A more recent article on cryptorchidism (undescended testicle) is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(9):2037-2044

See related patient information handout on the undescended testicle, written by the authors of this article.

Early diagnosis and management of the undescended testicle are needed to preserve fertility and improve early detection of testicular malignancy. Physical examination of the testicle can be difficult; consultation should be considered if a normal testis cannot be definitely identified. Observation is not recommended beyond one year of age because it delays treatment, lowers the rate of surgical success and probably impairs spermatogenesis. By six months of age, patients with undescended testicles should be evaluated by a pediatric urologist or other qualified subspecialist who can assist with diagnosis and treatment. Earlier referral may be warranted for bilateral nonpalpable testes in the newborn or for any child with both hypospadias and an undescended testis. Therapy for an undescended testicle should begin between six months and two years of age and may consist of hormone or surgical treatment. The success of either form of treatment depends on the position of the testicle at diagnosis. Recent improvements in surgical technique, including laparoscopic approaches to diagnosis and treatment, hold the promise of improved outcomes. While orchiopexy may not protect patients from developing testicular malignancy, the procedure allows for earlier detection through self-examination of the testicles.

Cryptorchidism, or undescended testicle, is usually diagnosed during the newborn examination. Recognition of the condition, identification of associated syndromes, proper diagnostic evaluation and timely referral for urologic surgical therapy are important steps in preventing adverse consequences.

Consequences of Cryptorchidism

The rationale for treatment of the undescended testicle is the prevention of potential sequelae. The most common problems associated with undescended testicles are testicular neoplasm, subfertility, testicular torsion and inguinal hernia.

TESTICULAR CANCER

It has been well documented that men with a history of undescended testicle have a higher-than-expected incidence of testicular germ cell cancers. While the likelihood of developing testicular cancer has probably been overestimated in the past, the incidence among men with an undescended testicle is approximately one in 1,000 to one in 2,500.1 Although significantly higher than the risk among the general population (1:100,000), this level of risk does not warrant radical therapy, such as removal of all intra-abdominal testes.

About 20 percent of testicular tumors in men with unilateral cryptorchidism occur on the side with the normally descended testicle2; this finding supports the argument against indiscriminate removal of undescended testes. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer may also be manifestations of a genetic testicular abnormality; therefore, the development of cancer in an undescended testis may not be caused by testicular malposition. Although there is no proof that orchiopexy reduces the risk of testicular cancer, it is performed to ease detection through testicular self-examination.3

SUBFERTILITY

As a group, men who have had an undescended testicle have lower sperm counts, poorer quality sperm and lower fertility rates than men whose testicles descended normally.4 The likelihood of subfertility increases with bilateral involvement and increasing age at the time of orchiopexy. Impaired spermatogenesis may be partially caused by underlying genetic abnormalities that can increase the risk of germ cell neoplasia. For this reason, impairment may not be completely reversible through surgical intervention.

Unlike the risk of testicular cancer, however, there seems to be an advantage to early orchiopexy for protection of fertility.5,6 Through testicular biopsy at the time of orchiopexy, germ cell density has been shown to decrease over time, beginning as early as one year of age.7,8 For this reason, treatment of the undescended testicle is recommended as early as six months of age and should be completed before age two.

TESTICULAR TORSION AND INGUINAL HERNIA

Although there is little solid evidence, the incidence of testicular torsion is thought to be higher in undescended testes than in normal scrotal testes.9 Torsion of an undescended testicle often occurs with the development of a testicular tumor,10 presumably caused by increased weight and distortion of the normal dimensions of the organ. Torsion of an intra-abdominal testicle may present as an acute abdomen. A nonpalpable testicle on physical examination should be a clue to the diagnosis, but often the torsion is only diagnosed at the time of abdominal exploration.

Most true cases of undescended testicles are associated with a patent processus vaginalis.11 If an overt hernia is present, expeditious hernia repair with orchiopexy at the age of presentation is undertaken. Otherwise, the hernia should be repaired at the time of orchiopexy. A man with an untreated, undescended testicle and an occult inguinal hernia may present at any time with symptoms and complications typical of any inguinal hernia.

Presentation and Anatomy

Most undescended testicles are present at birth. Up to one third of premature male newborns are born with an undescended testicle, and 3 to 5 percent of term male infants are affected.12 By three months of age, the incidence is reduced to 0.8 percent; between three months of age and adulthood, the incidence does not change.13 Watchful waiting is not an option because true undescended testicles rarely descend spontaneously after three months of age. A proposed algorithm for the management of newborns with cryptorchidism, including suggestions on when to refer patients to a pediatric urologist, is presented in Figure 1.

