Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(9):1558-1568

A more recent article on high blood pressure in children and adolescents is available.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

The development of a national database on normative blood pressure levels throughout childhood has contributed to the recognition of elevated blood pressure in children and adolescents. The epidemic of childhood obesity, the risk of developing left ventricular hypertrophy, and evidence of the early development of atherosclerosis in children would make the detection of and intervention in childhood hypertension important to reduce long-term health risks; however, supporting data are lacking. Secondary hypertension is more common in preadolescent children, with most cases caused by renal disease. Primary or essential hypertension is more common in adolescents and has multiple risk factors, including obesity and a family history of hypertension. Evaluation involves a thorough history and physical examination, laboratory tests, and specialized studies. Management is multifaceted. Nonpharmacologic treatments include weight reduction, exercise, and dietary modifications. Recommendations for pharmacologic treatment are based on symptomatic hypertension, evidence of endorgan damage, stage 2 hypertension, stage 1 hypertension unresponsive to lifestyle modifications, and hypertension with diabetes mellitus.

The prevalence and rate of diagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents appear to be increasing.1 This is due in part to the increasing prevalence of childhood obesity as well as growing awareness of this disease. There is evidence that childhood hypertension can lead to adult hypertension.2 Hypertension is a known risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) in adults, and the presence of childhood hypertension may contribute to the early development of CAD. Reports show that early development of atherosclerosis does exist in children and young adults and may be associated with childhood hypertension.3

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is the most prominent clinical evidence of end-organ damage in childhood hypertension. Data show that LVH can be seen in as many as 41 percent of patients with childhood hypertension.4–6 Patients with severe cases of childhood hypertension are also at increased risk of developing hypertensive encephalopathy, seizures, cerebrovascular accidents, and congestive heart failure. Based on these observations, early detection of and intervention in children with hypertension are potentially beneficial in preventing long-term complications of hypertension.

Data associating childhood hypertension with cardiovascular risk in adulthood are lacking. An update of recommendations for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of childhood hypertension is provided in the fourth report by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program (NHBPEP) Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents.7

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure should be checked routinely at every visit in children three years of age and older. | C | 7 |

| Three separate readings of an elevated blood pressure (greater than 90th percentile for age, height, and sex) on separate visits are needed to make the diagnosis of hypertension. | C | 7 |

| Patients diagnosed with primary hypertension should have a comprehensive assessment for cardiovascular risk factors (lipid profile, fasting glucose, body mass index). | C | 7 |

| Nonpharmacologic treatment (e.g., weight loss, dietary modifications, exercise) should be first-line therapy in patients with stage 1 hypertension. | C | 7 |

| Pharmacologic treatment should be initiated in patients with stage 2 hypertension, symptomatic hypertension, when end-organ damage is present (left ventricular hypertrophy, retinopathy, proteinuria); and in stage 1 hypertension when blood pressure is unresponsive to lifestyle changes. | C | 7 |

Epidemiology

Because body size is an essential determinant of blood pressure in children, it is necessary to include the child's height percentile to determine if blood pressure is normal. The revised childhood blood pressure tables include 50th, 90th, 95th, and 99th percentiles by sex, age, and height based on the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data (Appendices 1 and 2).7

Reports have shown an association between blood pressure and body mass index (BMI),8,9 suggesting that obesity is a strong risk factor for developing childhood hypertension. There are insufficient data that define the role of race and ethnicity in childhood hypertension, although results of several studies10–13 show black children having higher blood pressure than white children. Heritability of childhood hypertension is estimated at 50 percent.14 One report15 noted that 49 percent of patients with primary childhood hypertension had a relative with primary hypertension, and that 46 percent of patients with secondary childhood hypertension had a relative with secondary hypertension. Another report16 showed that in adolescents with primary hypertension there is an overall 86 percent positive family history of hypertension. There is evidence that shows breastfeeding in infancy may be associated with a lower blood pressure in childhood.17–19

Blood Pressure Measurement

According to the NHBPEP recommendations, children three years of age or older should have their blood pressure measured when seen at a medical facility7; however, according to the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF), there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for childhood hypertension to reduce the risk of CAD.20

