Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):147-155

A more recent article on peripheral nerve entrapment and injury in the upper extremity is available.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Peripheral nerve injury of the upper extremity commonly occurs in patients who participate in recreational (e.g., sports) and occupational activities. Nerve injury should be considered when a patient experiences pain, weakness, or paresthesias in the absence of a known bone, soft tissue, or vascular injury. The onset of symptoms may be acute or insidious. Nerve injury may mimic other common musculoskeletal disorders. For example, aching lateral elbow pain may be a symptom of lateral epicondylitis or radial tunnel syndrome; patients who have shoulder pain and weakness with overhead elevation may have a rotator cuff tear or a suprascapular nerve injury; and pain in the forearm that worsens with repetitive pronation activities may be from carpal tunnel syndrome or pronator syndrome. Specific history features are important, such as the type of activity that aggravates symptoms and the temporal relation of symptoms to activity (e.g., is there pain in the shoulder and neck every time the patient is hammering a nail, or just when hammering nails overhead?). Plain radiography and magnetic resonance imaging are usually not necessary for initial evaluation of a suspected nerve injury. When pain or weakness is refractory to conservative therapy, further evaluation (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging, electrodiagnostic testing) or surgical referral should be considered. Recovery of nerve function is more likely with a mild injury and a shorter duration of compression. Recovery is faster if the repetitive activities that exacerbate the injury can be decreased or ceased. Initial treatment for many nerve injuries is nonsurgical.

Peripheral nerve injury in the upper extremity is common, and certain peripheral nerves are at an increased risk of injury because of their anatomic location. Risk factors include a superficial position, a long course through an area at high risk of trauma, and a narrow path through a bony canal. The anatomy and function of upper extremity nerve roots, as well as specific risk factors of injury, are described in Online Table A. The most common nerve entrapment injury is carpal tunnel syndrome, which has an estimated prevalence of 3 percent in the general population and 5 to 15 percent in the industrial setting.1 Given the potential for longstanding impairment associated with nerve injuries, it is important for the primary care physician to be familiar with their presentation, diagnosis, and management.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with a brachial plexus nerve injury (i.e., stinger) should undergo periodic reexamination for two weeks after the injury. Continued or new symptoms should be evaluated using neuroimaging and electrodiagnostics because a more severe nerve injury is likely. | C | 8–10 |

| For patients with a carpal tunnel syndrome diagnosis based on typical history and physical examination findings, electrodiagnostic testing does not usually change the diagnosis. | C | 24, 25 |

| Symptom relief from splinting, corticosteroid injections, and other conservative modalities for carpal tunnel syndrome have similar outcomes. Surgical intervention has been shown to have better outcomes than splinting. | B | 25, 29, 48 |

| Nerve | Anatomy | Function | Risk factors for injury | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axillary | From brachial plexus, around humeral head, through the quadrilateral space to deltoid/teres minor Quadrilateral space boundaries: humeral neck, teres major and minor, long head of triceps | Motor: deltoid, teres minor Sensory: skin over lower half of the deltoid | Humeral head compresses nerve during extreme abduction Upward pressure through the axilla Shoulder dislocation Compression in quadrilateral space | |

| Long thoracic | C5 to C7 merge, travel between clavicle and first rib through axilla to serratus anterior muscle Long nerve: 20 to 22 cm | Motor: serratus anterior Sensory: none | Sudden upper extremity traction Shoulder depression with contralateral neck flexion Prolonged compression (backpacker's palsy) | |

| Median | Brachial plexus down anterior arm, at antecubital fossa passes through radial tunnel, dives between two heads of pronator muscle, under flexor digitorum superficialis, through carpal tunnel | Motor: Injury at elbow or forearm: Weak wrist flexion, no interphalangeal flexion of thumb, index, and long digit Injury at wrist: none or weak thumb abduction Sensory: Injury at elbow: proximal forearm pain Injury at wrist: sensory loss in the thumb, radial 2.5 digits, and thenar eminence | Injury at elbow or forearm: radial tunnel, within pronator teres muscle, under flexor digitorum superficialis Injury at wrist: carpal tunnel syndrome | |

| Musculocutaneous | C5 to C7 merge into lateral cord brachial plexus, goes through axilla, under coracobrachialis, through biceps and under deep fascia at the elbow | Motor: Injury at shoulder: loss in biceps, coracobrachialis, and brachialis Injury at elbow: none Sensory: radial side of forearm (dorsal and volar), but not hand | Shoulder dislocation Hypertrophy of the coracobrachialis Deep brachial fascia of elbow as nerve exits biceps (sensory symptoms only) | |

