A more recent article on evaluation and management of dizziness is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(4):361-368

Patient information: See related handout on dizziness, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Dizziness accounts for an estimated 5 percent of primary care clinic visits. The patient history can generally classify dizziness into one of four categories: vertigo, disequilibrium, presyncope, or lightheadedness. The main causes of vertigo are benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, Meniere disease, vestibular neuritis, and labyrinthitis. Many medications can cause presyncope, and regimens should be assessed in patients with this type of dizziness. Parkinson disease and diabetic neuropathy should be considered with the diagnosis of disequilibrium. Psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and hyperventilation syndrome, can cause vague lightheadedness. The differential diagnosis of dizziness can be narrowed with easy-to-perform physical examination tests, including evaluation for nystagmus, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver, and orthostatic blood pressure testing. Laboratory testing and radiography play little role in diagnosis. A final diagnosis is not obtained in about 20 percent of cases. Treatment of vertigo includes the Epley maneuver (canalith repositioning) and vestibular rehabilitation for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, intratympanic dexamethasone or gentamicin for Meniere disease, and steroids for vestibular neuritis. Orthostatic hypotension that causes presyncope can be treated with alpha agonists, mineralocorticoids, or lifestyle changes. Disequilibrium and lightheadedness can be alleviated by treating the underlying cause.

Diagnosing the cause of dizziness can be difficult because symptoms are often nonspecific and the differential diagnosis is broad. However, a few simple questions and physical examination tests can help narrow the possible diagnoses. It is estimated that primary care physicians care for more than one half of all patients who present with dizziness. 1 Dizziness is the chief presenting symptom in about 3 percent of primary care visits for patients 25 years and older, and in nearly 3 percent of all emergency department visits.2,3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| The Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed to diagnose BPPV. | C | 7, 9, 16 |

| Because they generally are not helpful diagnostically, laboratory testing and radiography are not routinely indicated in the work-up of patients with dizziness when no other neurologic abnormalities are present. | C | 7, 31, 32 |

| The Epley maneuver and vestibular rehabilitation are effective treatments for BPPV. | B | 40, 41, 42 |

Patient History

The initial description of dizziness can be difficult to obtain because patient responses are not always consistent.6 Therefore, the history should first focus on what type of sensation the patient is feeling. Table 1 includes descriptors for the main categories of dizziness.4,5,7,8 It is important to note that some causes of dizziness can be associated with more than one set of descriptors.

| Category | Description | Percentage of patients with dizziness |

|---|---|---|

| Vertigo | False sense of motion, possibly spinning sensation | 45 to 54 |

| Disequilibrium | Off-balance or wobbly | Up to 16 |

| Presyncope | Feeling of losing consciousness or blacking out | Up to 14 |

| Lightheadedness | Vague symptoms, possibly feeling disconnected with the environment | Approximately 10 |

A medication history should be obtained because dizziness (especially from orthostatic hypotension) is a well-known adverse effect of many drugs9 (Table 210,11 ). Patients should also be asked about caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol intake.9 Head trauma and whiplash injuries can cause a variety of dizziness symptoms, from vertigo to lightheadedness. The incidence of dizziness with a head injury or vertigo initially after whiplash have been reported as high as 78 to 80 percent.12 Selected causes of dizziness are summarized in Table 3.4,7,8,13–20

| Cardiac medications |

| Alpha blockers (e.g., doxazosin [Cardura], terazosin) |

| Alpha/beta blockers (e.g., carvedilol [Coreg], labetalol) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| Beta blockers |

| Clonidine (Catapres) |

| Dipyridamole (Persantine) |

| Diuretics (e.g., furosemide [Lasix]) |

| Hydralazine |

| Methyldopa |

| Nitrates (e.g., nitroglycerin paste, sublingual nitroglycerin) |

| Reserpine |

| Central nervous system medications |

| Antipsychotics (e.g., chlorpromazine, clozapine [Clozaril], thioridazine) |

| Opioids |

| Parkinsonian drugs (e.g., bromocriptine [Parlodel], levodopa/carbidopa [Sinemet]) |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants (e.g., baclofen [Lioresal], cyclobenzaprine [Flexeril], methocarbamol [Robaxin], tizanidine [Zanaflex]) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, doxepin, trazodone) |

