Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(9):2015-2026

See related patient information handouts on taking care of burns and preventing burns, written by the authors of this article.

Burns often happen unexpectedly and have the potential to cause death, lifelong disfigurement and dysfunction. A critical part of burn management is assessing the depth and extent of injury. Burns are now commonly classified as superficial, superficial partial thickness, deep partial thickness and full thickness. A systematic approach to burn care focuses on the six “Cs”: clothing, cooling, cleaning, chemoprophylaxis, covering and comforting (i.e., pain relief). The American Burn Association has established criteria for determining which patients can be managed as outpatients and which require hospital admission or referral to a burn center. Follow-up care is important to assess patients for infection, healing and ability to provide proper wound care. Complications of burns include slow healing, scar formation and contracture. Early surgical referral can often help prevent or lessen scarring and contractures. Family physicians should be alert for psychologic problems related to long-term disability or disfigurement from burn injuries.

Burns can be devastating injuries that result in death or lifelong scarring, disfigurement and dysfunction. Burn injuries are the third leading cause of accidental death in the United States (after incidents involving motor vehicles and firearms). Each year, more than 1 million persons in this country seek medical care for burns. More than 95 percent of these patients can be managed on an ambulatory basis.1,2

Ambulatory management of burns is divided into acute treatment and follow-up care. Acute management includes measures to minimize further damage to patients presenting with recently sustained burns, identifying patients requiring hospitalization and implementing measures to promote healing, prevent infection and relieve pain. During follow-up care, the focus shifts to limiting disfigurement from scarring and dysfunction from contractures. Although most patients with burns can be managed by family physicians, some require surgical referral for skin grafting and scar rehabilitation.

Acute Management of Burns

It is of paramount importance to determine whether a patient with a burn injury should be hospitalized for hydration and burn care or whether ambulatory management appears feasible. Classification of burns as minor, moderate or major facilitates hospitalization decisions. Proper burn classification requires accurate determination of the depth and extent of the wound(s), as well as consideration of critical issues such as skin thickness, burn location and comorbid conditions.

DEPTH OF A BURN

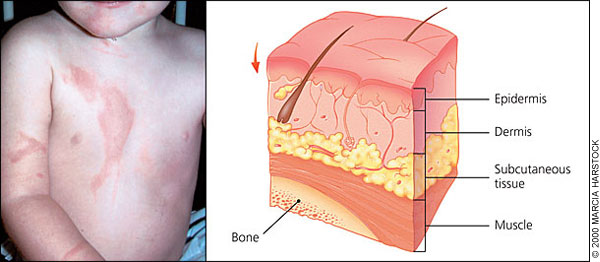

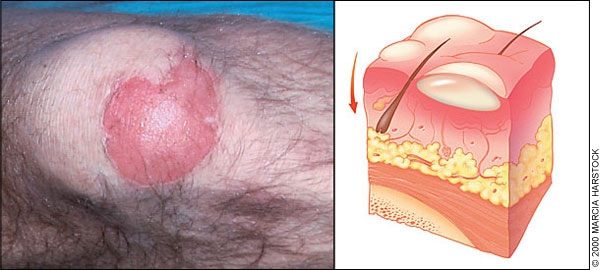

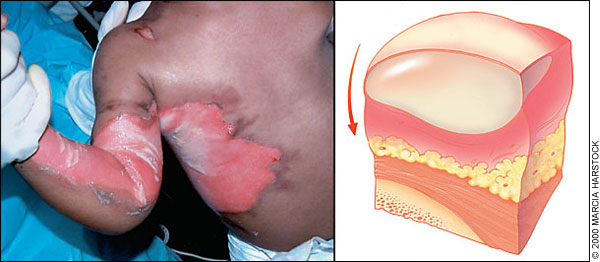

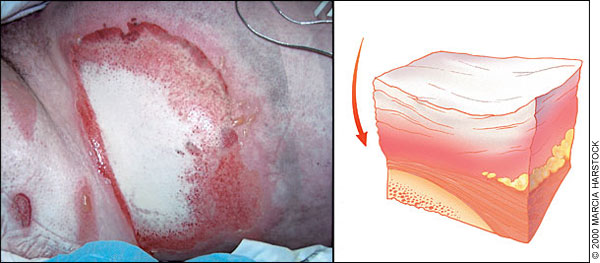

The traditional classification of burns as first, second or third degree is being replaced by the designations of superficial (Figure 1), superficial partial thickness (Figure 2), deep partial thickness (Figure 3) and full thickness (Figure 4).2 Burn depth has an impact on healing time, the need for hospitalization and surgical intervention, and the potential for scar development. Although accurate classification is not always possible initially, the causes and physical characteristics of burns are helpful in categorizing their depth (Table 1).2–4