| Radial | From brachial plexus, through axilla, down posterior arm until it circles toward anterior arm at spiral groove of the humerus; down anterior arm and enters radial tunnel just above the lateral epicondyle Divides into superficial and deep (posterior interosseus nerve) branches | Motor: Injury in axilla: loss of elbow flexion; weak wrist and digit extension; weak forearm supination Injury at elbow: superficial branch (radial tunnel): forearm pain, normal motor; posterior interosseus nerve: weak or no wrist extension Injury at wrist: no motor loss Sensory: variable sensory loss in distal forearm or hand Injury at elbow: no sensory loss; possible pain with repetitive forearm supination | Injury in axilla or proximal humerus (fracture) Injury at elbow: radial tunnel or area of proximal radius (fracture or dislocation); two nerve branches from elbow have injury potential, posterior interosseus nerve has mostly motor loss and the superficial branch has only sensory change (pain) | |

| Spinal accessory | Emerges through sternocleidomastoid muscle, across posterior neck, dives under trapezius | Motor: trapezius Sensory: none | Very superficial course in posterior neck and directly under the trapezius muscle | |

| Suprascapular | From upper trunk brachial plexus, through posterior triangle, across top of scapula and through scapular notch, down posterior aspect scapula and across scapular spine to supraspinatus, infraspinatus | Motor: supraspinatus, infraspinatus Sensory: acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints | Entrapment under transverse scapular ligament that covers the suprascapular notch Injury as it crosses scapular spine or under spinoglenoid ligament | |

| Ulnar | From brachial plexus down anterior arm; just above medial epicondyle it passes to the posterior compartment and into the cubital tunnel; down ulnar side of forearm into Guyon canal (boundaries are hamate and pisiform bones); splits into deep (motor) and superficial (sensory) branches in canal | Motor: no loss or weak thumb adduction, weak digit abduction, and adduction toward center of long digit Sensory: Injury at elbow: pain ulnar side of forearm with or without paresthesias in ulnar digits Injury at wrist: paresthesias in ulnar digits | Injury at elbow or forearm: cubital tunnel, ulnar nerve irritation with medial collateral ligament deficiency Injury at wrist: Guyon canal | |

| Upper trunk cervical plexus | Nerve roots C5 and C6 as they exit vertebral foramina and form upper trunk brachial plexus | Motor: infraspinatus, supraspinatus, biceps, and deltoid Sensory: C5 and C6 dermatomes | No protective coverings (epineurium and perineurium) on the nerves after they exit the foramina Increased risk of stretch injury at neck and shoulder regions Contusion or compression of upper trunk at Erb point | |

Pathophysiology

The three categories of nerve injuries are neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis. Neurapraxia is least severe and involves focal damage of the myelin fibers around the axon, with the axon and the connective tissue sheath remaining intact. Neurapraxia typically has a limited course (i.e., days to weeks). Axonotmesis is more severe, and involves injury to the axon itself. Regeneration of the nerve is possible, but typically prolonged (i.e., months), and patients often do not have complete recovery. Neurotmesis involves complete disruption of the axon, with little likelihood of normal regrowth or clinical recovery.2,3

Most nerve injuries result in neurapraxia or axonotmesis. Mechanisms of nerve injury include direct pressure, repetitive microtrauma, and stretch- or compression-induced ischemia. The degree of injury is related to the severity and extent (time) of compression.4

General Diagnostic Approach

Nerve injury should be considered when a patient reports pain, weakness, or paresthesias that are not related to a known bone, soft tissue, or vascular injury. Symptom onset may be insidious or acute. The location of symptoms, the type of symptom (i.e., paresthesias, pain, weakness), and any relation between a symptom and specific activity should be determined. Table 1 outlines the differential diagnosis of upper extremity nerve injury by symptom and area of the body.5,6

| Anatomic area | Symptom | Nerve injuries to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | Pain or numbness | Axillary |

