Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(3):559-567

Palpable thyroid nodules occur in 4 to 7 percent of the population, but nodules found incidentally on ultrasonography suggest a prevalence of 19 to 67 percent. The majority of thyroid nodules are asymptomatic. Because about 5 percent of all palpable nodules are found to be malignant, the main objective of evaluating thyroid nodules is to exclude malignancy. Laboratory evaluation, including a thyroid-stimulating hormone test, can help differentiate a thyrotoxic nodule from an euthyroid nodule. In euthyroid patients with a nodule, fine-needle aspiration should be performed, and radionuclide scanning should be reserved for patients with indeterminate cytology or thyrotoxicosis. Insufficient specimens from fine-needle aspiration decrease when ultrasound guidance is used. Surgery is the primary treatment for malignant lesions, and the extent of surgery depends on the extent and type of disease. Ablation by postoperative radioactive iodine is done for high-risk patients—identified as those with metastatic or residual disease. While suppressive therapy with thyroxine is frequently used postoperatively for malignant lesions, its use for management of benign solitary thyroid nodules remains controversial.

A thyroid nodule is a palpable swelling in a thyroid gland with an otherwise normal appearance. Thyroid nodules are common and may be caused by a variety of thyroid disorders. While most are benign, about 5 percent of all palpable nodules are malignant.1–4 Many tests and procedures are available for evaluating thyroid nodules, and appropriate selection of tests is important for accurate diagnosis. Family physicians should have a cost-effective method of differentiating between nodules that are malignant and those that will have a benign course. This article provides a method for the outpatient evaluation and treatment of thyroid nodules.

Epidemiology

Palpable thyroid nodules occur in 4 to 7 percent of the population (10 to 18 million persons), but nodules found incidentally on ultrasonography suggest a prevalence of 19 to 67 percent.1,5 In one study,6 30 percent of subjects 19 to 50 years of age had an incidental nodule on ultrasonography. In addition, more than one half of the thyroid glands studied contained one or more nodules, with only about one in 10 being palpable.6 Approximately 23 percent of solitary nodules are actually dominant nodules within a multinodular goiter.7 Thyroid carcinoma occurs in roughly 5 to 10 percent of palpable nodules.1 Of the estimated 1,268,000 cancers that were expected to be newly diagnosed in 2001 in the United States, 19,500 were expected to be of thyroid origin with 1,300 deaths attributable to thyroid cancer.8

Presentation

The majority of thyroid nodules are asymptomatic. Most persons with thyroid nodules are euthyroid, with less than 1 percent of nodules causing hyperthyroidism or thyrotoxicosis. Patients may complain of neck pressure or pain if spontaneous hemorrhage into the nodule has occurred. Questions about symptoms of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism are essential, as are questions about any nodule, goiter, family history of autoimmune thyroid disease (e.g., Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Graves' disease), thyroid carcinoma, or familial polyposis (Gardner's syndrome).

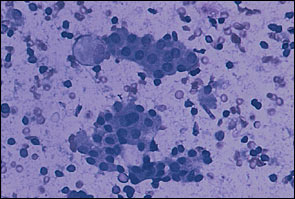

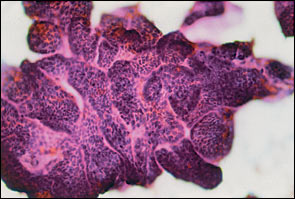

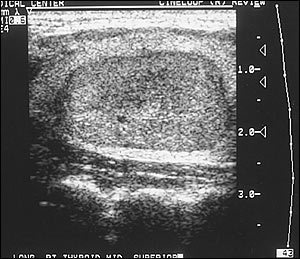

The various types of thyroid nodules are listed in Table 1. Colloid nodules are the most common and do not have an increased risk of malignancy. Most follicular adenomas are benign; however, some may share features of follicular carcinoma. About 5 percent of microfollicular adenomas prove to be follicular cancers with careful study.1 Thyroiditis also may present as a nodule (Figure 1). Thyroid carcinoma usually presents as a solitary palpable thyroid nodule. The most common type of malignant thyroid nodule is papillary carcinoma (Figure 2).

