Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2109-2118

Hip pain in athletes involves a wide differential diagnosis. Adolescents and young adults are at particular risk for various apophyseal and epiphyseal injuries due to lack of ossification of these cartilaginous growth plates. Older athletes are more likely to present with tendinitis in these areas because their growth plates have closed. Several bursae in the hip area are prone to inflammation. The trochanteric bursa is the most commonly injured, and the lesion is easily identified by palpation of the area. Iliotibial band syndrome presents with similar lateral hip pain and may be identified by provocative testing (Ober's test). A methodical physical examination that specifically tests the various muscle groups that move the hip joint can help determine a more specific diagnosis for the often vague complaint of hip pain. A number of hip conditions are more prevalent in athletes of certain ages. Transient synovitis is a common diagnosis in the very young, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease causes bony disruption of the femoral head in prepubescents, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis is seen most commonly in obese adolescent males. Femoral neck stress fractures are seen in adult athletes, especially those involved in endurance sports, and can progress to necrosis of the femoral head if not found early. Older athletes may be limited by degenerative joint disease but nonetheless should be encouraged to stay active.

Athletes in certain sports are particularly prone to hip injury, especially those involved in track or other running sports, soccer and dancing.1 Any athlete, however, is at risk for hip injury from trauma or overuse.

Anatomy

BONES

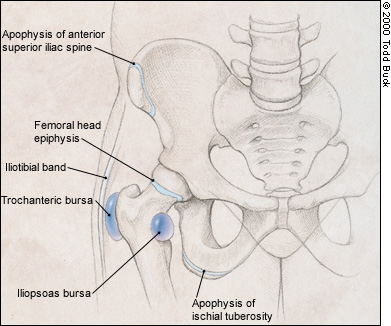

The pelvic component of the hip joint is called the acetabulum, which has contributions from the ischium, ilium and pubis. The acetabulum and the femoral head form the ball-and-socket hip joint. Several areas of the pelvis and the femur are likely to sustain injuries. In younger patients, nonossified bone present at growth plates such as the femoral head epiphysis and the anterior superior iliac spine apophysis is susceptible to injury until the skeleton matures (Figure 1). Maturation of these growth plates varies by site and among patients.

Usually, the last area to mature is the anterior superior iliac spine apophysis, which may be susceptible to injury up to age 25.2 Active young adults who are skeletally mature are at increased risk for stress fracture of the femoral neck.3 Older adults are at risk for degenerative arthritis4 and fracture of the femur and pelvis.

MUSCLES

A large number of muscles coordinate to enable the hip to move through a wide range of motion. These muscles can be divided into groups according to the motion that they are most involved with. Hip flexion is performed by the iliopsoas and a group of muscles commonly referred to as the quadriceps, while hip extension is primarily the function of the hamstring group. Other muscles serve to perform hip adduction, abduction, and internal and external rotation. It is helpful to have a clinical anatomy reference handy when evaluating sport injuries in order to more readily identify specific muscle or tendon injuries. Pain on passive stretching or active motion in a particular direction will often help to identify an injury.

NERVES

The two nerves most likely to cause pain or numbness around the hip are the sciatic and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves. The sciatic nerve includes motor and sensory components that originate from the L4, L5, S1, S2 and S3 nerve roots. It passes through the sciatic notch, where it is susceptible to compression by the piriformis muscle (Figure 2a).5 Patients typically complain of a dull ache in the buttock that may radiate down the posterior thigh. This pain may be difficult to distinguish from radicular pain caused by nerve root compression in the lumbosacral spine. Imaging studies of the spine may be needed to differentiate the two conditions. Females are more commonly affected by piriformis syndrome. Some authors have cited a 6:1 female-to-male incidence.1

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is a sensory nerve. It can be compressed as it passes under the inguinal ligament, especially in obese patients and those with tight-fitting clothing or belts. Known as meralgia paresthetica, this condition causes patients to complain of numbness or pain over the anterolateral thigh (Figure 2b).6

BURSAE

Bursae prevent excessive friction of soft tissue over bony prominences during motion. They may become inflamed and cause “snapping” or pain as the result of repetitive activities or direct trauma. The trochanteric bursa is located lateral to the greater trochanter and is the most commonly injured bursa in the hip. The iliotibial band and gluteus muscles pass over this area (Figure 1).

Falls onto the lateral hip and overuse injuries (especially common in runners and dancers) are the most common causes of trochanteric bursitis. After passing over the greater trochanter, the iliotibial band inserts at the knee on the lateral aspect of the tibia, so patients with iliotibial band syndrome may also complain of lateral knee pain. Steroid injection into the trochanteric bursa may be helpful in addition to icing, anti-inflammatory medication and avoidance of excessive training or overuse.