| Brachial plexus | ||

| Weakness | Axillary | |

| Brachial plexus | ||

| Long thoracic | ||

| Spinal accessory | ||

| Suprascapular | ||

| Forearm | Pain or numbness | Pronator |

| Radial tunnel | ||

| Weakness | Posterior interosseous | |

| Hand | Pain or numbness | Radial at wrist |

| Ulnar at wrist or elbow | ||

| Weakness | Median at wrist | |

| Ulnar at elbow |

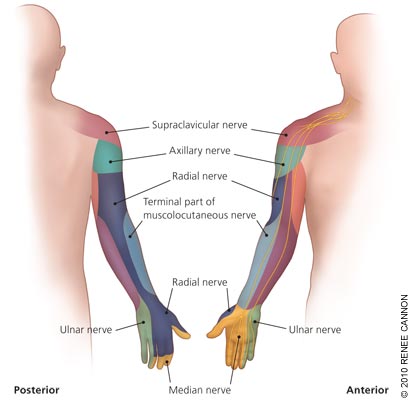

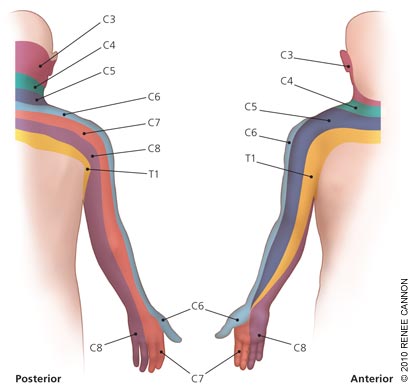

Initial physical examination of a patient with an upper extremity injury includes looking for the presence of a radial pulse, and sensation and movement in the digits. If there is no obvious neurovascular compromise, the remainder of the examination is based on the patient's history. The examination should follow the classic pattern of inspection, palpation, joint range of motion, muscle strength testing, and sensory and neurologic examination. It is helpful to understand the nerves commonly involved, their function, and the corresponding areas of the body at risk of compression or entrapment. Figures 1 and 2 show typical distributions of nerves in the upper extremity.7

Common Nerve Injuries and Entrapment Syndromes of the Upper Extremity

SHOULDER AND ARM

Axillary Nerve: Quadrilateral Space Syndrome. The axillary nerve is vulnerable to trauma as it passes through the quadrilateral space. Injury can occur from shoulder dislocation; upward pressure (e.g., from improper crutch use); repetitive overload activities (e.g., pitching a ball, swimming); and arthroscopy or rotator cuff repair. The typical symptom is arm fatigue with overhead activity or throwing. There may be associated paresthesias of the lateral and posterior upper arm. Examination reveals weak lateral abduction and external rotation of the arm.

Brachial Plexus Nerve: Stinger. A brachial plexus injury (i.e., stinger) is common in persons who play football, but it also occurs with other collision sports. The classic presentation is acute onset of paresthesias in the upper arm. A key characteristic is a circumferential rather than dermatomal pattern of paresthesias. Symptoms typically last seconds to minutes. Motor symptoms may be present initially or develop later.

A brachial plexus injury must be differentiated from a cervical spine injury. The initial examination should focus on the neck, with palpation of the cervical vertebrae to detect point tenderness and evaluation of neck range of motion. Any indication of a cervical spine injury mandates further emergent neurologic and radiologic evaluation. Point tenderness of the cervical vertebrae or pain with neck movement is a red flag for a cervical spine injury, in which case the patient should be immobilized. Bilateral symptoms or those involving upper and lower extremities are less likely to be from a brachial plexus injury.

If motor symptoms occur, the upper extremity muscle group exhibiting weakness correlates with the part of the brachial plexus that has been injured. Because motor symptoms may occur hours to days after the injury, repeated neurologic examinations are necessary—the patient should be reevaluated after 24 hours and then at least every few days for two weeks. If new symptoms or significant worsening of existing symptoms occurs, neuroimaging, electrodiagnostics, or surgical referral should be considered.8 Patients who have multiple occurrences of stingers should also have a more thorough workup, because they may have an underlying neck pathology that predisposes them to this injury.9,10

Occurrence during participation in a sporting event raises the issue of return to play. If all symptoms resolve within 15 minutes and there is no concern for cervical spine injury, the player may return to the same event with at least one repeat examination during that event.11

Long Thoracic Nerve. Injury to the long thoracic nerve occurs acutely from a blow to the shoulder, or with activities that involve chronic repetitive traction on the nerve (e.g., tennis, swimming, baseball). Presenting symptoms include diffuse shoulder or neck pain that worsens with overhead activities. Examination reveals scapular winging and weakness with forward elevation of the arm.

