Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(11):1679-1688

Patient information: See related handout on chronic pancreatitis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chronic pancreatitis is the progressive and permanent destruction of the pancreas resulting in exocrine and endocrine insufficiency and, often, chronic disabling pain. The etiology is multifactorial. Alcoholism plays a significant role in adults, whereas genetic and structural defects predominate in children. The average age at diagnosis is 35 to 55 years. Morbidity and mortality are secondary to chronic pain and complications (e.g., diabetes, pancreatic cancer). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the radiographic test of choice for diagnosis, with ductal calcifications being pathognomonic. Newer modalities, such as endoscopic ultrasonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, provide diagnostic results similar to those of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Management begins with lifestyle modifications (e.g., cessation of alcohol and tobacco use) and dietary changes followed by analgesics and pancreatic enzyme supplementation. Before proceeding with endoscopic or surgical interventions, physicians and patients should weigh the risks and benefits of each procedure. Therapeutic endoscopy is indicated for symptomatic or complicated pseudocyst, biliary obstruction, and decompression of pancreatic duct. Surgical procedures include decompression for large duct disease (pancreatic duct dilatation of 7 mm or more) and resection for small duct disease. Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy is the most commonly performed surgery in patients with large duct disease. Pancreatoduodenectomy is indicated for the treatment of chronic pancreatitis with pancreatic head enlargement. Patients with chronic pancreatitis are at increased risk of pancreatic neoplasm; regular surveillance is sometimes advocated, but formal guidelines and evidence of clinical benefit are lacking.

Chronic pancreatitis is the progressive and irreversible destruction of the pancreas as characterized by permanent loss of endocrine and exocrine function. It is commonly accompanied by chronic disabling pain.1,2 Because of advances in medical imaging and more inclusive definitions, the incidence of chronic pancreatitis has quadrupled in the past 30 years.2 To effectively counsel and treat patients, primary care physicians should be familiar with treatment options, which range from chronic opioid use to endoscopic and surgical interventions.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the recommended initial imaging study in patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis. | C | 2, 5, 11, 22 |

| Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and endoscopic ultrasonography provide similar diagnostic performance as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for evaluation of pancreatic parenchyma and duct system. | C | 21–26 |

| Pancreatic enzyme supplementation is indicated for steatorrhea and malabsorption and may help relieve pain in patients with chronic pancreatitis. | B | 11, 28–31 |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography drainage of pseudocysts results in a similar rate of pain relief as surgery, with equivalent or lower mortality. | B | 11, 21, 23–25, 34–37 |

| Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy is the preferred surgical treatment in patients with pancreatic duct dilatation of 7 mm or more. | C | 2, 11, 40–42 |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure, pylorus-preserving, duodenum-preserving) is indicated in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis with pancreatic head enlargement and typically results in significant pain relief. | B | 2, 11, 43–45 |

Etiology

Because of its varied presentation and clinical similarity to acute pancreatitis, many cases of chronic pancreatitis are not diagnosed; therefore, the true prevalence is unknown.1,2 A recent Japanese study estimated a prevalence of 12 cases per 100,000 women and 45 cases per 100,000 men.3 The average age at diagnosis is 35 to 55 years. Chronic alcohol use accounts for 70 percent of the cases of chronic pancreatitis in adults, and most patients have consumed more than 150 g of alcohol per day over six to 12 years.3,4 Genetic diseases (e.g., cystic fibrosis) and anatomic defects predominate in children.5 The TIGAR-O (Toxic-metabolic, Idiopathic, Genetic, Autoimmune, Recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis, Obstructive) classification system is based on risk factors for chronic pancreatitis (Table 1).5,6

| Classification | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Toxic-metabolic | Alcohol |

| Chronic renal failure | |

| Hypercalcemia (hyperparathyroidism) | |

| Hyperlipidemia (rare) | |

| Medications* | |

| Tobacco | |

| Toxins | |

| Idiopathic | Early and late onset |

| Tropical pancreatitis (tropical calcific pancreatitis and fibrocalculous pancreatic diabetes) | |

| Genetic | Autosomal dominant (cationic trypsinogen [codon 29 and 122 mutations]) |

| Autosomal recessive modifier genes (CFTR and SPINK1 mutations, cationic trypsinogen [codon 16, 22, and 23 mutations], alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency) | |

| Autoimmune | Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, Sjögren syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis |

| Isolated autoimmune chronic pancreatitis | |

| Recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis | Postirradiation |

| Postnecrotic (severe acute pancreatitis) | |

| Recurrent acute pancreatitis | |

| Vascular ischemia | |

| Obstructive | Pancreas divisum |

| Sphincter of Oddi disorders | |

| Duct obstruction (pancreatic or ampullary tumors, posttraumatic pancreatic duct fibrosis) |