The preferred method for blood pressure measurement is auscultation. Aneroid manometers are used to measure blood pressure in children and are accurate when calibrated on a semiannual basis.21

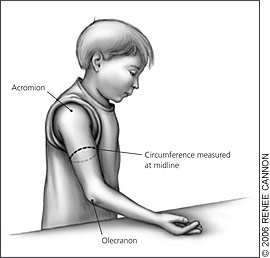

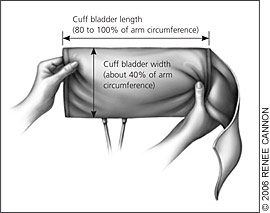

Correct measurement of blood pressure in children requires use of a cuff that is appropriate to the size of the child's upper right arm. This is the preferred arm because of the possibility of decreased pressures in the left arm caused by coarctation of the aorta. By convention, an appropriate cuff size is one with an inflatable bladder width that is at least 40 percent of the arm circumference at a point midway between the olecranon and the acromion (Figure 1). The cuff bladder length should cover 80 to 100 percent of the circumference of the arm7 (Figure 2). An oversized cuff can underestimate the blood pressure, whereas an undersized cuff can overestimate the measurement. Blood pressure should be measured in a controlled environment after five minutes of rest in the seated position with the right arm supported at heart level. If the blood pressure is greater than the 90th percentile, the blood pressure should be repeated twice at the same office visit to test the validity of the reading.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) requires a patient to wear a portable monitor that records blood pressure over a specified period. This allows measurements outside of the medical setting, where some patients may experience elevated blood pressure caused by anxiety (“white-coat hypertension”). Other uses for ABPM include episodic hypertension, autonomic dysfunction, and chronic kidney disease. ABPM also may have a role in differentiating primary from secondary hypertension and in identifying patients likely to have hypertension-induced end-organ damage.22 The USPSTF maintains that ABPM is subject to many of the same errors seen in the physician's office.20

Etiologies

Most childhood hypertension, particularly in preadolescents, is secondary to an underlying disorder (Table 27). Renal parenchymal disease is the most common (60 to 70 percent) cause of hypertension.23 Adolescents usually have primary or essential hypertension, making up 85 to 95 percent of cases.23 Table 323–25 shows causes of childhood hypertension according to age.

| Physical examination finding | Possible etiologies |

|---|---|

| Abdominal bruit | Renal artery stenosis |

| Abdominal mass | Polycystic kidney disease; hydronephrosis/obstructive renal lesions; neuroblastoma; Wilms' tumor |

| Acne | Cushing's syndrome |

| Adenotonsillar hypertrophy | Sleep disorder associated with hypertension |

| Decreased perfusion of lower extremities | Coarctation of the aorta |

| Diaphoresis | Pheochromocytoma |

| Flushing | Pheochromocytoma |

| Growth retardation | Chronic renal failure |

| Hirsutism | Cushing's syndrome |

| Joint swelling | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Malar rash | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Moon facies | Cushing's syndrome |

| Murmur | Coarctation of the aorta |

| Muscle weakness | Hyperaldosteronism |

| Obesity (general) | Association with primary hypertension |

| Obesity (of the face, neck, or trunk) | Cushing's syndrome |

| Tachycardia | Hyperthyroidism; pheochromocytoma; neuroblastoma |

| Thyromegaly | Hyperthyroidism |

| Age | Causes |

|---|---|

| One to six years | Renal parenchymal disease; renal vascular disease; endocrine causes; coarctation of the aorta; essential hypertension |

| Six to 12 years | Renal parenchymal disease; essential hypertension; renal vascular disease; endocrine causes; coarctation of the aorta; iatrogenic illness |

| 12 to 18 years | Essential hypertension; iatrogenic illness; renal parenchymal disease; renal vascular disease; endocrine causes; coarctation of the aorta |

Essential hypertension rarely is found in children younger than 10 years and is a diagnosis of exclusion. Significant risk factors for essential hypertension include family history and increasing BMI. Some sleep disorders and black race can be potential risk factors for essential hypertension. Essential hypertension often is linked to other risk factors that make up metabolic syndrome and can lead to cardiovascular disease. These risk factors for metabolic syndrome include low plasma high-density lipoprotein, elevated plasma triglycerides, abdominal obesity, and insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adolescents is between 4.2 and 8.4 percent.26

