Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(10):1107-1114

A more recent article on tendinopathies of the foot and ankle is available.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Because our understanding of tendinopathy has evolved in recent years, the condition is now considered a degenerative process; this affects the approach to treatment. Initial therapy should always involve relative rest and modification of physical activity, use of rehabilitative exercises, and evaluation of intrinsic and extrinsic causes of injury. The posterior tibial tendon is a dynamic arch stabilizer; injury to this tendon can cause a painful flat-footed deformity with hindfoot valgus and midfoot abduction (characterized by the too many toes sign). Treatment of posterior tibial tendinopathy is determined by its severity and can include immobilization, orthotics, physical therapy, or subspecialty referral. Because peroneal tendinopathy is often misdiagnosed, it can lead to chronic lateral ankle pain and instability and should be suspected in a patient with either of these symptoms. Treatment involves physical therapy and close monitoring for surgical indications. Achilles tendinopathy is often caused by overtraining, use of inappropriate training surfaces, and poor flexibility. It is characterized by pain in the Achilles tendon 4 to 6 cm above the point of insertion into the calcaneus. Evidence from clinical trials shows that eccentric strengthening of the calf muscle can help patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy is most common among ballet dancers. Patients may complain of an insidious onset of pain in the posteromedial aspect of the ankle; treatment involves correcting physical training errors, focusing on body mechanics, and strengthening the body's core. Anterior tibial tendinopathy is rare, but is typically seen in patients older than 45 years. It causes weakness in dorsiflexion of the ankle; treatment involves short-term immobilization and physical therapy.

Primary care physicians commonly see patients with musculoskeletal injuries. Among the most difficult to treat are overuse tendon injuries (tendinopathies) of the foot and ankle. When patients present with foot and ankle pain, tendinopathies are often missed and assumed to be just an ankle sprain, which can lead to chronic pain and deformity.1 This article reviews the diagnosis and treatment of tendinopathies of the foot and ankle (Table 1).

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen provide short-term pain relief for patients with tendinopathy but do not affect long-term outcomes. | B | 8, 12 |

| Protection, relative rest, ice, compression, elevation, medications, and rehabilitative exercise modalities to promote healing and pain relief should be recommended for tendinopathy. There are no clear recommendations for the duration of relative rest. | C | 1, 9, 13 |

| Eccentric strength training is an effective therapy for Achilles tendinosis and may reverse degenerative changes. | B | 8, 14–16 |

| Treatment of posterior tibial tendinopathy should be based on the severity of dysfunction; improper therapy can lead to a painful flat-footed deformity. | B | 33, 36–38 |

| Condition | Diagnosis | Differential diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior tibial tendinopathy | Pain and swelling posterior to the medial malleolus Pain worse with weight bearing and with inversion and plantar flexion against resistance | Deltoid ligament sprain Flexor digitorum longus injury Flexor hallucis longus injury Navicular stress fracture Tarsal tunnel syndrome | PRICEMM Foot orthosis to decrease pronation Posterior tibial tendon strengthening Consider immobilization in short leg cast for two to three weeks |

| Peroneal tendinopathy | Pain and swelling posterior to the lateral malleolus Pain with active eversion and dorsiflexion against resistance May have a history of chronic lateral ankle pain and instability | Ankle sprain Fibular fracture Peroneal subluxation or dislocation Os perineum syndrome | PRICEMM Foot orthotic Lateral heel wedge Eversion strengthening |

| Achilles tendinopathy | Pain, swelling, and/or crepitus at the tendon (often 3 to 5 cm above insertion to calcaneus) Recent change in intensity or duration of training Hamstring and gastrocnemius-soleus complex-soleus inflexibility | Achilles rupture (partial or complete) Retrocalcaneal bursitis | PRICEMM Gastrocnemius and soleus stretching Eccentric strengthening program |

| Flexor hallucis longus tendinopathy | Pain and swelling over the posteromedial aspect of the ankle Seen in dancers or athletes who use repetitive push-off maneuver Pain with resistive flexion of the great toe | Osteoarthritis Osteochondritis of talus Posterior impingement Posterior tibial tendinopathy | PRICEMM Shoe with a firm sole Core strengthening |

| Anterior tibial tendinopathy | Pain over the anterior ankle Weak dorsiflexion of the foot Caused by forced dorsiflexion | Anterior tibial rupture Lumbar radiculopathy Peroneal nerve palsy | PRICEMM Immobilization in short leg cast Dorsiflexor strengthening |