| Classification | Cause | Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Sensation | Healing time | Scarring | ||

| Superficial burn | Ultraviolet light, very short flash (flame exposure) | Dry and red; blanches with pressure | Painful | 3 to 6 days | None |

| Superficial partial-thickness burn | Scald (spill or splash), short flash | Blisters; moist, red and weeping; blanches with pressure | Painful to air and temperature | 7 to 20 days | Unusual; potential pigmentary changes |

| Deep partial-thickness burn | Scald (spill), flame, oil, grease | Blisters (easily unroofed); wet or waxy dry; variable color (patchy to cheesy white to red); does not blanch with pressure | Perceptive of pressure only | More than 21 days | Severe (hypertrophic) risk of contracture |

| Full-thickness burn | Scald (immersion), flame, steam, oil, grease, chemical, high-voltage electricity | Waxy white to leathery gray to charred and black; dry and inelastic; does not blanch with pressure | Deep pressure only | Never (if the burn affects more than 2 percent of the total surface area of the body) | Very severe risk of contracture |

Differentiating a deep partial-thickness burn from a full-thickness burn can be quite difficult initially.2,5,6 Revisions of burn-depth estimations are often necessary in the first 24 to 72 hours5 and may be required through the first two or three weeks.2 For instance, although a full-thickness burn typically has a white or charred appearance, it can be red after a scald injury. It is also possible to have a full-thickness burn underneath a blister, which is usually a characteristic feature of a partial-thickness burn.3 Furthermore, thin skin sustains deeper burn injuries than may be suggested by the initial appearance of the wound.5 Thin skin is common on the volar surface of the arms and on the medial thigh, perineum and ears. All skin can be presumed to be thin in children younger than five years and in adults older than 55 years.5 It is best to assume that there are no shallow burns in these age groups.7

EXTENT OF A BURN

The extent of a burn is expressed as the total percentage of body surface area (TBSA) affected by the injury. Accurate estimation of the TBSA of a burn is essential to guide management.

Multiple methods have been developed to estimate the TBSA of burns. These methods are not used for superficial burns. The best known method, the “rule of nines,” is appropriate for use in all adults and when a quick assessment is needed for a child.2

The surface area of a patient's palm can also be used to estimate the extent of small or patchy burns. Classically, the palm has been considered to represent 1 percent of the TBSA.2,6 However, a recent study demonstrated that the palm more accurately represents 0.4 percent of the TBSA, and the entire hand represents 0.8 percent of the TBSA.9

INPATIENT TREATMENT AND BURN UNIT REFERRAL

Patients considered to have moderate burns based on the grading system developed by the American Burn Association (ABA) should be admitted for intravenous hydration and surgical care of their wounds (Table 2).6,10 Because of the initial difficulties in differentiating deep partial-thickness burns from full-thickness burns, family physicians should strongly consider obtaining a surgical consultation for what appears to be a deep partial-thickness burn affecting more than 3 percent TBSA.4

Pulmonary insufficiency is responsible for more than 75 percent of fire-related deaths.1 Because of the possibility of progressive edema, patients with suspected inhalation injury should be observed for at least 12 to 24 hours.6,11 Historical or physical findings that raise concern about inhalation injury include coughing, wheezing, dyspnea, facial burns, sooty mucus and laryngeal edema.4

Patients at risk for inhalation injury should also be checked for carbon monoxide poisoning. An arterial carboxyhemoglobin level of greater than 10 percent tends to indicate carbon monoxide exposure. Hyperbaric oxygen is the treatment.13