Another commonly injured bursa is one overlying the ischial tuberosity (Figure 1). A fall on the buttock is the most common cause. The differential diagnosis includes a hamstring strain, an apophysitis or even an avulsion fracture in a skeletally immature athlete.

Less commonly injured is the iliopsoas (iliopectineal) bursa, which cushions the iliopsoas hip flexor muscle as it sweeps over the femoral head and inserts on the lesser trochanter. Patients with an inflamed iliopsoas bursa usually complain of anterior groin pain, which is worse with resisted hip flexion.

NONMUSCULOSKELETAL STRUCTURES

Pathology associated with male and female sexual organs, the intestinal tract, the urinary tract and vascular structures can occasionally lead to symptoms referred to the hip. These etiologies should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any hip complaint without obvious musculotendinous or bony origin, or when therapy does not produce the expected results.

Evaluation of the Athlete with Hip Pain

HISTORY

The age of the patient may suggest different diagnostic possibilities. As mentioned before, younger athletes are more prone to apophyseal injuries. Avulsion fractures are also more likely in skeletally immature patients. Bursitis and muscle strains are more likely to be seen in skeletally mature active young adults. Degenerative arthritis becomes more common with advancing age and is seen primarily in older adults.

For all age groups, an accurate diagnosis depends on a careful history. Patients whose hip pain is caused by pathology in other organs may have other associated symptoms. Unexplained weight loss, fever and night sweats indicate the possibility of a systemic inflammatory process. Genitourinary and abdominal symptoms likewise may indicate that the pathology is located in one of these areas instead of the hip. A careful search for these symptoms is indicated for patients with a history of disease in these systems, as well as for patients who do not have findings consistent with musculoskeletal disease.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination of the hip is similar for athletes of all ages. Using a stepwise approach, including observation, palpation, and testing for range of motion and strength, will help ensure that important findings are not missed. The patient may have on underwear for most of the examination. Covering the patient's genitals during the examination and using a sheet, especially while testing range of motion, will also help the patient feel more comfortable.

Observation. A limited functional evaluation includes determining whether the affected leg can bear weight. If it can, important points to observe include the patient's posture, gait and ability to transfer independently from standing to sitting to lying down, and then back to standing.

If the patient is able to stand erect, the examiner can estimate the height symmetry of the iliac crests by resting his or her hands on the iliac wings. If the crests are asymmetric or the patient is unable to stand, the next step is to compare leg lengths: the distance between the anterior superior iliac spine and the medial malleolus of each leg (Figure 3). Leg length discrepancies have been implicated in a number of musculoskeletal hip and leg injuries. Differences greater than 2 cm may merit correction with heel lifts.7

Palpation. Palpation can be performed with the patient standing or lying down. Careful palpation of each muscle group in the area of the symptoms may help to localize vague complaints to a specific structure. In particular, palpation can identify tenderness over the sites of muscle attachment to bone and the bursae.

Range of Motion. Normal ranges of motion are dependent on the patient's stage of skeletal development, with the range tending to decrease as age increases. Decreased range of motion on the side of the affected hip should heighten the suspicion of an underlying injury. Specific injuries may be suggested by certain defects in range of motion (Table 1).8 Passive and active motion should be assessed—that is, motion produced by the examiner and by the patient.

Muscular Strength Testing. Muscle strength should be tested for the affected hip and the unaffected one to enable the physician to compare strength and detect subtle deficits. Hip flexion strength is best tested with the patient in a sitting position, lifting against the examiner's hand (Figure 4). External and internal rotation also can be evaluated in this position, with the examiner providing resistance against the patient's lower leg (Figures 5 and 6). Abduction and adduction are best tested with the patient supine and the examiner providing resistance against the medial and lateral side of the knee (Figures 7 and 8). Extension strength is best tested with the patient prone and the examiner applying resistance against the lower leg (Figure 9). While the piriformis is an external rotator of the hip, it is best tested with the patient supine. Patients with the piriformis syndrome will have pain with passive internal rotation and palpation of the sciatic notch (Figure 10), as well as with active external rotation.

Another common problem that merits specific testing is the iliotibial band syndrome. Symptomatic patients complain of pain over the lateral aspect of the hip and may feel snapping at the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter with flexion and extension. Ober's test is done to check specifically for iliotibial band syndrome (Figure 11). The patient should be able to drop the affected leg to the table without discomfort while lying on the unaffected side. Iliotibial band syndrome is indicated if the maneuver causes pain along the lateral side of the thigh.

Radiology

While prospective studies have provided guidelines that help decide who should have radiologic evaluation of the ankle9 and knee,10 no such guidelines exist for the hip. The authors recommend obtaining anteroposterior and frog leg lateral hip radiographs of all acutely injured patients with painful gaits, inability to bear weight, point tenderness at a site of muscular insertion, or a markedly reduced range of motion.

