Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(12):1429-1434

Patient information: See related handout on hip impingement, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Femoroacetabular impingement, also known as hip impingement, is the abutment of the acetabular rim and the proximal femur. Hip impingement is increasingly recognized as a common etiology of hip pain in athletes, adolescents, and adults. It injures the labrum and articular cartilage, and can lead to osteoarthritis of the hip if left untreated. Patients with hip impingement often report anterolateral hip pain. Common aggravating activities include prolonged sitting, leaning forward, getting in or out of a car, and pivoting in sports. The use of flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the supine hip typically reproduces the pain. Radiography, magnetic resonance arthrography, and injection of local anesthetic into the hip joint confirm the diagnosis. Pain may improve with physical therapy. Treatment often requires arthroscopy, which typically allows patients to resume premorbid physical activities. An important goal of arthroscopy is preservation of the hip joint. Whether arthroscopic treatment prevents or delays osteoarthritis of the hip is unknown.

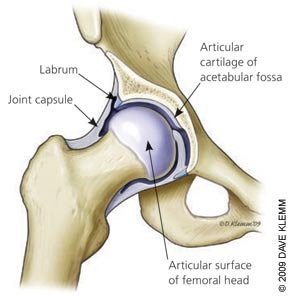

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint in which the articular surfaces of the femoral head and the acetabulum are lined with articular cartilage (Figure 1). The hip has a large range of motion in all planes, and is stabilized by a capsule, the surrounding muscles, and the labrum, which is a wedge-shaped cartilage structure that deepens the acetabulum and cushions the joint.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| The FADIR test is the most sensitive physical examination test for FAI. | C | 9 |

| Patients suspected of having FAI should have anteroposterior radiography of the pelvis and a modified Dunn view of the hip instead of standard hip radiography to assess for bony sources of impingement. | C | 11 |

| Patients whose history and examination are consistent with FAI should undergo magnetic resonance arthrography to evaluate for labrum and articular cartilage injury, and diagnostic injection of local anesthetic to confirm that the source of pain is intra-articular. | C | 13–16 |

| Patients with FAI pain refractory to conservative measures should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon for consideration of hip arthroscopy. | C | 1, 3, 17–19 |

The differential diagnosis of hip pain is broad and includes conditions of the hip, lower back, and pelvis (Table 1). In recent years, notable progress has been made in the diagnosis and treatment of nonarthritic hip injuries. Labral tears and early cartilage damage are now recognized as common sources of pain.2 Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is recognized as a common etiology of hip injury.3 Many joint-preserving operations, such as labral debridement, labral repair, and decompression of impinging bone lesions, are performed arthroscopically and have shown improvements in pain and function.4

| Condition | History | Signs | Tests | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avascular necrosis of the femoral head | Pain with insidious onset that is worse with weight bearing; recent trauma or corticosteroid use | Pain with all hip motions, antalgic gait | Radiography, MRI | Surgery or close observation by an orthopedic surgeon |

| Bursitis | Hip pain with exercise or direct pressure | Tender bursa over greater trochanter or iliopsoas tendon; may accompany intra-articular hip pathology | Usually none; MRI or ultrasonography can confirm | Physical therapy, corticosteroid injection; arthroscopic debridement if refractory |

| Cancer | Fever, night sweats, night pain, weight loss, history of cancer | Soft tissue mass near hip (e.g., sarcoma), pelvic mass, lumbar radiculopathy (if lumbar tumor) | Radiography, CT (hip, pelvis, or lumbar spine, depending on suspected location) | Radiation, chemotherapy, surgery |

| Hernia (inguinal, femoral) | Groin pain | Hernia palpated in inguinal or femoral canal | None | Surgery |

| Infectious arthritis of the hip | Severe pain with recent onset, difficulty moving the hip, recent surgery, intravenous drug use | Pain with hip motion, guarding | Radiography, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, joint aspiration | Joint aspiration and irrigation, antibiotics |

| Intra-articular loose bodies | Hip pain with exercise; recent trauma or overuse | Hip pain with log roll or Patrick (FABER) test | Radiography, magnetic resonance arthrography | Arthroscopy |

| Lumbar spine pathology (e.g., T12-L2 disk herniation, degenerative disease) | Pain with walking or prolonged sitting; possible numbness, tingling, or weakness in lower extremities | Limited lumbar motion; normal hip examination; sensory or motor abnormalities in lower extremities; positive straight leg raise (possibly) | Radiography, MRI | Physical therapy, analgesics, surgery |