Hospital admission is necessary for patients who have circumferential partial-thickness or full-thickness burns, patients who have burn injury and are considered to be predisposed to infection (e.g., those with diabetes), and patients who have sustained a high-voltage electrical injury.14 Cardiac arrhythmias can occur up to 72 hours after high-voltage electrical injury.15 Nonspecific changes in ST-T waves are the most common abnormalities noted on electrocardiograms (ECGs) obtained subsequent to electrical injuries. Observation is warranted until the ECG becomes normal.6

Children with burns should be admitted to a hospital whenever child abuse is suspected. From 9 to 11 percent of burns in children are nonaccidental injuries, with a peak incidence at 13 to 24 months of age.16 Immersion scalds are classic burn injuries in child abuse, but abuse should be suspected with any scald injury, especially if there is sharp demarcation between burned and normal skin or splash marks are absent.6 Child abuse should also be strongly suspected in children with burns suggestive of cigarette or hot-iron injuries.6

AMBULATORY TREATMENT

A systematic approach to the ambulatory management of burns is conceptualized by the six “Cs”: clothing, cooling, cleaning, chemoprophylaxis, covering and comforting (i.e., pain relief).4

Clothing. Any clothing that is hot or burned should be removed immediately from the patient's body. Clothing that has been exposed to chemicals should also be removed to avoid exposing the skin to continued burn insult. If clothing does not remove easily, nonadherent material should be cut away, with adherent clothing left for removal in the cleaning phase.

Cooling. Ideally, burns should be cooled immediately after they occur. Although most tissue has already cooled by the time patients with burns present to a physician, further cooling during the first several hours after injury effectively decreases burn pain.6 Sterile saline-soaked gauze, moderately cooled to around 12°C (53.6°F), can be applied to the burned tissues.17 Ice application should be avoided.6,18 Because of the risk of hyperthermia, caution should be exercised in cooling extensive burns (i.e., those with a TBSA of more than 10 percent).19

Cleaning. Cleaning a burn wound is critical but can cause excruciating pain. It is therefore important to establish local or regional anesthesia before the wound is cleaned. Anesthesia should not be applied topically to a burn or injected directly into the wound.6

Although disinfectants (e.g., chlorhexidine gluconate solution [Hibiclens], povidone-iodine solution [Betadine]) are often employed to clean burn wounds, their use is discouraged because these agents can actually inhibit the healing process.5 There is growing support for washing burns with mild soap and tap water.2,5,15,20,21 Once a burn wound has been cleaned, it should be thoroughly rinsed.

Tar and asphalt residues should never be debrided5; instead, they can be removed with a mixture of cool water and mineral oil.4 Applying copious amounts of polymyxin B–bacitracin zinc ointment (Polysporin) over several days should emulsify and remove residual tar.15 Embedded bits of clothing or other materials should be removed by copious irrigation using a large-gauge syringe.4

To minimize infection, necrotic tissue from partial- and full-thickness burns should be removed manually or with whirlpool debridement. The latter method tends to be better tolerated by patients. The yellow eschar characteristic of partial-thickness burns need not be removed.4

Ruptured blisters should be removed. Many experts recommend unroofing blisters if they contain cloudy fluid or are likely to rupture imminently (e.g., blisters located over joints).15,22 The management of clean, intact blisters is controversial. Intact blisters should never be aspirated with a needle because of the increased risk of infection.3,15,22 The persistence of blisters for several weeks, with no signs of resorption, typically indicates the presence of an underlying deep partial- or full-thickness burn.6

Chemoprophylaxis. Tetanus immunization should be updated in patients with wounds deeper than a superficial partial-thickness burn.23

Diagnosing infection in patients with burns is challenging. Burns elicit inflammation, which results in mild erythema, edema, pain and tenderness. If these signs occur in conjunction with lymphangitis, fever, malaise and anorexia, or if they increase over a baseline level, infection should be suspected.6

Infection can involve the depth and extent of a burn, converting a superficial partial-thickness burn into a deep partial-thickness burn or even a full-thickness burn. An infected burn is also more susceptible to blood invasion and sepsis. Because of these risks, all suspected burn infections warrant aggressive management, including hospital admission and parenteral antibiotic therapy.15 Some authors contend that all infected burns require surgical referral with consideration of full-thickness skin biopsy to confirm the presence of infection and identify the causative organism.4 Full-thickness skin grafting after excision should also be considered.24