For patients with chronic symptoms, the decision to perform radiographs and other special tests depends on the severity of the symptoms and the differential diagnosis. For the large majority of patients with suspected musculotendinous injury, an initial trial of conservative therapy is reasonable, with radiographs reserved for those who do not respond to treatment. Bone scans, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated for certain conditions.

Age-Specific Hip Problems

The differential diagnosis for patients with hip symptoms can be grouped by skeletal maturity. Descriptions of each diagnosis, history, physical findings, differential diagnosis, radiographic testing, treatment options are outlined in Table 1. Some diagnoses may be found in more than one group.

| Diagnosis | History | Physical findings | Differential diagnosis | Special tests | Treatment | Referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease | Insidious onset (1 to 3 months) of limp with hip or knee pain | Limited hip abduction, flexion, and internal rotation | Juvenile arthritis, other inflammatory conditions of the hip | Normal CBC and ESR, plain films positive (early with changes in the epiphysis, later with flattening of the femoral head) | Maintain ROM, follow position of femoral head in relation to acetabulum radiographically | Orthopedic surgery |

| Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Acute (< 1 month) or chronic (up to 6 months) presentation; pain may be referred to knee or anterior thigh | Pain and limited internal rotation, leg more comfortable in external rotation; chronic presentation may have leg length discrepancy | Muscle strain, avulsion fracture | Plain films show widening of epiphysis early, later slippage of femur under epiphysis | Non-weight bearing, surgical pinning | Urgent orthopedic surgery with acute, large slips |

| Avulsion fracture | Sudden, violent muscle contraction; may hear or feel a “pop” | Pain on passive stretch and active contraction of involved muscle; pain on palpation of involved apophysis | Muscle strain, slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Plain films; if these are negative, CT or MRI | Rehabilitation program of progressive increase in ROM and strengthening8 | Orthopedic surgery if > 2 cm displacement |

| Hip pointer | Direct trauma to iliac crest | Tenderness over iliac crest, may have pain on ambulation and active abduction of hip | Contusion, fracture | Plain films if suspect fracture | Rest, ice, NSAIDs, local steroid and anesthetic injection for severe pain, gradual return to activities with protection of site | Consider PT |

| Contusion | Direct trauma to soft tissue | Pain on palpation and motion, ecchymosis | Hip pointer, fracture, myositis ossificans | Plain films negative | Rest, ice, compression, static stretch, NSAIDs | Consider PT |

| Myositis ossificans | Contusion with hematoma approximately 2 to 4 weeks earlier | Pain on palpation; firm mass may be palpable | Contusion, soft tissue tumors, callus formation from prior fracture | Radiograph or ultrasound examination reveals typical calcified, intramuscular hematoma | Ice, stretching of involved structure, NSAIDs; surgical resection after 1 year if conservative treatment fails | Consider PT; orthopedic surgery if resection needed |

| Femoral neck stress fracture | Persistent groin discomfort increasing with activity, history of endurance exercise, female athlete triad (eating disorder, amenorrhea, osteoporosis) | ROM may be painful; pain on palpation of greater trochanter | Trochanteric bursitis, osteoid osteoma, muscle strain | Plain films may show cortical defects in femoral neck (superior or inferior surface); bone scan, MRI, CT may also be used if plain films are negative and diagnosis is suspected | Inferior surface fracture: no weight bearing until evidence of healing (usually 2 to 4 weeks) with gradual return to activities; superior surface fracture: ORIF | Orthopedic surgery for ORIF |

| Osteoid osteoma | Vague hip pain present at night and increased with activities | Restricted motion, quadriceps atrophy | Femoral neck stress fracture, trochanteric bursitis | Plain films; if these are negative and symptoms persist, MRI or CT | Surgical removal if unresponsive to medical therapy with aspirin or NSAIDs | Orthopedic surgery |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Lateral hip, thigh or knee pain, snapping as iliotibial band passes over the greater trochanter | Positive Ober's test | Trochanteric bursitis | — | Modification of activity, footwear; stretching program, ice massage, NSAIDs | Consider PT |

| Trochanteric bursitis | Pain over greater trochanter on palpation, pain during transitions from standing to lying down to standing | Pain on palpation of greater trochanter | Iliotibial band syndrome, femoral neck stress fracture | Plain films, bone scan, MRI negative for bony involvement | Ice, NSAIDs, stretching of iliotibial band, protection from direct trauma, steroid injection | Consider PT |

| Avascular necrosis of the femoral head | Dull ache or throbbing pain in groin, lateral hip or buttock, history of prolonged steroid use, prior fracture, slipped femoral capital epiphysis | Pain on ambulation, abduction, internal and external rotation | Early degenerative joint disease | Plain films, MRI | Protected weight bearing, exercises to maximize soft tissue function (strength and support), total hip replacement | PT, orthopedic surgery |

