A more recent article on psoriasis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(9):626-633

Patient information: See related handout on psoriasis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that is often associated with systemic manifestations. It affects about 2 percent of U.S. adults, and can significantly impact quality of life. The etiology includes genetic and environmental factors. Diagnosis is based on the typical erythematous, scaly skin lesions, often with additional manifestations in the nails and joints. Plaque psoriasis is the most common form. Atypical forms include guttate, pustular, erythrodermic, and inverse psoriasis. Psoriasis is associated with several comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, lymphoma, and depression. Topical therapies such as corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, and tazarotene are useful for treating mild to moderate psoriasis. More severe psoriasis may be treated with phototherapy, or may require systemic therapy. Biologic therapies, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, can be effective for severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, but have significant adverse effect profiles and require regular monitoring. Management of psoriasis must be individualized and may involve combinations of different medications and phototherapy.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition that is often associated with systemic manifestations, especially arthritis. An estimated 2 percent of U.S. adults are affected, and the prevalence is about equal between men and women.1 Psoriasis can develop at any age, but onset is most likely between 15 and 30 years of age.1 The clinical course is unpredictable.2 Individualized and carefully monitored therapy can minimize morbidity and enhance quality of life.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians should evaluate patients with psoriasis for comorbidities, including psychological conditions. | C | 5 | Guideline based on randomized controlled trials |

| Topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, and tazarotene (Tazorac) are effective treatments for mild psoriasis. | A | 16 | Guideline based on randomized controlled trials |

| Systemic biologic therapies are effective treatments formoderate to severe psoriasis. | A | 4, 9 | Guidelines based on randomized controlled trials and expert reviews |

| Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors are effective treatmentsfor psoriatic arthritis. | A | 4, 9 | Guidelines based on randomized controlled trials |

Risk Factors and Etiology

Approximately one-third of patients with psoriasis have a first-degree relative with the condition. Research suggests a multifactorial mode of inheritance.2,3 Many stressful physiologic and psychological events and environmental factors are associated with the onset and worsening of the condition. Direct skin trauma can trigger psoriasis (Koebner phenomenon). Streptococcal throat infection may also trigger the condition or exacerbate existing psoriasis. Human immunodeficiency virus infection has not been shown to trigger psoriasis, but can exacerbate existing disease. As the infection progresses, psoriasis often worsens.1

Pathophysiology

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated disease with genetic predisposition, but no distinct immunogen has been identified. The presence of cytokines, dendritic cells, and T lymphocytes in psoriatic lesions has prompted the development of biologic therapies.6

Clinical Features and Classification

DERMATOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS

The diagnosis is usually clinical, based on the presence of typical erythematous scaly patches, papules, and plaques that are often pruritic and sometimes painful. Psoriasis occurs in several distinct clinical forms. Biopsy is rarely needed to confirm the diagnosis.