| Adenoma | Carcinoma | Colloid nodule | ||

| Macrofollicular adenoma (simple colloid) | Papillary (75 percent) | Dominant nodule in a multinodular goiter | ||

| Follicular (10 percent) | ||||

| Microfollicular adenoma (fetal) | Medullary (5 to 10 percent) | Other | ||

| Embryonal adenoma (trabecular) | Anaplastic (5 percent) | Inflammatory thyroid disorders | ||

| Hürthle cell adenoma (oxyphilic, oncocytic) | Other | Subacute thyroiditis | ||

| Thyroid lymphoma (5 percent) | Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis | |||

| Atypical adenoma | Cyst | Granulomatous disease | ||

| Adenoma with papillae | Simple cyst | Developmental abnormalities | ||

| Signet-ring adenoma | Cystic/solid tumors (hemorrhagic, necrotic) | Dermoid | ||

| Rare unilateral lobe agenesis | ||||

Physical Examination

Nodules are often discovered by the patient as a visible lump, or they are discovered incidentally during a physical examination. Thyroid nodules may be smooth or nodular, diffuse or localized, soft or hard, mobile or fixed, and painful or nontender. While palpation is the clinically relevant method of examining the thyroid gland, it can be insensitive and inaccurate depending on the skill of the examiner.6,9 Nodules that are less than 1 cm in diameter are not usually palpable unless they are located in the anterior portion of the thyroid lobe. Larger lesions are easier to palpate, except for those that lie deep within the gland. Regardless, about one half of all nodules detected by ultrasonography escape detection on clinical examination.9 In addition to palpation of the thyroid gland, a thorough examination of the lymph glands in the head and neck should be performed. Indicators of thyroid malignancy include the following: a hard, fixed lesion; lymphadenopathy in the cervical region; nodule greater than 4 cm; or hoarseness.

| Male gender |

| Extremes in age (younger than 20 years and older than 65 years) |

| Rapid growth of nodule |

| Symptoms of local invasion (dysphagia, neck pain, hoarseness) |

| History of radiation to the head or neck |

| Family history of thyroid cancer or polyposis (Gardner's syndrome) |

Diagnosis

In 1996, the Thyroid Nodule Task Force of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology created a practice guideline for patients with thyroid nodules.10 It was developed to formulate a clear, concise approach to the evaluation of thyroid nodules and “to increase the understanding of the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid nodules for physicians and patients.”10 Figure 311 is a diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of a thyroid nodule.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

A sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) test should be drawn on patients to determine those with thyrotoxicosis or hypothyroidism (Figure 4). When the TSH level is normal, aspiration should be considered. When this level is low, a diagnosis of hyperthyroidism should be considered; when the value is elevated, hypothyroidism is a possibility. Serum calcitonin should be measured in anyone with a family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid function tests should not be used to distinguish whether a thyroid nodule is benign or malignant.T4, antithyroid peroxidase antibodies, and thyroglobulin tests are not helpful in determining whether a thyroid nodule is benign or malignant, but they may be helpful in the diagnosis of Graves' disease or Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

FINE-NEEDLE ASPIRATION

In euthyroid patients with a nodule, a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) should be done first (Figure 5). According to guidelines from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, it is “believed to be the most effective method available for distinguishing between benign and malignant thyroid nodules,”10 with an accuracy approaching 95 percent,2 depending on the experience of the person performing the biopsy and the skill of the cytopathologist interpreting the slides. Analysis of the data suggests a false-negative rate of 1 to 11 percent, a false-positive rate of 1 to 8 percent, a sensitivity of 68 to 98 percent, and a specificity of 72 to 100 percent.2,10 Sampling errors occur in very large (more than 4 cm) and very small (less than 1 cm) nodules, and can be minimized by using ultrasound-guided biopsy. The results are interpreted as benign, malignant, suspicious, or indeterminate.

About 69 to 74 percent of specimens are found to be benign.2 Indeterminate or suspicious results occur in about 22 to 27 percent of all specimens.2 When specimens contain insufficient material for diagnosis, a repeat FNA should be performed. The incidence of insufficient results can be improved with the use of ultrasound-guided FNA. Finally, about 4 percent of specimens are positive for cancer and most false-positive results usually indicate Hashimoto's thyroiditis.2

RADIOLOGY

While ultrasonography is not yet the standard of care, recent studies12–15 support this practice once a nodule has been palpated to document size, location, and character of the nodule (Figure 6). Ultrasound-guided aspiration of nodules larger than 1 cm or smaller than 1 cm if solid and hypoechoic provides the highest cost-effective yield for detecting thyroid malignancy.12 While ultrasonography cannot distinguish benign from malignant nodules, it can be used to determine changes in size of nodules over time, either in the follow-up of a lesion thought to be benign or in detecting recurrent lesions in patients with thyroid cancer. The incidence of indeterminate specimens from FNA decreases from 15 percent to less than 4 percent when ultrasound guidance is used in conjunction with FNA.13 Frequently, thyroid nodules are found incidentally during ultrasonography of the neck for reasons not relating to the thyroid gland.

Nuclear imaging cannot reliably distinguish between benign and malignant nodules and is not required if nodules are present. FNA biopsy has replaced nuclear imaging as the initial evaluation procedure. However, in patients with a suppressed TSH level, a thyroid scan determines regional uptake or function and can be used as a secondary study.