Pathophysiology

Most studies of the pathophysiology of chronic pancreatitis are performed with patients who drink alcohol. Disease characteristics include inflammation, glandular atrophy, ductal changes, and fibrosis. It is presumed that when a person at risk is exposed to toxins and oxidative stress, acute pancreatitis occurs. If the exposure continues, early- and late-phase inflammatory responses result in production of profibrotic cells, including the stellate cells. This can lead to collagen deposition, periacinar fibrosis, and chronic pancreatitis.2,5,7–9 In addition, several genetic mutations have been associated with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis.2,5,9 Autoimmune pancreatitis accounts for 5 to 6 percent of chronic pancreatitis and is characterized by autoimmune inflammation, lymphocytic infiltration, fibrosis, and pancreatic dysfunction.10

Diagnosis of Chronic Pancreatitis

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients may have recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, which can progress to chronic abdominal pain. The pain is commonly described as midepigastric postprandial pain that radiates to the back and that can sometimes be relieved by sitting upright or leaning forward. In some patients there is a spontaneous remission of pain by organ failure (pancreatic burnout theory).2,11–13 Patients may also present with steatorrhea, malabsorption, vitamin deficiency (A, D, E, K, B12), diabetes, or weight loss.1,4,11,14,15 Approximately 10 to 20 percent of patients may have exocrine insufficiency without abdominal pain.1,4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Chronic pancreatitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with acute or chronic abdominal pain of unknown etiology. Elevations in serum amylase and lipase levels are nonspecific and can occur with mesenteric ischemia, biliary disease, complicated peptic ulcers, and renal insufficiency (Table 2).2,4,16–18

| More common |

| Acute cholecystitis |

| Acute pancreatitis |

| Intestinal ischemia or infarction |

| Obstruction of common bile duct |

| Pancreatic tumors |

| Peptic ulcer disease |

| Renal insufficiency |

| Less common |

| Acute appendicitis |

| Acute salpingitis |

| Crohn's disease |

| Ectopic pregnancy |

| Gastroparesis |

| Intestinal obstruction |

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Malabsorption |

| Ovarian cysts |

| Papillary cystadenocarcinoma of ovary |

| Thoracic radiculopathy |

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is made based on the clinical presentation and imaging studies, especially in advanced disease. However, no single test is diagnostic for early chronic pancreatitis, and each test should be used based on availability and the risks and benefits to the patient (Table 3).1,2,5,10,16,18–20

| Tests | Comments | |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | Elevated with infection, abscess | |

| Serum amylase and lipase | Nonspecific for chronic pancreatitis1,2,16,18 | |

| Total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and hepatic transaminase | Elevated in biliary pancreatitis and ductal obstruction by strictures or mass16 | |

| Fasting serum glucose | Elevation suggests pancreatic diabetes2 | |

| Pancreatic function tests | Sometimes useful in early chronic pancreatitis with normal computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging1,2,5,19,20 | |

| Fecal fat estimation | > 7 g fat per day is abnormal; quantitative; requires 72 hours; should be on a diet of 100 g fat per day1,2,5 | |

| Fecal elastase | < 200 mcg per g (0.20 g per kg) of stool is abnormal; noninvasive; exogenous pancreatic supplementation will not alter results; requires only 20 g of stool2,5,19 | |

| Secretin stimulation | Peak bicarbonate concentration < 80 mEq per L (80 mmol per L) in duodenal secretion; best test for diagnosing pancreatic exocrine insufficiency1,2,5,20 | |

| Serum trypsinogen | < 20 ng per mL (0.83 nmol per L) is abnormal2,5 | |

| Lipid panel | Significantly elevated triglycerides are a rare cause of chronic pancreatitis2 | |

| Calcium | Hyperparathyroidism is a rare cause of chronic pancreatitis2 | |

| Immunoglobulin G4 serum antibody, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Abnormality may indicate autoimmune pancreatitis10 | |

Laboratory Testing. During episodes of acute pancreatitis, pancreatic enzyme levels are typically elevated more than three times the upper limits of normal16,18; however, in most cases, serum amylase and lipase levels may be normal or only mildly elevated.1 Jaundice and elevated bilirubin, serum alkaline phosphatase, and hepatic transaminase levels occur with obstruction of the biliary tract.16

Pancreatic function tests are not diagnostic; they are most helpful when used in patients with suspected chronic pancreatitis who have normal computed tomography (CT). Additionally, pancreatic function tests are not specific for diagnosis and are difficult to perform; therefore, they are not routinely recommended.1,2,5,11,19,20 Although the secretin stimulation test is the most sensitive, it is not widely available.