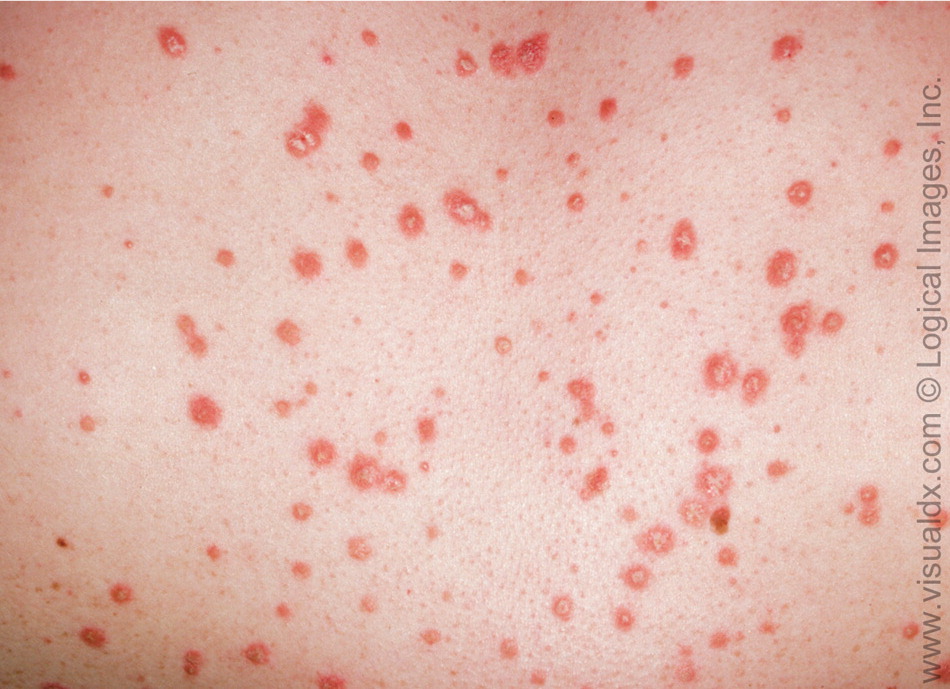

Guttate psoriasis is more common in patients younger than 30 years, and lesions are usually located on the trunk. It accounts for only 2 percent of psoriasis cases.4 Classical findings include 1- to 10-mm pink papules with fine scaling (Figure 5). Guttate psoriasis may present several weeks after group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal upper respiratory infection.7

NONDERMATOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS

Nail disease (psoriatic onychodystrophy) occurs in 80 to 90 percent of patients with psoriasis over the lifetime.8 Fingernails are more likely to be affected than toenails (50 versus 35 percent).4 Abnormal nail plate growth causes pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis (Figure 6).7 Psoriatic onychodystrophy is often resistant to treatment.4

Psoriatic arthritis is a seronegative inflammatory arthritis with various clinical presentations. It develops an average of 12 years after the onset of skin lesions.9 The prevalence ranges from 6 to 42 percent of patients with psoriasis, with men and women equally affected.9 The Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis are reported to have a specificity of 98.7 percent and sensitivity of 91.4 percent (Table 1).10 The severity of psoriatic arthritis is not related to the severity of skin disease.9

| Established inflammatory articular disease | ||

| plus | ||

| Score of 3 or more based on the following clinical findings: | ||

Psoriasis

| ||

Dactylitis

| ||

Comorbidities

MEDICAL CONDITIONS

Patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of a variety of medical conditions (Table 2).4,5 The association may be based on pathophysiology, shared risk factors, or even treatment for psoriasis. Social isolation may contribute to increased risk of certain medical conditions that are mediated by exercise and lifestyle factors, as well as to decreased quality of life.

| Comorbidity | Comments |

|---|---|

| Depression | Prevalence is up to 60 percent; may improve with treatment of psoriasis |

| Immune-mediated inflammatory conditions | Risk of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis is 3.8 to 7.5 times greater in persons with psoriasis; reported increased risk of psoriasis in persons with a family history of multiple sclerosis |

| Malignancy | Risk of lymphoma is increased 1.3- to 3.0-fold in persons with psoriasis; risk of squamous cell carcinoma is increased 14-fold in white patients after 250 or more psoralen plus ultraviolet A treatments |

| Metabolic syndrome, obesity | Increased prevalence in hospitalized patients with psoriasis |

| Myocardial infarction | Increased risk persists after controlling for major cardiovascular risk factors |

DISEASE IMPACT

Psoriasis causes significant social morbidity. In one survey, 79 percent of patients thought that psoriasis negatively affected their lives by causing problems with work, activities of daily living, and socialization.11 Three-fourths of these patients felt unattractive, and more than one-half were depressed. Increasing disease severity is associated with lower income, consulting multiple physicians, and reduced satisfaction with treatment. Younger and female patients are most affected by psoriasis.12,13 Quality-of-life scores tend to improve with age, suggesting that patients may adapt to the condition over time.13,14 One survey found that more than one-half of patients with severe psoriasis thought physicians could do more to help, and 78 percent reported frustration with the effectiveness of treatment.11 One study found that psoriasis caused a greater negative effect on quality of life than life-threatening chronic diseases.14

Treatment

Treatment goals include improvement of skin, nail, and joint lesions plus enhanced quality of life. Figure 7 provides a general approach to managing psoriasis; however, treatment must be individualized to incorporate patient preferences and the potential benefits and adverse effects of therapies. Consultation with a dermatologist may be warranted for patients with severe disease that requires systemic therapy.