Occasionally, a testicle that is noted in early childhood to be in a scrotal position will “ascend” and become truly undescended. While physicians used to believe that this finding represented an error in physical examination, testicular ascent is now a well-documented phenomenon. It occurs in older children and young infants.14,15 In older children, testicular ascent probably represents an ectopic testicle with enough gubernacular laxity to reach the scrotum in early childhood. As the child grows, the ectopic gubernaculum tethers the testicle, which is pulled cephalad out of the scrotum.16 The mechanism of testicular ascent in the infant is not well established because this phenomenon is rarely reported.

Undescended testicles can be categorized on the basis of physical and operative findings: (1) true undescended testicles (including intra-abdominal, peeping at the internal ring and canalicular testes), which exist along the normal path of descent and have a normally inserted gubernaculum; (2) ectopic testicles, which have an abnormal gubernacular insertion; and (3) retractile testicles, which are not truly undescended. The most important category to distinguish on physical examination is the retractile testis, because no hormone or surgical therapy is required for this condition.

Approximately 20 percent of infants who present with cryptorchidism have at least one nonpalpable testicle. Through surgical examination, about one half of nonpalpable testes are found to be intra-abdominal, while the rest represent absent (vanishing) or atrophic testes.17,18 The vanishing testicle is thought to be caused by intrauterine testicular torsion.

Physical Examination

A general physical examination that emphasizes the signs of syndromic features may reveal an underlying reason for cryptorchidism, such as Prader-Willi, Kallmann's or Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndromes.19 The genitalia should be examined for evidence of hypospadias or ambiguity. Concurrence of hypospadias and undescended testis is commonly associated with states of intersexuality, especially mixed gonadal dysgenesis and true hermaphroditism.20

Testicular examination of the infant and young child requires a two-handed technique. One hand should start at the hip and gently sweep along the inguinal canal, aided by surgical lubricant or warm soapy water, if necessary (Figure 2, photo A). A true undescended or ectopic inguinal testicle will be felt to “pop” under the examiner's fingers during this maneuver (Figure 2, photos B and C). A low ectopic or retractile testicle will be felt by the opposite hand as it is “milked” into the scrotum (Figure 2, photo D). The ectopic testicle will immediately spring out of the scrotum when it is released. The retractile testicle will remain momentarily in the scrotum until further stimulation causes a cremasteric reflex.

Differentiation of a retractile testis from a true undescended testis is sometimes difficult; consultation with a urologist may be valuable. Position, consistency and size of the undescended testicle in relation to the opposite testis are noted. If a testis cannot be palpated in the inguinal canal or the scrotum, or in ectopic sites such as the femoral region or perineum, evaluation for a nonpalpable testis must be initiated. Sometimes tissue in the scrotum may feel like an atrophic testicle. Occasionally this tissue represents gubernaculum or dissociated epididymis and vas deferens,21 and may coexist with an intra-abdominal testis. Unless the presence of a testicle is clear, examination by a urologist is indicated.

Evaluation of the Bilateral Nonpalpable Testis

A phenotypically male newborn with bilateral nonpalpable testicles should be considered to be a genetic female with congenital adrenal hyperplasia until proved otherwise. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia may rarely present with a normal male phenotype and is a life-threatening condition. Ultrasound examination of the pelvic structures, karyotyping and measurements of serum electrolytes, testosterone, müllerian-inhibiting hormone, and adrenal hormones and metabolites (17–hydroxyprogesterone) should be considered in the initial evaluation. An older child with bilateral non-palpable testicles should be evaluated hormonally for testicular absence.22

Serum studies should include testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and müllerian-inhibiting substance (MIS). Elevations in LH and FSH, as well as the absence of detectable MIS, suggest testicular absence.23 Measurements of thyroid hormone and cortisol levels should be considered because hypogonadism may occur with pituitary aplasia. A stimulation test using intramuscular human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) can be administered to check for evidence of testosterone production. Definite hormonal evidence of testicular absence may preclude surgical exploration in the rare case of a newborn with bilateral absent testicles, but a minimum of both a negative hCG stimulation test and elevated gonadotropins must be included. Normal gonadotropin levels or detectable MIS levels warrant surgical exploration, even with a negative hCG stimulation test.

Except in certain circumstances, radiologic evaluation of the nonpalpable testicle is not warranted.24 None of the commonly applied studies, such as ultrasonography, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, is sensitive enough to detect the majority of intra-abdominal testes, and none is specific enough to exclude an intra-abdominal testis. Therefore, whether or not a testicle is located by the radiologic study, surgical exploration is required. Ultrasound examination may be advisable in the infant with bilateral nonpalpable testes to look for gonads and to exclude the presence of a uterus, which would suggest a state of intersexuality. Ultrasound examination may also be helpful in the overweight child to detect inguinal testicles that are difficult to palpate.

