Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(10):1714-1720

A more recent article on Management of Acute Ankle Sprains is available.

Patient information: See related handouts on ankle sprains and ankle exercises after a sprain, written by the author of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acute ankle injury, a common musculoskeletal injury, can cause ankle sprains. Some evidence suggests that previous injuries or limited joint flexibility may contribute to ankle sprains. The initial assessment of an acute ankle injury should include questions about the timing and mechanism of the injury. The Ottawa Ankle and Foot Rules provide clinical guidelines for excluding a fracture in adults and children and determining if radiography is indicated at the time of injury. Reexamination three to five days after injury, when pain and swelling have improved, may help with the diagnosis. Therapy for ankle sprains focuses on controlling pain and swelling. PRICE (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) is a well-established protocol for the treatment of ankle injury. There is some evidence that applying ice and using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs improves healing and speeds recovery. Functional rehabilitation (e.g., motion restoration and strengthening exercises) is preferred over immobilization. Superiority of surgical repair versus functional rehabilitation for severe lateral ligament rupture is controversial. Treatment using semirigid supports is superior to using elastic bandages. Support devices provide some protection against future ankle sprains, particularly in persons with a history of recurrent sprains. Ankle disk or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation exercise regimens also may be helpful, although the literature supporting this is limited.

Acute ankle injury is one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries in athletes and sedentary persons, accounting for an estimated 2 million injuries per year and 20 percent of all sports injuries in the United States.1–3 However, many patients with ankle injuries do not seek medical attention.4 The most common acute injury is a lateral ankle inversion sprain.5 Inadequate treatment of ankle sprains can lead to chronic problems such as decreased range of motion, pain, and joint instability.6

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence Rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs help reduce swelling and pain after ankle injuries and may decrease the time it takes for the patient to return to usual activities. | B | 19,20 |

| Semirigid or lace-up ankle supports are recommended as a functional treatment for ankle injuries. | B | 22 |

| Use of semirigid or lace-up ankle supports is an option to decrease the risk of recurrent ankle injury, especially in patients with a history of recurrent sprains. | B | 28,29 |

| Graded exercise regimens, especially those involving proprioceptive elements such as ankle disk training, are recommended to help reduce the risk of ankle sprain. | B | 28,30 |

Risk Factors

There is limited evidence concerning risk factors for ankle injuries.1 A history of previous ankle sprain has been cited as a common risk factor. A prospective study of recreational basketball players demonstrated that a history of ankle sprain was a moderate risk factor for ankle injury sustained during play; wearing shoes with air cells and inadequate stretching also could play a role.4 Reported prevalence of ankle injury varies among sports and is highest in basketball, ice skating, and soccer.7 There appears to be no relationship between the type of sport and risk of ankle injury in collegiate athletics (at least among men).8 However, an athlete's sex, foot type, and generalized joint laxity may affect his or her risk of ankle injury.1,8

Diagnosis

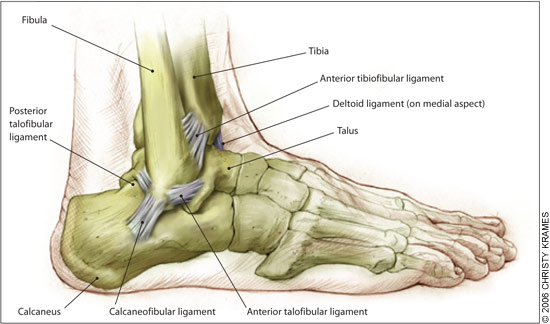

The typical ankle sprain is an inversion injury that occurs in the plantar-flexed position. Ankle sprains can be classified as grade I to III, depending on the severity of the injury (Table 1).5 The most easily injured ligaments (Figure 1) are the lateral stabilizing ligaments (i.e., anterior talofibular, calcaneofibular, and posterior talofibular).5 High ankle (syndesmotic) sprains are caused by dorsiflexion and eversion of the ankle with internal rotation of the tibia; this can injure posterior and anterior tibiofibular ligaments.

| Sign/symptom | Grade I | Grade II | Grade III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligament tear | None | Partial | Complete |

| Loss of functional ability | Minimal | Some | Great |

| Pain | Minimal | Moderate | Severe |

| Swelling | Minimal | Moderate | Severe |

| Ecchymosis | Usually not | Common | Yes |

| Difficulty bearing weight | None | Usual | Almost always |

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physicians should ask patients with ankle injuries about the mechanism and timing of the injury and if the patient has a history of recurrent sprains. Urgent evaluation is recommended for patients with a high level of pain, rapid onset of swelling, coldness or numbness in the injured foot, inability to bear weight, or a complicating condition (e.g., diabetes).10 Reexamining the patient three to five days after injury is important in distinguishing partial tears from frank ligament ruptures.11 Excessive swelling and pain can limit an examination up to 48 hours after injury.