Secondary hypertension is more common in children than in adults. It can present in adolescents, especially if they have physical findings not typically seen with essential hypertension. Renal disease is the most common cause of secondary hypertension in children.23–25 Other causes include endocrine disease (e.g., pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism) and pharmaceuticals (e.g., oral contraceptives, sympathomimetics, some over-the-counter preparations, dietary supplements). Transient rise in blood pressure, which can be mistaken for hypertension, is seen with caffeine use and certain psychological disorders (e.g., anxiety, stress).

Evaluation

Once hypertension has been confirmed, an extensive history and careful physical examination should be conducted to identify underlying causes of the elevated blood pressure and to detect any end-organ damage. With the appropriate information, unnecessary and often expensive laboratory and imaging studies can be avoided. The NHBPEP has developed an algorithm to help the physician navigate the diagnostic and management choices in childhood hypertension (Figure 3).7

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

As mentioned previously, the child with primary hypertension often has a positive family history of hypertension or cardiovascular disease. Other risk factors including metabolic syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing (from snoring to obstructive sleep apnea) also are associated with primary hypertension. A careful history will uncover these important elements. It is helpful to remember that secondary hypertension is more likely in a younger child with stage 2 hypertension, thus data about systemic conditions associated with elevated blood pressure should be elicited. Because most secondary hypertension is renovascular in origin, a focused review of that system may provide insight into the possible etiology. Table 47 is a summary of information in a patient's history that can help determine the causes of childhood hypertension. A medication history should include any use of over-the-counter, prescription, and illicit drugs because many medications and drugs can elevate blood pressure. The physician should also ask about the use of performance-enhancing substances, herbal supplements (e.g., ma huang), and tobacco use.

| Possible etiology and/or associations | |

|---|---|

| Family history | |

| Cardiovascular disease (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke) | Primary hypertension |

| Deafness | Congenital or familial renal disease |

| Dyslipidemia | Primary hypertension |

| Endocrine problems (e.g., diabetes, thyroid, adrenal) | Familial endocrinopathies |

| Hypertension | Primary hypertension |

| Kidney disease | Congenital or familial renal disease |

| Sleep apnea | Primary hypertension |

| Child's history | |

| Chest pain | Cardiovascular disease |

| Diaphoresis (abnormal) | Endocrinopathies |

| Dyspnea on exertion | Cardiovascular disease |

| Edema | Cardiovascular disease |

| Enuresis | Renovascular disease, renal scarring |

| Growth failure | Endocrinopathies |

| Heat or cold intolerance | Endocrinopathies |

| Heart palpitations | Cardiovascular disease |

| Headaches | Primary hypertension |

| Hematuria | Renovascular disease, renal scarring |

| Joint pain or swelling | Rheumatologic disorders |

| Myalgias | Rheumatologic disorders |

| Neonatal hypovolemia/shock | Renovascular disease, renal scarring |

| Recurrent rashes | Rheumatologic disorders |

| Snoring or other sleep problems | Primary hypertension |

| Umbilical artery catheterization | Renovascular disease, renal scarring |

| Urinary tract infections (recurrent) | Renovascular disease, renal scarring |

| Weight or appetite changes | Endocrinopathies |

Physical examination should include calculation of BMI because of the strong association between obesity and hypertension. Obtaining blood pressure readings in the upper and lower extremities to rule out coarctation of the aorta also is recommended. Examination of the retina should be included to assess the effect of hypertension on an easily accessed end organ. In the majority of children with hypertension, however, the physical examination will be normal.

