Seafood allergy | |

| Others, including allergic reactions to antibiotics | |

| Previous reaction to contrast media | |

| Renal insufficiency | |

Metformin (Glucophage) is an oral antihyperglycemic agent commonly used in the management of type 2 diabetes (formerly termed non–insulin-dependent diabetes). This drug is eliminated primarily by the kidneys. [ corrected] Because of potential exacerbation of acute renal failure and lactic acidosis, metformin should be discontinued at the time of radiologic studies involving intravascular administration of iodinated contrast materials and withheld for 48 hours subsequent to the procedure. It should be reinstituted only after renal function has been reevaluated and found to be normal.21

With excretory urography, tomography is typically performed to increase recognition of renal masses, fine renal calcifications and paranephric structures. Oblique images are obtained to assist in evaluation of ureteral lesions, differentiation of extrinsic and intrinsic renal or ureteral masses and visualization of the posterolateral aspect of the bladder. Delayed images are helpful in cases of obstruction in which the nephrogram phase is seen on IVP but the collecting system is not yet visualized.18

If the use of intravenous contrast material is contraindicated or if incomplete visualization of the lower urinary tract occurs, retrograde pyelography should be performed. Typically, the combination of retrograde pyelography and ultrasonography is employed to increase sensitivity in the detection of solid renal masses. However, renal ultrasonography cannot detect the subtle mucosal abnormalities that occur with transitional cell carcinoma or small, echogenic ureteral calculi. Compared with renal ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) is more sensitive in detecting renal masses and subtle filling defects of the renal collecting system.22 Recently, unenhanced helical CT scans have provided accurate evaluation of patients with acute flank pain through the precise determination of calculus size and location.23 Despite advancements in radiographic imaging, the role of CT or ultrasonography as the primary imaging modality in the work-up of microscopic hematuria has not been established.

LOWER URINARY TRACT INVESTIGATION

Whereas radiographic imaging allows evaluation of the upper urinary tract, cystourethroscopy provides definitive evaluation of the lower urinary tract. In addition to direct visualization of the urethra, prostate and bladder, washings and biopsies of suspicious bladder lesions can be performed during cystourethroscopy.

Cytology obtained from washings is useful in detecting poorly differentiated sessile and in situ bladder lesions. With in situ bladder cancer, the results of cytologic analysis are often positive before lesions are seen with cystoscopy.1

OTHER INVESTIGATIONS

When no cause for microscopic hematuria is found with cystourethroscopy and appropriate radiographic imaging, further studies may be considered. These studies include CT scanning, renal angiography and flexible ureterorenoscopy. No consensus has been reached on the indications for renal biopsy in patients with hematuria, but this procedure may be indicated to rule out glomerular causes of hematuria.1 Despite a complete and exhaustive work-up, no specific cause is identified in approximately 20 percent of patients with microscopic hematuria.24

Molecular markers recently introduced into clinical practice to assist with the follow-up evaluation of urothelial carcinomas have yet to be labeled for the evaluation of hematuria. The two assays currently labeled for clinical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are the bladder tumor antigen (BTA) test and the nuclear matrix protein (NMP-22) test.17,25 The BTA test is a latex agglutination assay for the qualitative detection of a basement membrane antigen in a voided urine specimen. The NMP-22 test involves the quantitative detection of a specific nuclear matrix protein in a voided urine specimen. Although these assays offer great potential for the early detection of recurrent bladder carcinoma, their role in the evaluation of hematuria is still uncertain.

Special Considerations

HEMATURIA DURING ANTICOAGULATION

Microscopic hematuria is commonly encountered in patients taking anticoagulant drugs. Although it may be easy to attribute this hematuria solely to anticoagulation therapy, significant urologic causes have been reported in 13 to 45 percent of such patients.27,28 Current recommended anticoagulation schedules do not predispose patients to hematuria.27 The most common causes of anticoagulant-associated hematuria include BPH, inflammatory conditions, urolithiasis, papillary necrosis and cancers of the upper and lower urinary tract.

HEMATURIA FOLLOWING EXERCISE

Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria resulting from strenuous exercise has been well documented in association with a variety of contact and noncontact sports activities.12–14 The degree of hematuria is believed to be related to the intensity and duration of exercise.12 Although exercise-induced hematuria is typically a benign, self-limited process, coexisting urinary tract pathology may exist and must be carefully excluded.

Exercise-induced microscopic hematuria almost always resolves within 72 hours of onset in patients who do not have underlying urinary tract abnormality. However, if the hematuria is present on repeat urinalysis after 72 hours of rest, further urologic evaluation may be indicated.

Final Comment

Asymptomatic microscopic hematuria is commonly nephric in origin, whereas gross hematuria is often uroepithelial in origin. Gross, painless hematuria is often the first manifestation of a urothelial tumor. However, the degree of hematuria bears no relation to the seriousness of the underlying disease. Consequently, the microscopic finding of blood in the urine should be considered a serious symptom until significant pathology has been excluded.

Phase contrast microscopy is currently the best initial method of documenting microscopic hematuria. The evaluation often includes intravenous pyelography, cystourethroscopy and urinary cytology.

Unfortunately, consensus is lacking regarding the management of persistent asymptomatic microscopic hematuria of unknown etiology. Recommended surveillance schedules for patients with a previous negative evaluation for unexplained microscopic hematuria include urinalysis and voided urinary cytology annually until the hematuria resolves, or for up to three years if microscopic hematuria persists. Any significant increase in the degree of microscopic hematuria (more than 50 red blood cells per high-power field), an episode of gross hematuria or the new onset of irritative voiding symptoms in the absence of infection warrants a complete reevaluation.17

Additional large population-based studies of the prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria and its relationship with age and sex are needed before definitive recommendations can be formalized to practice guidelines.