Spinal Accessory Nerve. Injury to the spinal accessory nerve can occur with trapezius trauma or shoulder dislocation. Radical neck dissection, carotid endarterectomy, and cervical node biopsy are iatrogenic sources of injury. Patients usually present with generalized shoulder pain and weakness. Examination of the shoulders reveals asymmetry. The affected side appears to sag and the patient is unable to shrug the shoulder toward the ear. Associated weakness of forward arm elevation above the horizontal plane is common. With chronic injury, the trapezius may atrophy.

Suprascapular Nerve. Injury to the suprascapular nerve is associated with repetitive overhead loading. The suprascapular nerve serves the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles. The infraspinatus may be the only muscle affected, depending on the site of injury. Loss of infraspinatus function presents as weak external rotation of the arm. Supraspinatus involvement additionally presents with weak arm elevation, which is most pronounced in the range of 90 to 180 degrees. Suprascapular nerve injury can result from other shoulder pathologies, specifically a glenoid labrum tear. Cyst formation at the suprascapular notch from a labral tear is not uncommon. The cyst compresses the suprascapular nerve, affecting the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.12 Suprascapular nerve injury and rotator cuff tear both lead to supraspinatus and infraspinatus weakness. Differentiating the two injuries may require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

| Component of evaluation | Evaluation area | Diagnoses to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Clavicle symmetry and integrity | Dislocation or fracture |

| Humeral head position | Shoulder dislocation; look for radial nerve injury | |

| Muscle deformity or atrophy | Muscle tear or chronic nerve injury | |

| Shoulder symmetry | Sagging shoulder suggests spinal accessory nerve injury | |

| Skin ecchymoses or swelling | Localized injury | |

| Palpation | Acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints | Dislocation |

| Clavicle, scapular spine | Fracture | |

| Muscle tenderness, integrity, or deformity | Contusion or muscle tear | |

| Range of motion* | Forward flexion 180 degrees; extension 45 degrees; lateral abduction 180 degrees; adduction 45 degrees; internal rotation 55 degrees; external rotation 40 degrees | If active range of motion is normal, no need to test passive range of motion; if active range of motion is abnormal and passive range of motion is normal, consider muscle or nerve injury; abnormal passive range of motion indicates joint pathology |

| Muscle strength | Adduction | Pectoralis and latissimus muscles |

| Extension | Posterior deltoid muscle, axillary nerve | |

| External rotation | Infraspinatus muscle, suprascapular nerve; teres minor muscle, axillary nerve | |

| Forward flexion | Anterior deltoid muscle, axillary nerve | |

| Internal rotation | Subscapular muscle and nerve | |

| Lateral abduction | Middle deltoid muscle, axillary nerve; supraspinatus muscle, suprascapular nerve | |

| Shoulder protraction (reaching); possibly winged scapula | Serratus anterior muscle, long thoracic nerve | |

| Shoulder shrug | Trapezius muscle, spinal accessory nerve | |

| Weakness in many movements of the shoulder or upper arm | Brachial plexus nerve injury | |

| Sensory/neurologic | Circumferential anesthesia or paresthesia | Brachial plexus nerve injury |

| Dermatomal anesthesia or paresthesia | Individual nerve root injury |

FOREARM AND ELBOW

Median Nerve at the Elbow: Pronator Syndrome. The pronator teres muscle in the forearm can compress the median nerve, which may cause symptoms that mimic carpal tunnel syndrome. Symptoms are discomfort and aching in the forearm with activities requiring repetitive pronation of the forearm, especially with the elbow extended. Paresthesias in the thumb and first two digits may be present. Forearm sensation is normal, and sensation of the digits may also be normal. In pronator syndrome, there is sensory loss over the thenar eminence, which is not a finding of carpal tunnel syndrome. Results of the Tinel sign and Phalen maneuver at the wrist should be negative in patients with pronator syndrome.13

Radial Nerve at the Elbow: Radial Tunnel and Posterior Interosseous Nerve Syndromes. The radial nerve divides into a superficial branch (sensory only) and a deep branch (posterior interosseous nerve) at the lateral elbow. Forearm pain that is exacerbated by repetitive forearm pronation is the presenting symptom of radial tunnel syndrome, which involves injury to the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Symptoms of radial tunnel syndrome are almost identical to those of tennis elbow (i.e., lateral epicondylitis), and distinguishing the two can be difficult because physical examination maneuvers that aggravate radial tunnel syndrome may also be positive in patients with tennis elbow (e.g., supination against resistance with the elbow and wrist extended, and resisted extension of the middle finger).14 A differentiating factor is the point of maximal tenderness. In radial tunnel syndrome, this point is over the anterior radial neck; in tennis elbow, it is at the origin of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle.