| Muscle strain | Pain early in exercise, recent increase in exercise | Tender muscle, pain with stretching and with resistance of the affected muscle | None | Ice, rest, physical therapy |

| Osteoarthritis | Pain radiating to the groin, stiffness, age older than 40 years | Pain with hip rotation or Patrick (FABER) test, limited range of motion late in disease process | Radiography | Physical therapy, analgesics, surgical hip replacement or resurfacing if refractory |

| Pelvic pathology (e.g., endometriosis, ovarian mass, colon cancer) | Pain unrelated to position or activity | Tenderness or mass on pelvic examination | Ultrasonography, CT, endoscopy, or laparoscopy as indicated | Treat the cause |

Femoroacetabular Impingement

FAI is the abutment between the proximal femur and the rim of the acetabulum. It most often occurs anteriorly with flexion or rotation of the hip. FAI can begin in adolescence or adulthood. It usually progresses gradually and can injure the labrum and the articular cartilage of the hip, potentially limiting patients' ability to exercise and causing pain with daily activities.5 FAI is a common cause of labral injury, and FAI with or without labral injury has been identified as an early cause of hip osteoarthritis.3,5,6

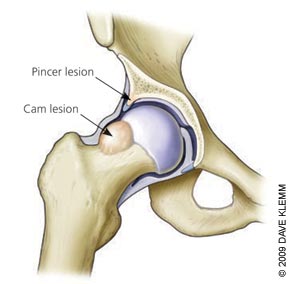

Some persons are predisposed to impingement by bony abnormalities, which can be congenital or developmental. Excessive overhang of the anterior acetabulum causes pincer impingement, which generally occurs during flexion or internal rotation (Figure 2). Exostosis or bony overgrowth of the femoral head and neck causes cam impingement.7 Although most persons with FAI have such bony abnormalities, some patients with normal radiography findings may have FAI and a labral tear.8

History

Patients with FAI typically have anterolateral hip pain. They often cup the anterolateral hip with the thumb and forefinger in the shape of a “C,” termed the C-sign9 (Figure 3). Pain is sharp when turning or pivoting, especially toward the affected side. It can worsen with prolonged sitting, rising from a seat, getting into or out of a car, or leaning forward. Pain is usually gradual and progressive.

Physical Examination

Physical examination of the hip begins with inspection, then palpation and assessment of range of motion. These steps and specific maneuvers for the hip are detailed in Table 2.9,10 The flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) test is the most sensitive physical examination test for FAI9 (Figure 4). Because some of the maneuvers can cause minor discomfort in persons without hip joint pathology, testing the uninvolved side for comparison is prudent.

| Examination component | Findings and interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inspection of hips | Asymmetry suggests SI joint dysfunction or leg-length discrepancy, either of which can cause SI joint pain, pubic symphysis pain, or muscle strain | ||

| Palpation of bone landmarks and muscles | Tenderness indicates that tissue is involved. Tenderness over the greater trochanter suggests trochanteric bursitis, which can coincide with intra-articular hip disorder; mass suggests tumor | ||

| Range of motion (flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation) | Assess for pain; localize pain | ||

| Pain in a stretched muscle indicates strain; pain in groin suggests intra-articular hip disorder; pain with slight motion is concerning for septic arthritis | |||

| Passive (examiner moves the hip) Active (patient moves) Resisted (examiner resists motion to test muscle strength) | Limitation of motion reflects severity of condition; pain helps to localize source of pain Weakness or pain in muscle suggests strain | ||

| Patrick (FABER) test | Groin pain indicates an iliopsoas strain or an intra-articular hip disorder; SI pain indicates SI joint disorder; posterior hip pain suggests posterior hip impingement | ||

| FADIR test | Reproducing the patient's anterolateral hip pain is consistent with FAI | ||

| Log roll (examiner rolls the supine leg back and forth) | Groin pain suggests an intra-articular disorder; posterior pain suggests posterior muscle strain | ||

| Patient hops on the involved leg | Pain can occur with strain, FAI, or other intra-articular disorder, but is concerning for hip stress fracture | ||

| Examination of lower back, abdomen, and pelvis | Certain conditions can refer pain to the hip; check for fever or tachycardia, which suggest septic arthritis | ||

