A more recent article on birthmarks in newborns is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):56-60

This is part II of a two-part article on newborn skin. Part I, “Common Rashes,” appears in this issue of AFP on page 47.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Birthmarks in newborns are common sources of parental concern. Although most treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion, limited evidence exists to guide management of these conditions. Large congenital melanocytic nevi require evaluation for removal, whereas smaller nevi may be observed for malignant changes. With few exceptions, benign birthmarks (e.g., dermal melanosis, hemangioma of infancy, port-wine stain, nevus simplex) do not require treatment; however, effective cosmetic laser treatments exist. Supernumerary nipples are common and benign; they are occasionally mistaken for congenital melanocytic nevi. High- and intermediate-risk skin markers of spinal dysraphism (e.g., dermal sinuses, tails, atypical dimples, multiple lesions of any type) require evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasonography. Family physicians should be familiar with various birthmarks and comfortable discussing disease prevention and cosmetic strategies.

Birthmarks can be divided into three groups: pigmented birthmarks, vascular birthmarks, and birthmarks resulting from abnormal development. Nearly all birthmarks are of concern to parents, and some may require further work-up for underlying defects or malignant potential. Part II of this two-part article reviews the identification and management of birthmarks that appear in the neonatal period, with an emphasis on prognosis and appropriate counseling for parents. Part I of this article, which appears in this issue of AFP, discusses the presentation, prognosis, and treatment of common rashes that present during the first four weeks of life.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi should be referred to a surgeon and followed for recurrence. | C | 2, 4 |

| Uncomplicated hemangiomas that are not near the eyes, lips, nose, or perineum do not require treatment. | C | 12 |

| Infants with port-wine stains near the eyes should be referred for glaucoma testing. | C | 18 |

| Patients with multiple midline lumbosacral skin lesions or a single high-risk lesion should undergo magnetic resonance imaging or ultrasonography to rule out occult spinal dysraphism. | C | 24, 25 |

Pigmented Birthmarks

CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI

Congenital melanocytic nevi occur in 0.2 to 2.1 percent of infants at birth.2 They are thought to arise from disrupted migration of melanocyte precursors in the neural crest. Colors range from brown to black. Most of these lesions are flat, but raised nevi may also occur.

Congenital melanocytic nevi present difficult management decisions for parents and physicians because of their potential for malignancy. A systematic review of studies of patients with mostly large lesions showed that melanoma developed in 0.5 to 0.7 percent of patients.2,3 The mean age at diagnosis of melanoma was 15.5 years (median, seven years; range, birth to 57 years).2

The predicted size of lesions in adulthood is the most useful prognostic factor (Table 1).2,4 Giant congenital melanocytic nevi (i.e., “garment nevi”) are larger than 40 cm in adulthood and carry the highest risk of malignancy2 (Figure 1). Large lesions (20 to 40 cm in adulthood) occur in 0.025 percent of newborns and carry a 4 to 6 percent lifetime risk of malignancy.3 Greater numbers of satellite nevi near a large lesion also increase risk.5 Smaller nevi are not well studied, but lesions that are projected to grow to less than 1.5 cm in adulthood rarely progress to melanoma.

| Size | Size during infancy | Projected size in adulthood | Management strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giant | >14 cm | > 40 cm | Remove nevus, observe for recurrence in original or distal sites |

| Large | > 7 cm on torso, buttocks or extremities; >12 cm on head | 20 to 40 cm | Remove nevus, observe for recurrence in original or distal sites |

| Medium | 0.5 to 7 cm | 1.5 to 20 cm | Consider referral to dermatologist for observation |

| Small | < 0.5 cm | < 1.5 cm | Observe in primary care setting |

Nevi invariably change as a child grows, making evaluation challenging. Nevertheless, any nevus that changes in color, shape, or thickness warrants further evaluation to rule out melanoma. Prophylactic removal of high-risk lesions does not guarantee protection from melanoma. Recurrence at the original site is possible. In addition, one third of melanomas arise in different sites from the original nevus.2 Thus, patients must be followed regularly, even after the congenital melanocytic nevus is removed.6

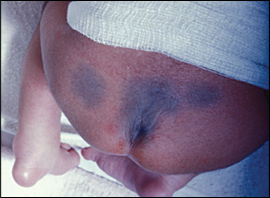

DERMAL MELANOSIS

Dermal melanosis is another type of pigmented birthmark. Commonly known as “mongolian spots,” these flat bluish-gray or brown lesions arise when melanocytes are trapped deep in the skin (Figure 2). These lesions most often occur on the back or buttocks and may easily be mistaken for bruises. The incidence of dermal melanosis varies widely among racial and ethnic groups; they are more common in black, Native American, Asian, and Hispanic populations.7 Because the “bruise” appearance may raise suspicion for child abuse in some settings, dermal melanosis should be documented in the medical record. Most lesions fade by two years of age and do not require treatment.8,9

Vascular Birthmarks

HEMANGIOMAS

Hemangiomas of infancy are often referred to as strawberry hemangiomas (Figure 3). They occur in 1.1 to 2.6 percent of newborns.10 At birth, these lesions may be clinically unapparent or marked by only a pale patch of skin. Infants can develop hemangiomas anytime in the first few months of life; they are present in 10 percent of infants at one year of age.11 Hemangiomas of infancy tend to involute and disappear after infancy; 50 percent of hemangiomas resolve by five years of age, 70 percent by seven years of age, and 90 percent by 10 years of age.11

Hemangiomas may leave residual atrophy, telangiectasias, hypopigmentation, or scars. Treatment during the first year with pulsed dye laser may hasten clearance by school age. However, the only randomized controlled trial with blinded assessment of results failed to show any long-term cosmetic benefit with this therapy.12 Additional studies are needed, especially for facial hemangiomas, to confirm whether early treatment improves cosmetic outcomes.

