Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):93-102

Hair loss (alopecia) affects men and women of all ages and often significantly affects social and psychologic well-being. Although alopecia has several causes, a careful history, close attention to the appearance of the hair loss, and a few simple studies can quickly narrow the potential diagnoses. Androgenetic alopecia, one of the most common forms of hair loss, usually has a specific pattern of temporal-frontal loss in men and central thinning in women. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved topical minoxidil to treat men and women, with the addition of finasteride for men. Telogen effluvium is characterized by the loss of “handfuls” of hair, often following emotional or physical stressors. Alopecia areata, trichotillomania, traction alopecia, and tinea capitis have unique features on examination that aid in diagnosis. Treatment for these disorders and telogen effluvium focuses on resolution of the underlying cause.

Evaluating and treating hair loss (alopecia) is an important part of primary care, yet many physicians find it complex and confusing. Hair loss affects men and women of all ages and frequently has significant social and psychologic consequences. This article reviews the physiology of normal hair growth, common causes of hair loss, and treatments currently available for alopecia.

Normal Hair Growth

Each day the scalp hair grows approximately 0.35 mm (6 inches per year), while the scalp sheds approximately 100 hairs per day, and more with shampooing.1 Because each follicle passes independently through the three stages of growth, the normal process of hair loss usually is unnoticeable. At any one time, approximately 85 to 90 percent of scalp follicles are in the anagen phase of hair growth. Follicles remain in this phase for an average of three years (range, two to six years).1 The transitional, or catagen, phase of follicular regression follows, usually affecting 2 to 3 percent of hair follicles. Finally, the telogen phase occurs, during which 10 to 15 percent of hair follicles undergo a rest period for about three months. At the conclusion of this phase, the inactive or dead hair is ejected from the skin, leaving a solid, hard, white nodule at its proximal shaft.2 The cycle is then repeated.

Evaluation of Hair Loss

A directed history and physical examination usually uncover the etiology of hair loss. The history should focus on when the hair loss started; whether it was gradual or involved “handfuls” of hair; and if any physical, mental, or emotional stressors occurred within the previous three to six months3 (Table 1). Determining whether the patient is complaining of hair thinning (i.e., gradually more scalp appears) or hair shedding (i.e., large quantities of hair falling out) may clarify the etiology of the hair loss.4

| If the patient has or had… | Consider… | |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic/chronic illness (e.g., autoimmune disorder, cancer) | Alopecia areata, cicatricial alopecia, telogen effluvium | |

| Infection (systemic or local) | Cicatricial alopecia, telogen effluvium, tinea capitis | |

| Medication exposure (especially chemotherapy) or serious illness within previous three to four months | Telogen effluvium | |

| Psychiatric disorder (e.g., psychosis, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder) | Trichotillomania | |

| Physical stress (e.g., surgery, pregnancy, malnutrition) or life-threatening psychologic stress | Telogen effluvium | |

| Tight braids or “pulled-back” hairstyle | Traction alopecia | |

| Signs and symptoms of hormonal abnormalities | ||

| Hirsutism, amenorrhea, infertility | Androgenetic alopecia (women) | |

| Hypothyroidism, other endocrinopathies | Alopecia areata, telogen effluvium | |

The pattern of hair loss, especially whether it is focal or diffuse, also may be helpful (Figure 1). The hair-pull test gives a rough estimate of how much hair is being lost.2,4 It is done by grasping a small portion of hair and gently applying traction while sliding the fingers along the hair shafts. Usually one to two hairs are removed with this technique. The hairs are then examined under a microscope (Table 2).

| Hair loss disorder | Studies | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Female androgenetic alopecia | Prolactin, FSH, LH, DHEAS | Hyperandrogenism |

| Telogen effluvium | TSH, other endocrine tests | Metabolic disorder |

| Alopecia areata, telogen effluvium | ESR, ANA, RF | Autoimmune disease |

| Alopecia areata | CBC | Pernicious anemia |

| Tinea capitis | Culture swab, KOH examination, fluorescence with Wood's lamp* | Fungal infection |

| Telogen effluvium | Hair-pull test with microscopic evaluation | White bulb on shaft |

| Tinea capitis, environmental/external factor, systemic disease | Same as above | Mid-shaft, fractured hairs |

| Alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis | Same as above | Exclamation-point hairs |

| Telogen effluvium | Hair-pluck test | Increased telogen:anagen ratio |

| Unclear etiology, mixed signs/ symptoms, failure to improve with treatment | Scalp biopsy | Underlying pathology |

Androgenetic Alopecia

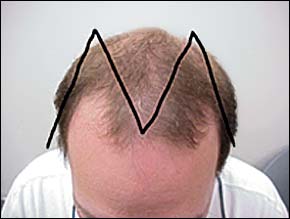

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA), or male-pattern baldness, is hair thinning in an “M”-shaped pattern; hair loss occurs on the temples and crown of the head with sparing of the sides and back5 (Figure 2). This pattern reflects the distribution of androgen-sensitive follicles in most people.6 Starting at puberty, androgens shorten the anagen phase and promote follicular miniaturization, leading to vellus-like hair formation and gradual hair thinning.6

