Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(5):827-830

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force Medical Service, the U.S. Air Force at large, the National Human Genome Research Institute, or the National Institutes of Health

To complement the 2005 Annual Clinical Focus on medical genomics, AFP is publishing a series of short reviews on genetic syndromes. This series was designed to increase awareness of these diseases so that family physicians can recognize and diagnose children with these disorders and understand the type of care they might require in the future. This review discusses Prader-Willi syndrome.

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), a genetic disorder that usually involves chromosome 15, is the most common form of obesity caused by a genetic syndrome. Diagnosis often is delayed until early childhood because the clinical findings are relatively nonspecific, particularly in infancy, and the dysmorphism often is subtle.1,2

Epidemiology

PWS is identified in approximately one in 25,000 births.3 Because many affected persons are not diagnosed at an early age, this statistic is likely an underestimate. More realistic estimates of PWS prevalence range from one in 10,000 to one in 15,000. PWS affects both sexes equally and occurs in persons of any race.

Clinical Presentation

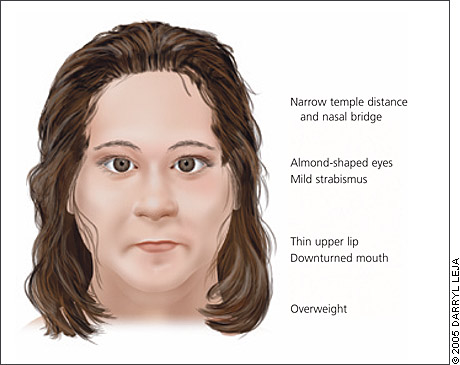

Typical findings on physical examination of persons with PWS are shown in Figures 1 and 2 and summarized in Table 14. Although PWS is associated with obesity, affected children classically present with difficulty feeding and subsequent failure to thrive in the first year of life. Newborns with PWS exhibit nonspecific findings including hypotonia, poor sucking reflex, diminished or absent cry, and somnolence. Early developmental milestones are delayed. After one year of age, there is a transition to hyperphagia. By school age, food-seeking behavior becomes increasingly difficult to control.

| Major criteria |

| Characteristic facial features (may include almond-shaped eyes, down-turned mouth, narrow bifrontal diameter, strabismus, thin upper lip; see Figures 1 and 2) |

| Developmental delay |

| Feeding problems/failure to thrive during infancy |

| Hypogonadism (may include cryptorchidism, hypoplastic scrotum, and small testes in males; hypoplastic labia minora and clitoris in females; and pubertal deficiency) |

| Infantile central hypotonia |

| Rapid weight gain between 1 and 6 years of age |

| Minor criteria |

| Decreased fetal movement and infantile lethargy |

| Esotropia, myopia |

| Hypopigmentation |

| Narrow hands with straight ulnar border |

| Short stature (compared with family members) |

| Skin picking |

| Sleep disturbance/sleep apnea |

| Small hands and feet |

| Speech articulation defects |

| Thick, viscous saliva |

| Typical behavioral problems |

Hypothalamic dysfunction is thought to be the basis for many of the phenotypic features, such as short stature and hypogonadism. Hypogonadism presents as cryptorchidism, small testes, and decreased scrotal rugae in males and small labia minora and clitoris in females. Puberty typically is delayed or incomplete.5

Learning disabilities always are present; however, affected persons may have low-normal intelligence to moderate mental retardation. Behavioral features in childhood include temper tantrums, high pain threshold, sleep disturbances, and skin picking.

Diagnosis

Although there are published consensus clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PWS, genetic testing has become the standard because it detects nearly 100 percent of persons with PWS, is highly specific, and can diagnose PWS earlier than would be possible based on clinical criteria.4,6 Clinical suspicion alone, even if based on relatively nonspecific findings, should prompt laboratory-based testing.

If an infant is hypotonic and has difficulty feeding, or if a child with this history in infancy has excessive food-seeking behavior, obesity, and global developmental delay, a high-resolution karyotype should be ordered, followed by methylation studies specific for PWS.6 Methylation analysis will identify virtually all persons affected with PWS. Many genetics laboratories offer both of these tests and can coordinate sequential testing. GeneTests, a publicly funded Web-based resource (http://www.genetests.org), provides an up-to-date laboratory directory with ordering information.

Genetics of PWS

With the exception of genes that are present on only one of the sex chromosomes, there are two copies of every gene—one inherited from a person’s mother and the other from the father. For some genes, only one copy from a chromosome pair is active or expressed. The specific gene that is expressed from a pair is determined by the sex of the parent transmitting it, a process called imprinting. The genes associated with PWS normally are expressed only from a region of chromosome 15 inherited from the father (PWS critical region, Figure 3). The genes inherited from the mother normally are inactivated. Therefore, children affected with PWS have a deletion or disruption of the chromosome inherited from the father or have inherited two copies of this chromosomal region from the mother. The latter situation is called maternal uniparental disomy.

Genetic counseling often is helpful for parents of a child affected with PWS who are contemplating another pregnancy. The risk of recurrence varies widely (zero to 50 percent) depending on the underlying genetic origin and can be determined based on the results of genetic testing. Other family members may be at risk for having a child with PWS and may benefit from genetic counseling.

Management

Treatment of a child affected with PWS involves the primary care physician and a multispecialty team that includes an ophthalmologist to evaluate for myopia and strabismus, a pediatric endocrinologist for consideration of growth hormone treatment, and a developmental pediatrician. Infants may require supplemental tube feedings to avoid failure to thrive. Physicians should be vigilant for hypoventilation and subsequent pulmonary infections secondary to hypotonia, because these conditions may cause early death.7 Early intervention for motor skills, speech, and language is necessary, as is an individualized education plan at the start of school. Generally, after the first year of life, strict dietary supervision and physical activity plans should be initiated to reduce complications of obesity.

Resources

Additional information about the diagnosis and management of PWS has been published8 and is available from the Prader-Willi Syndrome Association (U.S.A.) (http://www.pwsausa.org) and GeneTests (http://www.genetests.org).

Genomics Glossary

Expression: Process of converting DNA into protein.

Hyperphagia: Pathologically excessive appetite or eating.

Hypoplasia: Incomplete development of a tissue or organ.

Imprinting: Differential expression of a gene dependent on the sex of the parent of origin. For example, for a maternally imprinted gene there is no expression in the offspring; expression of the gene occurs from only the paternally inherited chromosome.

Methylation: (Attachment of methyl groups (−CH3) to cytosine (C) bases. Methylation can regulate)the transcription of genes (e.g., reducing the amount of protein generated). Hypermethylation can lead to silencing of a gene and total absence of protein production.

Uniparental disomy: Abnormal presence of both copies of a chromosome (or part of a chromosome) inherited from one parent.