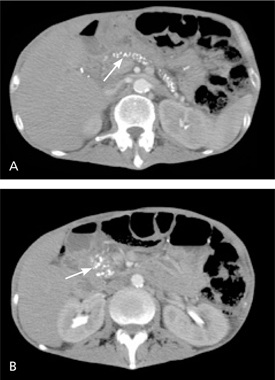

Imaging Studies. Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is still used as the reference standard in studies,5,21 contrastenhanced CT of the abdomen is the initial imaging modality of choice.11 Pathognomonic findings on plain radiography and CT reveal calcifications within the pancreatic ducts (Figure 1). Pseudocysts, ductal dilatation, thrombosis, pseudoaneurysms, necrosis, and parenchymal atrophy can also be detected by CT.3,22

For evaluation of the pancreatic parenchyma and duct system, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) provide diagnostic performance similar to ERCP.21–24 Because of the high risk of complications (e.g., pancreatitis, hemorrhage, infection), ERCP is rarely recommended for diagnosis.2,21–23 EUS has a sensitivity of 97 percent and a specificity of 60 percent, and it has emerged as a first-line diagnostic test for early chronic pancreatitis and evaluation of cystic or mass lesions. Given a pretest probability of 50 percent, 70 percent of patients with positive EUS have chronic pancreatitis, and 95 percent with a negative test do not. Additionally, the complication rates with EUS are low; 2 to 3 percent of patients develop pancreatitis, and less than 1 percent develop hemorrhage and infection.21,22,25,26 The accuracy of diagnostic tests is summarized in Table 4.2,5,11,19–26

| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain abdominal radiography | NA | NA | Not routinely recommended; calcifications may be visible |

| Ultrasonography | NA | NA | Rarely diagnostic; may be useful for ultrasonography-guided aspiration of cyst |

| Contrast-enhanced computed tomography | 75 to 90 | 85 | Initial radiologic test of choice for evaluation of suspected chronic pancreatitis; can visualize calcifications, pseudocysts, thrombosis, pseudoaneurysms, necrosis, and atrophy2,5,11,22 |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography | 75 to 95 | 90 | Reference standard in many studies; invasive and associated with complications; mainly used in diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis with normal computed tomography and pancreatic function tests5,11,21–23 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography | 85 | 100 | Noninvasive and nonionizing radiation or contrast media; less sensitive than endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for evaluation of side branches; can be combined with secretin test21–24 |

| Endoscopic ultrasonography | 97 | 60 | Useful in evaluation of early chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic mass, and cystic lesions; can be combined with fine-needle aspiration biopsy2,11,19,20,25,26 |

APPROACH TO THE PATIENT WITH SUSPECTED CHRONIC PANCREATITIS

Because patients with chronic pancreatitis may have varied clinical presentations, there should be a high index of suspicion. One suggested approach to the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is shown in Figure 2.2,5,11,15–26 CT can identify most cases of large duct disease (pancreatic duct dilatation of 7 mm or more) and is the initial diagnostic test of choice.2,5,22 In patients with stones, stricture, or pseudocyst, MRCP or EUS can be performed to identify the ductal anatomy before ERCP or surgery.21–24 Patients with early or small duct disease (pancreatic duct dilatation less than 7 mm) pose a diagnostic problem because initial imaging tests (CT or magnetic resonance imaging) can be normal. EUS with fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) and pancreatic function tests can be performed in patients with suspected early chronic pancreatitis.2,5,11,19,20,26 EUS alone may overestimate disease because many of the early endoscopic changes with chronic pancreatitis can be identified in normal aging.2,5,26 EUS combined with FNAB is the recommended tool for evaluation of cystic or mass lesions to determine malignancy. Fluid also can be analyzed for tumor markers, such as carbohydrate antigen 19-9.2,25,26