The presence of any motor symptoms is more likely related to injury of the posterior interosseus nerve, which supplies the extensor muscles of the hand. Generalized hand weakness is the presenting symptom of posterior interosseus nerve syndrome. Examination reveals weakness of digit and wrist extension, although this is usually more prominent in the digits than in the wrist.

Ulnar Nerve at the Elbow: Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. The ulnar nerve at the elbow is very superficial and at risk of injury from acute contusion or chronic compression. Compression can be from an external or internal source. As the elbow flexes, the cubital tunnel volume decreases, causing internal compression. Cubital tunnel syndrome may cause paresthesias of the fourth and fifth digits. There may be elbow pain radiating to the hand, and symptoms may be worse with prolonged or repetitive elbow flexion. Paresthesias precede clinical examination findings of sensory loss. Weakness may occur, but is a late symptom. When present, motor findings are weak digit abduction, weak thumb abduction, and weak thumb-index finger pinch. Power grip is ultimately affected.

| Component of evaluation | Evaluation area | Diagnoses to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Carrying angle in full extension (men: 5 degrees, women: 15 degrees); compare with contralateral side | Decreased angle suggests supracondylar fracture; increased angle suggests lateral epicondylar fracture; consider possible ulnar nerve injury |

| Diffuse elbow joint swelling; joint held in flexion | Interarticular joint pathology | |

| Swelling over olecranon | Olecranon bursitis | |

| Palpation | Biceps muscle and tendon tenderness or deformity | Ruptured distal biceps muscle or tendon |

| Cubital fossa tenderness or swelling | Joint capsule strain or hyperextension injury; look for median and musculocutaneous nerve injury | |

| Epicondyles or distal humerus | Fracture | |

| Radial head | Fracture or dislocation; consider radial nerve injury | |

| Ulnar nerve in sulcus: tender or thickened area over nerve | Ulnar nerve injury or entrapment | |

| Wrist extensor tenderness | Radial tunnel syndrome or lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) | |

| Wrist flexor or pronator muscle group tenderness | Pronator syndrome or golfer's elbow | |

| Range of motion* | Flexion 135 degrees; extension 0 to 5 degrees; supination 90 degrees; pronation 90 degrees | If active range of motion is normal, no need to test passive range of motion; if active range of motion is abnormal and passive range of motion is normal, consider muscle or nerve injury; abnormal passive range of motion indicates joint pathology |

| Muscle strength | Extension | Triceps muscle, radial nerve |

| Flexion | Brachioradialis muscle, musculocutaneous nerve | |

| Pronation | Pronators, acute nerve irritation of branch median nerve | |

| Supination | Biceps muscle, musculocutaneous nerve | |

| Sensory/neurologic | Biceps DTR | Musculocutaneous nerve C5 |

| Brachioradialis DTR | Radial nerve C6 | |

| Triceps DTR | Radial nerve C7 |

HAND AND WRIST

Median Nerve at the Wrist: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common nerve entrapment injury.15 Early symptoms are paresthesias of the thumb, index digit, and long digit. Some patients also have forearm pain. The most helpful physical examination findings are hypalgesia (positive likelihood ratio of 3.1) and abnormality in a Katz hand diagram.16 Although commonly used in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome, Tinel sign and Phalen maneuver are less accurate.16 The sensory examination is normal initially, although late findings include sensory loss in the median nerve distribution, weak thumb abduction, and thenar atrophy. Electrodiagnostic testing can be useful and quantitates severity of entrapment, although false negatives and false positives may occur.16,17

Radial Nerve at the Wrist: Handcuff Neuropathy. The superficial branch of the radial nerve crosses the volar wrist on top of the flexor retinaculum of the carpal tunnel. It is vulnerable to compression by anything wound tightly around the wrist. Historically, this is an area easily injured by tight handcuffs, thus the name “handcuff neuropathy.” The injury leads to numbness on the back of the hand, mostly on the radial side. Examination may reveal decreased sensation to soft touch and pinprick over the dorsoradial hand, dorsal thumb, and index digit. Motor function is typically intact.