| Urologic medications |

| Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil [Viagra]) |

| Urinary anticholinergics (e.g., oxybutynin [Ditropan]) |

| Cause | Category of dizziness | Pathophysiology | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | Vertigo | Loose otolith in semicircular canals causing a false sense of motion | Positive findings with Dix-Hallpike maneuver; episodic vertigo without hearing loss |

| Hyperventilation syndrome | Lightheadedness | Hyperventilation causing respiratory alkalosis; underlying anxiety may provoke the hyperventilation | Symptoms reproduced with voluntary hyperventilation |

| Meniere disease | Vertigo | Increased endolymphatic fluid in the inner ear | Episodic vertigo with hearing loss |

| Migrainous vertigo (vestibular migraine) | Vertigo | Uncertain; one hypothesis is that trigeminal nuclei stimulation causes nystagmus in persons with migraine | Episodic vertigo with signs of migraine, plus photophobia, phonophobia, or aura during at least two episodes of vertigo |

| Orthostatic hypotension | Presyncope | Drop in blood pressure on position change causing decreased blood flow to the brain, adverse effect of multiple medications (see Table 2) | Systolic blood pressure decrease of 20 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decrease of 10 mm Hg, or a pulse increase of 30 beats per minute |

| Parkinson disease | Disequilibrium | Dysfunction in gait causing imbalance and falls | Shuffling gait with reduced arm swing and possible hesitation |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Disequilibrium | Decreased tactile response when walking causes patient to be unaware when feet touch the ground, leading to imbalance and falls | Decreased sensation in lower extremities, particularly the feet |

VERTIGO

Otologic or vestibular causes of vertigo are the most common causes of dizziness,21,22 and include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular neuritis (viral infection of the vestibular nerve), labyrinthitis (infection of the labyrinthine organs), and Meniere disease (increased endolymphatic fluid in the inner ear).7,13 An estimated 35 percent of adults 40 years and older have vestibular dysfunction.14

Hearing loss and duration of symptoms help narrow the differential diagnosis further in patients with vertigo. Vertigo with hearing loss is usually caused by Meniere disease or labyrinthitis, whereas vertigo without hearing loss is more likely caused by BPPV or vestibular neuritis.8 Unilateral auditory symptoms help localize the cause to an anatomic abnormality, particularly in patients with peripheral disease.9 Episodic vertigo tends to be caused by BPPV or Meniere disease, whereas persistent vertigo can be caused by vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis.8

Migrainous vertigo, or vestibular migraine, is another underlying cause of vertigo that affects about 3 percent of the general population and about 10 percent of persons with migraine.15 This diagnosis should be considered after other causes of vertigo have been ruled out. Diagnosis of migrainous vertigo is established in patients with a history of episodic vertigo with a current migraine or history of migraine and one of the following symptoms during at least two episodes of vertigo: migraine headache, photophobia, phonophobia, or aura.15

PRESYNCOPE

Cardiovascular causes of dizziness include arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, carotid artery stenosis, and ortho-static hypotension.21 Of patients with supraventricular tachycardia, 75 percent experience dizziness and about 30 percent experience syncope.23 Symptoms brought on by postural changes suggest a diagnosis of orthostatic hypotension.9 A variety of cardiovascular medications increase the risk of orthostatic hypotension in older persons, including reserpine (at doses greater than 0.25 mg), doxazosin (Cardura), and clonidine (Catapres).24

DISEQUILIBRIUM

There are many underlying conditions that may cause a sense of imbalance. Stroke is an important and life-threatening cause of dizziness that needs to be ruled out when the dizziness is associated with other symptoms of stroke. However, other neurologic findings are generally present. In a population-based study of more than 1,600 patients, 3.2 percent of those presenting to an emergency department with dizziness were diagnosed with a stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), but only 0.7 percent presenting with isolated dizziness were diagnosed with stroke or TIA.25

Poor vision commonly accompanies a feeling of imbalance,16 leading to falls. The physician should inquire about a history of other problems that may cause imbalance, such as Parkinson disease, peripheral neuropathy, and any musculoskeletal disorders that may affect gait.17 Use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants increase the risk of ataxia and falls in older persons.24