Anatomy and Biomechanics

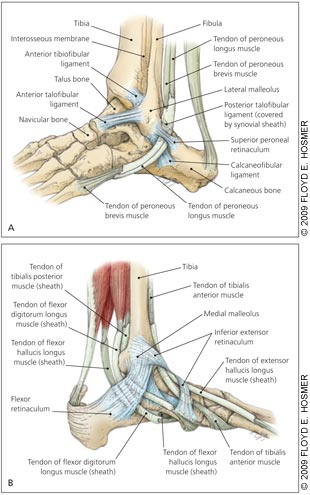

Biomechanics of the foot and ankle involve understanding their anatomy (Figure 1) and the gait cycle. The gait cycle describes what happens to the foot and ankle from the point of initial contact with the ground and heel strike to the point at which the same foot hits the ground again. It is divided into the stance phase (60 percent of cycle, when the foot is in contact with the ground) and the swing phase (40 percent of cycle, when the foot is not in contact with the ground). At heel strike, the foot is supinated; immediately after the foot begins to pronate. At midstance, the foot should be maximally pronated. This pronation is normal as the subtalar joint unlocks so the foot can become flexible, allowing for accommodation to the ground surface. As the body weight shifts forward, the foot begins to return to a neutral position in preparation for heel lift. Heel lift occurs at the end of the stance phase and the foot supinates. Supination results in the formation of a rigid subtalar joint that facilitates an efficient toe off. Abnormalities in the gait cycle can contribute to the development of tendinopathies, especially in the foot and ankle.

Pathophysiology of Tendinopathies

Recent data have demonstrated that overuse tendon injuries are not caused by persistent inflammation.2,3 The term tendinopathy is commonly used for overuse tendon injuries in the absence of a pathologic diagnosis and describes a spectrum of diagnoses involving injury to the tendon (e.g., tendinitis, peritendinitis, tendinosis).4–6 These overuse injuries are most likely to occur when the mode, intensity, or duration of physical activity or athletic training changes in some way. A period of recovery is necessary to meet the increased demands on the tissues; inadequate recovery is thought to lead to breakdown at the cellular level.7

A normal response to tendon injury consists of inflammation (i.e., tendinitis) followed by deposition of collagen matrix within the tendon and remodeling (i.e., tendinosis). However, a failed healing response may occur because of ongoing mechanical forces on the tendon, poor blood supply, or both. The tendon undergoes microscopic changes, including fibrin deposition, neovascularization, reduction in neutrophils and macrophages, and an increase in collagen breakdown and synthesis.8–10 The resultant tissue consists of a disorganized matrix of hypercellular, hyper-vascular tissue that is painful and weak.

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with tendinopathy present with an insidious onset of pain over the affected tendon that worsens with sustained activity. In the early stages of disease, pain decreases with a warm-up period; in later stages, pain may be present at rest but worsens with activity. The pain is less severe during prolonged rest periods. There is often a history of trauma, involvement in a new sport or exercise, or an increase in the intensity of physical activity. Pain is usually described as dull at rest, and sharp with the aggravating activity. No systemic symptoms should be present.

The physician should observe the affected area, noting asymmetry, swelling, or muscle atrophy. The presence of an effusion suggests an intra-articular disorder rather than tendinopathy. Decreased range of motion is seen on the affected side. Palpation may reveal tenderness along the tendon, reproducing the patient's pain. It is important to view the biomechanical alignment of the foot and ankle while the patient is standing and throughout the gait cycle. Pain in multiple tendons or joints may represent a rheumatologic cause.