Ulnar Nerve at the Wrist: Cyclist's Palsy. Injury of the ulnar nerve at the wrist is common in cyclists because the ulnar nerve gets compressed against the handlebar during cycling, resulting in “cyclist's palsy.” This type of nerve injury occurs with other activities involving prolonged pressure on the volar wrist (e.g., jackhammer use). Symptoms are paresthesias in the fourth and fifth digits. Digit weakness is uncommon because the motor portion of the nerve at the wrist is less superficial. Unless the activity is prolonged or chronic, results of the sensory examination are normal and numbness will resolve within a few hours after stopping the activity.

| Component of evaluation | Evaluation area | Diagnoses to consider |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Bilateral symmetry of knuckles in clenched fist | Asymmetry suggests metacarpal fracture |

| Dorsal or volar wrist mass | Ganglion cyst | |

| Skin ecchymoses or swelling | Localized injury | |

| Symmetric bulk of thenar and hypothenar eminences | Thenar atrophy suggests chronic median nerve injury; hypothenar atrophy suggests chronic ulnar nerve injury | |

| Palpation | Anatomical snuff-box tenderness | Scaphoid bone fracture |

| Carpal tunnel (Tinel sign) | Median nerve injury | |

| Guyon canal (depression between hamate hook and pisiform), asymmetric or excessive tenderness | Ulnar nerve injury | |

| Range of motion | Symmetric flexion and extension of all digits | Inability to flex or extend individual digit suggests tendon injury or fracture |

| Muscle strength | Active wrist extension | Radial nerve injury |

| Active wrist flexion | Ulnar and/or median nerve injury | |

| Digit adduction or abduction | Ulnar nerve injury | |

| Pincer mechanism thumb and index digit | Ulnar nerve injury | |

| Sensory/neurologic | Phalen maneuver at wrist | Median nerve injury |

| Sensation lateral hand | Ulnar nerve injury | |

| Sensation of web space between thumb and index digit | Radial nerve injury |

Diagnostic Testing

IMAGING

Chronic nerve injury can lead to denervation changes in muscle. These changes may be visible on MRI as abnormal signal patterns. A normal MRI finding does not rule out nerve injury. Newer techniques, such as gadofluorine M–enhanced MRI, may ultimately be able to assess nerve regeneration.19 Ultrasonography is a less expensive modality to define anatomic entrapment, but its use is limited by lack of standardization of technique and interpretation.20

| Nerve | MRI usefulness | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Suprascapular nerve at scapula | Often useful | Useful for evaluation of suspected ganglion cyst; oblique coronal view for suprascapular notch, axial view for spinoglenoid notch; also evaluates for rotator cuff pathology |

| Axillary nerve in shoulder | Useful if diagnosis unclear or recovery not following expected clinical course | Useful for evaluation of suspected paralabral cyst or labral pathology; oblique sagittal view of shoulder shows nerve at inferior rim of the glenoid; MRI less useful for evaluation of quadrilateral space because it is a dynamic entity |

| Median nerve at wrist | Useful if diagnosis unclear or recovery not following expected clinical course | Axial images of carpal tunnel evaluates for hypertrophy of synovium, space-occupying lesions (ganglion cyst) |

| Radial nerve at elbow | Useful if diagnosis unclear or recovery not following expected clinical course | Axial images at elbow show mass effect from enlarged bicipitoradial bursa, hypertrophy of extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle, or vascular pathology |

| Ulnar nerve at elbow | Useful if diagnosis unclear or recovery not following expected clinical course | Axial images can evaluate the cubital tunnel for nerve subluxation, arcuate ligament pathology; may need views of elbow in flexion and extension if subluxation suspected |

| Long thoracic nerve | Occasionally useful | Imaging of nerve itself not usually useful, but can sometimes show denervation changes of supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles |

ELECTRODIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Electrodiagnostic testing consists of nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG). Nerve conduction studies assess the integrity of sensory and motor nerves. Areas of nerve injury or demyelination appear as slowing of conduction velocity along the nerve segment in question. EMG records the electrical activity of a muscle from a needle placed into the muscle, looking for signs of denervation.21,22 The combination of nerve conduction studies and EMG can help distinguish peripheral from central nerve injuries. Electrodiagnostic testing is commonly used to evaluate for carpal tunnel syndrome and cubital tunnel syndrome. Nerve conduction studies have been shown to confirm carpal tunnel syndrome with a sensitivity of 85 percent and a specificity of 95 percent.23 Nerve conduction studies also may help confirm the diagnosis in patients who have a history or physical examination findings that are atypical of carpal tunnel syndrome. For most patients who have a typical presentation, nerve conduction studies do not change the diagnosis or management.24,25

Treatment

The initial management of most nerve injuries is nonsurgical. The main components of treatment are relative rest and protection of the injured area. Anti-inflammatory medications are often added, although it is unknown if they aid healing. Mobility of associated joints should be maintained at full range of motion, and effort should be made to increase the strength of any supporting or accessory muscles. Specifics of conservative therapy and indications for surgical referral are shown in Table 6.13,15,25–46

Systematic reviews of carpal tunnel syndrome have found short-term benefit from local corticosteroid injection, splinting, oral corticosteroids, ultrasound, yoga, and carpal bone mobilization.29 Symptom relief from local injection has not been shown to last longer than one month, and there is no demonstrated benefit from a second injection.30 Clinical outcome from local corticosteroid injection is similar to that from splinting combined with anti-inflammatory medication.29 Vitamin B6, ergonomic keyboards, diuretics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have not been shown to be beneficial.29,30 Patient characteristics that predict a poor response to nonsurgical therapy include age older than 50 years, symptom duration longer than 10 months, history of trigger digit, constant paresthesias, and Phalen maneuver that is positive in less than 30 seconds.47 Surgical treatment likely has better outcomes than splinting, but it is unclear if surgical treatment is better than corticosteroid injection.48

| Nerve injury type | Conservative therapy | Therapy duration and considerations | Indications for surgery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axillary26–28 | Shoulder range-of-motion exercises, including posterior capsule stretching; avoid heavy lifting For injuries associated with specific activity, assess shoulder biomechanics for that activity | Consider baseline nerve conduction studies at one month, repeat at three months Conservative therapy for three to six months | Rare |

| Carpal tunnel15,25,29,30 | Activity modification, splints worn at night Consider one steroid injection Oral steroids, yoga, ultrasound, and carpal bone mobilization have short-term benefit | Consider nerve conduction studies if no improvement within four to six weeks | Common Consider surgery if nerve conduction studies show severe injury, thenar atrophy, motor weakness |

| Cubital tunnel31–33 | Pad external elbow against external compression; decrease repetitive elbow flexion Extension splint (70 degrees) worn at night | Conservative therapy only for sensory symptoms | Occasional Consider surgery for motor weakness that is moderate or that does not respond to conservative therapy after three months Poor surgical outcome for established intrinsic muscle atrophy |

| Interosseous nerve syndrome34,35 | Cock-up splint to assist weakened wrist muscles Avoid provocative activities Consider elbow immobilization | Three to six months | Consider surgery sooner if late presentation with severe weakness or atrophy, progressive weakness |

| Long thoracic36,37 | Shoulder range-of-motion exercises to prevent contracture Strengthen trapezius, rhomboids, and levator scapula (remaining scapular stabilizers) | Nine to 12 months is average recovery time; consider conservative treatment for up to 24 months | Rare |

| Pronator13,38,39 | Activity modification; consider single steroid injection Splinting with elbow at 90 degrees can be used, with monitoring for loss of range of motion at elbow | Three to six months | Occasional |

| Radial tunnel38,40,41 | Physical therapy for extensor-supinator muscle group Consider single corticosteroid injection | Three months of physical therapy before consideration of surgery (unless intractable pain) | Consider surgical decompression for intractable pain, although no available evidence from randomized controlled trials |

| Radial wrist39,42 | Eliminate external compression May consider single cortisone injection | Three months | Rare |

| Suprascapular43–45 | Physical therapy to maintain full shoulder range of motion and strengthen other shoulder (compensatory) muscles Avoid heavy lifting and repetitive overhead activities | Early magnetic resonance imaging (at one month) to rule out anatomic lesion (i.e., ganglion cyst) Conservative treatment for six to 12 months if no anatomic lesion | Rare unless labral ganglion cyst present Presence of cyst indicates early consideration for surgery |

| Ulnar wrist39,46 | Pad volar wrist area; activity modification Splint wrist in neutral position | Six months | Rare |