LIGHTHEADEDNESS

Psychiatric causes of lightheadedness are common, particularly anxiety; therefore, questions about anxiety and depression should be included in the patient history. In one study, about 28 percent of patients with dizziness reported symptoms of at least one anxiety disorder.26 In another study, one in four patients with dizziness met criteria for panic disorder.27 A study of patients with chronic dizziness showed that those with panic disorder were more likely to have neurotologic findings than those without panic disorder.28 Up to 60 percent of patients with chronic subjective dizziness have been reported to have an anxiety disorder.29 Depression and alcohol intoxication have also been found to overlap with dizziness.21,30

Hyperventilation syndrome is an important cause of lightheadedness. Although the condition can be associated with anxiety disorders, many patients without anxiety experience hyperventilation. Hyperventilation is defined as breathing in excess of metabolic requirements, causing a respiratory alkalosis and lightheadedness. Patients may sigh repeatedly and may have associated symptoms, such as chest pain, paraesthesias, bloating, and epigastric pain.18

Physical Examination

The main goal of the physical examination is to reproduce the patient's dizziness in the office. There are a few simple physical examination tests that can be performed to aid in this goal.

First, blood pressure should be measured while the patient is in a supine position and again at least one minute after the patient stands. A systolic blood pressure decrease of 20 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decrease of 10 mm Hg, or pulse increase of 30 beats per minute is indicative of orthostatic hypotension.16,19