Key physical examination findings associated with more severe grade III sprains include swelling, hematoma, pain on palpation, and a positive anterior drawer test. A systematic review showed that 96 percent of patients with all four of these findings had a lateral ligament rupture compared with only 14 percent of patients without all of these findings.11 Three clinical trials showed that the presence of these findings on physical examination is similar to arthrography in identifying lateral ligament rupture.11

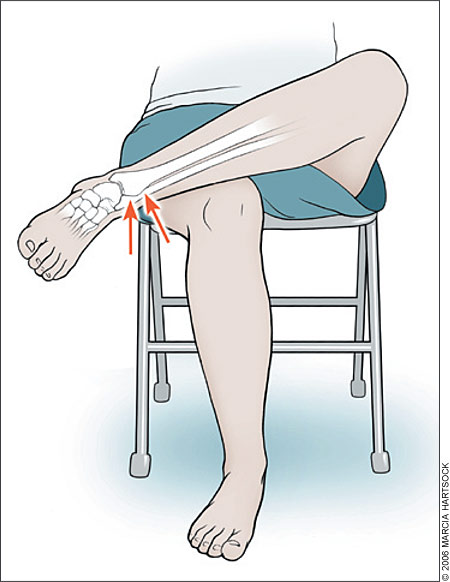

The anterior drawer test (Figure 2) can detect excessive anterior displacement of the talus onto the tibia. If the anterior talofibular ligament is torn, the talus will subluxate anteriorly compared with the unaffected ankle. A crossed-leg test (Figure 3) can detect a high ankle sprain. This injury is indicated if pressure applied to the medial side of the knee produces pain in the syndesmosis area.12 The inversion stress test or talar tilt (Figure 4) can detect calcaneofibular ligament instability.6 No definite end point or unilateral joint laxity suggests a grade III ankle sprain.

OTTAWA ANKLE AND FOOT RULES

The Ottawa Ankle and Foot Rules (Figure 5) can reduce unnecessary radiography in children and adults.13 A systematic review validated the usefulness of the rules in predicting the need for radiography.13 The review included 12 studies assessing the ankle, eight assessing the foot, 10 assessing both, and six assessing the use of the rules in children.13 The rules missed fracture in only 47 out of 15,581 patients (0.3 percent). Therefore, the rules correctly ruled out fracture, without using radiography, in 299 out of 300 patients.

Although the rules are designed for high sensitivity, their specificity is highly variable, ranging from 10 to 79 percent. Variability in clinical skill, setting, and patient recall may influence the number of unnecessary radiographs that are avoided.

Treatment

The immediate goals of treating acute ankle sprain are to decrease pain and swelling and protect ankle ligaments from further injury.14 The PRICE (Protection, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation) treatment protocol for acute ankle injury is commonly used. The protocol includes elevating the ankle and protecting it with a compressive device. Ice is applied to the injured ankle, and the patient is advised to rest for up to 72 hours to allow the ligaments to heal.

CRYOTHERAPY

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, and others recommend cryotherapy for ankle sprains, and there appears to be no strong evidence against this therapy.15 Direct application of cryotherapy helps reduce edema and probably helps decrease pain and recovery time.16 A systematic review of small, limited-quality studies evaluated cryotherapy for acute soft-tissue injuries and showed wide variations in the use and timing of the therapy.17 Cryotherapy with exercise may be somewhat beneficial, although the value of this therapy alone is unclear.17

One study of compression with cryotherapy for inversion ankle sprains suggests that patients with focal compression recover function earlier, but the study was too small to draw definitive conclusions.18 Heat is not recommended for the treatment of acute ankle injury.

NONSTEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS

Controlled trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g., piroxicam [Feldene], celecoxib [Celebrex], naproxen [Naprosyn]) in patients with ankle sprain showed that, compared with placebo, NSAIDs were associated with improved pain control and function, decreased swelling, and more rapid return to activity.19,20 A randomized controlled trial compared piroxicam with placebo in 364 Australian army recruits with ankle sprains.19 Participants who took piroxicam experienced less pain, had increased exercise endurance, and were able to return to duty more quickly.19 A placebo-controlled trial comparing celecoxib and naproxen revealed similar improvements in level of pain and ankle function in patients with ankle sprains.20

FUNCTIONAL TREATMENT

Although the overall quality of studies on functional treatment is somewhat limited, a systematic review of 21 trials (2,184 total participants) showed that functional treatment is superior to immobilization for treatment of ankle sprains.21 Five of the trials showed that, compared with immobilization, more patients undergoing functional treatment returned to sports during the study period, and two trials showed that these patients returned to sports 4.6 days sooner (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 to 7.6). Seven of the trials showed that patients undergoing functional treatment returned to work 7.1 days sooner than those treated with immobilization (95% CI, 5.6 to 8.7).21 Although the extent and type of benefit associated with functional treatment varied among individual studies, no benefits were seen with immobilization.

Functional treatment usually consists of three phases: (1) the PRICE protocol is initiated within 24 hours of injury to minimize pain and swelling and limit the spread of injury; (2) exercises to restore motion and strength usually begin within 48 to 72 hours of injury (see accompanying patient handout for exercise descriptions); and (3) endurance training, sport-specific drills, and training to improve balance begin when the second phase is well underway.

ANKLE SUPPORT

A Cochrane review showed that lace-up or semirigid supports are more effective for ankle injury than tape or elastic bandages.22 The review identified nine trials (892 total participants) that evaluated different methods of ankle support.22 When compared with the elastic bandage, the semirigid ankle support resulted in a shorter time to return to sports23 and to work22 and less ankle instability.24 The lace-up ankle support significantly decreased persistent swelling at short-term follow-up compared with the semirigid ankle support, taping, or bandaging.22 More skin irritation was reported with taping than with the other methods.22

SURGERY

Surgery versus conservative treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament sprain is controversial. A Cochrane review comparing surgical repair with a variety of conservative treatments analyzed 17 trials (1,950 total participants).25 Surgery was more favorable than conservative treatment in time to return to sports, pain, and functional instability. However, these differences were not seen when adjustments were made for the quality of studies.25 Overall pooled results of 11 clinical trials from the review showed no difference between surgery and conservative treatment in recurrence of ankle sprains; however, time to return to work was longer after surgery.25 Direct comparisons between treatment methods were difficult because of the variations in the quality of the trials.

A prospective trial followed patients with ankle ligament ruptures who were randomized to receive functional or surgical treatment.26 After eight years, fewer patients who had surgery reported residual pain (relative risk [RR] = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.41 to 1.0), chronic ankle instability (RR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.92), and recurrent sprains (RR = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.72).26 However, this trial was limited to a single health care center. There is no consensus on whether surgery is better than functional treatment for ankle injuries, although surgery may be most beneficial for patients with severe ruptures.

THERAPEUTIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Therapeutic ultrasonography appears to have no value in the treatment of acute ankle sprain. A Cochrane review examined five trials (572 total participants), although only one trial was high quality.27 None of the placebo-controlled trials demonstrated a difference between true and sham ultrasonography for any outcome measure after seven to 14 days.27

Prevention

Exercise regimens and external ankle supports usually are recommended to prevent ankle sprain. A Cochrane review identified 14 trials (8,279 total participants) that evaluated exercise training regimens and a variety of support devices.28 The review showed a 47 percent relative reduction in ankle sprains in persons who used an external ankle support and participated in high-risk sporting activities (95% CI, 40.0 to 69.0).28 This reduction was greatest for those with a history of recurrent sprains, although the therapy was beneficial even in those without a prior sprain. There was no change in the severity of ankle sprains or incidence of other leg injuries. There was some evidence that ankle disk training exercises reduced the risk of recurrent ankle sprains.28

Another review examined the effectiveness of taping and bracing in preventing recurrent ankle sprain.29 Taping was more expensive than bracing, primarily because of the time needed to apply it in the sports setting. Lace-up bracing (air cast) was beneficial for persons with previous ankle sprain. The studies were limited to athletic young adults, and the results are not necessarily applicable in older patients, children, or persons who are inactive.29

Individual studies also have evaluated proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation exercises or training regimens for injury prevention. A prospective study of Dutch volleyball players receiving proprioceptive balance board training showed significantly fewer ankle sprains in the intervention group compared with those participating in usual exercise (one fewer sprain per 2,500 playing hours).30 This difference only was observed in players with previous ankle sprains, and the intervention group had more overuse knee injuries.30 Another study included 92 patients presenting to Scandinavian emergency departments who received ankle rehabilitation training or usual care.31 After one year, fewer participants in the training group had reinjured their ankles (two out of 29 versus 11 out of 38 patients). Many patients were lost to follow-up, however.31