Hemangiomas that compress the eye, airway, or vital organs require immediate referral in the neonatal period. These lesions generally respond to treatment with prednisone at a dosage of 3 mg per kg daily for six to 12 weeks.13

Rarely, large or multiple hemangiomas can lead to high-output heart failure. Sacral hemangiomas may be associated with tethered cord syndrome or neurologic deficits.14 Deep hemangiomas require evaluation of underlying structures and a complete physical examination. Multiple cutaneous hemangiomas should alert physicians to the possibility of hemangiomas in the liver and gastrointestinal tract, which could cause obstruction or bleeding.

NEVUS FLAMMEUS

Nevus flammeus (also known as port-wine stain) is a vascular birthmark that occurs in 0.3 percent of newborns8 (Figure 4). These flat lesions are dark red to purple and are readily apparent at birth. Unlike hemangiomas, they generally do not fade over time, and may even deepen in color. They may also develop varicosities, nodules, or granulomas. Port-wine stains do not require treatment, but pulsed dye laser therapy can be used to lighten lesions if cosmesis is a concern. The optimal timing of treatment is before one year of age. In one study, five sessions of pulsed dye laser therapy reduced lesion size by 63 percent, whereas additional treatments reduced lesions less dramatically (18 percent).15 Two-week intervals between treatments seem to be as effective and well-tolerated as longer intervals.16

Port-wine stains in the ophthalmic (V1) distribution of the trigeminal nerve are associated with ipsilateral glaucoma. Glaucoma may occur alone or as part of Sturge-Weber syndrome, which occurs in 5 to 8 percent of patients with ophthalmic port-wine stains. It is classically defined by the triad of glaucoma, seizures, and port-wine stain, and it involves angiomas of the brain and meninges. Patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome are at increased risk of mental retardation and hemiplegia.17 Physicians should refer infants with port-wine stains near the eye to an ophthalmologist for glaucoma testing.18

NEVUS SIMPLEX

Nevus simplex is a vascular birthmark that occurs in 33 percent of newborns.8 Commonly known as “stork bites,” “angel kisses,” or “salmon patches,” these flat, salmon-colored lesions are caused by telangiectasias in the dermis. They occur over the eyes, scalp, and neck, and they blanch when compressed. In contrast with port- wine stains, which are usually unilateral, salmon patches often occur on both sides of the face in a symmetric pattern. They are benign lesions of no clinical significance; 40 percent resolve in the neonatal period, and most resolve by 18 months of age.8

Other Birthmarks

SUPERNUMERARY NIPPLES

During embryogenesis, nipples arise from a pair of mammary ridges extending along the ventral body wall from midaxilla to the inguinal area. Extra mammary glands may also arise from these ridges, leading to supernumerary nipples. Supernumerary nipples may be unilateral or bilateral, and they may include an areola, nipple, or both. Because of their pigmentation, they occasionally may be mistaken for congenital melanocytic nevi.

One large study of children presenting for routine well-child care showed that 5.6 percent of children exhibit one or more supernumerary nipple.19 Of note, these investigators included small supernumerary nipples with an areola but no nipple, which may be missed on cursory physical examination.

Supernumerary nipples are generally thought to be benign. Some studies have suggested an association with renal or urogenital anomalies, whereas other studies have failed to show this association.20,21 There is insufficient evidence to recommend imaging studies or removal in the absence of other clinical concerns or physical findings.

SKIN MARKERS OF SPINAL DYSRAPHISM

Spinal dysraphism is a diverse spectrum of congenital spinal anomalies caused by incomplete fusion of the midline elements of the spine. Although some anomalies, such as myelomeningocele, are readily apparent at birth, other defects are covered by skin and are difficult to detect. Tethered cord syndrome is an especially problematic form of occult spinal dysraphism; failure to detect and surgically release a tethered cord can lead to excessive traction on the cord and neurologic compromise.22

Midline lumbosacral skin lesions (e.g., lipomas, dimples, dermal sinuses, tails, hemangiomas, hypertrichosis) are cutaneous markers of spinal dysraphism.22 A comprehensive review of 200 patients with spinal dysraphism found that 102 had a cutaneous sign.23 However, many children without spinal dysraphism also have these skin findings.

Patients with high- or intermediate-risk midline lumbosacral lesions should undergo imaging, as should those with multiple lesions of any type (Table 2).24 The presence of two or more congenital midline skin lesions is the strongest predictor for spinal dysraphism.24 Lipomas, dermal sinuses, and tails are high-risk lesions.24 Given the catastrophic neurologic consequences of missed diagnoses, physicians often perform imaging in patients with any high-risk lesion.

| Skin lesion | Risk of occult spinal dysraphism | Suggested evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any one of the following: | High | MRI | |

| Dermal sinus | |||

| Lipoma | |||

| Tail | |||

| Any one of the following: | Intermediate | MRI or ultrasonography | |

| Aplasia cutis congenita | |||

| Atypical dimple | |||

| Deviation of gluteal furrow | |||

| Any one of the following: | Low | No evaluation needed in most cases; may consider ultrasonography depending on local standard of care | |

| Hemangioma | |||

| Hypertrichosis | |||

| Mongolian spot | |||

| Nevus simplex | |||

| Port-wine stain | |||

| Simple dimple | |||

| Two or more lesions of any type | High | MRI | |