IMAGING

Plain radiography is recommended as the initial imaging study. Results are usually normal, but the study may reveal calcification of the tendon, osteoarthritis, or a loose body. Further imaging should be considered if the patient fails to respond to conservative management, the diagnosis remains unclear, or there is pain out of proportion to the injury. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography can show areas of tendinosis and is useful for obtaining a dynamic examination. Magnetic resonance imaging also provides good images of tendon pathology, especially if surgical evaluation is being considered.

Treatment

Outside of the acute setting, tendon injuries are not inflammatory in nature, so physicians should not use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) alone in treatment. Acetaminophen should be used initially for pain relief because it has fewer adverse effects and there is no evidence that NSAIDs are more effective than acetaminophen.11 NSAIDs do not speed recovery from tendon injury and may interfere with that process.1,8,9 Acetaminophen and NSAIDs provide short-term pain relief for patients with tendinopathy, but do not affect long-term outcomes.1,8,9,12

Treatment of tendinopathies ranges from relative rest to surgical debridement. However, many therapies have not been studied in clinical trials, and it is not known whether the same treatment options can be applied to all tendinopathies. Treatment should always start with conservative measures, including protection, relative rest, ice, compression, elevation, medications, and rehabilitative exercise modalities (PRICEMM).1,9,13 Patients should be encouraged to reduce their level of physical activity to decrease repetitive loading on the tendon. Duration of relative rest depends on the injury and the patient's activity level.1,9,13 Rehabilitative exercises involve a stretching and strengthening program and should be initiated early.

Eccentric strength training, which involves actively lengthening the muscle, is an effective therapy that helps promote the formation of new collagen. Eccentric exercise has proved beneficial in the treatment of Achilles and patellar tendinosis, and it may be helpful in other tendinopathies as well.8,14–16 Other physical therapy modalities include ultrasound, iontophoresis (electric charge to drive medication into the tissues), and phonophoresis (use of ultrasound to enhance the delivery of topically applied drugs), but little evidence exists on their effectiveness in treating tendinopathy.12

It is important to consider and treat the extrinsic and intrinsic causes of tendon injury. Extrinsic factors include overuse of the tendon, training errors, smoking, medication abuse, and wearing shoes or other equipment not appropriate for the specific activity. This includes not wearing the appropriate type of shoe (i.e., motion control, cushioned, and stability) for the patient's foot type. Intrinsic factors such as flexibility and strength of the tendon, patient age, leg length, and vascular supply may also play a role. Although identifying and treating these factors have been the mainstay of treatment over the years, evidence on their effectiveness is lacking.5,12 Orthotics, such as inserts or a heel wedge, are sometimes used to help unload, reinforce, and protect the tendon.

Because many of the standard therapies for tendinopathy have failed to consistently correct the underlying degenerative process, many new treatments are being developed. These include extracorporeal shock wave therapy, radiofrequency ablation, percutaneous tenotomy, autologous blood or growth factor injection, prolotherapy, and topical nitrates. The effectiveness of these treatments is currently being investigated (Table 2).17–32

| Treatment | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Transcutaneous glyceryl trinitrate patches may decrease pain and improve healing in patients with tendinopathy.* | C | 17–19 |

| Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is a good treatment option for calcifying tendinopathy (shoulder) but is controversial in the treatment of noncalcifying tendinopathy.† | C | 20–22 |

| Ablation of neovascularization with sclerosing agents (sclerotherapy) is a promising treatment to improve tendon healing. | C | 23–25 |

| Autologous blood injection may improve pain in patients with tendinopathy. | C | 26–29 |

| Adding exogenous growth factors to an injured tendon may enhance healing. | C | 30–32 |

Surgery should be considered only if a comprehensive, nonsurgical treatment program of three to six months has failed; if the patient is unwilling to alter his or her level of physical activity; or if rupture of the tendon is evident. Surgery involves excising the abnormal tendon and releasing areas of scarring and fibrosis.

Specific Foot and Ankle Tendinopathies

POSTERIOR TIBIAL TENDON

The posterior tibial tendon performs plantar flexion, inversion of the foot, and stabilization of the medial longitudinal arch. Injury to this tendon can elongate the hind- and midfoot ligaments, especially the spring (calcaneonavicular) ligament, resulting in a painful flat-footed deformity. In severe cases, the deltoid ligament can become elongated, causing medial ankle instability.