Diagnostic Testing

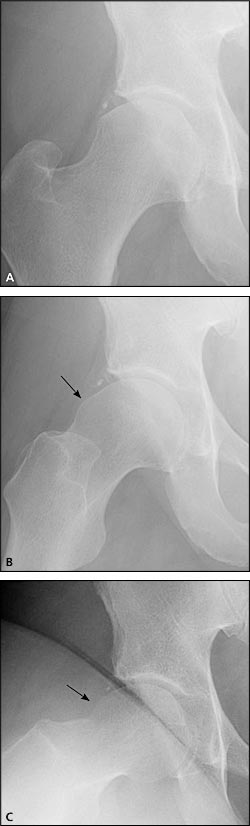

Radiography should be performed in patients in whom the history and physical examination are consistent with FAI. An anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis evaluates the hips for osteoarthritis; the acetabulum for dysplasia, overhang, or retroversion; the femoral head for osteonecrosis or remodeling; the sacroiliac joints for arthritis; and the lower lumbar spine. Because standard AP and lateral views of the hip can miss important abnormalities in patients with FAI, modified Dunn view radiography, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted 20 degrees (Figure 5), should be ordered.11 This view is highly sensitive for detecting cam lesions and osteophytes on the anterior femoral neck.11

If concern for FAI persists, magnetic resonance arthrography is recommended to evaluate the labrum. Magnetic resonance imaging without arthrography has limited sensitivity (25 to 30 percent) for labral tears; arthrography improves sensitivity to 90 to 92 percent.12,13 Arthrography is usually accompanied by a diagnostic injection of local anesthetic (e.g., 10 mL of bupivacaine [Marcaine]). The patient should keep a pain diary for four days after the injection; relief of pain confirms an intra-articular origin of pain. The physician should keep in mind, however, that labral tears can be asymptomatic.

One retrospective study found that intra-articular injection of the hip with bupivacaine during magnetic resonance arthrography has 92 percent sensitivity, 97 percent specificity, and 90 percent accuracy for diagnosis of an intra-articular disorder.14 The absence of pain relief with the injection suggests an extra-articular source of pain, which theoretically rules out FAI.15 However, the anesthetic will not relieve pain in some patients because contrast media can irritate the joint. In these patients, a separate diagnostic injection with bupivacaine can be done.

Management

There are no published studies of nonsurgical treatment of FAI. Because FAI is typically symptomatic with activities of daily living, recommending rest from exercise is not likely to be beneficial. Analgesics have a limited role, and a trial of physical therapy is prudent. Treatment goals are to improve hip muscle flexibility and strength, posture, and other muscle or joint deficits identified in the physical examination. Patients with refractory cases should be referred to an orthopedic sub-specialist for consideration of arthroscopy.

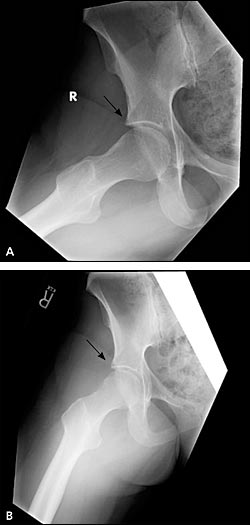

The goals of arthroscopy are to alleviate impingement, to repair or remove injured tissue, and to prevent or delay osteoarthritis. To alleviate impingement, pincer and cam lesions are removed and femoral offset is corrected, restoring bony alignment (Figure 6). Injured labral tissue is repaired or debrided. Studies of arthroscopic management of FAI are limited to case series. One study of 45 professional athletes undergoing arthroscopy for FAI showed that 42 (93 percent) returned to professional sports.16 A study of 100 patients with FAI yielded good or excellent results in 75 percent of patients at one year.17 Another study of 19 patients showed that 16 (84 percent) improved.18

Risks of surgery include neurovascular injury, infection, deep venous thrombosis, and heterotopic bone formation. Theoretic risks unique to arthroscopic treatment of FAI are femoral neck fracture and avascular necrosis of the femoral head, but few cases have been reported. It is hypothesized that arthroscopic treatment of FAI can prevent or delay the onset or progression of osteoarthritis of the hip, but this has yet to be demonstrated with long-term clinical follow-up.