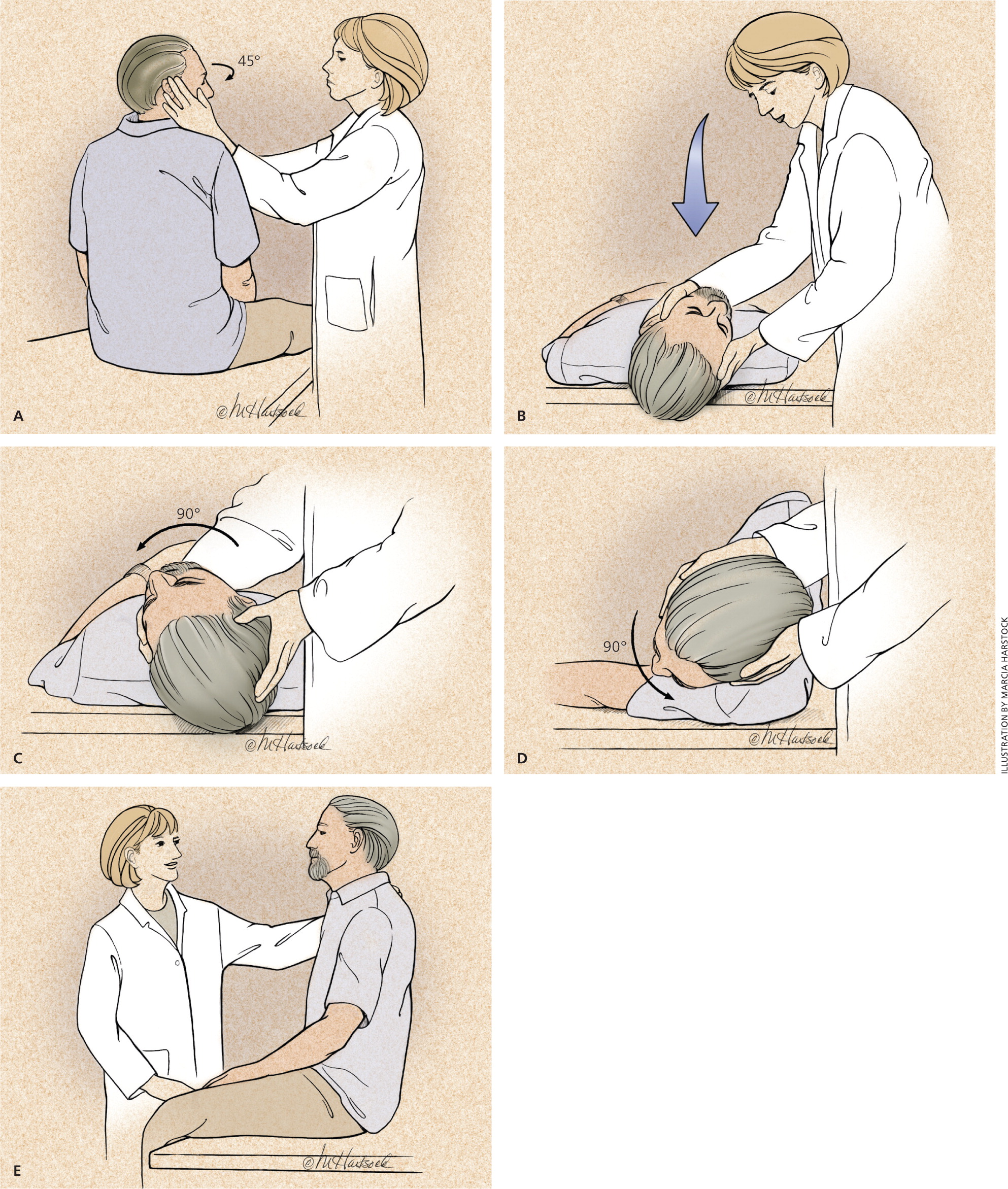

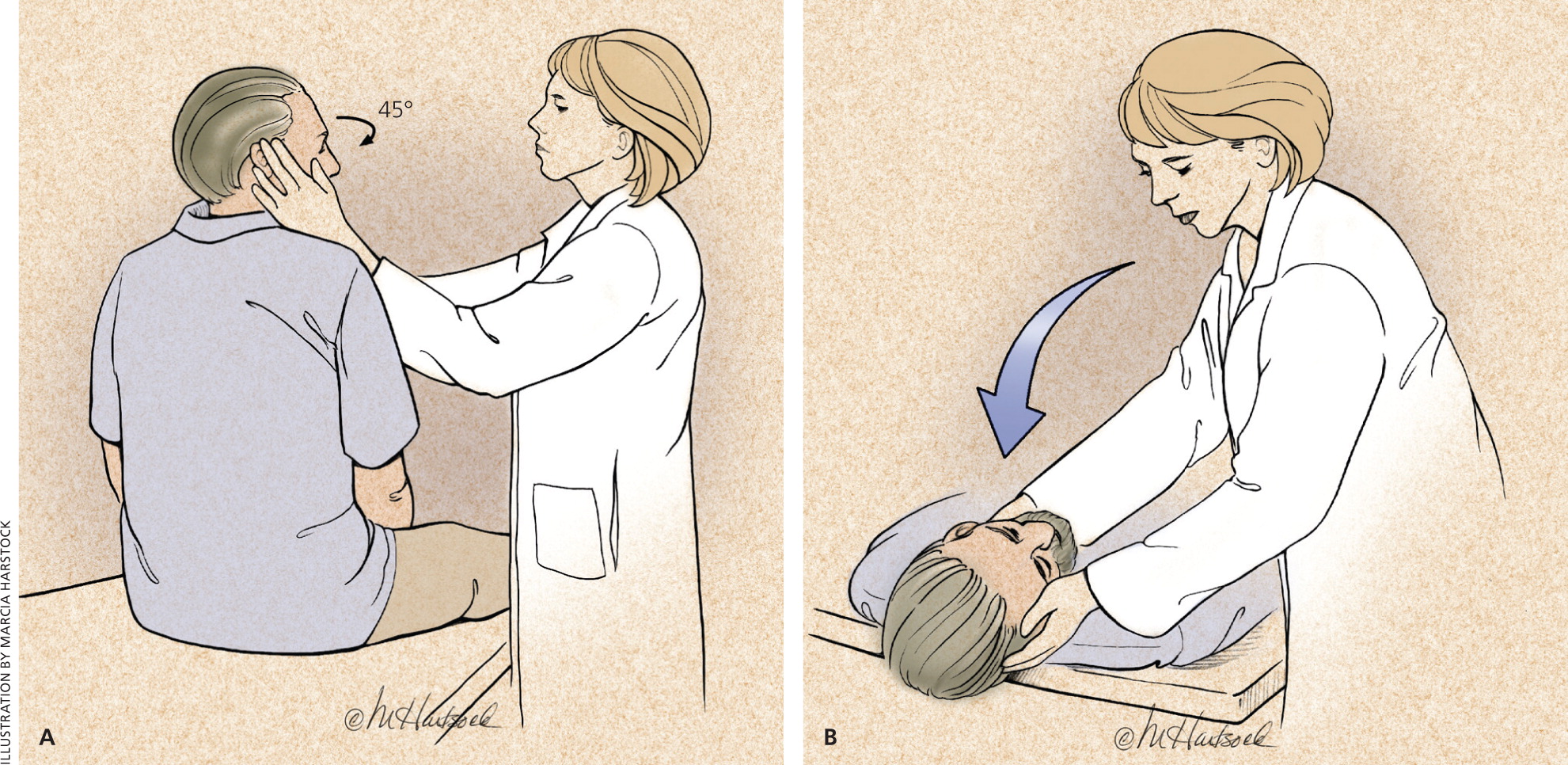

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver (Figure 19,16 ) is diagnostic for BPPV if positive, but does not rule it out if negative. The maneuver is performed on a flat examination table. While the patient is in a seated position, the physician turns the patient's head 45 degrees to one side, then rapidly lays the patient into a supine position with the head hanging about 20 degrees over the end of the table and observes the patient's eyes for approximately 30 seconds. The maneuver is repeated with the head turned to the opposite side. Nystagmus is diagnostic of vestibular debris in the ear that is facing down, closest to the examination table. There is usually a latent period of a few seconds before the patient develops nystagmus, and a sensation of vertigo for up to one minute.9,16 The sensitivity of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver is 50 to 88 percent for BPPV.7

Lesions of the labyrinth and cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear) commonly produce spontaneous nystagmus. Saccadic eye movements associated with a patient's smooth ocular pursuit of the physician's finger as it moves slowly left, right, up, and down may be associated with a central cause, such as brainstem or cerebellar disease. The head impulse test involves asking the patient to remain focused on a target while the physician moves the patient's head back and forth rapidly. Eye movement to one side with a refixation saccade (rapid oscillatory eye movement that occurs as the eye fixes on an object) is indicative of a lesion on the side to which the eyes move. Bilateral refixation movements commonly occur with ototoxicity. Another test that can elicit nystagmus involves the patient leaning forward 30 degrees while the physician shakes the patient's head back and forth vigorously for 20 seconds. The presence of nystagmus indicates a peripheral cause in the ipsilateral direction of the nystagmus.9