Therapy for the Undescended Testis

Treatment for cryptorchidism can be hormonal, surgical or a combination of the two. Because the process of testicular descent is hormonally mediated, it can sometimes be induced with hormone administration. Administration of systemic testosterone is minimally effective in achieving testicular descent because the process depends on a paracrine effect—high local levels of testosterone that cannot be achieved systemically.25 Using gonadotropins to stimulate the testicle to produce testosterone may help patients to achieve these high local levels.

In the United States, the only hormone labeled for the treatment of cryptorchidism is hCG, which is administered intramuscularly. There are many protocols for the use of hCG. One such protocol is the administration of 1,500 to 2,500 U two times per week for four weeks. Whatever protocol is used, the likelihood of success is greatest in the most distal true undescended testicles. In theory, an ectopic testis should not respond to hormone therapy because it is physically prevented from descending. A high undescended testis is unlikely to descend completely; if it does, it will probably ascend after the hormone stimulation is withdrawn.26 Some side effects of hCG administration can be disturbing for parents. These include enlargement of the penis, pubic hair growth, increased testicular size and aggressive behavior during administration.

Studies suggest that gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is more effective than hCG in achieving testicular descent.27 Unfortunately, the reported results of hormonal therapy in the United States and Europe vary widely, probably because of the inclusion of variable numbers of boys with retractile testes. At any rate, GnRH is not currently labeled for use in the treatment of cryptorchidism in the United States.

SURGERY FOR THE UNDESCENDED TESTIS

The inguinal orchiopexy is a well-established operation for the palpable undescended testicle.28 Postoperative management of the condition is fairly straightforward. To prevent dislodgment of the testis from the scrotum, the use of toys that must be straddled, such as bicycles, should be avoided for two weeks. Sports activities should also be limited in the older child.

Examination in the early postoperative period (one to two weeks after surgery) allows the physician to assess wound healing and remove any fixating sutures. Repeat examination should be performed at least three months after surgery to assess the position and size of the testicles.

The most significant complication of orchiopexy is testicular atrophy. Dissection of the testicular vessels and/or postoperative swelling and inflammation can result in ischemic injury and testicular atrophy. Although this is a rare complication of routine orchiopexy, a meta-analysis29 of the urologic literature suggested an 8 percent failure rate of orchiopexy, even in the distal undescended testis, and failure of more than 25 percent of orchiopexies for intra-abdominal testes. Other potential complications include ascent of the testis (which would require a second orchiopexy), infection and bleeding.

Orchiopexy should be performed by urologists who are well versed in the surgical procedure and the management of complications.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF THE NONPALPABLE TESTIS

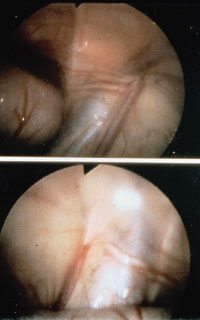

Surgery for the nonpalpable testicle is diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. Initially, it is important to determine whether a testis exists. If the absence of a testis is surgically confirmed by identifying blind-ending testicular vessels, the surgery should be terminated (Figure 3). Intra-abdominal blind-ending vessels are found in 9.8 percent of boys with nonpalpable testes.30 Sometimes the testicular vessels are traced to an abdominal, inguinal or scrotal testicular remnant, which is then removed. In about one half of cases, an intra-abdominal testis is found (Figures 4a through 4c), which is either brought to the scrotum or removed.

The two initial surgical approaches to the nonpalpable testis are the open inguinal and diagnostic laparoscopic techniques. In the open inguinal approach,31 the groin is explored. If cord structures or testicular remnants are found, they are removed, and the procedure is terminated. If the groin exploration is negative, the incision is extended, and the peritoneum is entered in a search for an intra-abdominal testis.

The second surgical approach to the nonpalpable testis is laparoscopic. Diagnostic laparoscopy, which is a safe procedure in experienced hands, is performed initially.32–34 Using a laparoscope placed through the umbilicus, the inguinal rings are examined, and the status of the processus vaginalis (patent or non-patent), wolffian structures and testicular vessels can be easily identified. The presence of blind-ending spermatic vessels confirms an absent testis, allowing termination of the procedure without a groin incision. If vessels and vas deferens exit the internal ring, the groin can be explored. If an intra-abdominal testis is identified, the physician can then choose the best surgical approach.