LABORATORY AND IMAGING TESTS

Laboratory testing and imaging on a child with hypertension should screen for identifiable causes, detect comorbid conditions, and evaluate end-organ damage (Table 57). Screening tests should be performed on all children with a confirmed diagnosis of hypertension. Decisions about additional testing are based on individual and family histories, the presence of risk factors, and the results of the screening tests. Young children, those with stage 2 hypertension, and those in whom a systemic condition is suspected require a more extensive evaluation because these children are more likely to have secondary hypertension. The child who is older or obese, with a family history of diabetes or other cardiovascular risk factors, will require further work-up for the metabolic abnormalities associated with primary hypertension.7

Hormone levels and 24-hour urine studies are readily available to most physicians, but more specialized tests such as renal angiography often require referral to a center with pediatric radiology, nephrology, and cardiology services. When renovascular disease is strongly suspected, conventional or intra-arterial digitally subtracted angiography are recommended. Scintography with or without angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition also can be used. These older imaging techniques are quite invasive. Data on newer studies such as magnetic resonance angiography and 3-dimensional or spiral computed tomography in children are limited, but documentation of their usefulness is increasing.7

In addition to the diagnostic tests already mentioned, an assessment of end-organ damage must be made. Retinopathy, microalbuminuria, and increased carotid artery thickness have all been reported in children with primary hypertension.4,5 Documenting LVH is an important component of the evaluation of children with hypertension.7 Because echocardiography is noninvasive, easily obtained, and more sensitive than electrocardiography,23 it should be part of the initial evaluation of all children with hypertension and may be repeated periodically.

Management

Managing childhood hypertension is directed at the cause of the elevated blood pressure and the alleviation of any symptoms. End-organ damage, comorbid conditions, and associated risk factors also influence decisions about therapy.

Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments are recommended based on the age of the child, the stage of hypertension, and response to treatment.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENTS

For children and adolescents with prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension, therapeutic lifestyle changes are recommended. These include weight control, regular exercise, a low-fat and low-sodium diet, smoking cessation, and abstinence from alcohol use.

Obesity increases the occurrence of hypertension threefold while favoring the development of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and salt sensitivity.24,27 Significant obesity also increases the likelihood of LVH independent of blood pressure level.27 Exercise has been shown to lower blood pressure in children but does not affect left ventricular function.28,29 Competitive sports are permitted for children with prehypertension, stage 1 hypertension, or controlled stage 2 hypertension in the absence of symptoms and end-organ damage.

Data regarding dietary changes in children with hypertension are limited. Nevertheless, the NHBPEP has taken an aggressive stance on sodium restriction, recommending a sodium intake of 1,200 mg per day. A no-salt-added diet with more fresh fruits and vegetables combined with low-fat dairy and protein akin to the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) food plan30 may be successful in lowering blood pressure in children. Increased intake of potassium and calcium also have been suggested as nutritional strategies to lower blood pressure.31,32 Whatever lifestyle changes are recommended, a family-centered rather than patient-oriented approach usually is more effective.7

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Reasons to initiate antihypertensive medication in children and adolescents include symptomatic hypertension, end-organ damage (e.g., LVH, retinopathy, proteinuria), secondary hypertension, stage 1 hypertension that does not respond to lifestyle changes, and stage 2 hypertension.7 In the absence of end-organ damage or comorbid conditions, the goal is to reduce blood pressure to less than the 95th percentile for age, height, and sex. When end-organ damage or coexisting illness is present, a blood pressure goal of less than the 90th percentile is recommended. Drug therapy is always an adjunct to nonpharmacologic measures.

Information about long-term, untreated childhood hypertension and the impact of antihypertensive medications on growth and development is insubstantial. According to the NHBPEP, pharmacotherapy should follow a step-up plan, introducing one medication at a time at the lowest dose, then increasing the dose until therapeutic effects are seen, side effects are seen, or the maximal dose is reached. Only then should a second agent, preferably one with a complementary mechanism of action, be initiated. Long-acting medication is useful in improving compliance, and predictable problems such as the effect of diuretic medications in young athletes should be avoided.7

The choice of initial drug therapy is largely at the discretion of the physician. Diuretics and beta blockers have documented safety and effectiveness in children. Preferential use of specific classes of medications for certain underlying or coexisting pathology has led to the prescribing of ACE inhibitors in children with diabetes or proteinuria and beta-adrenergic or calcium channel blockers for children with migraines.33 Becoming familiar with medications in each major class and with effective combinations of medications will facilitate treatment. Many medications have growing research to support their use. Those with approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in children are listed in Table 6.7 As with any chronic health issue, medical follow-up and appropriate monitoring are key to long-term success.