Superficial burns do not require infection prophylaxis, but all other burns should receive topical prophylaxis. Classically, silver sulfadiazine cream (Silvadene) is used to prevent burn infections. This agent should never be used on the face or in patients with sulfonamide hypersensitivity. Because of the risk of sulfonamide kernicterus, silver sulfadiazine should not be used in pregnant women, newborns or nursing mothers with infants younger than two months of age.4

Bacitracin is an alternative topical prophylactic antibiotic. This agent should always be used around mucous membranes. Because of the decreased cost, several authors favor using bacitracin rather than silver sulfadiazine for any superficial partial-thickness burn.3 No studies comparing the efficacies of bacitracin and silver sulfadiazine have yet been published.

Alternatives to topical antibiotics include biologic dressings (pigskin, human allograft) and bismuth-impregnated petroleum gauze or Biobrane dressings. The advantage of these dressings is that they are applied only once. As a result, patients are spared the pain that typically accompanies dressing changes.

Biologic dressings are associated with lower infection rates and faster healing rates than silver sulfadiazine. However, these dressings are expensive, difficult to apply and not always readily available.14 If used, biologic dressings should be applied within the first six hours after the burn is sustained. The initial application may loosen by the following day, necessitating reapplication. Thereafter, these dressings gradually peel off as skin epithelializes underneath them. Early separation of the dressing from the skin indicates the presence of a deeper wound (requiring surgical treatment) or an infection.5

Bismuth-impregnated petroleum gauze and Biobrane dressings appear to be advantageous treatments and are acceptable for use in young children with superficial partial-thickness burns.14,25 Both of these dressings are applied as a single layer over the burn and are then covered with a bulky dressing. The bulky dressing should be changed every other day, typically in a physician's office, with close assessment of the wound for signs of infection.

Covering. Dogmatic recommendations regarding the type and duration of dressing cannot be made because of the paucity of studies on the subject.6 Covering burns serves a number of purposes. Dressings provide anesthetic relief, act as a barrier against infection and keep the wound dry by absorbing drainage. The types of coverings differ, depending on the depth of a burn and its location.

Superficial burns do not require wound dressings. Use of a simple skin lubricant (e.g., aloe vera cream) is sufficient, and patients should be instructed to see their physician if any blisters develop.

All partial- and full-thickness burns should be covered with sterile dressings. A fine mesh gauze (e.g., Telfa) should be applied after the burn has been cleaned and a thin layer of topical antibiotic has been applied. Circulatory impairment is minimized by applying this nonadherent dressing in successive strips, rather than wrapping it around the wound.16 The dressing is held in place with a tubular net bandage or lightly applied gauze wraps. Tubular net bandages come in a variety of sizes. This bandage is excellent for use on extremities, and it can be modified to fit the trunk of a younger child.

Recommended frequencies for dressing changes range from twice daily to once a week.6 Dressings should be changed whenever they become soaked with excessive exudate or other fluids.5 At each dressing change, the topical antibiotic should be removed as completely as possible using gentle washings. Scrubbing and sharp debridement are not necessary.5

Comforting. Analgesics should be given around the clock to control “background” pain. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (alone or in combination with opioids) are often appropriate for use in patients with small burn wounds.26 Aspirin products should be avoided because of platelet inhibition and the risk for bleeding.

A patient's worst pain score should be less than 5 (on a scale of zero to 10). Scores of 5 or higher interfere with sleep, activity and mood.28

Follow-Up Care for Burns

Follow-up care involves surveying patients with burns for signs of infection, scarring and contracture. To minimize further damage, infection is best managed in a hospital. Scarring and contractures connote long-term disfigurement and disability, both of which are indications for specialized care.

FOLLOW-UP INTERVALS

Patients with burns who are being managed as outpatients should be seen again on the day after injury. At this visit, the level of pain can be assessed, pain medication can be adjusted if necessary, and competence in managing dressing changes can be assessed. Subsequent follow-up can then be performed on a weekly basis until wound epithelialization occurs. However, if pain control is insufficient or there are concerns about the ability of a patient or family members to provide proper wound care, the patient should be seen on a daily basis until complete epithelialization occurs.2,6

If wound epithelialization has not begun after two weeks or if subsequent evaluations reveal the presence of a full-thickness burn more than 2 cm in diameter, the patient should be referred to a surgeon with expertise in burn care.2,6,15 Tiny opalescent islands of epithelium throughout the wound indicate epithelialization, with the wound typically healing completely in seven to 10 days.6

After epithelialization has occurred, patients are seen every four to six weeks to assess for evidence of hypertrophic scar formation and to monitor coping mechanisms.