The patient with posterior tibial tendinopathy usually cannot recall previous acute trauma, and the condition is commonly misdiagnosed as a medial ankle sprain. The majority of these patients have a history of an antecedent event causing tenosynovitis of the tendon, usually from twisting the foot, stepping in a hole, or slipping off a curb. Women are more commonly affected than men, and patients are often older than 40 years.33–35 The foot deformity from posterior tibial tendinopathy gradually increases from months to years and, with progression, causes pain along the lateral tarsal region (sinus tarsi). Without proper treatment, there is progression in stages leading to deformity, with degeneration of the tendon eventually leading to rupture. Treatment of posterior tibial tendinopathy is ultimately based on the severity of the injury and is broken down into stages3,33,36–38 (Table 3).

| Stage | Diagnostic features | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pain and swelling of tendon, able to perform single-leg heel raise, no foot deformity | Relative rest, pain medication, consider walking cast or orthosis |

| 2 | Pain and swelling of tendon, unable to perform single-leg heel raise, pes planus, midfoot abduction, subtalar joint is flexible | All stage 1 treatments, consider ankle-foot orthosis, referral to sports medicine specialist or orthopedic surgeon |

| 3 | All stage 2 features, subtalar joint is fixed, arthritis | Referral to orthopedic surgeon, all stage 2 treatments |

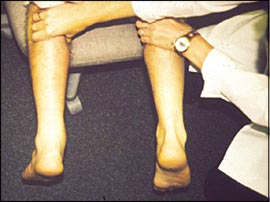

A common examination finding is the too many toes sign. When viewing the foot from behind, the examiner will see more toes exposed on the lateral aspect of the involved foot, along with flattening of the arch. Excessive pronation of the injured foot is also seen, with relative weakness of the posterior tibial tendon compared with the other foot. Normal heel varus (Online Figure A) is usually lacking when the patient is asked to stand on tiptoe. A single-leg toe raise may reproduce pain, and the patient will be unable to do 10 successive toe raises. Inability to initiate and maintain plantar flexion with this maneuver or the presence of abnormal heel varus may indicate rupture of the posterior tibial tendon.36

Initial treatment is often immobilization in a short leg cast or cast boot for two to three weeks if there is pain with ambulation. Steroid injections into the synovial sheath of the posterior tibial tendon are associated with a high rate of rupture and, therefore, are not commonly used.37,38 If conservative management fails for up to three months or if stage 3 foot deformities are diagnosed, the patient should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon. Progressive deterioration and a nonfunctional tendon can result if treatment is not initiated promptly at any stage.

PERONEAL TENDON

Persistent lateral ankle swelling, popping, and retro-fibular pain often occur after this type of injury. A subjective feeling of ankle instability is common. A positive peroneal tunnel compression test is pain with active dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot against resistance along the posterior ridge of the fibula.38 If swelling and tenderness of the peroneal tendon are seen in the absence of increased activity or trauma, rheumatoid arthritis or a seronegative arthropathy should be considered.45 Subluxation and/or dislocation of the peroneal tendons should be referred to an orthopedist.

The os perineum (Online Figure B) syndrome is a spectrum of disorders causing plantar lateral foot pain. This can result from fracture of the os perineum, and rupture or entrapment of the peroneal longus tendon near the os perineum. Pain along the lateral foot can occur with a single heel raise or resisted plantar flexion of the great toe.46,47

Lateral heel wedges and ankle taping help unload stress on the peroneal tendon, but there is no evidence that they speed healing. Physical therapy involves ankle range-of-motion exercises, peroneal strengthening, proper warm-up, and proprioception. Indications for surgery include failure of conservative management, recurrent peroneal instability, and rupture of the peroneal tendon.