The thyroid scan measures the amount of iodine trapped within the nodule. A normal scan indicates that the iodine (usually technetium 99m isotope) uptake is similar in both lobes of the thyroid gland. A nodule is classified as “cold” (decreased uptake), “warm” (uptake similar to that of surrounding tissue), or “hot”(increased uptake).4 While a large proportion of thyroid nodules may be cold on radionuclide scan, only 5 to 15 percent of these are malignant.3 Radioiodine scans also are useful in nodules with indeterminate cytology results, because a hyperfunctional nodule is almost always benign and can be managed medically with radioactive iodine or surgery.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has no place in the assessment of patients with thyroid nodules.10 Increasingly, however, thyroid nodules are being found incidentally during MRI of the neck for reasons not relating to the thyroid gland. The same is true for computed tomography.

Treatment

The main indications for surgical treatment of thyroid nodules are malignancy or indeterminate cytology on FNA, and suspicious history and physical examination. If the diagnosis of thyroid cancer is known preoperatively, many experts recommend partial or total thyroidectomy. However, this remains controversial, and debate about partial thyroidectomy continues.16 Ablation by postoperative radioactive iodine (I-131) is done for high-risk patients (i.e., those with metastatic disease, nodal disease, or gross residual disease). Postoperative thyroid replacement therapy is a common practice, although the benefits of administration remain controversial, especially in low-risk patients.9,16,17 Following complete resection of thyroid cancer, the TSH concentration should be in the target range of 0.5 μU per mL (0.5 mU per L). Greater suppression may be necessary for high-risk patients and those with a metastatic or locally invasive tumor that was not completely removed surgically or ablated by postoperative I-131 therapy.9,16,17

Nodules with indeterminate findings should be surgically removed,10 especially those found to be cold nodules on nuclear imaging. Hot functioning nodules may not require surgery, but if they are toxic nodules (suppression of sensitive TSH or symptoms such as atrial fibrillation), they will require treatment. Radioactive iodine may be the treatment of choice for patients with hot nodules, although some patients may choose surgery.

Most patients with benign biopsies can be followed without surgery and monitored carefully; however, some patients choose surgery after being fully informed of the risks. Patients who prefer surveillance should be monitored for changes in nodule size and symptoms, and repeat ultrasonography or FNA biopsy should be performed if the nodule grows. Repeated recurrence of cystic lesions is sufficient reason for surgical removal of the cyst.

Most incidental nodules found on routine testing with ultrasonography are benign and can be monitored with no further testing and follow-up observation. However, FNA biopsy is indicated if the nodule becomes palpable, has findings suggestive of malignancy on ultrasonography, or is larger than 1.5 cm, or if the patient has a history of head or neck irradiation (especially in childhood) or a strong family history of thyroid cancer.5

SUPPRESSION TREATMENT

Patients who benefit most from suppression therapy postoperatively are those who received radiation in childhood for benign conditions such as acne or an enlarged thymus. In this group, the recurrence rate of thyroid nodules after surgical removal is almost five times lower when thyroxine is given postoperatively than when it is not.18

Use of TSH suppressive therapy with thyroxine to manage benign, solitary thyroid nodules remains controversial. The lack of universal efficacy makes such therapy optional in most patients. Some randomized, controlled studies7,9 suggest that short-term thyroxine therapy is not superior to placebo in patients with a solitary hypofunctioning colloid nodule. The efficacy of thyroxine is less certain for solitary nodules than for a diffuse or multinodular goiter. However, some patients may benefit, and suppressive therapy is considered an appropriate alternative as long as the patient is followed carefully at six-month intervals.11,17

When thyroxine therapy is selected to manage a benign thyroid nodule, the medication should be prescribed in dosages sufficient to suppress the TSH level to 0.1 to 0.5 μU per mL (0.1 to 0.5 mU per L) for six to 12 months.11 More prolonged therapy should be reserved for patients in whom a decrease in nodule size is documented by ultrasonography. After 12 months, the dosage of thyroxine should be decreased to maintain the serum concentration of TSH in the low normal range. The patient and physician must weigh the benefits of long-term therapy and the potential risks. While this option could be considered in younger women, decreased bone density and cardiac side effects, such as atrial fibrillation, present a concern and potential risk in post-menopausal women.

THYROID NODULES IN CHILDREN AND DURING PREGNANCY

While the prevalence of thyroid nodules is less common in children, the risk of malignancy appears to be much higher (14 to 40 percent in children as opposed to 5 percent in adults).19 Recent reports suggest FNA biopsy has an important role in the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules in children.10,19,20 However, studies involving children have been limited, and false-negative results have raised concerns about the accuracy of this test in children.19

Thyroid nodules in pregnant women can be managed in the same way as in nonpregnant patients, except that radionuclide scanning is contraindicated.10 FNA biopsy can be performed during pregnancy, and surgical removal of thyroid nodules is relatively safe during the second trimester, which is the safest time for surgery during pregnancy. Surgery also can be deferred until after the pregnancy.