MILD TO MODERATE DISEASE

Most patients with psoriasis have mild to moderate disease, affecting less than 5 percent of the body surface area and sparing the genitals, hands, feet, and face. These patients can often be treated successfully with topical therapies, including corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, tazarotene (Tazorac), and calcineurin inhibitors (Table 3).4,9,15–20 Less commonly used topical therapies include nonmedicated moisturizers, salicylic acid, coal tar, and anthralin.16

| Drug | Dosage | Monitoring | FDA pregnancy category | Comments | Estimated cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical therapies | |||||

| Corticosteroids | Once or twice daily to affected areas | — | C | Use with caution in children; limit duration of potent steroid use | — |

| Tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) | Twice daily to affected areas | — | C | Less effective for plaque psoriasis than facial or intertriginous psoriasis; approved for use in children older than two years; boxed warning about risk of malignancy with long-term use | $170 per 30-g tube |

| Tazarotene (Tazorac) | Once daily to affected areas | — | X | Perilesional adverse effects are common; approved for treatment of psoriasis in persons older than 18 years and for treatment of acne in persons older than 12 years | $225 per 30-g tube |

| Vitamin D analogs | Twice daily to affected areas | — | C | Appears safe for use in children; additional benefit if combined with topical corticosteroids; inactivated by ultraviolet A light | — |

| Systemic therapies | |||||

| Acitretin (Soriatane) | 10 to 50 mg orally per day | Renal function tests, LFTs, lipid panel, and CBC every one to two weeks until levels stabilize (typically four to eight weeks) | X | Often used at reduced doses with phototherapy | $770 to $1,900 per month, depending on dosage |

| Adalimumab (Humira)† | 80 mg subcutaneously on day 1, 40 mg one week later, then 40 mg every other week | LFTs, CBC‡ | B | Order baseline PPD tuberculin test; moderately painful injection site reactions may occur; live vaccines are contraindicated | $2,300 for two 40-mg/0.8-mL syringes |

| Cyclosporine (Sandimmune)† | 2.5 to 5.0 mg per kg per day, in two divided oral doses | Blood pressure; CBC; LFTs; lipid panel; and magnesium, uric acid, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and potassium levels every two weeks for the first three months of therapy, then monthly if stable | C | May be used continuously for one year; optimal use is intermittent (12 weeks for flare-up suppression); no data for treatment of psoriasis in children | $200 to 400 per month, depending on dosage |

| Etanercept (Enbrel)† | 50 mg subcutaneously twice per week for three months, then 50 mg once per week | LFTs, CBC‡ | B | Order baseline PPD tuberculin test; pruritic injection site reactions may occur; live vaccines are contraindicated; evaluated in children older than four years, but not approved by the FDA | $2,300 for four 50-mg syringes |

| Infliximab (Remicade)† | 5 mg per kg per dose infusion at weeks 0, 2, and 6, then every six to eight weeks | LFTs, CBC‡ | B | Order baseline PPD tuberculin test; live vaccines are contraindicated; infusion reactions are common and may be minimized with azathioprine (Imuran) or methotrexate | $3,200 for four 100-mg vials |

| Methotrexate† | 7.5 to 25 mg orally per week | LFTs, renal function tests, CBC, and platelet count every one to two months | X | Can be used long-term if patient has no signs of toxicity; supplement with folate | $8 to $30 per month, depending on dosage |

| Ustekinumab (Stelara)† | 45 mg in patients < 100 kg (222 lb) and 90 mg in patients 100 kg or more, given subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4, then every 12 weeks | — | B | Order baseline PPD tuberculin test; generally well tolerated | $6,300 for one 45-mg/0.5-mL syringe |

Topical corticosteroids are often used to treat psoriasis. No studies have directly compared individual topical corticosteroids, but systematic reviews concluded that more potent agents produce greater improvement in psoriasis symptoms.18 Local adverse effects are common and include skin atrophy, irritation, and impaired wound healing. Systemic effects may also occur, especially with extended courses of high-potency agents.17 Children are at increased risk of systemic effects because of their higher body surface area–to-weight ratio. Most treatment guidelines recommend gradually tapering topical corticosteroids after symptoms improve, but symptoms often return weeks to months after discontinuation. Many reports describe tachyphylaxis with topical corticosteroids. This may be genuine tolerance to treatment or the result of low adherence.16