HYPERTROPHIC SCARRING AND CONTRACTURES

It has been said that “time heals all wounds.” This is not necessarily the case with burns. Although the threat of infection and the magnitude of pain diminish with time, the prospects for long-term scarring and disability often become more apparent. Hypertrophic scarring is thought to be inevitable when epithelialization takes longer than two weeks in blacks and young children, or longer than three weeks in all other patients.29

Application of pressure to burn wounds is generally recommended to minimize hypertrophic scarring, although optimal pressure and duration have not yet been determined in controlled trials.30 A variety of techniques are used, but all are complex and costly. Therefore, family physicians often refer patients at risk for scarring to a burn specialist. Because pressure prevents scars but does not treat them once they develop, referral should be initiated promptly at the first sign of hypertrophic scarring or if a wound misses certain epithelialization milestones (Table 3).31

| Wound healing time | Early pressure treatment |

|---|---|

| > 10 days | Recommended for black patients |

| > 14 days | Recommended for patients of all ages and races |

| > 21 days | Mandatory for all patients |

Although pressure does little to remodel existing hypertrophic scars, the application of silicone gel sheeting has been found to significantly reduce established scars as late as 12 years after injury.31 A two-month trial of the continual use of silicon gel sheeting on established scars distinguishes responders from nonresponders.32 Side effects of pruritus and rash can be minimized by washing the scar and applying silicon gel daily.33

Scar contractures result in disfigurement and disability. If detected early, a contracture can be treated with silicone inserts and pressure. If the contracture is more developed, a continuously worn static splint is added to maintain sustained stretch. Once full range of motion is achieved, splinting can be reduced to nighttime use until the scar fully matures. Surgical intervention should be considered if the contracture is not completely reduced.31

ROLE OF SURGERY

Surgical excision and skin grafting beginning less than 72 hours after injury is beneficial and is indicated for nonscald full-thickness burns in children and in adults younger than 30 years of age.30,34 All other patients with suspected full-thickness burns should be observed for eight to 10 days, as nothing is lost by delaying surgical excision.5 It is also best to wait two weeks before assessing the need for surgery in children with hot-water scald burns because overly aggressive excision and skin grafting in this group has resulted in worse outcomes.35 Full-thickness burns less than 2 cm wide can be allowed to heal by contracture as long as they are in nonfunctional, noncosmetic areas and the skin is not thin (e.g., the ankle).21

COPING WITH THE INJURY

After epithelialization occurs, no further dressing changes are required. However, patients should be instructed to use a non-perfumed moisturizing cream (e.g., Vaseline Intensive Care, Eucerin, Nivea, mineral oil or cocoa butter)6 until natural lubricating mechanisms return.2 Use of preparations with a high lanolin content, thick waxes and ointments should be avoided.5 In addition, a sun block with a skin protection factor greater than 15 should be used to prevent hyperpigmentation until the wound loses its pink and red coloring.2 Depending on the depth of injury, it usually takes six months to two years for a burn wound to heal completely.5

Itching is a common problem during the healing process. Pruritus is often triggered or worsened by environmental extremes (especially heat), physical activity and stress.6 The itching usually diminishes gradually and eventually stops after complete wound healing.6 Until then, a number of measures can be employed to control itching. Systemic antihistamines are usually tried first, with diphenhydramine (Benadryl) used most frequently.5,6 Cyproheptadine (Periactin) and hydroxyzine (Atarax) are alternatives.6 Local measures include bicarbonate of soda baths and moisturizing lotions.5 Many patients prefer to wear loose, soft, cotton clothing.6

In addition to helping patients cope with long-term physical discomfort, family physicians should be alert for psychologic issues. Patients who have sustained burns are at increased risk for anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Family dynamics can also change dramatically. Family members may be stricken with guilt, and patients are susceptible to dependency issues because of the additional help required for daily activities while healing is occurring. If a psychologic issue is noticed, appropriate treatment should be implemented.27