Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(2):235

Federally funded health centers and the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) depend on family physicians (FPs) and general practitioners (GPs) to meet the needs of millions of medically underserved people. Policy makers and workforce planners should consider how changes in the production of FPs would affect these programs.

For 40 years, the national network of community, migrant, rural, and homeless health centers has been delivering high-quality, cost-effective primary and preventive health care to low-income and otherwise medically underserved communities.1 They serve more than 3,600 communities in every U.S. state and territory. In 2003, federally funded health centers provided nearly 50 million visits for more than 12 million people who would otherwise have had great difficulty accessing care. Primary care physicians composed 95 percent of the physician staffing; more than one half were FPs or GPs.2

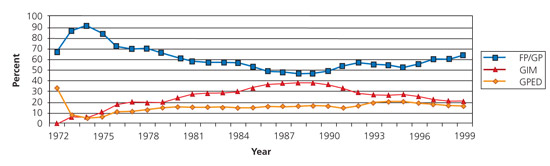

The NHSC addresses extreme physician distribution problems by placing physicians in locations that have difficulty attracting health care resources, and from 1971 through 1999 placed more than 18,000 health care professionals. Since the NHSC’s inception, FPs and GPs have dominated the physician workforce, contributing nearly 16,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs; i.e., one physician giving the equivalent of one full-time year of service), and making up 55 percent of the total FTEs (see accompanying figure).3 In 1999, FPs and GPs composed 78 percent of the NHSC primary care physician FTEs, and nearly 70 percent of non-federal physicians, in whole-county Health Professional Shortage Areas.4

These health care safety net programs depend on FPs to provide medical homes to millions of underserved people. Workforce planning must consider how changes in the production and training of FPs would affect them.