Treatment

Management options for chronic pancreatitis include medical, endoscopic, and surgical treatments (Table 5).2,11,13–15,21,23–25,27–45 Although widely used, many surgical and endoscopic options have not been compared with conservative medical treatments; therefore, the physician and patient must carefully weigh the risks and benefits of each intervention.11

| Treatment type | Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical | Analgesics (stepwise approach) | |

| Antidepressants (treatment of concurrent depression) | ||

| Cessation of alcohol and tobacco use | ||

| Denervation (celiac nerve blocks, transthoracic splanchnicectomy) | ||

| Insulin (for pancreatic diabetes) | ||

| Low-fat diet and small meals | ||

| Pancreatic enzymes with proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2 blockers | ||

| Steroid therapy (in autoimmune pancreatitis) | ||

| Vitamin supplementation (A, D, E, K, and B12) | ||

| Endoscopic | Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy with or without endoscopy | |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy and stent placement for pain relief | ||

| Transampullary or transgastric drainage of pseudocyst | ||

| Surgical | ||

| Decompression | Cystenterostomy | |

| Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (most common) | ||

| Sphincterotomy or sphincteroplasty | ||

| Resection | Distal or total pancreatectomy | |

| Pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure, pylorus-preserving, duodenum-preserving) | ||

| Not recommended | Allopurinol (Zyloprim) | |

| Antioxidant therapy (vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium [Selepen*], methionine [Uracid]) | ||

| Octreotide (Sandostatin) | ||

| Prokinetic agents (erythromycin) | ||

MEDICAL

Chronic disabling pain is responsible for most of the morbidity of chronic pancreatitis; thus, treatment is directed toward pain relief and management of complications.11,27 The mainstay of treatment is lifestyle modification (e.g., cessation of alcohol and tobacco use) and dietary changes (e.g., low-fat diet, eating small meals).2,11 Treatment options consist of analgesics coupled with antidepressants to address the concurrent depression. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen are the first-line agents for use in a stepwise approach with long-acting and short-acting narcotics. However, narcotic addiction is a common consequence of treatment and should be closely monitored, perhaps in consultation with a pain specialist.

Pancreatic enzymes (approximately 40,000 units of lipase) are recommended for the treatment of steatorrhea and malabsorption.11,28–31 Evidence on the effect of pancreatic enzymes on pain control has been conflicting because of the heterogeneity of the studies and types of preparation (enteric-coated versus nonenteric-coated tablets). For example, in one meta-analysis, only two of six studies showed a benefit in pain control with pancreatic enzymes.28 Other studies found that nonenteric-coated preparations (four to eight tablets) taken during or after meals do have some benefit in pain control, especially in patients with small duct disease.2,11,28–30

Treatment with acid suppression agents, a histamine H2 blocker, or a proton pump inhibitor reduces inactivation of the enzymes from gastric acid.11,32 Antioxidant therapy has been shown to reduce pain in a small randomized trial with a heterogeneous group of 36 patients, only 19 of whom completed the study. Given the study's limitations, further study is required before this therapy is widely adopted.11,33 Three trials of octreotide (Sandostatin) and a single trial of allopurinol (Zyloprim) have not shown any significant benefit.11 Denervation of splanchnic nerves and celiac plexus have been reported to achieve pain relief, but long-term outcomes are unclear.11 Finally, although vitamin D deficiencies with chronic pancreatitis are rare, recent reports have suggested an increased risk of vitamin D deficiency; therefore, one-time screening for bone density and vitamin D levels may be considered.13,15

The decision to move to endoscopic or surgical interventions should be considered for treatment of correctable causes and when medical management no longer relieves pain, when quality of life is greatly decreased, or when patients are significantly malnourished.

ENDOSCOPY

Therapeutic indications for ERCP include treatment of symptomatic stones, strictures, and pseudocysts. Ductal decompression by sphincterotomy or stent placement offers pain relief in most patients.11,21,23 Endoscopic drainage is indicated for symptomatic or complicated pseudocysts; regression occurs in 70 to 86 percent of these patients.21,23–25,34–37 ERCP drainage of pseudocysts results in a rate of pain relief similar to that of surgery, with equivalent or lower mortality.21,23–25,34–37 In patients with significant stone burden, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, with or without endoscopic drainage of the pancreatic duct, has been proposed as a safe technique. Although studies have yielded conflicting results, recent meta-analyses concluded that the technique is effective for duct clearance and pain relief.11,21,38,39

SURGERY

One half of all patients will undergo surgery during the course of their disease.1 Most patients undergo surgery when the initial medical and endoscopic treatments fail to relieve intractable abdominal pain. Surgery is also indicated for obstruction of surrounding structures, hemorrhage, and suspected neoplasia (Table 6).2,11,44