| Piriformis syndrome | Dull posterior pain, may radiate down the leg mimicking radicular symptoms, history of track competition or prolonged sitting | Pain on active external rotation, passive internal rotation of hip and palpation of sciatic notch | Nerve root compression, stress fractures | EMG studies may be helpful, MRI of lumbar spine if nerve root compression is suspected | Stretching, NSAIDs, relative rest, correction of offending activity | Consider PT |

| Iliopsoas bursitis | Pain and snapping in medial groin or thigh | Reproduce symptoms with active and passive flexion/extension of hip | Avulsion fracture | Plain films are negative | Iliopsoas stretching, steroid injection | Consider PT |

| Meralgia paresthetica | Pain or paresthesia of anterior or lateral groin and thigh | Abnormal distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve on sensory examination | Other causes of peripheral neuropathy | Nerve conduction velocity testing may be helpful | Avoid external compression of nerve (clothing, equipment, pannus) | — |

| Degenerative arthritis | Progressive pain and stiffness | Reduction in internal rotation early, in all motion later; pain on ambulation | Inflammatory arthritis | Plain films help with diagnosis and prognosis | Maximizing support and strength of soft tissues, ice, NSAIDs, modification of activities, cane, total hip replacement | PT, orthopedic surgery |

PREPUBESCENT

Transient synovitis is the most common cause of hip pain in children. Many children will have a history of recent minor trauma, although this is obviously nonspecific in this age group. Transient synovitis typically affects young children who present with a limp of acute onset. On examination, the child will often refuse to use the affected leg and will have pain with any motion. Most children rapidly improve over two to three days, and more serious conditions such as a septic arthritis or juvenile rheumatoid arthritis should be considered if this rapid improvement is not seen.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that affects the femoral head. The disease is more common in males (with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1) and has a peak incidence in the four-to-eight-year-old age range but should be considered in any prepubescent child who has hip or knee pain, or who develops a limp.11

Patients with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease are unlikely to have a fever and should have a normal white blood cell (WBC) count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). Abnormalities in these parameters should increase suspicion of a septic joint or other inflammatory process. Radiographic studies will show bony disruption or sclerosis of the femoral head in classic cases, but films can appear normal. Bone scans or MRI may be useful if plain films are unremarkable.

ADOLESCENCE

Another age-specific condition that affects the femoral head is slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Failure of the cartilaginous growth plates allows the epiphysis to slip on the femoral neck. There may be a history of a recent sport injury, but again this is nonspecific and common for this age group. It is seen more frequently in 11-to-14-year-olds. The etiology is likely multifactorial. However, obesity and male sex increase the risk.12 Slipped capital femoral epiphysis may be acute or chronic (Table 1). Missing this diagnosis increases the risk for progression of the slip and increases the likelihood of later development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head and early degenerative arthritis.

Patients with confirmed or suspected slips should not be permitted to bear weight, and referral to an orthopedic surgeon should be considered. Unlike patients with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, in whom surgical treatment is quite controversial, patients with slip often require pinning of the slipped bone fragment. Up to 30 percent of cases are bilateral, either at the time of presentation or later.13 Until the epiphyses close, any patient with a confirmed slip will need to have the opposite leg monitored closely.

YOUNG ADULT

The young adult athlete with hip symptoms has the longest list of possible diagnoses. This group is more likely to be involved in high-intensity sports that may involve risk of substantial trauma. Avulsion fractures, muscle contusions, femoral neck stress fractures, osteoid osteoma, iliotibial band syndrome and a host of other conditions are possible (Table 1).

The most critical diagnosis to make early in this group is the femoral neck stress fracture. This is usually found in the patient who is involved in an endurance sport. Another group at increased risk is women with the female athlete triad (amenorrhea, eating disorder and osteoporosis).14 The typical history in these cases is progressively increasing pain with exercise that eventually becomes pain at rest. Femoral neck stress fractures can progress to unstable fractures and are at increased risk for avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Bone scans are a useful “negative” test because they are up to 100 percent sensitive15 for stress fractures of the femoral neck. Positive scans are nonspecific and may require MRI or other imaging to be certain of a diagnosis.

Osteoid osteoma is a benign bone tumor of adolescents and young adults often discovered incidentally on a hip film. Treatment is with aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). In fact, the pain of osteoid osteoma is characteristically relieved by aspirin. For severe, refractory cases, surgical excision may be used.

OLDER ADULT

Older athletes are at much greater risk of developing degenerative arthritis in the hip joint, which is a major cause of disability in the elderly. Several factors probably predispose patients to this condition, including previous acute or chronic injuries to the structures around the hip, obesity and genetic factors.16

The role of recreational athletics in the development of degenerative arthritis of the hip is controversial.17,18 The health benefits of being physically active likely outweigh any possible increased risk. Lack of activity places older adults at increased risk of obesity, with a resultant elevated risk of degenerative arthritis.