ACHILLES TENDON

Injury to the Achilles tendon spans a continuum from peritendinitis to tendinosis. The least vascular area (vascular watershed region) is 4 to 6 cm above the insertion into the calcaneus, which is the usual site of degeneration and rupture.13 Common causes include overtraining, overpronating the foot, having poor flexibility of the gastrocnemius-soleus muscles, exercising on uneven surfaces and wearing inappropriate shoes for the activity, malalignment of the lower extremity, direct trauma, and complications from fluoroquinolone therapy.48,49

If degeneration of the tendon has occurred, a thickened, nodular area will be palpable. Results of the Thompson test (Figure 2) are normal in patients with tendinitis or tendinosis.50 A complete rupture of the Achilles tendon should be suspected if there is a history of acute pain after a pop in the posterior aspect of the heel, and a gap can be palpated within the Achilles tendon with a positive result on the Thompson test. Differential diagnosis includes retrocalcaneal bursitis and inflammation of the superficial bursa of the Achilles tendon.

Patients should avoid exercising up or down hills, interval training, and impact activities. Nonimpact activities, such as swimming and cycling, should be considered. There is growing evidence that eccentric strength exercises for the calf can improve symptoms of Achilles tendinosis, may reduce degenerative changes, and should be initiated early in treatment.8,14–16 Physical therapy modalities including ultrasound treatments, ionto- and phonophoresis, firm heel lift (1/8 to 3/8 inch), and gastrocnemius-soleus complex-soleus stretching have been helpful.14,16 Steroid injections should be limited to the retrocalcaneal bursa; however, there is growing evidence that the use of steroids around the Achilles tendon increases the risk of rupture.51,52

FLEXOR HALLUCIS LONGUS TENDON

Flexor hallucis longus (FHL) injury is the most common lower extremity tendinitis in classical ballet dancers, but it is also seen in persons who participate in activities requiring frequent push-off maneuvers. Tendinitis of the ankle or foot in ballet dancers is almost always caused by the FHL because the dancer is en pointe and stresses this tendon.53,54 Chronic tendinopathy of the FHL leads to chronic pain, early arthritis, and fibrosis with decreased range of motion.53

Patients with FHL injury describe an insidious onset of pain along the posteromedial aspect of the ankle behind the malleolus or the medial aspect of the subtalar joint. When the foot is placed in plantar flexion and the patient is asked to flex the great toe against resistance, there is pain or crepitus along the FHL. Another useful clinical test is comparing the amount of passive extension of the first metatarsophalangeal joint with the foot and ankle in the neutral and plantar flexed positions. FHL injury should be suspected with little to no extension in the neutral position but normal passive extension with plantar flexion.

Prevention includes reducing turnout of the hip so the dancer is working directly over the foot; avoiding hard floors whenever possible; strengthening the body's core (i.e., balanced strength and development of the muscles that stabilize and move the trunk of the body—abdominal, back, and pelvic muscles); and using firm, well-fitted shoes. Dancers with relatively stiff feet may have an incorrect en pointe position, which can contribute to the problem. For prolonged tendinitis, two to three weeks of immobilization in a weight-bearing cast or walking boot are recommended.

ANTERIOR TIBIAL TENDON

The anterior tibial tendon is the main dorsiflexor of the foot, but it adducts and inverts the foot as well. Dysfunction or rupture of this tendon is uncommon and results in foot drop and a slapping gait.

Anterior tibial tendon injury typically occurs as a chronic overuse injury in patients older than 45 years.55,56 The anterior tibial tendon can also be injured in distance runners and soccer or football players who forcefully dorsiflex a plantar flexed foot against resistance, placing an eccentric stress on the tibialis anterior muscle. Such patients present with weakness during dorsiflexion of the foot and pain over the anterior aspect of the ankle. A mass in the anterior leg may be seen or palpated by the physician, especially with dorsiflexion. Patients usually report a transient twinge of pain in the anterior ankle with no swelling or discoloration. Ultimately, a painless, flat-footed, slapping gait may occur. Complete rupture of this tendon most commonly affects patients in their 50s and 60s and should be differentiated from lumbar radiculopathy, peroneal nerve palsy, and complications of diabetes or syphilis.

Treatment involves immobilization in a walking cast for three weeks, followed by an additional three weeks of the walking cast worn only during ambulation. Steroid injections into the tendon sheath also may help. If rupture of the tendon is suspected, orthopedic consultation is required.56