Women also may experience AGA, often with thinning in the central and frontal scalp area but usually without frontal–temporal recession (Figure 3). A history and physical examination aimed at detecting conditions of hyperandrogenism, such as hirsutism, ovarian abnormalities, menstrual irregularities, acne, and infertility are indicated. Laboratory tests are of little value in women with AGA who do not have characteristics of hyperandrogenism.5

Treatment options for AGA (Table 3)6 focus on decreasing androgen activity. Minoxidil (Rogaine) and finasteride (Propecia) are the only medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AGA (Figure 4).6 Minoxidil is available without a prescription as a 2-percent topical solution that can be used by both men and women and as a 5-percent solution (Rogaine Extra Strength) that should be used by men only. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil promotes hair growth is unknown, but it appears to act at the level of the hair follicle. Minoxidil is an effective treatment for male and female AGA and is recommended as first-line treatment by the American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.5

Minoxidil should be applied twice daily, and one year of use is recommended before assessing its efficacy.6,7 Women also may benefit from adjunctive treatments such as estrogen (hormone replacement or oral contraceptives) or spironolactone (Aldactone). In men, minoxidil may work better in areas with higher concentrations of miniaturized hairs, and its efficacy may be increased by the synergistic use of once-daily tretinoin (Retin-A) applied at separate times during the day.6,8 Minoxidil does not work on completely bald areas and has relatively few side effects; a dosage of 2 mL per day of a 2-percent solution costs about $10.00 to $12.50 per month.

Finasteride inhibits 5α-reductase type 2, resulting in a significant decrease in dihydrotestosterone (DHT) levels.6 Studies have shown that, compared with placebo, 1 mg per day of finasteride slows hair loss and increases hair growth in men.6,7,9 Dosages as low as 0.2 mg per day result in decreased scalp and serum DHT levels in men, although the DHT levels may not correlate clinically with changes in hair loss.10

Finasteride has relatively few side effects, and a dosage of 1 mg per day costs about $49.50 per month. Women who could be pregnant should not handle finasteride, because it may cause birth defects in a male fetus. Finasteride has not proved effective in the treatment of female AGA and is not FDA-approved for use in women.11 [Evidence level A: randomized controlled trial] Continued use is required to maintain benefits.

Spironolactone, an aldosterone antagonist with antiandrogenic effects, works well as a treatment for hirsutism and may slow hair loss in women with AGA, but it does not stimulate hair regrowth. Estrogen may help to maintain hair status in women with AGA, but it also does not help with regrowth. Few controlled studies have examined the many non–FDA-approved hair growth agents such as cyproterone acetate (not available in the United States), progesterone, cimetidine (Tagamet), and multiple non-prescription and herbal products. A full discussion of approved and unapproved treatments for AGA can be found elsewhere.6,7 In all forms of alopecia, hairpieces and surgical transplants can produce satisfactory results but are expensive.

Telogen Effluvium

Telogen effluvium occurs when the normal balance of hairs in growth and rest phases is disrupted, and the telogen phase predominates. The disproportionate shedding leads to a decrease in the total number of hairs. Axillary and pubic areas often are involved, as well as the scalp.2 The hair-pluck test usually shows that up to 50 percent of hairs are in the telogen phase (in contrast to the normal 10 to 15 percent), although these results can vary in persons with advanced disease.4 The patient often is found to have had inciting events in the three to four months before the hair loss (Table 4).1,4 If 70 to 80 percent of hairs are in the telogen phase, the physician should look for causes of severe metabolic derangements, toxic exposures, or chemotherapy.1,4 No specific treatment for hair loss is required because normal hair regrowth usually occurs with time and resolution of underlying causes. Lack of significant historical events and a delay in regrowth should raise suspicion for syphilitic alopecia.1

Alopecia Areata

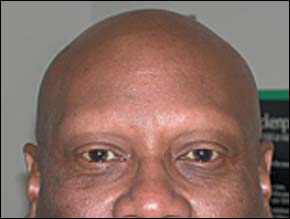

Alopecia areata is characterized by a localized area of complete hair loss (Figure 5). This may extend to the entire scalp (alopecia totalis) or the entire body (alopecia universalis)12,13 (Figure 6). Alopecia areata is probably secondary to an autoimmune reaction involving antibody, T-cell, and cytokine-mediated losses.14–16 The trait appears to be polygenic, affecting 0.1 to 0.2 percent of the population, with men and women equally affected.14 On microscopic evaluation, “exclamation-point” hairs are found, in which the proximal hair shaft has thinned but the distal portion remains of normal caliber (Figure 7). Spontaneous recovery usually occurs within six to 12 months, with hair in areas of re-growth often being pigmented differently.1,13 Prognosis is not as good if the condition persists longer than one year, worsens, or begins before puberty. Persons with a family history of the disorder, atopy, or Down syndrome also have a poorer prognosis.1 The recurrence rate is 30 percent, and recurrence usually affects the initial area of involvement.12 Thyroid abnormalities, vitiligo, and pernicious anemia frequently accompany alopecia areata.1,12,14