The vitamin D analogs calcipotriene (Dovonex) and calcitriol (Vectical) are used as monotherapy or in combination with phototherapy to treat psoriasis in patients who have 5 to 20 percent body surface involvement. These agents have a slower onset of action but a longer disease-free interval than topical corticosteroids.16,21 Calcipotriene and calcitriol tend to be well tolerated. Serious adverse effects, such as hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone suppression, have been reported with supratherapeutic doses and in patients with renal insufficiency.17

Tazarotene is a teratogenic topical retinoid. Perilesional adverse effects (e.g., itching, burning) are common and can be managed with alternate-day application or use with topical corticosteroids and moisturizers. Tazarotene is as effective as topical corticosteroids in alleviating symptoms of psoriasis, but it is associated with a longer disease-free interval.16

The calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel) are approved for use in patients older than two years. In general, they improve symptoms with less skin atrophy than topical corticosteroids, and are considered first-line treatments for facial and flexural psoriasis. Although reports of adverse events are uncommon, these drugs carry a boxed warning for skin malignancy and lymphoma. Tacrolimus is superior to pimecrolimus in reducing psoriasis symptoms.16

SEVERE DISEASE

Patients with more severe psoriasis involving more than 5 percent of the body surface area or involving the hands, feet, face, or genitals are generally treated with phototherapy in combination with systemic therapies (Table 4).18 Systemic therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine (Sandimmune), acitretin (Soriatane), and biologic therapies. Second-tier agents with less supporting evidence include azathioprine (Imuran), hydroxyurea (Hydrea), sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), leflunomide (Arava), tacrolimus (Prograf), and thioguanine (Tabloid).22 Data do not support the use of systemic corticosteroids in patients with psoriasis.

| Spectrum or type of phototherapy | Combination therapy | Adverse effects | Additional information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excimer laser | None | Burning, erythema, hyperpigmentation | Adverse effects localized to treatment area | |

| Photochemotherapy (ultraviolet A phototherapy combined with methoxsalen) | Topical vitamin D analogs, topical retinoids, oral retinoids | Erythema, irregular pigmentation, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, xerosis | Erythema usually peaks in 48 to 96 hours | |

| Ultraviolet B | Topical vitamin D analogs, topical retinoids, oral retinoids, methotrexate, cyclosporine (Sandimmune), etanercept (Enbrel) | Burning, erythema, photoaging, pruritus | Available for home use | |

| Broad band (290 to 320 nm) | ||||

| Narrow band (311 nm) | ||||

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriatic disease for more than 50 years, but few well-designed clinical studies have evaluated its effectiveness. It is given weekly. Folate therapy may reduce adverse effects. Methotrexate has not been approved for use in children with psoriasis.22

Cyclosporine provides rapid alleviation of symptoms, but multiple adverse effects and drug interactions preclude long-term use. It is often used to suppress crises and as bridge therapy during initiation of slower-onset maintenance therapies. Cyclosporine is not approved for use in children.22

Acitretin is an oral retinoid with a slow onset of approximately three to six months. Acitretin is teratogenic, and adverse effects include mucocutaneous lesions, hyperlipidemia, and elevated liver enzyme levels. Acitretin is more effective when combined with phototherapy.22

Biologic therapy is increasingly used in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis and in psoriatic arthritis. The tumor necrosis factor inhibitors used in the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis include adalimumab (Humira), etanercept (Enbrel), and infliximab (Remicade). Etanercept is often used in conjunction with methotrexate. Of the biologic therapies, infliximab produces the most rapid clinical response. Clinical trialsof infliximab report sustained response and improvements in quality of life. Baseline and periodic monitoring are necessary for patients treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors because of the risk of serious infection, including tuberculosis. Safety data for the use of these drugs in patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis have been extrapolated from use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis (Table 5).4,9,17

Ustekinumab (Stelara) inhibits interleukins and is the newest agent for treatment of psoriasis. It was well tolerated in clinical trials, but data on long-term effectiveness and safety are limited.19

| Demyelinating disorders |

| Exacerbation of cardiac failure |

| Hepatic dysfunction |

| Infections, including tuberculosis* |

| Lupus-like syndrome |

| Risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer, lymphoma, and solid-organ cancer |

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms psoriasis, arthritis, etiology, and treatment. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and reviews. Also searched were the National Guideline Clearinghouse database, PubMed, Clinical Evidence, and UpToDate. Search dates: March 2011 and July 2012.