Other physical examination tests include the Romberg test and observation of gait. Swaying toward one side with the Romberg test is indicative of vestibular dysfunction in the ipsilateral side. Also, a patient's gait will lean toward the side of a vestibular lesion. Ataxia is indicative of cerebellar dysfunction, and the patient's gait is usually slow, wide-based, and irregular.9,20 Observation of gait is also important to detect symptoms suggestive of parkinsonism in patients presenting with disequilibrium.4 In early Parkinson disease, gait is usually slower with smaller steps and reduced arm swing, and progresses to freezing and hesitation in later stages of the disease.20 Screening for peripheral neuropathy is also important in patients presenting with disequilibrium.4

A thorough cardiovascular examination should be performed in all patients with dizziness. However, tests such as electrocardiography, Holter monitor testing, and carotid Doppler testing should be performed only if an underlying cardiac cause is suspected based on other findings or known cardiac disease.7

Additional Testing

In general, laboratory testing and radiography are not beneficial in the work-up of patients with dizziness when no other neurologic abnormalities are present.31,32 Laboratory studies, including complete blood count, metabolic panels, and thyroid function tests, have very low yield in diagnosing a cause of dizziness. In one meta-analysis, only 26 of 4,538 patients (0.6 percent) had laboratory abnormalities that explained their dizziness.7

Electronystagmography tests vestibular function by using electrodes to detect nystagmus. The test has a reported sensitivity of 69 to 74 percent and specificity of 81 to 83 percent for peripheral vestibular disorders. For central vestibular disorders, sensitivity has been reported as high as 81 percent and specificity as high as 93 percent.7

Approach to the Patient

After obtaining the patient history, the physician can tailor the physical examination to best fit the differential diagnosis. One approach to the initial evaluation of patients with dizziness is presented in Figure 2.