In addition to diagnosing and treating any underlying disorder, treatments for alopecia areata include immunomodulating agents and biologic response modifiers (Table 5).6 Although topical and oral corticosteroids have been used, the treatment of choice in patients older than 10 years with patchy alopecia areata affecting less than 50 percent of the scalp is intralesional corticosteroid injections (Figure 8).6

| Immunomodulators | |

| Corticosteroids | |

| Anthralin (Anthra-Derm) | |

| PUVA | |

| Contact sensitizers (experimental) | |

| Dinitrochlorobenzene | |

| Squaric acid dibutyl ester | |

| Diphenylcyclopropenone | |

| Biologic response modifiers | |

| Minoxidil (Rogaine) | |

Triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog), 0.1 mL diluted in sterile saline to 10 mg per mL, is injected intradermally at multiple sites within the area to a maximum dosage of 2 mL per visit.6 The main side effect, atrophy, can be minimized by not injecting too superficially and by limiting the volume per site and the frequency of injection (no more often than every four to six weeks).6 Because spontaneous resolution often occurs in patients with alopecia areata, assessing treatment response can be difficult. Intralesional steroids should be discontinued after six months if no improvement has been noted.

Topical immunotherapy (i.e., contact sensitizers) is the most effective treatment option for chronic severe alopecia areata (Table 5).6 Response ranges from 40 to 60 percent for severe alopecia areata, and reaches approximately 25 percent for alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis.6 Because of potentially severe side effects, only clinicians who have experience with these agents should prescribe them.

Many other agents have been used to treat alopecia areata, including minoxidil, psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), and anthralin (Anthra-Derm), but success rates vary. Anthralin, an anti-psoriatic, in combination with topical corticosteroids and/or minoxidil, is a good choice for use in children and those with extensive disease because it is relatively easy to use and clinical irritation may not be required for efficacy.6 Hairpieces and transplants may be the only options available for persons with severe disease that remains unresponsive to available medical treatments. Patients with recalcitrant, recurrent, or severe disease should be referred to a subspecialist.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is a psychiatric impulse-control disorder.17 The mean age of onset is eight years in boys and 12 years in girls, and it is the most common cause of childhood alopecia.1,15 Although any part of the body can be involved, the scalp is the most common. Patients also may eat the plucked hairs (trichophagy), causing internal complications such as bowel obstruction.18 The hair loss often follows a bizarre pattern with incomplete areas of clearing (Figure 9). The scalp may appear normal or have areas of erythema and pustule formation. A scalp biopsy may be necessary to rule out other etiologies, because patients may not acknowledge the habit.

Because of its psychologic nature, the mainstays of treatment are counseling, behavior modification techniques, and hypnosis. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other medications for depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder may be used in some cases, although no medications are FDA-approved for treatment of trichotillomania.17 If a more moth-eaten appearance of hair loss is present and no evidence of hair-pulling behavior can be elicited, syphilis should be suspected.

Traction Alopecia

In contrast to trichotillomania, traction alopecia involves unintentional hair loss secondary to grooming styles. It often occurs in persons who wear tight braids (especially “cornrows”) that lead to high tension and breakage in the outermost hairs (Figure 10). Traction alopecia also occurs commonly in female athletes who pull their hair tightly in ponytails. The hair loss usually occurs in the frontal and temporal areas but depends on the hairstyle used. Treatment involves a change in styling techniques. Other hair-growth promoters may be needed in end-stage disease, in which the hair loss can be permanent even if further trauma is avoided.1

Tinea Capitis

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp, usually caused by Microsporum or Trichophyton species of dermatophytes19 (Figure 11). It usually occurs in prepubertal patients. The most severe form of tinea capitis is a kerion, a fluctuant, boggy lesion with overlying hair loss. Tinea capitis can result in widespread hair loss with increased fragility of the hairs and frequent breakage. If fungal infection is suspected, a potassium hydrochloride slide or culture can be obtained. A Wood's lamp fluoresces several types of fungi; however, the most common fungus in the United States (i.e., Trichophyton tonsurans) does not fluoresce, lessening the value of this test. Treatment includes oral antifungal agents such as griseofulvin (Grifulvin), itraconazole (Sporanox), terbinafine (Lamisil), and fluconazole (Diflucan), with the newer agents having fewer side effects.20 Oral steroids may be necessary if a patient has a kerion, to decrease inflammation and potential scarring.

Cicatricial Alopecia

Cicatricial alopecias tend to cause permanent hair loss. These disorders destroy hair follicles without regrowth and follow an irreversible course.21 It is likely that they involve stem-cell failure at the base of the follicles, which inhibits follicular recovery from the telogen phase.21 Inflammatory processes, including repetitive trauma as in trichotillomania, also may lead to stem-cell failure. Other processes may be caused by autoimmune, neoplastic, developmental, and hereditary disorders. Among these are discoid lupus, pseudopelade in whites, and follicular degeneration syndrome in blacks. Dissecting cellulitis, lichen planopilaris, and folliculitis decalvans also may cause scarring alopecia. Some disorders respond to treatment with intralesional steroids or antimalarial agents.21 Patients with these conditions should be referred to a physician who specializes in hair loss disorders.