| Biliary or pancreatic stricture |

| Duodenal stenosis |

| Fistulas (peritoneal or pleural effusion) |

| Hemorrhage |

| Intractable chronic abdominal pain |

| Pseudocysts |

| Suspected pancreatic neoplasm |

| Vascular complications |

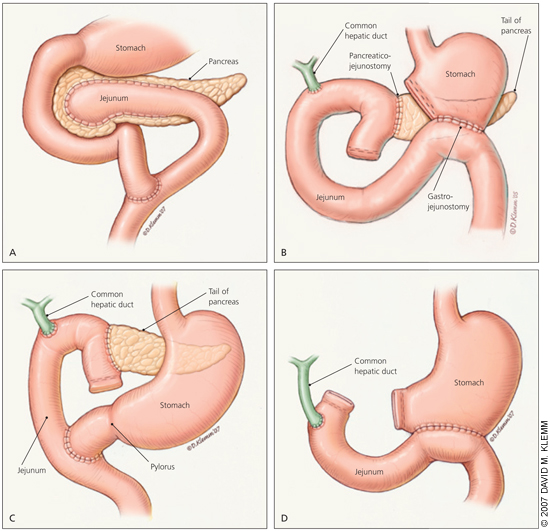

Decompression procedures are used in patients with large duct disease. Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Figure 3A) is commonly performed and yields pain relief in 60 to 91 percent of patients2,40,41; recent studies have found it to be more effective than endoscopic drainage for long-term pain relief.42 Cystenterostomy is indicated for symptomatic, enlarging, or complicated pseudocyst; it has a success rate of 90 to 100 percent.43 Because of a higher mortality rate, percutaneous drainage is reserved for high-risk surgical patients and those who do not improve with endoscopic approaches.37,44

Resective procedures are considered in patients with pancreatic mass or small duct disease. Resective procedures include pancreatoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure [Figure 3B], pylorus-preserving [Figure 3C], and duodenum-preserving) and distal or total pancreatectomy (Figure 3D).45 The Whipple procedure has been the most widely performed surgery in patients with chronic pancreatitis. It provides pain relief in 85 percent of patients, with mortality rates of less than 3 percent.45 Distal pancreatectomy is associated with an increased risk of early-onset diabetes and is only indicated if the disease is confined to the tail of the pancreas.13 Total pancreatectomy is a last-resort procedure associated with a high rate of brittle diabetes and inadequate pain relief and, therefore, should be accompanied by autologous islet cell transplantation.2,45,46 Patients should be counseled about inadequate pain relief, complications, and increased rate of exocrine and endocrine insufficiency before proceeding with surgery.5,11

Complications

Morbidity and mortality are typically caused by debilitating pain, progression to diabetes, and pancreatic cancer,11 with mortality being caused mainly by cardiovascular events and sepsis.2,4 Most patients will develop diabetes, with an onset about five years after the initial diagnosis.4,7,13 Most pseudocysts are asymptomatic, but they can cause complications in 25 to 30 percent of patients and can result in rupture, infection, intracystic bleeding, and obstruction of the surrounding structures.24 Rarely, portal hypertension and gastric varices result from thrombosis of the splenic vein; this can cause pseudo-aneurysms to form, especially in the splenic artery. Episodes of acute pancreatitis can cause pancreatic abscesses, necrosis, sepsis, and multiorgan failure.18 There is a 15-fold risk of pancreatic cancer for patients with chronic pancreatitis who are alcoholics and a 40 percent lifetime risk for those with hereditary disease.47 Complications of chronic pancreatitis are summarized in Table 7.2,4,7,11,13,15–18,24,26,27,47

| Complication | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Acute pancreatitis | Recurrent |

| Chronic pain | 80 to 90 |

| Diabetes mellitus | > 40 |

| Weight loss | > 40 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 15 to 40 |

| Pseudocyst | 25 to 30 |

| Malabsorption and steatorrhea | 10 to 15 |

| Bile duct, duodenal, or gastric obstruction | 5 to 10 |

| Pancreatic ascites or pleural effusion | < 10 |

| Splenic or portal vein thrombosis | < 1 |

| Pseudoaneurysm, especially of splenic artery | < 1 |

| Vitamin deficiency (A, D*, E, K and B12) | Rare |

Surveillance

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend screening average-risk persons for pancreatic neoplasm.48 However, patients with chronic pancreatitis, especially hereditary pancreatitis, have an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.47,49 Hence, some experts have recommended offering screening and counseling to patients with hereditary pancreatitis who are older than 40 years.50 Patients presenting with a change in their pain pattern, weight loss, and jaundice should also be evaluated for cancer.50 Dual-phase helical CT is 98 percent sensitive (i.e., 98 percent of patients with malignancy will have an abnormal test) but relatively nonspecific; it is a good initial test for patients with suspected malignancy.47 In patients with a negative CT result but in whom there is a high index of suspicion, EUS-guided FNAB, ERCP, and tumor markers may be considered.47,50 Patients should be counseled against continued use of alcohol and tobacco because both increase the risk of developing pancreatic cancer.50