The initial history can help place the diagnosis into one of the four major categories of dizziness. Then, questions specific to that category can further narrow the possible diagnoses. A thorough neurologic and cardiovascular examination should be performed in all patients, as well as targeted components of the physical examination based on suspicion of the underlying diagnosis. Further testing, such as cardiac and radiologic testing, is only needed when specific causes are suspected.

| Cause | Treatment | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Vertigo | ||

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | Meclizine (Antivert), 25 to 50 mg orally every four to six hours | Commonly used to reduce symptoms of acute episodes of vertigo, although there are no RCTs to support its use; use of vestibular suppressants can lead to brainstem compensation and prolong vertiginous symptoms |

| Epley maneuver (canalith repositioning; see Figure 3) | Main benign paroxysmal positional vertigo treatment; safe and effective compared with placebo; video demonstration is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqokxZRbJfw&NR=1 | |

| Vestibular rehabilitation | Series of head and neck exercises that can be performed daily at home; video demonstration available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhinu_oU_hM | |

| Evidence for balance therapy (e.g., tai chi, Wii Fit) is accumulating | ||

| Meniere disease | Salt restriction (less than 1 to 2 g of sodium per day) and/or diuretics (most commonly, hydrochlorothiazide/triamterene [Dyazide]) | No large-scale RCTs to support these therapies |

| Intratympanic dexamethasone or gentamicin | Referral to an otolaryngologist required; in one small study, dexamethasone resolved symptoms in 82 percent of patients; in a larger study, gentamicin resolved symptoms in 80.7 percent of patients46,47 | |

| Endolymphatic sac surgery | Referral to an otolaryngologist required | |

| Vestibular neuritis | Methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrol), initially 100 mg orally daily then tapered to 10 mg orally daily over three weeks | In an RCT, methylprednisolone was more effective in improving peripheral vestibular function than valacyclovir (Valtrex) in patients with vestibular neuritis49 |

| Migrainous vertigo | Migraine prophylaxis with serotonin 5-HT1 receptor agonists (triptans) | Treatment based on expert opinion, not RCTs |

| Presyncope | ||

| Orthostatic hypotension | Review medication regimen | This is the first step, especially in older patients; rehydration (even increased water intake) can improve symptoms, especially in those with autonomic failure |

| Midodrine (Proamatine) titrated up to 10 mg orally three times daily | Alpha-1 agonist metabolite; to avoid supine hypertension, the third dose should be given by 6 p.m.; should be used only in severely impaired patients; in placebo-controlled trials, midodrine was associated with increased standing blood pressures and fewer orthostatic symptoms compared with placebo36 | |

| Fludrocortisone, initially 0.1 mg orally daily, titrated up weekly until peripheral edema develops or to a maximal dosage | Mineralocorticoids, such as fludrocortisone, are used to increase sodium and water retention; monitor blood pressure, potassium level, and for symptoms of heart failure | |

| Fludrocortisone and midodrine can be used in combination if either agent alone fails to control symptoms | ||

| Pseudoephedrine, 30 to 60 mg orally daily Paroxetine (Paxil), 20 mg orally daily | These drugs are options when midodrine and fludrocortisone are ineffective | |

| Desmopressin (DDAVP), 5 to 40 mcg intranasally daily | Nondrug therapy includes replacement of fluids, rising slowly from lying or sitting positions, sleeping with the head of the bed elevated, increasing salt intake, and regular exercise | |

| Disequilibrium | Treatment of underlying cause (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, Parkinson disease) | Because disequilibrium is generally a symptom of an underlying condition, treatment of the condition improves symptoms of disequilibrium |

| Lightheadedness | ||

| Hyperventilation syndrome | Breathing control exercises, rebreathing into a small paper bag | Reverses hypocapnia-related symptoms |

| Beta blockers | Treats associated symptoms, such as palpitations and sweating; not for use in patients with asthma | |

| Antianxiety agents (e.g., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) or short-term use of benzodiazepines | For use in patients with underlying anxiety | |